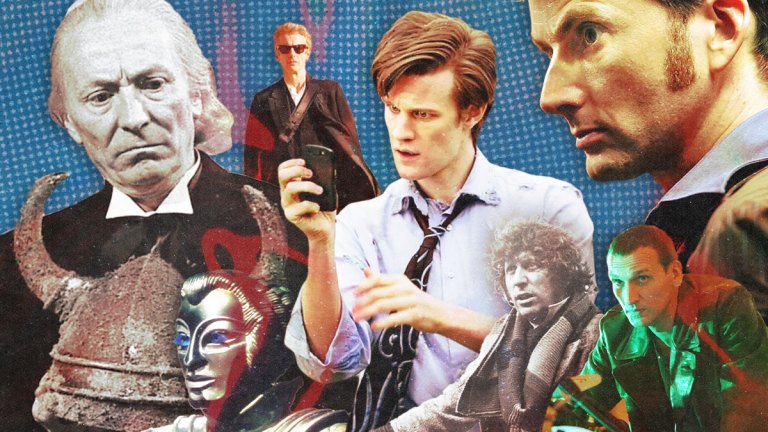

Doctor Who: The 60 Best Episodes

60 years. 60 brilliant episodes.

It’s Doctor Who’s 60th year, it’s a time of celebration, and sometimes we like to celebrate by getting granular. Any fool can write a Top 60 Stories list, we’re breaking it down further. The plan is be ranking single frames by 2063.

As it’s a time of celebration, we cordially invite you all to join in by listing your top 60 episodes in the comments. Eat some Celebrations. Play some Kool and the Gang. We can go back to complaining about Doctor Who later, for now let’s try to focus on this extraordinary children’s show featuring a genocidal maverick as its hero, and how mint it is. Because it is, really, I don’t think we mention that enough. This could actually be on telly in 2063.

Very scientific process behind this list: they’re the 60 best Doctor Who TV episodes, listed in chronological order.

1. An Unearthly Child – An Unearthly Child/Part One

(Season One, 1963, written by C.E. Webber and Anthony Coburn, directed by Waris Hussein)

As first episodes go, the one where the Doctor kidnaps some school teachers certainly clashes with the more vibrant optimistic tones of the brand nowadays, but Christopher Eccleston’s Ninth Doctor was pretty damn abrasive in ‘Rose’ too. Not quite hostile abduction abrasive, but difficult nonetheless. It works, though.

It’s always worth stating how aggressively unsettling Doctor Who has been. First of all, there’s the title sequence and theme music (What is this black and white swirling void? What is that noise? Is that music? Am I supposed to be this frightened? WHAT THE HELL IS THIS?) and then there’s the Doctor himself, shown here threatening his granddaughter and kidnapping two schoolteachers. The first episode finishes here with a police box seemingly escaping this Earth, tearing a hole in the fabric of reality (using the vortex effects from the title sequence), and then appearing leaning and incongruous in a desert landscape before a shadow shows us someone else has borne witness to this event. You’d be forgiven for being alarmed.

2. The Daleks – The Survivors/Part Two

(Season One, 1963, written by Terry Nation and directed by Christopher Barry and Richard Martin)

Landing on an unknown planet and unaware of the radiation levels, the Doctor takes Susan, Ian and Barbara to look at a vast metallic city. What could possibly go wrong?

They meet the Daleks, who temporarily paralyse Ian and imprison the travellers, taking a vital TARDIS component (which it turns out the Doctor sabotaged in order to force them to go to the city). And they’re dying of radiation sickness. That’s what could go wrong. All of which means Susan is about to embark on one of the most terrifying experiences of her life.

3. The Dalek Invasion of Earth – The Waking Ally/Part Five

(Season Two, 1964, written by Terry Nation and directed by Richard Martin)

The Daleks have conquered a future Earth, and the Doctor and his friends find themselves captured or part of a rebellion, heading for the Daleks’ mineworks in Bedfordshire to find out what their ultimate plan is.

The penultimate episode of this six-part story is one that plays to Terry Nation’s strengths – a grim war story where we see the human cost of the invasion: Barbara is betrayed to the Daleks in return for food, the man Ian is travelling with finds his robotised brother, and they end up killing each other. But there are also moments of light: Susan is falling in love, and once captured, Barbara uses her cunning to stay alive. Then there’s the reveal of the Dalek plan in all its gonzo pulpy glory.

4. The Rescue – Desperate Measures/Part Two

(Season Two, 1965, written by David Whitaker and directed by Christopher Barry)

A two-episode reset after ‘The Dalek Invasion of Earth’: ‘The Rescue’ introduces companion Vicki as a girl from the future who is stuck on the planet Dido with Bennett, an older man invalided after their spaceship crashed. Both are menaced by Koquillion, a bipedal creature with a face like an insectoid warthog. The Doctor, Ian and Barbara arrive and promise to help Vicki escape.

The second episode gives us plenty of twinkling wizardry from Hartnell as the Doctor calms and befriends the orphaned girl. You’ve got the alluring part of the character there – the cast’s family dynamic giving off real warmth. And then you’ve got the Doctor confronting Koquillion. A great shout if you’re intent on introducing someone to the show with a bit of Hartnell drama.

