Alien and the Movies Inspired by the Ridley Scott Classic

Alien is over 40 years old, yet its influence on film, television, and video games is ubiquitous. Here are some of the greatest projects inspired by the Ridley Scott classic.

If you are artistically inclined, here’s a challenge for you. Design the dining area of a spaceship for a working class, blue-collar crew but, and here’s the catch, it can look nothing like the dining area of the commercial towing vehicle USCSS Nostromo. Let us know how many drafts you get through.

It is a look that is so ubiquitous in spaceship design that we barely even register it anymore, and yet it is also completely distinctive. Whereas before Ridley Scott‘s Alien we had seen spaceships as naval ships, wagon trains, and disheveled VW camper vans, with the Nostromo we were introduced to the spaceship as a long-distance truck, as an ocean tanker, and as an oil rig. And like the titular alien star-beast, once it got through the airlock there was no getting rid of it. Here are some of the best stories to be inspired by, borrow or flat out steal that aesthetic.

Outland (1981)

Sean Connery’s outer space sheriff in Outland works on a mining facility that could have been run by Weyland-Yutani. The aesthetic is immediately recognizable. The corridors, the lighting, even the uniforms fit the style. Corridors that vary between bleached white, floodlit administrative areas and grimy industrial zones. Computer consoles made up of green and black cathode ray tube monitors, and thick, clunky keyboards. Heavy set metal doors. Grilled floors. Exposed, dripping pipework. Extraction fans. You know the drill.

But at the same time Outland shares the dehumanizing quality of the environments in Alien and its best sequels. This mining facility is, to quote Le Corbusier, “a machine for living in,” and humans are only one component of it. It is that dehumanization that Conner fights against in the film.

Moon (2009)

The helium mining facility in Duncan Jones’ Moon could easily share a balance sheet with the mining facility in Outland and the one being dragged back to Earth by the Nostromo. Where Moon differs from Outland is, without putting too fine a point on it, the cleaning. Like Outland, we’ve got plenty of stark white living spaces here, but like Alien, Moon is a bit more realistic about what those places might look like after five minutes. It is full of surfaces that might once have been white, but are now creamy, discolored and stained. The set is littered with post-it notes, bored graffiti and unfinished personal projects.

Alien was not the first film to show us “used” spaceships. Most people’s first exposure to that aesthetic was probably the interior of the Millennium Falcon. But the Millennium Falcon feels like Han Solo’s VW camper van. It is a working vehicle, but it is also a home, built to a human scale. The Nostromo, with its crew of seven, is much bigger than even the starship Enterprise, full of countless labyrinthine hallways, and even it is dwarfed by the enormous mining platform it is tugging back to Earth. The habitable base in Moon is relatively much smaller (apart from that massive cellar nobody likes to talk about), but the human element is dwarfed by the lunar landscape outside.

