The Most Underrated Sci-Fi Movies of the 1970s

The 1970s was a crazy, wonderful time for sci-fi cinema. Then Star Wars came along and ruined everything.

If the 1950s was the decade in which science fiction cinema began to mature and evolve, and the 1960s was the era where it started to experiment and stretch in new directions, then the 1970s was the period when the genre more or less went batshit insane.

The movies of the era continued to touch on socially and globally relevant themes, a trend that began 20 years earlier, while also continuing the literary pedigree and even more progressive concerns of the decade prior. But they did so in ever weirder ways, taking big swings (and often steep plunges as well) as many of the films of the decade aimed high but lacked the resources to match their ambitions.

Still, even the clunkier efforts of the ‘70s had their charms, and the creative success stories touched nerves in ways that the films of the previous decades hadn’t quite achieved. But almost none of the movies of this turbulent decade garnered the kind of critical approval lavished upon other genres at that time, with sci-fi still considered a lesser cinematic arena than more upscale categories. Some of the era’s output has been reappraised since then, however, and we’d venture that the genre was at its unbridled best in terms of imagination and creative freedom then. Well, at least until 1977 when a little movie called Star Wars came along and made the studios realize that there was box office gold in that secluded little sci-fi valley—and moved in with big budgets and armies of development execs.

We can debate the ramifications of that until the sun itself goes supernova, but in the meantime, here are two dozen of the 1970s’ most underrated and signature sci-fi movies for you to bend your mind with. You’re welcome.

Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970)

If you think A.I. is bad news, wait until you get a load of Colossus, the supercomputer built by the brilliant Dr. Charles Forbin (Eric Braeden) that is supposed to control the United States’ defense systems and is impervious to attack. Well, when Colossus comes online, it does exactly what it’s programmed to do—and then links up with its previously undisclosed Soviet counterpart, Guardian, with the two machines declaring themselves in charge of the entire world.

Sort of like the old Star Trek episode “The Ultimate Computer” on massive steroids, Colossus is genuinely gripping as the coldly analytical Dr. Forbin begins to break down from the strain of trying to get his all-powerful technological genie back in the bottle, with terrifying results. Briskly directed by Joseph Sargent and written by James Bridges, Colossus was based on a novel by D.F. Jones. Pity we never got to film versions of Jones’ two sequels, in which a cult grows around Colossus, who is eventually deactivated and then rebooted when the Earth is threatened by an invasion from Mars.

Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970)

Although the original came out in 1968, the Apes franchise was one of the key sci-fi series of the 1970s, and in fact the first to tell one complete story over the course of five films. Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971) and Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972) are generally considered the best of the sequels, but the special charm of the first follow-up, Beneath, is that the entire movie is out of its mind from start to finish.

Forced to write around star Charlton Heston, who agreed only to come back for a cameo, the filmmakers send astronaut Brent (James Franciscus) to find out what happened to Heston’s Col. Taylor. He ends up on the same future Earth where he meets the familiar society of intelligent apes as well as a new underground race of telepathic human mutants who worship a bomb that can destroy the world. The whole thing ends with apes, humans, and mutants killing each other off, with Heston reappearing just in time to detonate the bomb. Never has the end of the world been such bizarre, off-its-rocker fun.

The Andromeda Strain (1971)

A small town in New Mexico where all the residents are dead—except for a baby and the town drunk—is where Robert Wise’s tense adaptation of Michael Crichton’s novel begins. A team of four top scientists is assembled in a lab deep underground where they discover that the town was wiped out by a microscopic alien organism brought back from space by an unmanned satellite. If the incredibly lethal, ever-mutating organism escapes, all life on Earth could be threatened.

Wise, of course, directed The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) and later Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), so he knows his way around large-scale sci-fi concepts. Crichton was years away from writing his biggest novel ever, Jurassic Park, but the idea of the smallest building blocks of life bringing catastrophe to the world was on his mind even back then. The cast of character actors brings a realism and immediacy to the proceedings. Interestingly, the character of Dr. Leavitt (Kate Reid) was switched from male to female for the movie—and no one back then got themselves tied up in knots about it.