5. The Romans – The Slave Traders/Part One

(Season Two, 1965, written by Dennis Spooner and directed by Christopher Barry)

This is where approximately 90% of the Ian and Barbara companion shipping comes from.

For a brief moment before the slapstick and the carry-on farce ensues (or, in Ian’s case, the incredibly traumatising enslavement subplot) the TARDIS crew relax in an unoccupied villa, reclining in togas and necking amphoras of wine. Before the Doctor and Vicki succumb to their inevitable wanderlust, it’s lovely to see them all simply hanging out together.

6. The Space Museum – The Space Museum/Part One

(Season Two, 1965, written by Glyn Jones and directed by Mervin Pinfield)

The general consensus is that the first episode of ‘The Space Museum’ is great while the other three are a bit of a letdown. While this is slightly unfair (no episodes featuring Vicki instigating armed revolution can be totally bad) this is a superb opener: the TARDIS crew visit the titular museum and find time is askew: dropped glasses return to hands, whole outfits change in the blink of an eye, no one leaves any footprints. Then they discover an exhibit that chills them to the bone: themselves.

7. The Time Meddler – The Watcher/Part One

(Season Two, 1965, written by Dennis Spooner and directed by Douglas Camfield)

In its second series, Doctor Who was frequently experimenting; writer and Script Editor Dennis Spooner here follows his comedic ‘The Romans’ with a more successfully funny script, inventing a subgenre that became known as ‘Pseudo-historicals’: essentially allowing for anachronisms and alien-invasions of history.

‘The Time Meddler’ is accordingly funny, inventive and bold. New companion Steven is set to bickering with Vicki, who remains one of the best characters of the Sixties thanks to Maureen O’Brien’s irrepressible enthusiasm and comic timing. Peter Purves, of Blue Peter and Crufts presenting fame, plays Steven a little like Hartnell’s early Doctor in that he’s a smart grouch who gets taken along for the ride. Hartnell nails some of the Doctor’s best comic moments. The fizz of the series’ invention here is quite something to see.

8. The Myth Makers – Small Prophet, Quick Return/Part Two

(Season Three, 1965, written by Donald Cotton and directed by Michael Leeston-Smith)

The TARDIS crew are the titular myth-makers, but the story’s treatment of the mythic is bleakly hilarious: set around the siege of Troy we have Odysseus and Priam, Helen and Cassandra; all rendered as ugly personalities, people far from the stuff of legend. Like Blackadder Goes Forth the comic bickering is building to something, but the second episode is the comic high point of Donald Cotton’s witty script.

9. The Tenth Planet – Episode Two

(Season Four, 1966, written by Gerry Davis and Kit Pedler and directed by Derek Martinus)

The Doctor, Ben and Polly arrive at the South Pole spaceship tracking station in 1986, only to find ships going out of control and a new but familiar planet in the sky. Outside, a flying saucer touches down. The Cybermen have arrived.

What really works about this introduction is the contrast between the impassive, sing-song voiced cyborgs and the very emotional human response to astronauts in danger; when Ben escapes and kills a Cyberman he’s clearly upset by it. The contrast only serves to make the Cybermen seem more uncanny, and really this is the only TV story that leans into this until at least 2006.

10. The Power of the Daleks – Episode Six

(Season Four, 1966, written by David Whitaker and Dennis Spooner, directed by Christopher Barry)

The Doctor, having regenerated, is a very different person and while Polly is sure that it’s the same person, Ben isn’t. They land on a human colony and discover they are trying to revive a crashed Dalek ship. The Doctor’s warnings go unheeded as the Daleks manipulate the colonists into reviving more of them. Finally, in this last episode, the promised carnage is unleashed in a cacophony of screams, gunfire and mechanical voices.

The release of tension is unbelievable here, and the coldness of the many deaths almost overwhelming. To cap it all, the new Doctor isn’t a reassuring figure yet. Some incredibly bold choices were made making this story.

11. The Web of Fear – Episode Four

(Season Five, 1968, written by Mervyn Haisman and Henry Lincoln and directed by Douglas Camfield)

This base-under-siege story overcomes the limitations of its formula by actually making everyone pretty competent. There isn’t a base commander prolonging the story by being suspicious at the incomers, there’s a general air of paranoia due to the antagonist seemingly knowing the army’s every move. And when said antagonist is a shapeless entity who has animated some robot yetis that spray a deadly mist/fog that horribly kills anyone it touches… this is alarming. In this episode, friends are kidnapped and possessed. Soldiers are killed despite actually being good at their jobs, in action sequences directed with pace and clarity. The deaths really land.

12. The Mind Robber – Episode One

(Season Six, 1968, written by Derrick Sherwin and Peter Ling and directed by David Maloney)

An extra episode had to be added to Peter Ling’s four-part story, and so Script Editor Derrick Sherwin came up with a first episode making use of existing sets, props and a white void. This lead-in uses the TARDIS crew of the Doctor, Jamie and Zoe to expand their backstories and build an air of unease before a startling cliffhanger where everything seems to fall apart.