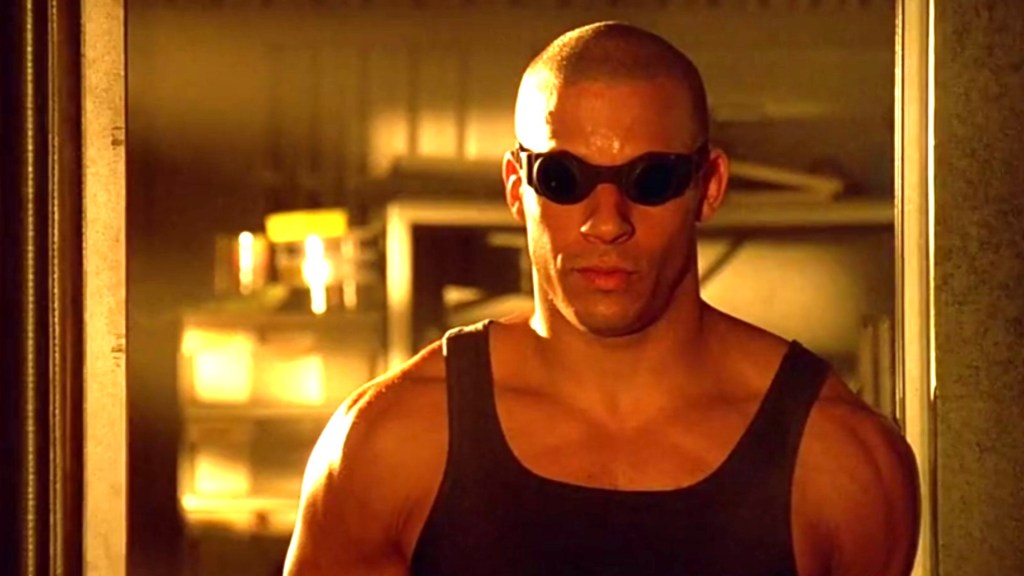

Pitch Black (2000), Riddick (2013)

A bunch of travelers in cryosleep are woken up unexpectedly and then find themselves at the mercy of vicious alien predators (small A, small P). It’s not hard to see the genetic lineage that connects Pitch Black and Alien, and that is definitely there in the aesthetic of the space tech in both this and its threequel, Riddick.

Interestingly, however, the look seems to have skipped over The Chronicles of Riddick. Unlike Pitch Black and Riddick, Chronicles is not a story about fugitives, passenger transports, or bounty hunters. It is a story about empires, armies and space royalty.

If we look for spaceship aesthetics that deviate from the Nostromo pattern, another great place to start is the recent adaptations of Dune and Foundation. Here you will find no exposed wiring or bulky metal furnishings. These ships are sleek, almost organic in their design, in line with the tales of royalty and space empires they portray. But if you want a slightly more subtle deviation from the template, try:

Prometheus (2012), Alien: Covenant (2017)

These films are perhaps the most surprising deviation from Nostromo-chic. Where there are definitely common aesthetic elements between the films, neither Prometheus nor Alien: Covenant feature Alien’s CRTs and clunky keyboards, which are replaced by high-tech holographic displays and those transparent screens everyone thinks are futuristic now, even though they would be a nightmare to use.

And there’s a reason for that. Neither of the ships Prometheus or Covenant is a dirty space tugboat like the Nostromo. Prometheus is a lavishly decked-out research ship funded by a billionaire while Covenant is a colony ship for an ambitious expedition transporting thousands of people. You could even argue that these characters seeing themselves as pioneers and explorers is the reason why they make such poor decisions compared to the truck drivers who are just there for a payday.

Serenity (2005)

Firefly’s nods to Alien are everywhere, to the point where a number of props and user interfaces display the Weyland-Yutani logo. But where it is visibly very different from Alien is in the dining area of Serenity herself. Instead of the kind of mass-product prefab furniture that fits this look, we have wooden, hand-carved-looking furniture. Instead of dirty faded white surfaces, we have flowers painted up the walls. As much as Alien is in the mix, Serenity has more in common with the Millennium Falcon’s VW van aesthetic.

That said, when the series moves to the big screen, we see a Serenity space vessel that is subtly darker and grimier than its TV counterpart, bringing it more in line with the Alien look.

Space Sweepers (2021)

Space Sweepers is set in a world even closer to Alien’s dystopia with skint, indebted space salvagers scraping by in the service of evil mega-corporations, but as this concept art shows, their interiors feel very different from the Nostromo. They are more cluttered, a place where people live rather than rest in cryo-sleep. Paperwork crammed into nooks and crannies, and laundry hanging up wherever there is space, makes this feel more like an actual truck driver’s cab than a spaceship bridge.

This film might be one of the few to pass the “blue collar spaceship but not Nostromo” challenge at the beginning of this article.

Doom (2016)

Not the pretty embarrassing Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson movie, but the videogame, particularly the 2016 version, with its sinister, literally satanic megacorporation and the Hell-powered energy company on Mars. But let’s be honest, we could also put about 90 percent of all space video games in here. From Halo to Dead Space, Gears of War and The Outer Worlds. If you’re on a ruined spaceship with a shotgun barrel nailed to the bottom right of your field of view, the odds are that the spaceship will be clunky, industrial, and by now, frankly, retro.