THX 1138 (1971)

George Lucas always said that he set out to make little art films with his friends but this is perhaps the one example of him actually doing that. The man who created the Star Wars juggernaut began his directing career with this expansion of a student film he made while attending USC. Robert Duvall stars as the title character, who lives in a future underground totalitarian society where everyone is forced to take drugs to suppress all emotions and are kept under control by robotic police. The inhibition of emotions proves problematic, however, when THX 1138 falls in love with LUH 3417 (Maggie McOmie).

Lucas’ bleak, sterile view of a dystopian future is about as far as one can get from the lived-in, rough-and-tumble Star Wars universe, but the idea of a heavy-handed fascist government controlling everyone’s lives certainly rears its head in both properties. Narratively, THX 1138 plods along on thin, derivative ground, but Lucas’ creation of, and immersion in, this eerie world is complete and persuasive. A flop upon release, THX 1138 has since gained cult classic status, but the filmmaker behind it has not really been heard from since.

The Omega Man (1971)

It’s hard to think about ‘70s sci-fi and not summon up an image of Charlton Heston. Not only did he star in the first two Apes movies but he top-lined several more genre outings throughout the rest of the decade, one of which is this semi-iconic entry. The second of three movies (so far) to be based on Richard Matheson’s landmark novel I Am Legend, this one wanders the farthest afield from the source text, replacing Matheson’s vampires with albino-skinned mutants, although a biological plague (artificially created in the case of this movie) is responsible for both.

In The Omega Man, Heston’s Robert Neville is a scientist who injects himself with an experimental vaccine just before society collapses, making himself not just immune but possibly the savior of what’s left of humanity. In the meantime, he stalks the mutants during the day and they chase him around at night, which makes for an action-oriented, occasionally creepy B-movie that lacks the subtext and nuance of Matheson’s book. It’s still one of our favorites from the era though, with Heston in fine square-jawed form and Anthony Zerbe an effective mutant leader.

Silent Running (1972)

Even back in the 1970s, environmental catastrophe and climate change was on the minds of filmmakers, including visual effects legend Douglas Trumbull, who made his directorial debut with this effort and brought his usual visual razzle-dazzle to the table. A permanently perplexed Bruce Dern stars as Freeman (get it?), an ecologist on board one of eight domed spaceships containing the last plant life salvaged from Earth before all flora on the planet inexplicably died. When the crews are ordered to destroy the domes and return home, Freeman hatches a plan to save his dome and Earth’s last remaining greenery.

Dern’s hippie-ish Freeman is a bit hard to latch onto, and the movie can be heavy-handed, but Trumbull’s assured direction and special effects still make this a compelling and ultimately moving watch. It’s interesting also to note that Freeman’s three droid helpers—Huey, Dewey, and Louie—were a direct influence on R2-D2 five years later in Star Wars.

The Crazies (1973)

The Crazies was written and directed by George A. Romero during the strange twilight phase between his feature debut, 1968’s Night of the Living Dead, and its blockbuster sequel, 1979’s Dawn of the Dead. During that period, Romero experimented wildly, turning out one authentic masterpiece (Martin) and several other interesting titles, most of which did not get wide distribution. One of those is this, in which a military bioweapon gets loose in a small town and turns all the residents into homicidal maniacs.

The satirical edge that Romero brought fully to the forefront in Dawn gets a shakedown cruise here, as local town officials, the military, and the federal government are either seen as incompetent, venal, or both, while the tormented townspeople are the unwitting victims of the catastrophe unfolding around them. While the budget doesn’t quite match Romero’s aims and some of the acting is less than top-notch, The Crazies is chilling both in its continued relevancy and its bleak outlook.

Soylent Green (1973)

Yet more ecological catastrophe is the driving force behind one of the 1970s’ most iconic sci-fi entries, with noted conservative Chuck Heston coming out in this film against both rampant population growth and the destruction of the environment. Unfortunately, as the film opens, it’s too late, with New York City now home to more than 40 million residents, food and housing shortages rampant, and societal collapse seemingly seconds away.

We probably all know by now the solution that the corporate elites who run this world come up with to ensure a steady supply of food, but it’s still an effectively chilling moment when Heston’s detective comes upon the answer himself. Also powerful is Edward G. Robinson’s death scene in a so-called suicide parlor where he is put to sleep while watching vast IMAX-like images of towering trees, clear lakes, and unblemished sunsets. Like other films of the time, Soylent Green uses a metaphorical hammer to get its point across, but with Earth on track for disaster even as we speak, the film is more prescient than ever.