13. The War Games – Episode Nine

(Season Six, 1969, written by Terrance Dicks and Malcolm Hulke, directed by David Maloney)

The Doctor, Jamie and Zoe find themselves in the trenches of World War One, but why is there an English Redcoat in prison? Where does the General keep disappearing to? And why is there a Roman legion roaming around outside? These are the war games, and they need to get hold of whoever’s running them.

There is an unspoken issue with ‘The War Games’, which is that it’s ten episodes long and so inevitably repeats itself. This is where the story is finally able to emerge from its holding pattern for a game-changing finale, but the last vestiges of said holding pattern – the bickering baddies with their satisfying petty squabbles, Philip Madoc being icy cool as their boss, a burgeoning romance among the players – remind you of why you enjoyed the journey here.

14. The Silurians – Episode Six

(Season Seven, 1970, written by Malcolm Hulke and directed by Timothy Combe)

The Doctor is sent with Dr Liz Shaw and UNIT to investigate the power losses at an underground nuclear base in Derbyshire, and it turns out these are due to a colony of lizard-people who ruled the Earth before humanity. Can the Doctor find a peaceful solution to both sides’ increasing antagonism?

No.

15. The Three Doctors – Episode One

(Season 10, 1973, written by Bob Baker and Dave Martin and directed by Lennie Mayne)

People are disappearing. Strange creatures, who look like they’re made of bubbles blown in a bloody milkshake, are attacking UNIT headquarters. The Time Lords are powerless to stop a relentless energy drain, but send the only person who can help the Doctor in the circumstances: himself.

I mean, come on, if you’re not on board after that description what are you even doing on this website?

16. Carnival of Monsters – Episode One

(Season 10, 1973, written by Robert Holmes and directed by Barry Letts)

The Doctor and Jo arrive on a ship under attack from a plesiosaur, while on a far and distant planet some entertainers find themselves under interrogation from a group of grey-faced administrators. How, though, are the two places connected?

Similar to ‘The Space Museum’, though with a more popular next three episodes, ‘Carnival of Monsters’ drip-feeds clues to the audience before a bravura cliffhanger. It’s is a really funny concept delivered with panache by the actors, taking the piss out of the BBC management and gently mocking Doctor Who itself.

17. The Ark in Space – Part Three

(Season 12, 1975, written by Robert Holmes and directed by Rodney Bennett)

The Doctor, Sarah and Harry arrive in a seemingly abandoned space station in the far future, and discover a large group of humans in suspended animation. Unfortunately a Wirrn Queen/giant pregnant wasp has got on board and laid its eggs in one of the technicians.

Essentially Alien for children, ‘The Ark in Space’ embodies producer Philip Hinchcliffe’s wish to intensify the horror. Part Three opens with the space station commander removing his bright green mutating hand from his pocket while the voice of the long dead Earth High Minister gives a rousing speech about how they’re going to save humanity, and doesn’t let up from there. The Doctor nearly kills himself accessing the Queen’s memories while Wirrn grubs try to kill everyone. It’s unrelenting.

18. Genesis of the Daleks – Part Four

(Season 12, 1975, written by Terry Nation and directed by David Maloney)

The Time Lords send the Doctor, Sarah and Harry back in time to avert the creation of the Daleks. This goes really badly.

The Doctor has just failed to avert the Thal attack on the Kaleds’ city, meaning the Kaleds have all been wiped out, apart from their scientific elite (protected in their underground bunker) and the Daleks. After having given the Thals the means to destroy his own people, Davros – the creator of the Daleks – unleashes his creation on them. Astonishingly bleak.

19. The Deadly Assassin – Part Four

(Season 14, 1976, written by Robert Holmes and directed by David Maloney)

The Doctor is summoned to Gallifrey and has a premonition that the President will be assassinated. Due to a series of unfortunate misunderstandings, the Doctor is then arrested for assassinating the President. In trying to clear his name he uncovers a plot amidst the festering complacency.

Part Three of ‘The Deadly Assassin’ features the Doctor and a masked antagonist inside a virtual domain where the conventional rules are suspended. A battle of wills and a hunt for survival ensue, with the Doctor hunted and hunting. It’s unlike anything else in the show’s history.

20. The Robots of Death – Part Four

(Season 14, 1977, written by Chris Boucher and directed by Michael E. Briant)

Come, see the huge mining ship sweeping a desert planet for minerals, crewed by money-driven sociopaths who work in luxurious outfits while robots do the labour. And then the murders start! Part four reveals who’s behind everything, and even if you guessed correctly you may not be prepared for how unhinged this person is. A grisly, intense, occasionally hilarious tale with one of the saddest instances of someone’s head exploding in Doctor Who history.

21. The Horror of Fang Rock – Part Three

(Season 15, 1977, written by Terrance Dicks and directed by Paddy Russell)

In which the Doctor, Leela, three lighthouse keepers, a bosun and some awful posh people are trapped in a lighthouse with a shape-shifting alien that wants to kill them all. Terrance Dicks’ script is efficient, Paddy Russell’s no-bullshit direction points the cast in the right direction, and there’s a fine streak of morbid comedy throughout. Part Three is where, after a few deaths and ominous forebodings, things start getting really bad.