A big part of it is the fact that Alien is a film that mastered environmental storytelling before video games even had a word for it. One need only look at the legendary Ron Cobb’s “Semiotic Standard,” a beautifully elegant and logically-thought-out series of symbols that can be seen throughout the Nostromo.

It is no coincidence the Alien: Isolation video game of 2014 boasts wonderfully intricate and lived-in spaces that it would be fantastic to wander around and explore if you weren’t constantly on the verge of a panic attack or having a barbed Alien tail burst through your ribcage.

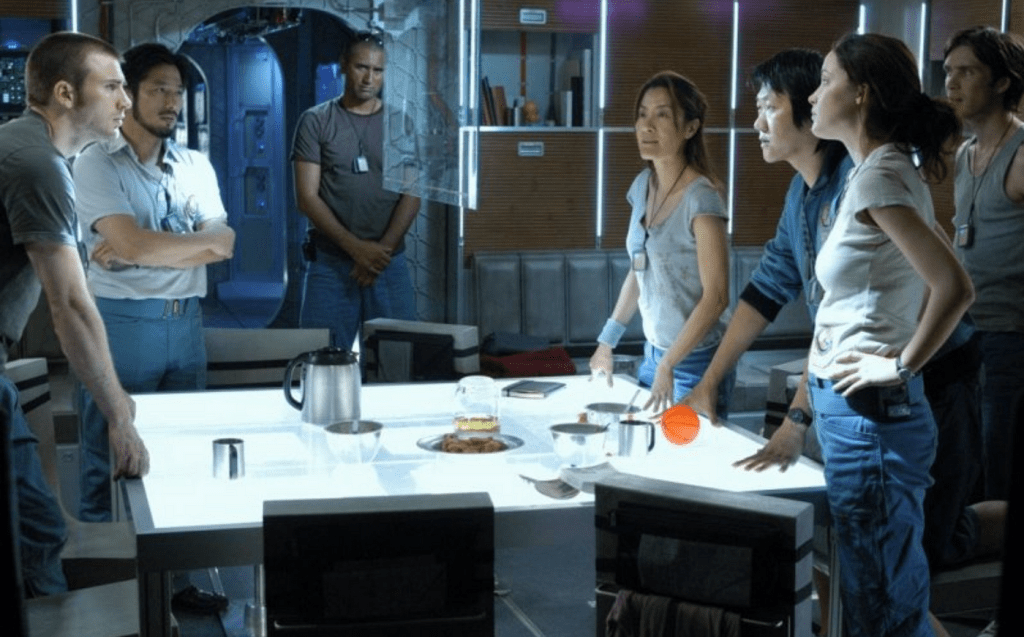

Sunshine (2007)

Sunshine is a great example of a subsection of the Alien aesthetic. Sunshine is probably the most obvious example, although we can also see it in The Martian, or on the Apple TV series For All Mankind. They share Alien’s emphasis on functional design, exposed workings and technology that errs on the recognizable, but everything is also shinier, cleaner and newer. The developers of the upcoming Skyrim-in-space game, Starfield, call this “NASA-punk.” “NASA-punk” is a style that self-consciously aims for realism where your gravity is more likely to be generated by centrifugal rotation than by “gravity plating” or other handwavium, but you are more likely to see touch screens that switches and dials.

However, there is a reason why the clunky, retro interfaces of the Alien universe are so persistent. They remain irritatingly relevant. While you might be viewing this on a flat, HD touch screen on a smartphone or laptop that you’ve long since grown blasé about, it is only recently spaceships have begun to catch up.

For most of the 21st century, the only ways of getting into space have been on board Soyuz capsules dating back to the 1960s, and space shuttles dating back to the ‘80s. Is it any wonder our sci-fi aesthetics confuse “grounded and realistic” with “absurdly retro?”

Red Dwarf (1988-1999)

But perhaps the thing that makes the Nostromo style distinctive isn’t the way rooms are decorated, but which rooms we spend our time in. It is no coincidence that in the challenge at the beginning of this article, the dare is to design a dining area. When we are aboard ships with Nostromo-chic we spend remarkably little time on the bridge or even in the engine room. The first place we go in these ships is to the ship’s mess, the bunk beds (or cryo-bays), and the living spaces.