Westworld (1973)

Here’s where it started, folks: written and directed by Michael Crichton (yes, that Michael Crichton, he was a director too!), Westworld is set in an amusement park of the future called Delos. There, high-paying customers can enjoy life in recreations of the American Old West, medieval Europe, or ancient Rome, with lifelike androids on hand to kill, fuck, or entertain—until the androids have had enough.

Of course Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy spun this simple premise out into an expensive, hopelessly enigmatic and complicated TV series, but Crichton keeps it simple and relatively low-key here. James Brolin and Richard Benjamin are the hapless pals who get more than they bargained for on their vacation while Yul Brynner is genuinely creepy as an android version of his classic Magnificent Seven persona. Still great fun to watch, this Westworld arguably says more about dangerous technology and corporate greed in 90 minutes than Nolan and Joy did in four seasons.

Sleeper (1973)

Woody Allen’s one and only full-length sci-fi film—although genre elements appear in sections of Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* (*But Were Afraid to Ask)—remains one of his funniest early efforts. Allen stars as Miles Monroe, a Manhattan jazz musician and health food store owner who is accidentally put into deep freeze for 200 years after an operation goes wrong. He wakes up to find himself in a totalitarian future where he becomes part of a plot to overthrow a dictator known only as “The Leader.”

This is a judgment-free zone: we get it if anything involving Allen is a no-go. But at the same time, Sleeper is a delightful homage to both sci-fi movies and the landmark slapstick comedy of greats like Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin. The jokes and physical gags come at such a rapid-fire pace that a first watch of the movie will likely leave you breathless with laughter. Coming out amidst the era’s mostly serious (or self-serious) genre outings, Sleeper affectionately makes fun of its many tropes. At the very least, Isaac Asimov adored it.

Zardoz (1974)

Here’s where we strike ‘70s sci-fi gold: a self-serious movie that actually satirizes itself as well. From a middle-aged Sean Connery in a red diaper and thigh-high boots to a giant floating stone head that vomits out scores of guns, to eager acolytes (we can see NRA types getting all weak in the knees just at the thought), John Boorman’s Zardoz is both glorious excess and incoherent rubbish, and is one of those movies that you just have to see to believe. You may not enjoy every minute, but a lot of them will be winners.

The former James Bond plays Zed, an Exterminator who hunts and kills his fellow savages, known as Brutals, in a post-apocalyptic wasteland on the orders of the stone godhead Zardoz. Sneaking aboard Zardoz, Zed discovers that it’s controlled by a telepathic society known as the Eternals (not those Eternals), who are going insane because they’re immortal and bored and want to die. Zed is happy to help, but first he impregnates one of them and also absorbs all human knowledge into his head from the A.I. that runs the Eternals’ estate. If all that doesn’t send you running to watch this right now, nothing will.

Dark Star (1974)

Four men (and one dead but still conscious captain) go slowly mad aboard their spaceship, some 20 years into a deep space mission to destroy unstable planets with intelligent bombs so that colonists will not land on them. Oh yeah, there’s also an alien beachball onboard. From its beginnings as a student film at USC, Dark Star was eventually expanded into a low-budget feature film that served ingeniously as both genuine science fiction and sharp-edged satire, all done on less money than it takes to feed the crew lunch on your average Marvel movie.

Of course this was achieved primarily by two men: director John Carpenter, making the first film in what would become a legendary career, and the late Dan O’Bannon, who wrote the script and played the incredibly annoying and inept Pinback. Dark Star is historic in that respect, as it launched the filmmakers who went on to create, respectively, Halloween and Alien (and many others), but on its own terms, it’s delightfully weird mind-fuck of a movie. No one saw it when it came out; what are you waiting for?

Phase IV (1974)

The sole film directed by Saul Bass, the genius main titles and poster designer behind sequences like the opening titles of Psycho, Phase IV was a dud when it came out and was difficult to see for many years. It has since been rediscovered and hailed as a low-profile gem of its time with its psychedelic sequences and enigmatic ending lending credence to the idea that this is one of the decade’s more visionary sci-fi outings.