22. The Ribos Operation – Part Three

(Season 16, 1978, written by Robert Holmes and directed by George Spenton-Foster)

The Doctor is assigned by the enigmatic White Guardian to find and assemble THE KEY TO TIME because the universe needs to be turned off and on again. He is sent Romana, a recent graduate from the Time Lord Academy, to help him. Romana turns out to be Mary Tamm in a series of Lady Penelope costumes, and frequently punctures the Doctor’s ego.

Part Three of this gods-and-monsters crime caper contains two of the best scenes in Doctor Who: the scene where one of a pair of conmen hides from the authorities with Binro the Heretic, which does nothing to advance the plot but is one of the most important scenes in the entire story; and the bit where a vainglorious war lord strikes the Doctor with his glove in rage and the Doctor is camply affronted.

23. The Pirate Planet – Part Three

(Season 16, 1978, written by Douglas Adams and directed by Pennant Roberts)

Douglas Adams’ debut and best script for Doctor Who continues the quest for THE KEY TO TIME in an ostensibly whimsical tale of cyborg pirates and mildly enthusiastic golden ages that also features the highest death toll the show has seen up to this point. Come for the fight between K9 and a robot parrot, stay for the righteous fury underpinning the whole story and Tom Baker’s best piece of acting in his entire seven-year tenure.

24. The Androids of Tara – Part Three

(Season 16, 1978, written by David Fisher and directed by Michael Hayes)

The Doctor and Romana continue their quest for THE KEY TO TIME on the planet Tara, where the Doctor promptly goes fishing and Romana finds the next segment of the key in about five minutes. Then she gets caught up in the Machiavellian schemes of Count Grendel of Gracht, as Doctor Who homages The Prisoner of Zenda.

David Fisher’s script is relentlessly entertaining, and Peter Jeffrey’s performance as Count Grendel is incredible. A rip roaring, witty adventure, Part Three is the funniest episode, yet also has surprising moments of pathos and depth to it.

25. City of Death – Part Two

(Season 17, 1979, written by Douglas Adams and Graham Williams – based on a story by David Fisher – and directed by Michael Hayes)

In which the Doctor and Romana are on holiday in Paris, and along with punch-drunk detective Duggan they investigate the curious crimes of Count Scarlioni, a man who appears to have seven original versions of the Mona Lisa in his cellar.

After a slightly choppy episode of set up, Part Two of ‘City of Death’ may be utterly perfect. Not to say the rest of the story is bad (it’s witty and funny and serious when it needs to be), but Part Two can legitimately lay a claim to being the best single episode of the show ever. It starts with the ‘What a wonderful butler, he’s so violent’ scene, continues to the mystery of the Seven Mona Lisas, and then ends with a cliffhanger that turns the entire story on its head. Perfect.

26. The Keeper of Traken – Part One

(Season 18, 1981, written by Johnny Byrne, directed by John Black)

The Doctor and Adric are surprised to find an old man on a throne in the TARDIS. This is the titular Keeper, a being who dedicates their life to maintaining the idyllic life of the Traken union. The Doctor enigmatically remarks “They say the atmosphere there was so full of goodness that evil just shrivelled up and died. Maybe that’s why I never went there.”

However, in this case evil has not shrivelled up and died, something has taken root. The consuls of Traken are clearly bickering and complacent. Something is rotten. This is the story of the death of a fairy tale.

27. Enlightenment – Part Two

(Season 20, 1983, written by Barbara Clegg, directed by Fiona Cumming)

The Doctor, Tegan and Turlough are given forewarning of something ominous and terrible happening, and then land in a ship’s hold before meeting the crew. The officers seem distant and aloof, the sailors slightly confused about exactly what they’re doing there. The one thing they agree on is they’re taking part in a race. The prize: Enlightenment, which Captain Striker refers to as “The wisdom which knows all things and which will enable me to achieve what I desire most”.

The strangeness of the officers is superbly acted, the characters chilling and enigmatic, tragic and powerful. Turlough and Tegan both get plenty to do, and Peter Davison’s Doctor excels in stories like this where he can be slightly behind events but his earnest pursuit is rewarded.

28. The Caves of Androzani – Part One

(Season 21, 1984, written by Robert Holmes and directed by Graeme Harper)

The Doctor and Peri, who joined the TARDIS in the last story, land on Androzani Minor and find themselves infected with a deadly disease before being arrested for gun-running. There’s a lot to enjoy here: the deft worldbuilding (setting up the army in opposition to the gun-runners with the politicians of Androzani Major), with characterisation equally effortless (the moment the President sees an execution and states “In my day we had filthy little swine like that shot in the back. The red cloth was for soldiers” – you know exactly who this man is). Right up until the cliffhanger, where the Doctor and Peri face a firing squad, there’s a solidity to the production that’s only increased when everyone opens fire.

29. The Caves of Androzani – Part Four

(Season 21, 1984, written by Robert Holmes and directed by Graeme Harper)

The Doctor starts this episode screaming in defiance and crashing a spaceship into a planet, and ends it sacrificing his life to save Peri. In between here and there we have the almost operatic tragedy of Sharaz Jek, the stunningly brutal despatch of the army General and Major, the gun-runners turning on each other, and the betrayal of Morgus by his secretary. It’s just pay-off after pay-off, making this one of the greatest ever stories.