Red Dwarf drew more directly from Alien than perhaps anyone else, with corridors that could be indistinguishable from the Nostromo, not to mention a captain ripped straight from the colony on LV-426. On Red Dwarf it is rare the chicken soup repairmen characters go to the ship’s bridge or laboratories. Most of the action takes place in the corridors or bunk beds. Perhaps that is why this aesthetic feels so grounded, not because the clunky retro-tech feels realistic for a 23rd-century spaceship, but because we know dining areas, corridors and bunk beds better than control rooms or laboratories.

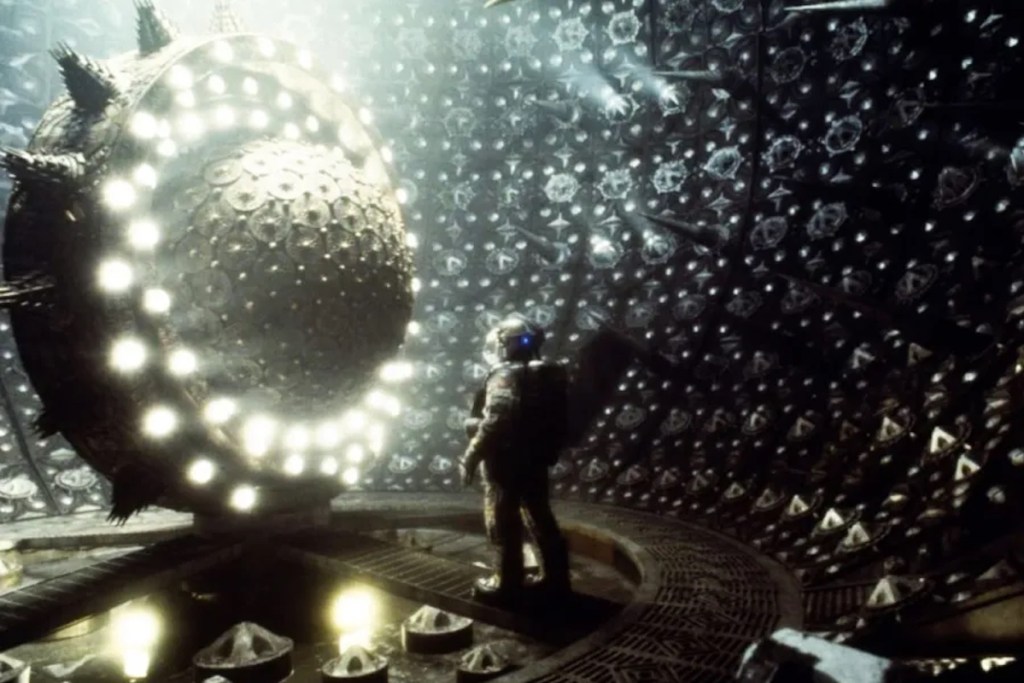

Event Horizon (1997)

Event Horizon’s Lewis & Clark could have easily been the ship that picks up Ripley in the opening scene of Aliens. Event Horizon admirably demonstrates the importance of spaceships that feel lived-in. The difference between the search and rescue ship, Lewis & Clark, and the Event Horizon itself is as stark as the difference between Kansas and Oz.

On board the Clark we go straight from cryo-beds (“Gravity couches” here) to a dining area, just like on board the Nostromo, with bunk beds and stickers on the wall, and every sign of dirty but lived-in workplace mess. On board the Event Horizon, we are moving between bridges, airlocks, laboratories, and of course that fucked up engine room at the end of the corridor of spinning blades. Everything is curves and spikes and things that signal to the viewer that this is not a place where people should go. As industrialized as it looks, it is also as far from the Nostromo look as you can get.

Stories about space travel are about getting as far from home as you possibly can. Perhaps the reason that Nostromo look has persisted so long and so far isn’t how dehumanizing it is, but that while it might not seem like a pleasant place to be, it still feels like home.