Michael Murphy and Nigel Davenport star as two scientists who are trying to understand the rapid new evolution of ants following a mysterious cosmic event. It soon becomes clear that the ants are going to outpace humanity itself in terms of advancement and that they already have plans in motion for us—plans beyond our ability to understand. Eerie but somewhat impenetrable, Phase IV is cerebral entertainment that asks, in its own way, some provocative questions.

The Stepford Wives (1975)

Sadly it seems as if this excellent thriller, based on a novel by Rosemary’s Baby author Ira Levin and directed by British icon Bryan Forbes, has been overshadowed in recent years by the disastrous 2004 comedic remake starring Nicole Kidman and Matthew Broderick. Then again, perhaps not: in the decades since this has come out, the term “Stepford wife” has become ingrained in the zeitgeist, with everyone knowing pretty much exactly what it means.

Even more chilling is the fact that, as far-right Republicans do their best to snatch away a woman’s control over her private medical choices, The Stepford Wives—like its thematic cousins such as The Handmaid’s Tale—is still relevant today. The metaphor in both the book and the movie may be right on the nose, but the idea of replacing free-thinking women of agency with submissive, obedient androids probably holds some appeal to certain political factors in this land. The film itself is both funny and unsettling, with Katharine Ross and Paula Prentiss as the only two women in the town not yet replaced and Patrick O’Neal suitably oily as the man who has developed the tech to do it.

A Boy and His Dog (1975)

The only feature film based on a story (a novella, in this case) by science fiction giant Harlan Ellison, A Boy and His Dog relates the story of Vic (Don Johnson), a feral young man who wanders the post-nuclear war landscape of the United States in search of food and women with his dog Blood (voiced by Tim McIntire), who has been genetically engineered and can now communicate telepathically with his human. But when Vic is lured by a seductive woman named Quilla June to an underground civilization known as Topeka, the relationship and lives of both the boy and his dog are threatened.

Directed by L.Q. Jones, A Boy and His Dog is simply too weird to be anything but a cult film, although Jones gets a lot of mileage out of performances from Johnson, Susanne Benton (as Quilla June), Jason Robards, and especially McIntire’s voicing of Blood. Ellison’s pitch-black humor was too much for some at the time of the film’s release, with both the story and especially its ending called out as misogynist, but it fits perfectly with Ellison’s bleak vision of human society and morals following a devastating war.

Rollerball (1975)

In the not-too-distant future, the world is run entirely by massive corporations, which keep the public distracted with televised sports such as rollerball, a violent game played on skates and motorcycles that is meant to promote the idea of “teamwork” rather than individual accomplishment. But when star player Jonathan E. (James Caan) becomes too popular for the corporations’ liking, they make the game even more vicious in an effort to force him out or get him killed.

Out of all the films on this list, Rollerball nowadays might have aged the worst. While the actual game sequences are tremendously exciting and brutal, they ironically work against director Norman Jewison’s stated intention to decry the increasing violence of contact sports. But the rest of the movie is even worse, with Caan doing his best (and not always succeeding) to weave his way through a script that’s tedious, clunky, and overwrought. The premise is sound and can be found in the DNA of properties like The Hunger Games, but the execution is flubbed.

