The Most Underrated Sci-Fi Movies of the 1960s

The 1960s was when science fiction cinema began to venture in new directions.

The cinema of science fiction began to mature in the 1950s, concurrent with the arrival of the Cold War and the Atomic Age, as well as the growing sophistication of the literature. But it was during the 1960s that the genre really began to expand in different directions, still heavily influenced by the ideological paranoia and existential dread of the previous decade, but finding even more distinctive expressions of it.

At the same time, the 1960s was also the decade in which sci-fi movies truly started to become event films, not just B-movies and drive-in fodder, as evidenced by the likes of landmarks like 2001: A Space Odyssey and Planet of the Apes, both released in 1968. There were other successes as well, some of them on our list below, but a lot of remarkable sci-fi films of the era did not initially score with critics, audiences, or either. Yet nuclear terror, the future of humanity, and encounters with the unknown still played important roles in the sci-fi movies of the decade. And their evolving maturity spawned some truly amazing films while paving the way for the unfettered imagination and creative independence of the genre’s output in the years to come. Here are 16 of the most underrated science fiction films of the 1960s.

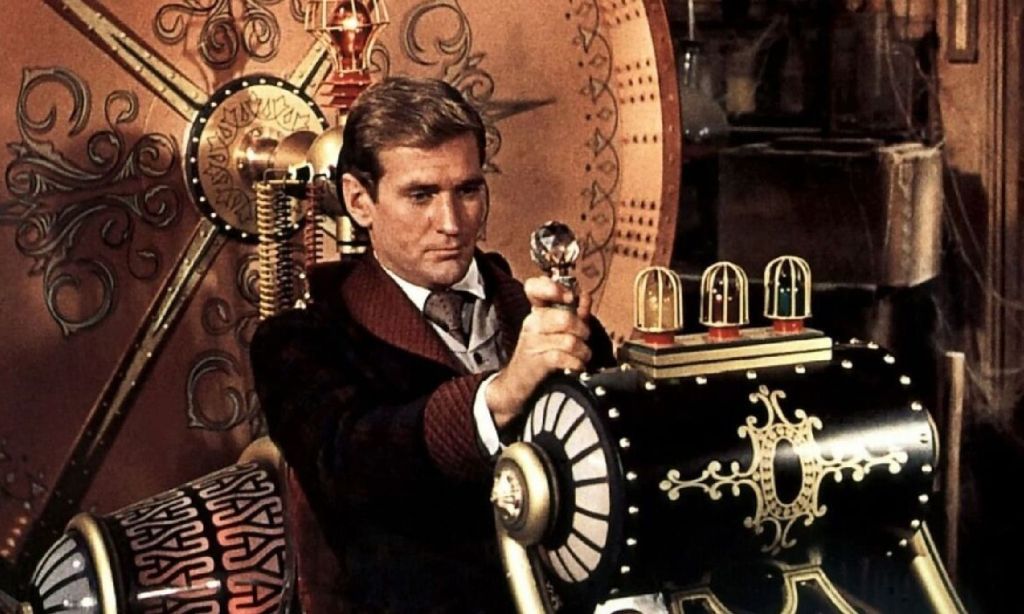

The Time Machine (1960)

George Pal only produced and/or directed 14 live-action movies during a 25-year span, but in some ways he was the Steven Spielberg or James Cameron of his era, delivering big screen, effects-driven, high-concept spectacle while largely working in the genres of sci-fi and fantasy. Seven years after producing the classic The War of the Worlds, Pal produced and directed his second H.G. Wells adaptation, The Time Machine, bringing an action bent to Wells’ somewhat esoteric book with impressive results.

Rod Taylor (The Birds) stars as the inventor (unnamed in the book, called H. George Wells here) whose device catapults him through centuries of war into a future where the child-like Eloi are bred as food for the brutish, monstrous Morlocks. Like Captain Kirk disobeying the Prime Directive, Wells helps the Eloi revolt against the Morlocks before leaving them to their own devices. Although the movie omits the narrator’s final journey 30 million years into an eerie, empty, dying Earth, it’s still a rousing, exciting, and visually splendid take on a seminal work of sci-fi literature.