30. Paradise Towers – Part Two

(Season 24, 1987, written by Stephen Wyatt and directed by Nicholas Mallett)

Have you ever read High Rise by J.G. Ballard and thought ‘Wow, I wonder what this would look like as a CBBC production’? Well good news, because in 1987 someone did this (though no-one has tried it with ‘Crash’). ‘Paradise Towers’ turns social commentary into a broad pantomime by way of 2000 AD, a hyper-real depiction of high-rise flats populated by grotesques and posh delinquents.

Here we get the Seventh Doctor running rings around the building’s caretakers using their own rule book, Mel being led around the towers by the Pex – a coward trying to be an action hero – and the lovely old ladies having a naughty secret. Big broad fun that sees the show changing in a significant way.

31. Remembrance of the Daleks – Part One

(Season 25, 1988, written by Ben Aaronovitch and directed by Andrew Morgan)

The Doctor and new companion Ace arrive in London, 1963, as the Doctor has unfinished business. There are strange markings in the playground of the local school, and an old enemy in a familiar junkyard.

Set in and around the location of the very first episode, there are callbacks aplenty, but these are grace notes rather than essential elements. Setting up the story’s characters and themes with aplomb, it’s also drily witty, action-packed and assuredly confident.

32. Remembrance of the Daleks – Part Four

(Season 25, 1988, written by Ben Aaronovitch and directed by Andrew Morgan)

‘Remembrance of the Daleks’ is a story about racism, using the Dalek Civil War (established in ‘Revelation of the Daleks’) as a starting point before looking at racism within the lifetime of Doctor Who: here it is in the family home, in the café, in the local builders, and in the precursor to UNIT.

This episode also looks really cool. When the Daleks land a shuttle in the school playground, the BBC lower a massive wooden prop into the playground on a crane. While it might have been built from old bins, the Special Weapons Dalek is a serious bit of hardware (the explosions in this episode almost demolished a location that belonged to ITV, and had the police come out to check that it wasn’t the IRA). More than just the strong visuals, though, this episode builds to what was a jaw-dropping finale at the time, ending on a note of uncertainty that underscores everything we’ve just seen.

33. Ghost Light – Part Three

(Season 26, 1989, written by Marc Platt and directed by Alan Wareing)

The Doctor and Ace arrive at Gabriel Chase in 1883, and are immediately thrust into a world of exaggerated Victorianism, mental instability, nefarious regal supplantation schemes, and an angel in the basement who’s really committed to their database.

‘Ghost Light’ has a reputation for being hard to follow but I disagree. It’s extremely easy to follow in its wake, even if you’re not entirely sure how all the events relate to each other. It’s relentlessly entertaining, slightly unsettling and has got the best joke about murdering and eating a policeman ever broadcast. Part Three also features the Doctor really annoying a nerd by telling him that he’s bad at gatekeeping – a complete mystery where they got that idea from.

34. The Curse of Fenric – Part Three

(Season 26, 1989, written by Ian Briggs and directed by Nicholas Mallett)

The Doctor and Ace arrive at a navy base during WWII where a coding machine is being worked on. A small force of Russian soldiers have arrived to steal it. Another force is lurking nearby, waiting to be unleashed. The Doctor never could resist a game of traps.

‘The Curse of Fenric’ is another unusually structured Seventh Doctor tale, with the first three episodes involving characters moving around the locations and discovering clues while an increasing amount of hell breaks loose. Part Three is where all the character drama happens before chaos is unleashed in Part Four: the question of faith – who has it and what is it in – is explored through the medium of fighting vampires, the base commander explains why he’s locked soldiers in a tunnel with said vampires, and Ace finally loses it at the Doctor’s manipulations. By the time an ancient evil has arisen and the base is being besieged by vampires you could do with a week to recuperate.

35. Survival – Part One

(Season 26, 1989, written by Rona Munro and directed by Alan Wareing)

The Doctor and Ace return to Ace’s home, the town of Perivale in North West London, to see how Ace’s friends are doing. Most of them are gone, either to escape the all-encompassing boredom or because they’ve been kidnapped by cheetahs on horseback and taken to another planet.

With a mix of heavily theatrical thematic dialogue and something approaching how people actually talk, Rona Munro’s script allows Sophie Aldred to shine and gives suburban kids a reason to be cautious around gammy-looking cats. It’s more common now, but it was genuinely unusual to see the Doctor cutting about the suburbs, annoying curtain twitchers and being pursued by the Neighbourhood Watch.

36. Dalek

(Series One, 2005, written by Rob Shearman and directed by Joe Ahearne)

The Doctor and Rose arrive at an underground base filled with alien tech, where a billionaire collector has a prize item: the Metaltron, a live alien who refuses to speak.

The public reputation of the Dalek was as a slightly kitsch pop-culture object, mostly remembered by a joke about them not climbing stairs, having plungers for arms or appearing in KitKat adverts with Bernard Manning. Rob Shearman had to overcome this perception of them.

‘Dalek’ is the story of one lone Dalek systematically and capably wiping out nearly everyone in the base in an efficiently cruel way, while retraumatising the Doctor and being disgusted by its own capacity for empathy. The plunger is now deadly. A Dalek can very definitely climb stairs, being now an unstoppable tank controlled by a genocidal Nazi octopus, who would rather die than be anything else. All in all, quite a successful rehabilitation of a public image.

