2001: A Space Odyssey – 15 Fascinating Facts

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey changed the face of science fiction cinema.

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey premiered in Washington D.C. on April 2, 1968 and opened in New York and Los Angeles a day later. Four years in the making, Kubrick’s epic spanned all of time and space and spun an awe-inspiring tale of humankind’s evolution from primitive hominid to spacefaring superbeing — and how we were helped along the way by an unseen alien presence beyond our comprehension.

While cinematic science fiction had produced landmark movies in previous years, such as Forbidden Planet, The Day the Earth Stood Still, and the Quatermass trilogy, 2001 elevated the genre in terms of its depiction of the future, its stunning visual effects, and its sheer scope. 2001 ensured that sci-fi would never be dismissed as simple “kiddie fare” ever again, while the movie’s imagery, techniques, and themes have had a lasting impact on the genre and culture in general to this day.

Considering what a timelss classic the film is, we thought we’d provide a quick refresher on some of the interesting and unique aspects of 2001 that make up part of its endlessly intriguing creation and legacy.

1. Kubrick and the Aliens

Stanley Kubrick became interested in the idea of extraterrestrial life after completing his 1964 apocalyptic comedy, Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. As usual with the eccentric and brilliant filmmaker, he began reading everything he could on the subject.

2. Journey Beyond the Stars

His initial title for what became 2001: A Space Odyssey was Journey Beyond the Stars, which he discarded because he thought it sounded like a Roger Corman B-movie title. The eventual title was inspired by Homer’s Odyssey. It was also jokingly called in private, How the Solar System Was Won.

3. Stanley and Arthur: A Match Made in Space

Kubrick reached out to famed science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke to work with him on the project, eventually choosing Clarke’s short story “The Sentinel” as the seed for the film’s themes and concepts. He bought the rights to several other Clarke stories as well to mine them for ideas. Clarke, by all accounts, found Kubrick’s obsessive manner of working both exhilarating and exhausting.

4. Two for the Price of One

It was decided that a screenplay and novel would be written at the same time. Kubrick focused on the screenplay while Clarke primarily penned the novel (both men are credited on the script, while Clarke gets sole credit on the novel). Kubrick’s film ended up more enigmatic and more of a visual experience, while Clarke’s book fleshed out the story and answered more of its questions.

5. Ch-Ch-Ch-Changes

There are some notable differences between the big and the script, such as the destination of the Discovery One mission: in the book the ship heads to Saturn, while in the movie it’s Jupiter. Kubrick changed the planet for the movie because he was dissatisfied with the special effects team’s attempts to visualize the rings of Saturn. The book also contains astronaut Dave Bowman’s (Keir Dullea) final line — “My God, it’s full of stars!” — which was not in the movie 2001 but was heard in the 1984 sequel, 2010.

6. What Does an Alien Look Like?

Kubrick and Clarke asked astronomer Carl Sagan about how to effectively portray the alien race that helps humankind via its monoliths. At first, Kubrick was going to visualize them as humanoid, but Sagan suggested that the aliens would not resemble anything like terrestrial life. In the end, the aliens are never seen, but Kubrick hinted in interviews that they were meant to be a superior intelligence that had evolved beyond physical entities into beings of pure energy.

