Doctor Who’s Best Historical Episodes: Aztecs, Greeks, Daleks & Demons

Presenting: the Top 10 Doctor Who historicals.

60 years ago, Doctor Who was created with a strong educational element, mixing science and history facts with adventure. Initially some stories featured no science-fiction elements outside of the TARDIS and its crew. This story format petered out by the fourth season, and ′The Highlanders′ was the last example until ′Black Orchid′ in 1982.

The final story of the second season created the ′Pseudo-historical′ format – a story set in Earth′s history but with an additional science-fiction element to the TARDIS crew. This format persists to the present day. By ′Best Historical Episodes′ here, we don’t mean the dozen or so purely historical stories, but are including pseudo-historical stories too.

Some of these stories have a historical setting based around a historical celebrity (e.g., ′The Shakespeare Code’, ′The Unicorn and the Wasp′). Others are more intertwined with historical events and use that setting as a springboard for their stories, but they all represent the best the show has delivered so far.

10. Father’s Day (Series 1, 2005)

Written by Paul Cornell, directed by Joe Ahearne.

By 2005, Doctor Who had already looked back into the recent past, with 1988-broadcast stories set in the early-Sixties. In ‘Father’s Day’, we have a story set in 1987 with the fashion and music of the era present and correct.

This story is based around Ninth and Tenth Doctor companion Rose (Billie Piper), the day that her Dad died, and the legacy of that loss for her. When Rose goes back in time and saves her Dad’s life, it brings about a change to the timeline that attracts creatures called Reapers, who besiege the characters in a church.

This is a rare case of changing the timeline in Doctor Who for an event that doesn’t appear in history books. (Whenever someone mentions fixed points in time it’s always some significant event in Earth′s history rather than, say, some woman on Delphon losing her keys.) This story looks at someone’s personal history and really commits to its stakes, with the Doctor seemingly erased from time for a while before Pete Tyler – heavily based on Cornell’s own dad – sacrifices himself. This really commits to the new version of the show, exploring similar territory to Russell T. Davies novel ‘Damaged Goods’, and making the personal as dramatic and moving a subject as the epic.

9. Demons of the Punjab (Series 11, 2018)

Written by Vinay Patel, directed by Jamie Childs.

′Demons of the Punjab′ is a highlight of the Chibnall era, and probably the closest the show will ever get to the Pure Historical format again. Set on the eve of the Partition of India in 1947, it’s about 13th Doctor companion Yaz’ search for answers about her grandmother’s past, and a mysterious alien threat. The story’s ostensible monsters though, turn out to be red-herrings, actually present to pay their respects to those who would otherwise die alone. It’s a story about family conflict brought about by Partition, a rapid division of the country roughly along lines of religion that escalated migration and violence to unprecedented levels. The province of Punjab was split between the newly formed Pakistan and India, and it′s where the worst violence took place.

Writer Vinay Patel′s story wisely has one family to represent the entirety in microcosm (as with ‘Father’s Day’, the personal is the focus). It doesn’t really tell us much about Yaz as a person, but echoes the McCoy era′s critiques of British Empire by reminding us that the Doctor is an echo of it, unable to interfere because saving a life here means Yaz will no longer exist. ′Demons of the Punjab′ moves the scope of historicals away from Britain and Europe, ably demonstrates the cost of Partition, and does what it does so well that it can′t be repeated any better.