37. Father’s Day

(Series One, 2005, written by Paul Cornell and directed by Joe Ahearne)

Rose wants to travel back in time to see her Dad die in the Eighties. The Doctor, infatuated with her, agrees to this even though it’s – at best – a risky move. And so it proves, with Rose saving her Dad’s life and causing a temporal incident that unleashes monsters and destroys the world. Once the monsters – Reavers – are unleashed, most of the story takes place in a church people were heading to for a wedding. The destruction of Earth is represented by the shrieks of the creatures as they fly around outside, waiting to get in.

The scale of the destruction, and it being unseen, makes this more unsettling for the trapped survivors, but the main part of the story is Rose meeting her Dad and learning that her Mum told her an idealised version of events. Pete Tyler is a bloke, trying his best, but flawed and aware of it. The scene where Rose pretends that he lived, and lies about what they did together, and Pete just responds with ‘That’s not me’ is – as with so much of this story – heart-breaking.

38. The Doctor Dances

(Series One, 2005, written by Steven Moffat and directed by James Hawes)

The Doctor and Rose chase a metallic object giving off danger signals through the vortex into WWII London. There, Rose meets Captain Jack who is hanging out in an invisible spaceship by Big Ben, while the Doctor meets a boy in a gas mask with a strange wound on his hand, continually asking “Are you my mummy?”

This is essentially a zombie horror for children, which opts for the strange and unsettling rather than gore. The repeated plaintive chime of ‘Are you my mummy?’ and the act of touch transmit this plague, and no matter how dated the CGI is there’s always going to be something disturbing about seeing respected actors’ heads slowly and crunchily morph into a gas mask. Despite all this, it’s home to a burst of pure joy for this most traumatised of Doctors.

39. The Parting of the Ways

(Series One, 2005, written by Russell T. Davies and directed by Joe Ahearne)

The Doctor, Rose and Captain Jack find themselves in some very 2005 TV parodies, before escaping and discovering that the entire operation is a means to provide an insane Dalek Emperor with living matter from which to secretly build a new army.

The story segues smoothly from pop culture parodies to the attempted destruction of Earth, and you realise this whole series has been about Christopher Eccleston’s Doctor coming to terms with what he believes he did to end the Time War, providing him with a comparable scenario and seeing if he’s willing to go through with it a second time. It’s intense, moving, and Eccleston’s performances against the Daleks are unlikely to be bettered.

40. Smith and Jones

(Series Three, 2007, written by Russell T. Davies and directed by Charles Palmer)

Martha Jones is a medical student who meets a man in the street, only to find him in bed at her hospital. Which is then transported to the moon. By rhino-like aliens.

No-one writes tonal dissonance like Russell T. Davies. The combination of wonder, awe, panic and fear at the hospital on the moon, the comedy of alien race the Judoon with their rhino-faces and rhyming language juxtaposed with their extreme methods of dispensing justice, and the delightful camp nastiness of the antagonist and her straw all add up to an extremely good time. ‘Smith and Jones’ introduces Martha to the show while juggling umpteen plates and makes it look absolutely effortless.

41. Gridlock

(Series Three, 2007, written by Russell T. Davies and directed by Richard Clark)

In which the Doctor takes Martha to New Earth, where he’d previously taken Rose, to discover that it’s empty because everyone is stuck in a colossal traffic jam.

As well as emanating a McCoy era comic-book energy, ‘Gridlock’ reflects the leads’ strained relationship at this point. The Doctor, pining for the absent Rose, isn’t very open, and Martha, pining for the absent-but-frustratingly-also-right-bloody-there Doctor, is getting fed up over his emotional distance. There’s an ongoing theme about faith in this series, here it’s about the support it can give you in hard times, reflected in the Doctor’s descriptions of Gallifrey and the Time Lords to Martha, and whether or not that faith is ultimately restricting.

42 & 43. Human Nature and The Family of Blood

(Series Three, 2007, written by Paul Cornell and directed by Charles Palmer)

Based on Paul Cornell’s Nineties novel ‘Human Nature’, this sees the Doctor and Martha on the run from the Family of Blood, and the Doctor taking on human form to try to evade them. He becomes John Smith, a teacher at a boarding school in 1913, with Martha working as a maid. Unfortunately the Family find them, possess human bodies, and attempt to make a bewildered Smith turn back into the Doctor.

In the book, the Seventh Doctor becomes human to better understand his companion’s grief. Here, fittingly for his character, the Tenth Doctor becomes human as part of a rushed plan that puts Martha into a terrible position and endangers the lives of everyone around him. There’s this mercurial rush of energy and charisma that takes people along with him before the bodies start cooling. This story is the best depiction of this.

44. Midnight

(Series Four, 2008, written by Russell T. Davies and directed by Alice Troughton)

The Doctor decides to go on a little tourist shuttle trip around an ice planet, getting to natter away to some strangers and see some shiny things. As long as an ineffable entity doesn’t trap them all and possess one of the passengers, it’ll be absolutely lovely.

