The James Bond Movie Moments That Defined 007

What are the key moments in the 007 franchise that have shaped our views of the films over the years?

There’s no question that the James Bond film franchise – the second longest-running such series in cinema history after Godzilla – comes with certain expectations in the minds of viewers. We can predict, mostly like clockwork, that 007 will wear a tux at some point in every film, he will bed at least one or more beautiful women, he’ll drive an Aston Martin (or some other high-end vehicle), and that he’ll have one polite conversation with the villain before the shooting really starts. There will also be a surreal, psychedelic credits sequence, often a big action scene before the credits, and so on.

But all those iconic trademarks of the Bond film franchise didn’t happen overnight. They were gradually introduced, especially in the early films, with some of them springing from the original Ian Fleming books and others invented by the filmmakers who adapted them. Some have remained virtually the same since their inception, while others – like Bond himself – have evolved over time.

Here is a look at the significant, if not crucial, moments in the history of the Bond movies that defined 007 and the series itself, from the initial casting of the British agent to his transformation in the 21st century (and just for the record, we’re focusing on the 25 official Bond films made by Eon Productions, not the two non-canon versions of Casino Royale or the series-adjacent Never Say Never Again).

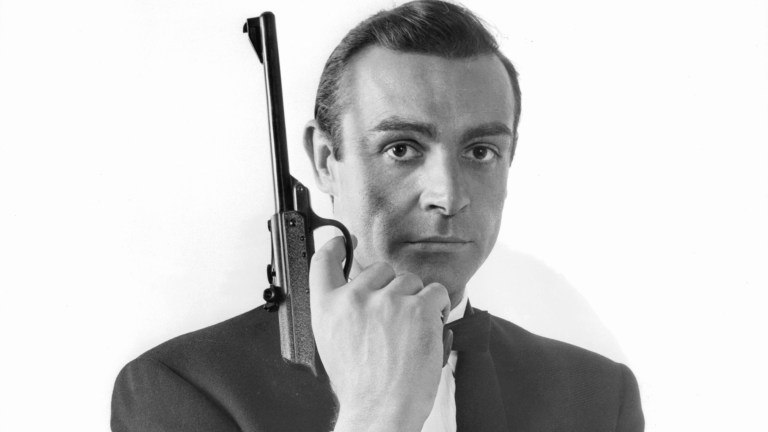

Casting Connery

From the moment you see him onscreen, you can’t take your eyes off him. Dark eyes blazing, cigarette tucked into his mouth, drink nearby and tux wrapped around his broad frame, Sean Connery uttered the famous words for the first time – “Bond, James Bond” – in 1962’s Dr. No and made you believe in an instant that he was Ian Fleming’s superspy, lifted right off the page.

While Connery became a bit jauntier in the role over the course of his term, he established the template for Bond right from the outset – which makes it strange to think that he was nobody’s initial idea to play the role. Richard Burton, Cary Grant, David Niven, and Patrick McGoohan were among the many names tossed around at the time, but hiring the relatively little-known Connery – who brought a tough masculinity and swagger to the role that truly defined 007 – was the first important step in creating a character and franchise for the ages.

The Bond Girl

We should probably call them “Bond women” now, and there is a lot of room right to the present day to debate how misogynist the early Bond films were – and how they’ve tried to evolve with the times with varying degrees of success – but there’s no question that when Ursula Andress walked out of the surf to proudly confront Bond as the bikini-clad, feral Honey Ryder in Dr. No, she set hearts racing around the world – and, like her leading man, established a template for all the Bond women that followed.

Technically, Eunice Gayson’s sexy Sylvia Trench was the first “Bond girl,” and their brief tête-à-tête at the beginning of the film also established 007’s casual attitude toward women and sex. But Honey was the model for the “main” Bond girl, whose presence in the plot can either be essential or there to simply complicate Bond’s mission, and who usually starts out strong-willed and independent but eventually (and often unfortunately) requires rescuing by our hero. Whatever the case, and however the series has evolved since, Andress and her character launched a long line of staggeringly beautiful co-stars who stay resolutely by Bond’s side and often end up in his bed – never to be seen again after the closing credits.

The Super-Villain

His casting would be considered wildly inappropriate now – actor Joseph Wiseman was Canadian-American, nowhere near Chinese-German like his character – but the title villain of Dr. No, like Bond and Honey Ryder, set the tone and flavor for most of the Bond super-villains to come.

Again, the “Yellow Peril” aspects of the character are cringeworthy now, along with the prosthetic makeup used to give Wiseman “Chinese” eyes. Most Bond villains since then have stayed away from such tropes, although at the time they were acceptable. But more importantly, Dr. Julius No was a brilliant megalomaniac with plans for world disruption or domination, vast resources at his disposal, a seemingly endless army of loyal henchmen, and the ability to strike sheer terror into the hearts of those who crossed him before he had them eliminated.

Bond has had one of the best rogues’ galleries in cinema history, with Auric Goldfinger, Ernst Blofeld, Francisco Scaramanga, Karl Stromberg, Hugo Drax, and Le Chiffre all contributing to the canon, but it all started on the screen with Dr. No.

The Pre-Titles Sequence

While Dr. No begins with the now-classic James Bond theme by Monty Norman (which of course became the defining musical cue of the series) and some rather non-descript credits before getting right into its story, 1963’s From Russia with Love launched a narrative concept that has remained part of the franchise ever since: the pre-titles sequence.