Village of the Damned (1960)

John Wyndham was one of the most revered British science fiction writers in history, so it’s no surprise that two of his best-known novels made it to the screen—multiple times, in fact—starting with this crisp, haunting chiller based on The Midwich Cuckoos. One day everyone in the small English hamlet of Midwich falls unconscious, awakening to discover that all the women are inexplicably pregnant. The children they give birth to, all on the same day, are possessed of extraordinary powers and clearly not human. They are in fact the vanguard of a subtle alien invasion.

Economically told and quite chilling to this day, Village of the Damned benefits from its tense atmosphere, the eerie look and performances of the children, and the cold ruthlessness with which they begin to exert their control over the town. The ending is powerful as well, with teacher George Sanders planning to kill the children with a bomb as they use telepathy to batter his mental defenses. A 1964 sequel which flipped the premise, Children of the Damned, was less effective but still worthwhile, while John Carpenter’s hopelessly dull 1995 remake of the original remains one of his weakest efforts.

The Day the Earth Caught Fire (1961)

“Chilling” may be an ironic way to describe a movie titled The Day the Earth Caught Fire, but Val Guest’s gritty, semi-realistic sci-fi drama does make the blood run cold. In the movie, an alcoholic journalist for London’s Daily Express stumbles upon the biggest story of his career—that simultaneous nuclear tests by the U.S. and Soviet Union have pushed the Earth off its orbit and sent it hurtling toward the Sun! As catastrophic climate change ensues and civilization breaks down, the governments of the world come up with a Hail Mary plan to detonate four more bombs, in the hope that the blasts shove Earth back into place.

Heavy on character development and realistic depictions of newspaper work (the movie was partially filmed at the real Express offices), while gradually building a sense of doom through modest camera effects and well-placed stock footage, The Day the Earth Caught Fire is one of the finest examples of nuclear age “end of the world” sci-fi of its time. And its ending is still bracing to this day, as the film leaves us before the detonation of the bombs with a shot of two potential newspaper headlines: “World Saved” and “World Doomed,” but doesn’t reveal which one ultimately runs.

Panic in Year Zero! (1962)

Panic in Year Zero! may be one of the first survivalist post-apocalyptic movies. Ray Milland directs and also stars as Harry Baldwin, who sets out from Los Angeles to the Sierra Nevadas with his family for a fishing trip when LA and other major cities are eradicated by atomic bombs. Harry wastes no time finding guns and hiding his family out in a cave, ostensibly to wait out the chaos that follows. But chaos finds them in the form of three hoodlums, who rape Harry’s daughter and another nearby woman before Harry Baldwin deals out the kind of justice that would make Harry Callahan proud.

Like a lot of films of the era, Panic in Year Zero! is cheaply made and seems rushed, especially toward the end, and we don’t really see the full effects of the kind of nuclear attack that the film proposes. But Milland is believably tough as a patriarch turned protector, and the film’s unyielding moral viewpoint must have seemed a bit shocking even back then.

The Day of the Triffids (1963)

Another John Wyndham adaptation here, perhaps of his best-known book, although the Steve Sekely-directed film is not especially faithful to the author’s grim narrative. In the film, a meteor shower leaves most of the world’s population blind and deposits spores on Earth that grow into monstrous, mobile plants called triffids that kill humans. Only Bill Masen (Howard Keel) and a handful of others still have sight as a scientist and his wife race furiously to find a way to reverse the blindness and stop the triffids.

Wyndham’s novel is far more expansive and beyond the reach of this film’s modest budget, but the movie manages a number of chilling moments, and the triffids themselves are effective. Still, the ending (which M. Night Shyamalan borrowed for Signs) is contrived and simplistic, which is why many prefer the 1981 British miniseries based on the book (another arrived in 2009).