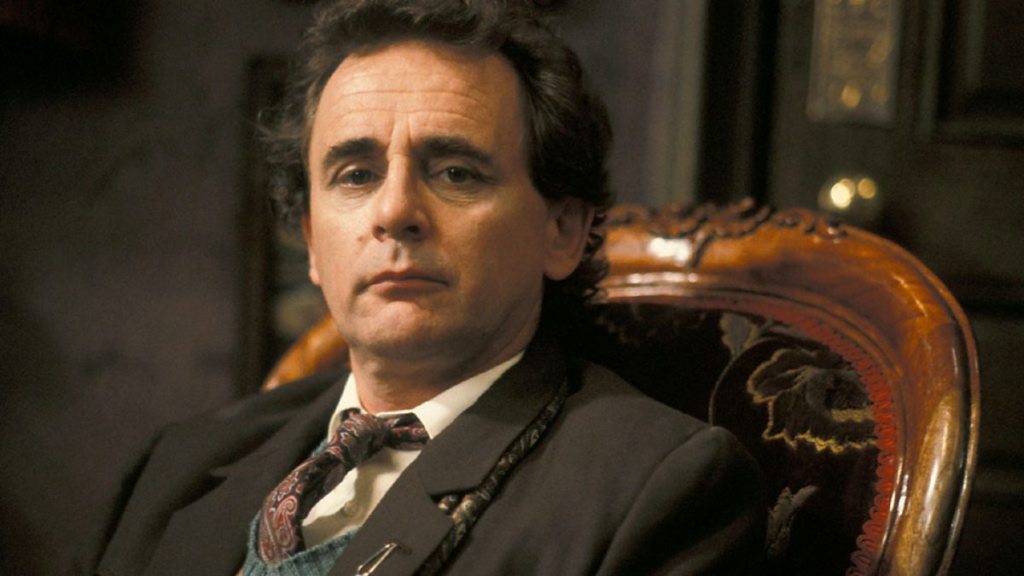

8. Ghost Light (Season 26, 1989)

Written by Marc Platt, directed by Alan Wareing.

In which an angel loses control of its database and Sylvester McCoy’s Doctor annoys it until it explodes. ‘Ghost Light’ is a briskly-paced blackly comic romp through Victoriana, set against a backdrop of Darwin’s theories of evolution and every character’s veneer cracking. This is a very literary Victorian Haunted House with allusions to Blake, Henry James and H Rider Haggard among others.

Originally set on Gallifrey and hugely indebted to Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast novels, ‘Ghost Light’ feels like a precursor to Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen in that it took characters or archetypes of literature and threw them into another story, one where historical knowledge is required of the viewer to understand the situation. Here the sensibilities and fiction that influenced the first 17 years of Doctor Who are repurposed and questioned rather than paid straightforward homage. It’s a relentlessly entertaining, delirious mix – like eating a delicious soup and only finding out what’s in it after you’ve finished.

7. The Eaters of Light (Series 10, 2017)

Written by Rona Munro, directed by Charles Palmer.

This Twelfth Doctor story seemed to slip past unnoticed in Series 10, but it demonstrates why Rona Munro is the only writer to have written for the original run and post-2005 versions of the show. Set around the unexplained disappearance of the Ninth Legion and the theory (popularised by Rosemary Sutcliffe’s children’s novel The Eagle of the Ninth) that they were killed in Caledonia, Munro is able to dabble in some light education about the Pictish tribes and Roman soldiers while finding a different angle on the historical episode that allows much more creative freedom.

It’s a rich and evocative story for and about young people, with teenage characters – in a very on-the-nose move – growing up and literally marching away from Doctor Who – and an echo of magic in the everyday for the youngest viewers, who can now be taken on a journey by the sound of a raven′s caw.

6. Vincent and the Doctor (Series 5, 2010)

Written by Richard Curtis, directed by Jonny Campbell.

This celebrity historical version of ‘Father’s Day’ is focussed around one person where history seems to be being rewritten (Vincent van Gogh is shown a glimpse of the future where he is celebrated as a great artist) but actually isn’t – Van Gogh’s death by suicide is not ultimately averted. This uses the show′s limits as a tasteful restraint, reminding the audience that depression is not something simply resolved, but adding to someone’s happiness is never a bad thing.

Richard Curtis has been, at times, an insensitive writer but here is clearly trying to be respectful of Van Gogh and depression, and to make the point that there are some things that Doctor Who cannot change: it can add things to lives, but it′s not a panacea. It′s also a story that clearly loves art and imagination and isn′t ashamed of saying so.

5. Human Nature/Family of Blood (Series 3, 2008)

Written by Paul Cornell, directed by Charles Palmer.

Set at a boys’ school in 1913 England, ‘Human Nature’ sees the Tenth Doctor take the human form of teacher John Smith in order to hide his Time Lord force from the Family of Blood. It makes a fascinating contrast with Paul Cornell’s book of the same name, which inspired the two-parter and is still widely available for anyone who hasn′t read it. The First World War looms over both versions as the war that rid people of romantic notions of combat reinforced by their schooling, but the TV version is tailored to the Tenth Doctor’s character rather than the Seventh, and changes the pacifism of the original ending.