It’s not an especially original observation to make, but Russell T. Davies is very good at writing TV characters. We’re introduced to an ensemble cast and know the basics of their relationships and personalities extremely quickly. The possession also cleverly weaponises characterisation: An entity that steals voices, mimics and learns is one that the Doctor – especially this Doctor – is going to struggle against. And so it proves. A riveting and haunting episode, for what is essentially half a dozen people arguing in a space bus.

45. The Eleventh Hour

(Series Five, 2010, written by Steven Moffat and directed by Adam Smith)

The newly regenerated Doctor (Matt Smith) crash lands in Amelia Pond’s back garden. Returning years later than he intended, he discovers no one living in the house, a suspicious police woman, and the precursor to an alien invasion.

Under immense pressure following the incredibly popular combination of David Tennant’s Tenth Doctor and showrunner Russell T. Davies, new showrunner Steven Moffat and then relative unknown Smith perform a soft reboot of the show that’s a perfect start for the new and continuation of the old. From the second Smith sticks his head out of the TARDIS door and chirps “Can I have an apple?” we knew everything was going to be alright.

46. Vincent and the Doctor

(Series Five, 2010, written by Richard Curtis and directed by Jonny Campbell)

The Doctor and Amy, whose husband recently ceased to exist so she can’t remember him, visit and befriend Vincent van Gogh. Meanwhile, a heavily metaphorical monster is hiding out in a nearby church.

A surprisingly sensitive script from Richard Curtis, you can feel his passion for the subject shining through. The scene where van Gogh is shown his future reputation as one of the great painters is celebrated, as is the moment where Amy realises that this doesn’t alter the fact that he will still take his own life, but there are also moments of great visual splendour here: the scene where van Gogh describes how he sees the night sky, and the accompanying visuals, are an unabashed celebration of creativity and a vibrant high point.

47. & 48. The Pandorica Opens and The Big Bang

(Series 5, 2010, written by Steven Moffat and directed by Toby Haynes)

The Doctor and Amy find River with a Roman legion while investigating Stonehenge. There, they find the Pandorica, a legendary prison, and the Doctor’s enemies in wait.

Series Five kept the rough structure of the previous four series, and so here we get to see Moffat writing a Russell T. Davies-style finale. Or at least, half of one. While ‘The Pandorica Opens’ escalates the stakes towards the cliffhanger, ending on the Doctor being trapped, River exploding, Amy being shot, and the entire universe exploding (essentially going nuclear on the Series Finale cliffhanger concept by destroying absolutely everything all at once) we then head into ‘The Big Bang’, and see a Steven Moffat finale in action. Like ‘Forest of the Dead’ this is very different to its first episode, going smaller and more intimate (as if there were an option after the last episode) before a melancholy and then joyous ending.

49. A Christmas Carol

(Christmas Special, 2010, written by Steven Moffat and directed by Toby Haynes)

The Doctor attempts to reason with Ebenezer Scrooge surrogate Kazran Sardick (Michael Actual Gambon) in order to stop the spaceship where Amy and Rory are roleplaying from crashing. The more successful Doctor Who version of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (Season 23 is also loosely based on it) featuring the inevitability of death, singing and flying sharks.

50. The Night of the Doctor

(Mini-episode, 2013 written by Steven Moffat and directed by John Hayes)

A mini episode in which we were promised one of either David Tennant, Matt Smith or John Hurt would appear: a spaceship is crashing and its occupant is trying to get the computer to send a distress call, while it asks her if she needs a Doctor. At which point, lo and behold! The Eighth Doctor (Paul McGann) appears with the line “I’m a Doctor, but probably not the one you were expecting”.

McGann’s Doctor appeared once on screen in the 1996 TV Movie, which didn’t result in an ongoing series. Bringing him back specifically to regenerate into John Hurt’s War Doctor scratched the itch many fans had to see McGann play the role again. A short episode, sure, but one that succeeds as a strong, tragic regeneration story for McGann’s take on the role.

51. The Day of the Doctor

(50th Anniversary Special, 2013, written by Steven Moffat and directed by Nick Hurran)

The 50th Anniversary Special. The Tenth and Eleventh Doctors meet the War Doctor – a previously unknown incarnation between the Eighth and Ninth Doctors – at the point just before he destroys Gallifrey in the Time War.

Considering there was a point where only Jenna Coleman was contracted to appear in this episode, it turned out rather well, being both celebratory and a great yarn in its own right. David Tennant and Matt Smith have great fun together, Billie Piper doesn’t have to remember how to play Rose again after being cast as a sentient superweapon instead, and gets to cut loose a bit too, and John Hurt is inspired casting as someone representing all the previous Doctors and the weight of centuries of war.

52. Mummy on the Orient Express

(Series Eight, 2014, written by Jamie Mathieson and directed by Paul Wilmshurst)

This is the moment the Capaldi era sparks into life. After falling out in the previous story, the Doctor takes Clara on one last adventure to the Orient Express (in space). Coincidentally people onboard are dying in strange ways, which turn out to be caused by a Mummy that only the victim can see. The Doctor proceeds to both save the day and alienate nearly everyone on the train.