X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes (1963)

Ray Milland again, this time in a Roger Corman-directed existential drama as a scientist who discovers a formula which allows him to see through anything. At first the usual shenanigans ensue, as Milland looks through women’s clothes and so forth. But as his vision peers further and further into the universe, and through the fabric of reality itself, his mind is unable to cope with what his eyes show him.

Corman distinguished himself this same decade with the psychosexual subtext of his Edgar Allan Poe horror movies, and here he does sci-fi proud as well with this thought-provoking and increasingly unsettling allegory, featuring a knockout performance from Milland. The ending is as bleak as they come, as Milland takes the Biblical admonishment “if thine eye offends thee, pluck it out” quite literally.

Ikarie XB-1 (1963)

This may be the most obscure title on this list, but in many ways it’s one of the most influential. Based on a novel by Polish sci-fi author Stanislaw Lem (Solaris), this Czechoslovak production from director Jindřich Polák is astoundingly cerebral, literary science fiction that follows a deep space mission to a mysterious planet orbiting Alpha Centauri. Along the way they contend with a dangerous “dark star,” an abandoned Earth ship carrying nuclear weapons, and the breakdown of some of the crew members.

Starkly designed, character-driven, and allegedly viewed by Stanley Kubrick before he made 2001: A Space Odyssey, Ikarie XB-1 was cut by 10 minutes, given a new “twist” ending, and retitled Voyage to the End of the Universe when it was released by American International in the U.S. in 1964. The original has been restored and released on Blu-ray (and can also be found on YouTube), where it will hopefully be rediscovered as one of sci-fi’s finest international offerings.

The Damned (1963)

Directed by American expat Joseph Losey, The Damned begins as a sort of delinquent youth drama before turning into something more unsettling and horrifying: A middle-aged tourist named Simon (Macdonald Carey) begins an affair with a young woman named Joan (Shirley Anne Field) while on vacation, much to the chagrin of her overprotective hoodlum brother King (Oliver Reed). The couple’s attempt to escape King’s wrath leads them to an underground bunker, where a group of children are being held secretly by the government.

An accident has made the children radioactive, but valuable for their ability to survive a nuclear war. It’s hard to tell what’s more disturbing, the plight of the children or the callous disregard with which the government treats them and anyone who comes in contact with them. Filmed in 1961 for Hammer, released in the UK two years later, and not issued in the U.S. until 1965 (renamed These Are The Damned), The Damned may be the most boldly experimental entry on this list.

The Last Man on Earth (1964)

The first of three (and counting) adaptations of Richard Matheson’s landmark novel I Am Legend, The Last Man on Earth was dismissed for many years as a low-budget, inept handling of Matheson’s classic. But the years have been kinder to the movie, and, with its screenplay by Matheson itself, fans have come to realize that it is the most faithful version of the book to date, especially in light of the liberties taken by later remakes The Omega Man (1971) and I Am Legend (2007).

Director Sidney Salkow can’t quite get past the movie’s budgetary constraints, and while star Vincent Price does a good job, as always, there’s a sense that he’s miscast as Robert Morgan (Neville in the novel), the last remaining human in a world overrun by biological vampires. Still, the film does stick pretty closely to the book, has plenty of creepy atmosphere, and was an undeniable influence on George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead four years later.

Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964)

Yes, the title may be silly, but this is more or less a solid sci-fi retelling of the classic Daniel Defoe novel, only now it is an astronaut named Chris “Kit” Draper (Paul Mantee) who finds himself stranded on the red planet with only a monkey for companionship and an occasional hallucinatory visit from his dead crewmate (Adam West!). Draper soon comes across the other inhabitants of Mars, primitive humanoids who are being enslaved by alien beings, and rescues one of them.