The book presents a much more idealistic version of the Doctor – in it, he becomes human to understand his companion more and influences schoolboy Timothy to become a conscientious objector – which fits in with the Tenth Doctor’s espoused ideals. On TV, Timothy states that he thinks he will have to fight. This story explores the differences between the Tenth Doctor’s idealism and the reality of him, bringing terror and death in his wake on one level and not considering that his new alter ego might form a deep connection that would have to be severed.

The historical setting is key to this story: the boarding school, the cruelty and racism, the constant reinforcement of harmful masculinity… could all be done today, obviously, but wouldn’t work as well outside of 1913 and its proximity to ‘The Great War’. The recency of the Second Boer War gives us the moment where the Headmaster states he would go back to South Africa where he used his dead friends for sandbags and “would go back there tomorrow for King and country”. This is a stunning moment of horror, adding depth to a character by reinforcing the idea that he would put the younger generation through the hell he experienced for an ideal.

4. The Time Meddler (Season 2, 1965)

Written by Dennis Spooner, directed by Douglas Camfield.

Part of the outpouring of creativity in Doctor Who’s early stages, ′The Time Meddler′ improved upon the comedy elements of ′The Romans′ to play against expectations of the historical story as we knew it in 1965. Set in 1066, it followed a time-travelling monk’s plot to rewrite history by changing the outcome of the Battle of Hastings.

The story is also a demonstration of how strong the character-work could be in Sixties Doctor Who, with writer/Script Editor Dennis Spooner giving all the regulars distinct traits and demonstrating their intelligence. The comedy is, mostly, underplayed and all the funnier for it.

Similarly underplayed is the huge revelation that the strange monk behind all the anachronistic technology has his own TARDIS, a stunning cliffhanger that reveals another member of the Doctor′s as-yet-unnamed race, and one who believes history to be more malleable than the Doctor. In some respects, this is quite a sympathetic outlook, helped by a likeable performance from Peter Butterworth as the Monk.

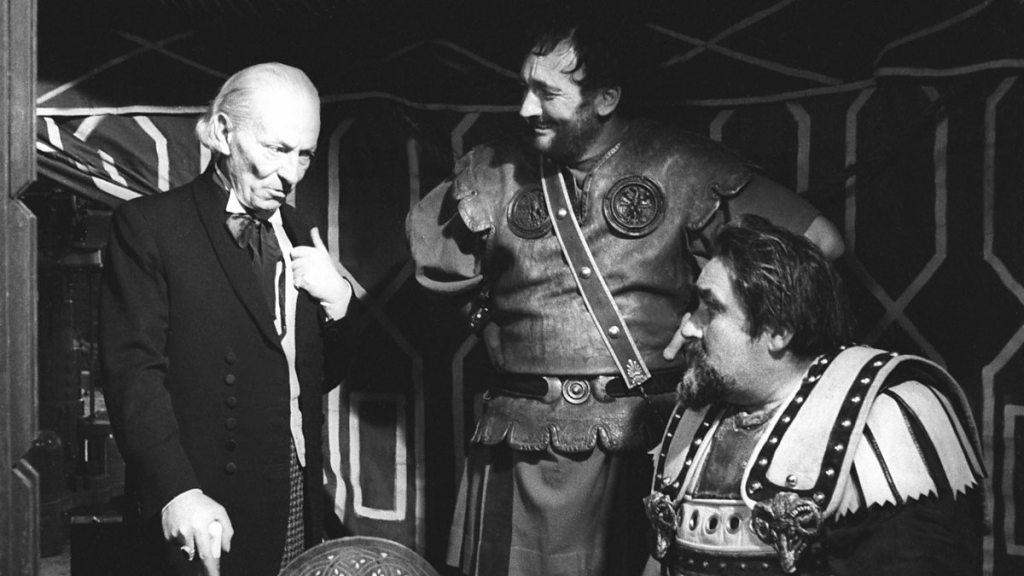

3. The Aztecs (Season 1, 1964)

Written by John Lucarotti, directed by John Crockett.

Lucarotti had already contributed ′Marco Polo′ to Doctor Who – after his extensive research for a Canadian radio serial on the subject – and once the BBC gave the go-ahead for it to continue after its initial 13 episodes, he was asked for another historical story. Having lived in Mexico for a while, he wanted to write a character-driven drama set towards the end of the Aztec civilisation, and as luck would have it, he absolutely did.