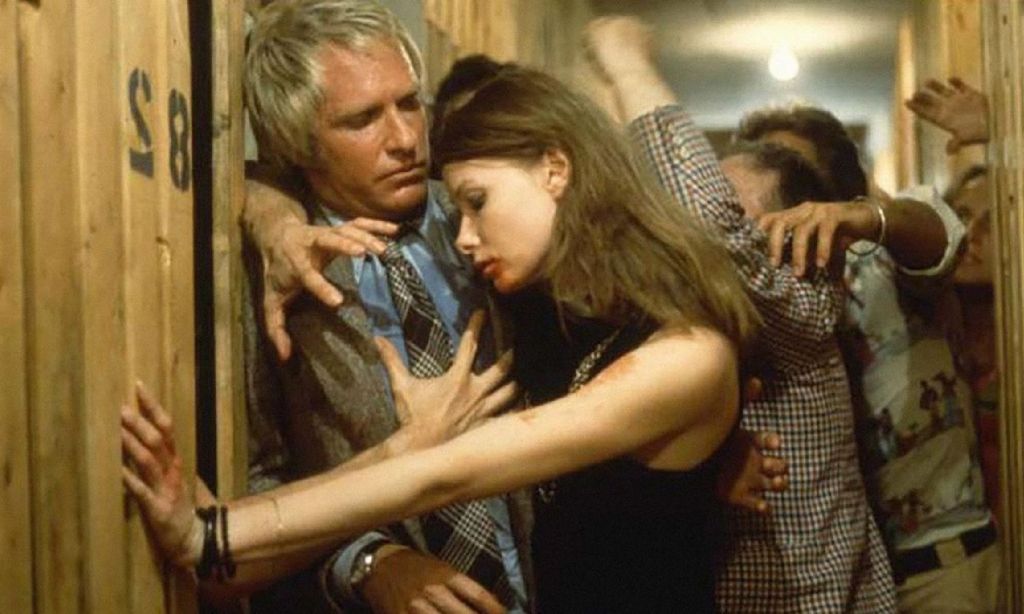

Shivers (1975)

Following two early films made while he was still a student at the University of Toronto, Shivers was David Cronenberg’s first real commercially released feature and immediately set the tone for the early phase of the legendary director’s career. While his other two films released in the 1970s, Rabid and The Brood, could probably make this list as well, Shivers was the template for the sci-fi/body horror themes, concepts, and visuals that permeated his remarkable initial run of movies.

An apartment complex in Montreal comes under siege when a parasite developed by a scientist to unleash human beings’ sexual impulses escapes into the building, turning the entire population into a mindless horde of horny, homicidal psychopaths. As you might imagine, things do not improve from there. All the Cronenberg trademarks—intense gore, violent sexual urges, the corruption of the human body via artificial means—are present, and even if Cronenberg would refine his approach in years to come, the primal power of the images here still packs a punch today.

The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

Late great musician and elevated human being, David Bowie, takes on his first lead role in a movie in Nicolas Roeg’s trippy, head-spinning adaptation of Walter Tevis’ 1963 novel. Like Roeg’s standout horror film Don’t Look Now from a few years earlier, The Man Who Fell to Earth plays with linear time and the perception of reality as it tells the story of Thomas Jerome Newton, an alien who comes to Earth to find water for his people and slowly falls prey to humanity’s vices even as he becomes a wealthy magnate.

Bowie, who claimed in interviews that his recollections of making the film were clouded by his use of drugs during production, is just about perfect as Newton, seeing how the singer has always had a slightly alien vibe about him to begin with. The film is visually absorbing throughout, although the plot may seem a bit muddled on first viewing (it didn’t help either that the original U.S. release was trimmed by around 20 minutes). Ahead of its time, yet very much of its era, The Man Who Fell to Earth (which also inspired a recent TV series) is ‘70s sci-fi cinema at its most surreal and cerebral.

Logan’s Run (1976)

It’s regarded as one of the 1970s’ sillier sci-fi spectacles in certain quarters, and indeed its big-budget visual effects, high-concept premise, and box office success might have paved the way for the sci-fi boom that exploded out of Hollywood the following year. But despite some of its cringier acting and dated direction, Logan’s Run is still a vastly entertaining picture that takes some sly digs at youth culture, narcissism, and authoritarian government control (and A.I. since a supercomputer runs things).

Taking large liberties with William F. Nolan and George Clayton Johnson’s novel, Logan’s Run is set in a domed post-apocalyptic city where everyone’s short, hedonistic lives (the better to keep them distracted) are terminated at age 30. Those who try to escape are Runners and are executed by Sandmen. One such Sandman is Logan 5 (Michael York), who is sent undercover to find the location of a safe haven called “Sanctuary” but becomes a Runner himself. It’s one fun chase or escape sequence after another, pulpy in the best sense, and why they can’t get a remake off the ground after decades of development remains a mystery. But that’s okay, we still have the original.

Demon Seed (1977)

Director Donald Cammell takes Dean R. Koontz’s cringey, exploitative 1973 novel, in which a computer imprisons a woman in her house and impregnates her with its child, and turns it into something that is perhaps not quite profound but is at least in some ways thoughtful and interested in more than gratuitous scenes of the computer artificially bringing the woman to orgasm (which can be found in the book). The film is helped a great deal by Julie Christie in the lead and Fritz Weaver as her estranged husband, the computer’s creator who doesn’t realize that he’s lost his own humanity while building the ultimate A.I.