Director Byron Haskin, who helmed The War of the Worlds and another film on this list, brings a pulp sci-fi sensibility and great visuals to a rousing space adventure. It’s arguably more fantasy than sci-fi, despite its Martian setting, but it’s fine entertainment either way and a minor classic in its own right (hell, it even got a Criterion Collection release).

The 10th Victim (1965)

Fans of The Hunger Games, The Running Man, and actual real-life reality show contests can trace their lineage all the way back to this Italian sci-fi satire, in which a planet wrecked by World War III tries to prevent World War IV via “The Big Hunt,” a televised pursuit in which contestants must go 10 rounds, five as the hunter and five as the target, in order to win vast amounts of money and celebrity status. Of course the show is the most popular in the world.

Ursula Andress—the original Bond Girl from Dr. No—goes up against Marcello Mastroianni as she vies for a massive corporate sponsorship, and while he just wants to pay his debts. Based on a short story by sci-fi author Robert Sheckley, The 10th Victim may have not aged all too well and suffers from the usual poor dubbing of the time, but as DNA for so many similar stories to come, it’s worth checking out.

Planet of the Vampires (1965)

Directed by Italian horror auteur Mario Bava (Black Sunday), this horror/sci-fi hybrid was an undeniable influence on Alien as well as similar films that followed in the latter’s wake, including Pitch Black, Event Horizon and Prometheus. When two ships on a mission to explore deep space pick up a mysterious signal from an unknown planet, they land on the surface only for the crew of one ship to become possessed by a strange presence and begin killing the others. The force turns out to be the disembodied inhabitants of the planet, who wish to take control of the humans and their ships and head for Earth.

With literally no money to work with, Bava used all his filmmaking genius to create visual effects in camera. He also uses fog and colored lights to gorgeously disguise the threadbare sets, creating plenty of menace and atmosphere with his stylized direction. The result is a film that looks like a sci-fi magazine cover of the 1950s come to life, wielding a strange, surreal power. The scene where the human astronauts come across the remains of an alien vessel that crashed on the planet before them was almost directly transplanted into Alien.

Seconds (1966)

Director John Frankenheimer had an incredible run of classic films in the ‘60s that included The Manchurian Candidate, The Train, and Seven Days in May, but Seconds is in many ways his secret masterpiece. Based on a novel by David Ely, it follows a depressed, middle-aged banker named Arthur Hamilton (John Randolph) who, disillusioned with his life and family, submits to a procedure by a mysterious company in which he is given a completely new appearance, identity, and life. Emerging as an artist named Tony Wilson (Rock Hudson), with a new career out in Malibu, Hamilton soon finds himself gripped by melancholia again—only his options now are not just limited but horrifying.

Hudson is outstanding, stretching himself outside of the romantic comedy roles he’d been known for, and the movie is bolstered by James Wong Howe’s incredible, disorienting black and white cinematography and the usual fantastic Jerry Goldsmith score. But Seconds is also deeply unsettling for its portrayal of a regular human being torn between sticking to his responsibilities or following what he thinks are his dreams—and having no easy way to resolve that tension.

Quatermass and the Pit (1967)

Nigel Kneale was one of the finest writers of filmed and televised sci-fi in British history, and his crowning achievement was no doubt the BBC serials, later adapted as films, starring Professor Bernard Quatermass. Coming a decade-plus after The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and Quatermass 2 (1957), Quatermass and the Pit (aka Five Million Years to Earth) was the most satisfying and expansive of the three, blending science fiction, horror, folklore, and religion into a stunning thriller that stretched back to the origins of humanity while threatening its future.

When an unidentified object is discovered underneath a London subway station, Quatermass (an excellent Andrew Keir) and his associates establish that it’s a long-buried Martian spacecraft, which crashed millions of years ago during an attempt to colonize Earth. When the device is inadvertently reactivated by the military, it resumes its mission by reawakening long dormant Martian genes planted in then-primitive humans, turning them into killing machines intent on wiping out humans lacking the Martian DNA. Eerie from the outset, full of jaw-dropping ideas, and creepy imagery, Quatermass and the Pit is not just one of the best of its decade, but one of the greatest sci-fi films of all time.