A great monster, and a great story hook, but what really stands out here is the characterisation. The scene where the Doctor gets Clara to bring a potential victim to him, asking her to lie for him, is brutal, and the fallout on the beach afterwards is key to letting the Twelfth Doctor seem something other than cold and indifferent. Pivotal to the following series is the understanding that, while the Doctor might be off-putting and clearly unhinged, the reason that Clara wants to travel with him in the end is simple: she is too.

53. Flatline

(Series Eight, 2014, written by Jamie Mathieson and directed by Douglas Mackinnon)

The Doctor is trapped in a shrunken TARDIS, so Clara has to investigate the mystery of killer graffiti in Bristol largely by herself. ‘Flatline’ is a consistently inventive horror story that takes something everyday and weaponises it. In this case: two dimensional patterns. Drawings. Even the ground you’re walking on. The second half of Series Eight remains a really strong run of stories.

54. Last Christmas

(Christmas Special, 2014, written by Steven Moffat and directed by Paul Wilmshurst)

In which the Doctor and Clara work through their emotional baggage with the help of killer crabs, the 2010 Christopher Nolan movie Inception, and Santa.

Not many shows could make a story where Facehugger-like crabs that make you dream are a key part of a Christmas special, but here we are.

55. & 56. Heaven Sent and Hell Bent

(Series 9, 2015, written by Steven Moffat and directed by Rachel Talalay)

In which the Doctor finds himself trapped in a castle where the rooms move, and a Death-like figure stalks him, all the while trying to grieve the death of Clara. ‘Hell Bent’, the follow up episode that only cowards pretend is separate from ‘Heaven Sent’, deals with the repercussions of this.

In some respects it’s a textbook Moffat season finale: the second episode is a complete rug-pull from the first, finding a more thoughtful and interesting story to tell. In this case though, ‘Hell Bent’ really pushes against the idea of the Doctor’s heroism and delves into the uglier facets of the character. It can take a few views to settle, but it grows on each viewing and also enhances the more straightforwardly popular ‘Heaven Sent’ in the process.

57. The Husbands of River Song

(Christmas Special, 2015, written by Steven Moffat and directed by Douglas Mackinnon)

The Doctor arrives in the middle of one of River Song’s adventures, and due to his regeneration, she doesn’t recognise him, so he ends up being her companion on a crime escapade featuring the removal of several popular comedians’ heads. After forty-minutes or so firmly in romp mode, the story focuses purely on the Doctor and River, bringing their story full circle. It’s a really sweet, tender ending and shows signs of the Doctor maturing: the idea of him actually settling down with one person in one place had previously been treated as a joke, now it’s something he does willingly.

Hopefully Yaz never watches this episode. That’d be awkward.

58. Thin Ice

(Series 10, 2017, written by Sarah Dollard and directed by Bill Anderson)

The Doctor takes Bill to a fair on the frozen Thames in 1814, and discovers something alien beneath the ice.

Remembered more for the Doctor punching a racist than anything else, ‘Thin Ice’ is one of the great depictions of the Twelfth Doctor: there’s an appropriate coldness to him here as he sees a child die and doesn’t flinch, attempts to wriggle out of questions about whether he’s killed anyone, and brings Bill with him on this journey. There’s that permanently unsettling quality about Capaldi’s Doctor, a sense that he likes getting into the abyss just to see if he can get out again. You get this easy-to-follow, engaging procedural with excellent characterisation that leans in towards the more anarchic side of the Doctor over the liberal one (as exemplified by, yes, the scene where he talks to Bill of reason over passion, and then lamps Racist Nathan Barley).

59. The Doctor Falls

(Series 10, 2017, written by Steven Moffat and directed by Rachel Talalay)

The Doctor, hoping that Missy really is capable of changing her ways, lets her ‘do’ an adventure herself with Bill and Nardole as her unwilling companions exploring a spaceship. Despite, or possibly because of, his desperate intervention, Bill is critically wounded and rushed to the other end of the ship to be operated on. Due to the effects of a nearby black hole, time dilation means time passes differently at one end of the ship to the other. Can the Doctor get to the other end of the ship in time to save his friend?

This is the closest the show has got to another ‘Caves of Androzani’, with the Doctor sacrificing himself to buy his friends time after getting them into the mess in the first place. On top of that, it’s also an incredible Cyberman story. And Master story. And another Master story.

60. Demons of the Punjab

(Series 11, 2018, written by Vinay Patel and directed by Jamie Childs)

A highlight of the Chris Chibnall era, this story starts with Yaz asking the Doctor to go back in time to learn more about her family. They find Yaz’s grandmother as a young woman, but she’s engaged to someone Yaz has never heard of. As they try to work out why, the looming Partition of India threatens to tear the family apart.

During Chibnall’s time as showrunner, Doctor Who looked for areas of history the show hadn’t covered before. As Doctor Who doesn’t seek to change historical events when it depicts them, due to its origins as an education programme, there’s a question of sensitivity when it comes to depicting historical tragedy. What ‘Demons of the Punjab’ does so well is make the fate of one family a microcosm of a greater historical event, an example of Partition’s repercussions, while forcing the Doctor to observe rather than interfere. That sense of conflict feels appropriate here, at least, the Doctor’s powerlessness clearly rankling.

Doctor Who returns on November 25 with ‘The Star Beast’, airing on BBC One and BBC iPlayer in the UK, and on Disney+ around the world.