Due to Carole Ann Ford being on holiday, First Doctor companion Susan gets the least material here, but the Doctor, Ian and Barbara are all given something dramatic and interesting to do while the educational story scurries along. Ian is, as ever, made to fight someone against his wishes, and wounded pride makes the combat increasingly deadly. The Doctor tries to find a way to get everyone back to the TARDIS, which simultaneously makes Ian′s situation more dangerous and means he gets engaged. There are some fantastic character moments for Hartnell′s Doctor.

Barbara, meanwhile, is mistaken for the reincarnation of the goddess Yetaxa. Given that Barbara was the person who stood up to the Doctor and started him on a more heroic path, it′s a strong choice to put these two characters into conflict again when Barbara attempts to move the Aztecs away from human sacrifice and the Doctor insists that you cannot change history.

This conflict has huge ramifications for Doctor Who as a whole: establishing the sense that history is fixed (understandable given the educational nature of the programme at this point) meaning that the Doctor and, later, the Time Lords are not able to interfere in established events (except, y′know, when they are) giving rise to the concept of fixed points in time.

In the more immediate sense it′s a great moment of character conflict that comes in the wake of the Doctor softening, so there′s more nuance to the arguments. What we get here is a really strong group of characters who drive the plot, expanding what they and the show are capable of, and balancing tension with comedy and little moments of pathos.

2. The Myth Makers (Season 3, 1965)

Written by Donald Cotton, directed by Michael Leeston-Smith.

′The Myth Makers′ is, first and foremost, extremely funny and clever, taking the myths and characters of Greek literature and turning them into a proto-Blackadder. When the First Doctor gets mixed up in the Siege of Troy, we get an extremely venal and vainglorious Achilles, and Odysseus as a bloodthirsty but savvy monster, a butcher with a big broad laugh that grows steadily more sinister through the course of the story. The Trojan court are feckless Bertie Wooster types who ignore the sensible but irritated Cassandra. The comedy and melodrama gives way to the siege itself, which is played straight and terrible.

The effect of this is to render the mythic as something small, petty and almost mundane. In a post-war context, this contains seeds of Blackadder Goes Forth′s rage against distant commanders sending people to die for little or nothing, a warning against romanticising war by making the legendary something ultimately pathetic and brutal.

It also has a novel take on the historical: both Greeks and Trojans believe the Doctor′s claims to be from the future, and so use his knowledge of events unfolding to defeat their opponents. Smart, witty and humane, this is another story whose influence can be seen on the future of the show.

1. Remembrance of the Daleks (Season 25, 1988)

Written by Ben Aaronovitch, directed by Andrew Morgan.

In which the Doctor and Ace arrive in London, 1963, where the Doctor has unfinished business from a previous visit. Meanwhile a UNIT-style army group are investigating unexplained events in Coal Hill, and two factions of Daleks are converging on the area.

This is simultaneously a revisionist history of the in-story universe and a historical about the UK at the time Doctor Who started. That it dares to find fault there is part of an ongoing critique the Seventh Doctor era has against some of the show′s most famous tropes and settings: the sense that rose-tinted spectacles have been judiciously employed around the history of Britain and its Empire.

So we have the Daleks, having a civil war due to their obsession with racial purity, trying to retrieve a superweapon against a backdrop of tolerated obsession with racial purity in Sixties′ London. On top of almost casually making Doctor Who more exciting than it had been in years (big spaceships! Daleks climbing stairs! Explosions so loud the police got called!) this is also a savage, occasionally unsubtle, piece of commentary on Britain. The Doctor’s solution here, famously, is to trap and destroy the Daleks. The scene that lingers is when the Doctor confronts the lone surviving Dalek and goads it into suicide with logic.

After a decade of race riots, reminding viewers of the UK′s history of fascism and how it was tolerated (no one comments on the racist sign in Mrs Smith′s window apart from 1980s-character Ace) and accepted in places such as the army, is a powerful contrast to the nostalgia of the Beatles and the start of Doctor Who. Connecting this to the Daleks is a further stroke of genius: you can′t possibly say this sort of commentary doesn′t belong in Doctor Who when the very creations that popularised the show are an exemplar of it.

Doctor Who returns in November for a three-part 60th anniversary special.