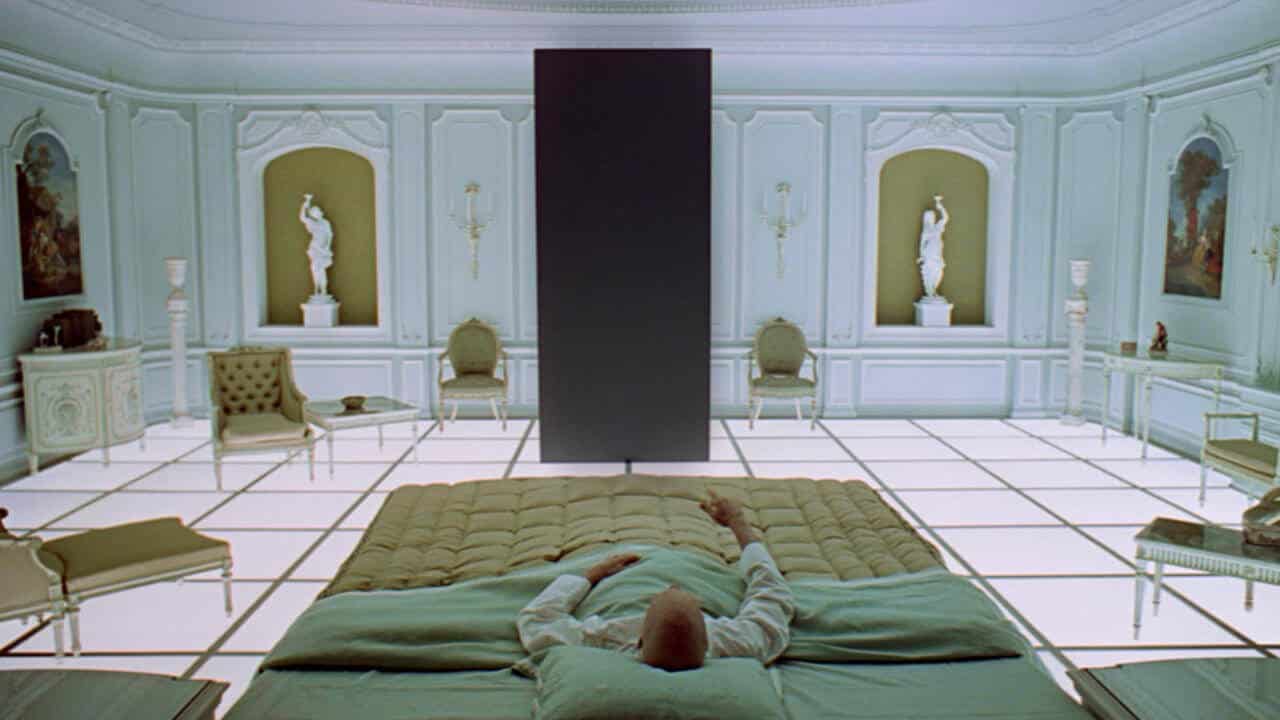

7. The Monolith

Speaking of the monoliths, the original idea called for the mysterious alien object at the beginning of the film to be a viewscreen on which an extraterrestrial demonstrated to primitive humans how to use a tool. That was discarded, although, in the book, the first monolith remains transparent. The monoliths went through a number of changes (they were pyramid-shaped at one point) until Kubrick settled on the flat, solid black rectangular shapes we know so well today.

8. The Lost Prologue

Although Kubrick intended the film to be more mysterious in terms of its plot and meaning, he originally intended to open it with a black-and-white prologue in which various scientists, theologians, and philosophers would discuss the possibility of extraterrestrial life and whether such life may have aided the evolution of humankind at various points in history.

9. Hey, What Happened to My Score?

The now iconic use of classical music throughout the movie — from the opening fanfare of Richard Strauss’s majestic “Also Sprach Zarathustra” to the poetic strains of Johann Strauss II’s “Blue Danube Waltz” during the space docking sequence — was not Kubrick’s first choice. He commissioned an entirely original score for the film from composer Alex North, then decided to drop it in post-production. North did not know his score had been discarded until he saw the film at its premiere.

10. Details, Details

Kubrick, as was his custom, involved himself in every aspect of production — even down to the fabric used for the costumes. He was also meticulous about the design of the spaceships, the visuals for the climactic “Star Gate” sequence, the zero-gravity effects, and more. 2001 also pioneered the use of front projection in the “Dawn of Man” and moonbase sequences.

11. A Spaceship for the Ages

A 55-foot-long model of the movie’s centerpiece spaceship, the Discovery One, was built for the film, along with a smaller 15-foot model for long shots. Many other larger, detailed models of other spacecraft were constructed as well. The Discovery’s command center, a giant centrifuge that rotated to create artificial gravity, was built full-size on a soundstage at MGM-British Studios in Borehamwood, England. It cost $750,000, was 38 feet high, and rotated at three miles an hour.

12. The Nuclear Option

The film was originally supposed to end with Bowman — now transformed into the “Star Child” by the aliens — detonating a string of nuclear weapons in orbit around the Earth. Kubrick decided not to use that ending because he felt he had addressed the nuclear issue in Dr. Strangelove. Clarke kept the ending for his novel.

13. The Space-Based Actor

Actor Gary Lockwood, whose astronaut Frank Poole is murdered by the Discovery’s malfunctioning computer HAL 9000, had appeared two years earlier in the second Star Trek pilot, “Where No Man Has Gone Before.” He played Enterprise helmsman Gary Mitchell, whom Captain Kirk is forced to kill when Mitchell is turned into an insane superbeing by an energy field at the galaxy’s edge.

14. A Slightly Shorter Odyssey

2001: A Space Odyssey premiered in Washington D.C. on April 2, opening a day later in New York and Los Angeles. By the time it expanded to five other cities a week later, Kubrick had removed 19 minutes from the movie, paring it down to its final 139-minute running time. 2001 played for more than a year theatrically, with one theater in Los Angeles showing it in 70-mm Cinerama for 103 weeks.

15. And the Award Goes To…

The film won an Oscar for its visual effects and was nominated for Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Art Direction. Clarke felt it should have won a special Oscar for its ape-man makeup — an honorary award that went instead to Planet of the Apes, released the same year. 2001 also won sci-fi’s highest honor, the Hugo Award, for Best Dramatic Presentation.