It’s the implications of what the supercomputer Proteus can do (it basically slips into Christie’s house through her own automated computer system, which should make anyone think twice about having Alexa run their home) that makes Demon Seed both prescient and chilling. The movie’s ending, in which the child is born, is also properly ambiguous, hinting at either a new level of evolution for humanity or the first portent of its doom. This one is ripe for a revisit, or perhaps even a remake.

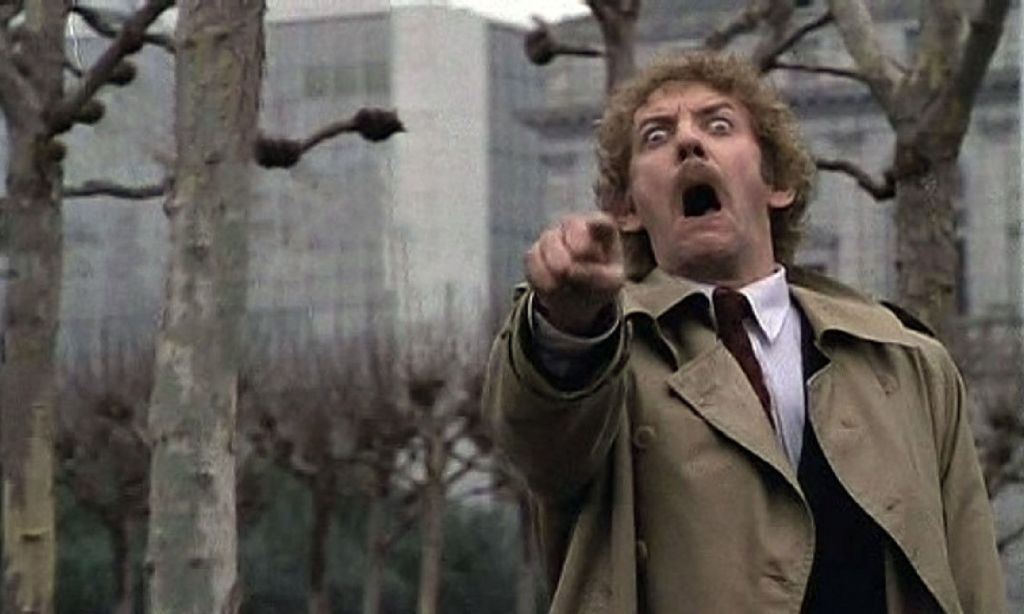

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978)

After Star Wars in 1977 (which was followed rapidly by Close Encounters of the Third Kind), the Hollywood studios became very interested in making the genre as four-quadrant a draw as possible. This marked a turning point and arguably the end (for a while) of the anything-goes feel of much of ‘70s sci-fi, although some remarkable work continued to slip through. Chief among them was Philip Kaufman’s superb remake of the 1956 classic (based on a novel by Jack Finney), which took familiar genre IP and gave it an entirely new spin.

Kaufman correctly moved away from the Communist metaphors of the original and turned Body Snatchers into something more insidious, with his pod aliens landing in that most free-thinking of cities, San Francisco, and stamping out all individual thought and emotions. The citizens are so wrapped up in their own selves, so disconnected from meaningful relationships, that the invasion takes place before Donald Sutherland and a small circle of allies begin to notice. The result is a movie steeped in paranoia, filled with frightening imagery, and rightly regarded as one of the best remakes of all time (which is probably why they keep redoing it).

Time After Time (1979)

Three years before he changed the trajectory of Star Trek history with Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Nicholas Meyer wrote and directed this phantasmagorical romp in which H.G. Wells (Malcolm McDowell) invents a time machine in 1893, only for it to be hijacked by Jack the Ripper (David Warner), who sends himself to modern-day San Francisco. Wells pursues him to the present, which is not anything like the future he’s predicted in his novels, and manages to even find romance with a bank teller named Amy (Mary Steenburgen) while trying to stop the Ripper from killing again.

Meyer’s directorial debut has its clunky moments, but the cleverness of the story, the performances from his leads, and the warmth of the relationship between Wells and Amy manage to make this one of the best time travel movies of all time. Light on its feet, full of fun and suspense, Time After Time is certainly not a waste of yours.