Barbarella (1968)

Let’s be clear: director Roger Vadim’s Barbarella is not a particularly good movie, especially when it comes to the script, the direction, and some of the acting. But it’s noteworthy for attempting to bring a classic French comic book character to the screen, its often amazing production design, and for the sheer, unbridled sexual firepower that Jane Fonda brings to the title role.

Fonda smolders her way through the movie with a combination of naiveté and intense carnality, bolstered by her skimpy yet eye-catching costumes. While the film’s sexual politics may be dated, one never gets the feeling that either Fonda or the sweet-natured Barbarella are being exploited. That and the movie’s psychedelic visuals are just enough to keep one intrigued despite the picture’s many other shortcomings. Campy and cheesy, Barbarella is a chore to sit through, an acquired taste, and a basket of pleasure—often all at the same time.

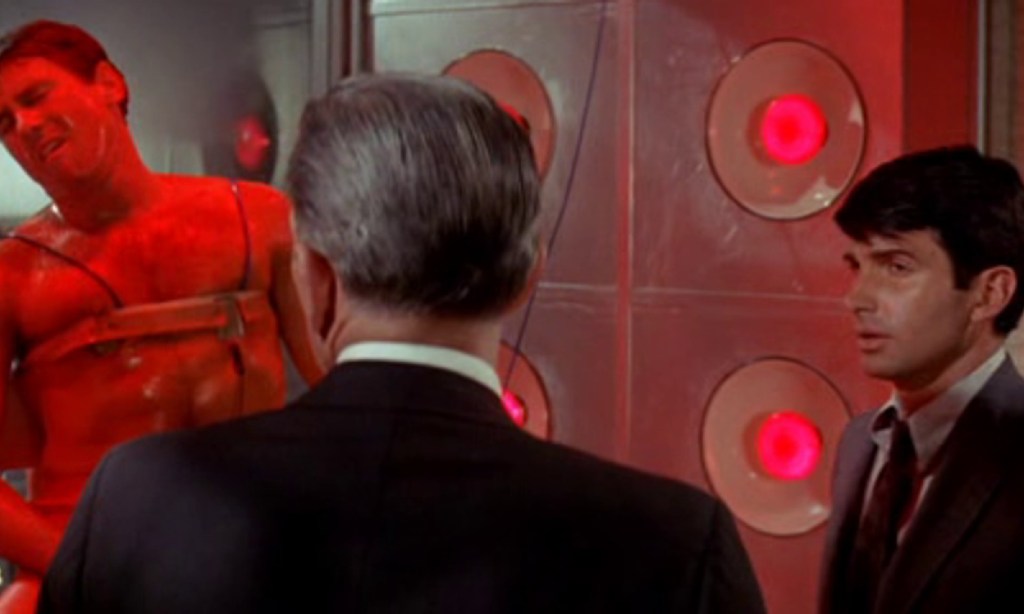

The Power (1968)

The final collaboration of producer George Pal and director Byron Haskin (and the latter’s last film), The Power is a sometimes confusing but also gripping adaptation of a novel by Frank M. Robinson, in which a team of scientists learn that one of their number is secretly a super-being who is using immense telepathic powers to mow them down one by one and preserve his anonymity.

George Hamilton (Dracula in Love at First Bite) stars as Jim Tanner, one of the scientists who finds his own personal and public background eerily erased as he gets closer to discovering the true identity of the mutant, known only as Adam Hart. The script can be hard to follow and the pace slow, but the excellent score by Miklos Rozsa, the creepy ways in which the mutant uses everyday objects to torment people (like pedestrian signs, toys, and even a door that vanishes into a wall), and the concept of a frightening new turn in human evolution make The Power an under-seen little gem.