The scene always takes place after the gun-barrel opening and before the main credits roll, and can either be a throwaway sequence featuring Bond getting into some shenanigans that have no bearing on the rest of the film, or else a scene that’s crucial to the rest of the movie. The scope of the scenes has also changed over time, ranging from gasp-inducing action extravaganzas (the ski sequence in The Spy Who Loved Me) to small, yet sharp character moments (Bond earning his license to kill in a near-empty office in Casino Royale). Whatever form they take, they’ve been part of the franchise since Bond’s second screen outing, and we expect they’ll remain part of the series for as long as it continues.

The Title Credits and Theme

Right from the outset, the Bond films had quirky, surreal main title credits, and even on From Russia with Love the template of the credits playing against a backdrop of gyrating female flesh and shadowy acts of violence and gunplay began to crystallize. But it all came together for the first time in Goldfinger, where the semi-nude female figures, highly phallic weapons, and psychedelic colors merged into a seamless whole with the series’ first fully-sung theme song – in this case, “Goldfinger,” performed by an ear-shattering Shirley Bassey. Even if the overly sexualized imagery has been toned down over the years, the series has rarely strayed from this formula since – and yielded some classic tunes in the process.

The Guy Hamilton Factor

Goldfinger also brought about another important shift in the tone of the Bond film series, thanks largely in part to the influence of director Guy Hamilton. After Terence Young directed the first two films (returning for Thunderball), Hamilton steered 007 into a jokier, jauntier direction, while also introducing elements such as the seemingly indestructible henchman (Oddjob) and a flashier array of gadgets (such as Bond’s tricked-out Aston Martin), the latter all dutifully provided by the eternally exasperated Q (Desmond Llewelyn, making his second appearance but the one that really nailed down the character).

Hamilton later directed three more entries in the series, all among its spoofiest: Diamonds are Forever (1971), Live and Let Die (1973), and The Man with the Golden Gun (1974). But his influence would be felt across the series as a whole, especially combined with the lighter touch of Roger Moore as 007. It wouldn’t be until Timothy Dalton inherited the role that the 007 franchise tried a hard pivot back to the grittier nature of the original Fleming novels, with mixed results.

Recasting Bond

When Sean Connery first left the series following 1967’s You Only Live Twice, the idea of recasting James Bond seemed as unthinkable as the idea today of recasting Iron Man or Wolverine. But the prospect seemed inevitable, and the Bond producers first tried their luck by catapulting a complete unknown – a man with literally no acting experience except for a commercial – into the coveted role of 007.

That man was George Lazenby, and while his sole outing in the role, 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, is considered one of the series’ finest, it’s difficult to say how Lazenby would have fared had he stuck around for future installments. But while OHMSS was not as big a hit as the previous films in the series, it was (contrary to popular belief) not a bomb either – which meant that perhaps with the right face on the screen, Bond could be recast after all.

After the producers lured Connery back for Diamonds Are Forever, they went with the more established Roger Moore as Bond for the next seven films. His first two, Live and Let Die and The Man with the Golden Gun, were shaky at the box office, yet his third entry, 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me, found Moore not just settling into the role but making it his own. Its deft combination of humor, spectacle, and villainy, combined with Moore’s more lighthearted approach, made TSWLE a massive hit – and showed that audiences would accept different actors in the role – and have ever since.

‘A Sexist, Misogynist Dinosaur’

The Pierce Brosnan era of Bond films largely didn’t reinvent the wheel, choosing instead to reinforce what we liked about the character instead of pushing too hard in new directions. Brosnan, playing as sort of a hybrid of Moore and Dalton with an emphasis on Moore, did have his fans, and his first film in the role, 1995’s GoldenEye, has found its way into many fans’ top 10 lists. Among other things, GoldenEye is noteworthy for acknowledging – following a six-year absence from the screen during which the Berlin Wall fell and the Cold War all but ended – that the world around 007 was changing.

“I think you’re a sexist, misogynist dinosaur,” says a new, female M (Judi Dench) to a slightly flummoxed Bond in a brief but key scene early in the film. With the various menaces that Bond used to battle now fading into the past, and his “boyish charms” and wanton approach to women nowhere near as amusing as they used to be, GoldenEye let it be known that the franchise was willing to accept its past but move on from it. It’s done so with varying degrees of success ever since.

The Daniel Craig Century

Daniel Craig’s tenure as James Bond lasted for five films over 15 years, longer chronologically than any other actor. That’s due to various factors, including the length of time it now takes to develop blockbuster movies, a pandemic that put his last film, No Time to Die, on hold for two years, and Craig’s own indecision about returning to the part on at least two occasions. As a result, Craig’s Bond has come to define the character for nearly a generation of moviegoers. But is that good thing in the long run?

Craig’s era certainly returned Bond to his roots with the outstanding Casino Royale (2006), but succeeding outings, while rebuilding the 007 mythology from the ground up, also painted the character as more tormented and haunted by his past than any previous incarnation. Whereas Bond used to save the world regularly, the world in these films revolved around 007 himself, making every character part of both the tapestry of Bond’s soul and one big overarching narrative around that soul’s redemption.

Craig’s tenure was a mix of the great (Skyfall) and the bad (Quantum of Solace), but it provided a very different interpretation of the character for millions of viewers – many of whom were watching a 007 movie for perhaps the first time. Will his definition of Bond stand? Or will the next 007 – whoever that person may be – and the next set of films provide another new way for us to define James Bond, and what we expect from a Bond movie?

All we know for sure is that James Bond will return.