Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe Movies Can Still Teach Horror Filmmakers a Few Things

Exclusive: We talk to Roger Corman and filmmaker Chris Alexander about the groundbreaking series of films based on the works of Edgar Allan Poe.

Chris Alexander is nervous. Although he’s known filmmaking legend Roger Corman for 20 years, having interviewed him and engaged with him on a personal level numerous times over two decades, he’s never met the man in person.

“It’s the first time I’m actually going to be sitting down with this man,” Alexander says as we await Corman’s arrival. “I mean, [he’s] my hero.”

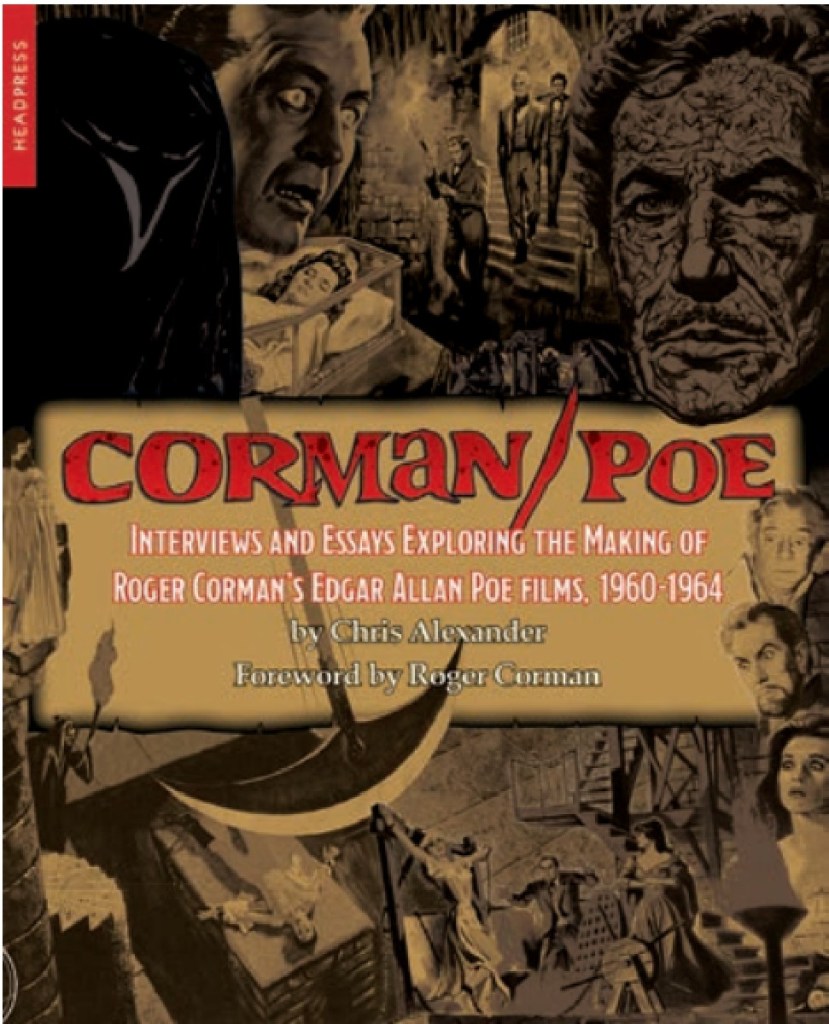

The occasion of this momentous meeting is a signing event at iconic Los Angeles horror bookstore Dark Delicacies for Alexander’s new book, Corman/Poe: Interviews and Essays Exploring the Making of Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe Films, 1960-1964, which is exactly what the title describes: a collection of analytical essays about the entire cycle of Corman’s films based on the works of Edgar Allan Poe, interspersed with interviews about each title with the producer/director.

Starting in 1960 and continuing for the next five years, Corman turned out seven movies adapted from Poe stories (with an eighth, The Haunted Palace, adapted from an H.P. Lovecraft tale but marketed under the Poe banner). Coming at the time when the horror genre was going through remarkable changes and revitalized by different streams of international filmmaking, Corman’s series may well be the most important of their era and a landmark in his own lengthy, fabled career. And their impact on Alexander, who is himself a filmmaker and former editor-in-chief of the legendary Fangoria, is as loud as a raven’s cry.

“They exemplify Roger at the peak of his powers,” Alexander says about the series. “Not just as a craftsman, but as a director, as a student of English literature, as someone who knew how to build a machine and stretch a dime into a dollar, to give you incredible lush production values for very minimal output. It was his way to manipulate a studio system to believe in him and give him complete freedom, more or less, to create the kind of movies he wanted to create.”

It’s a creation that has the stood the test of time as much for its collective beauty as it has its genre indulgences. According to the legendary filmmaker himself, this was by design.

“I was making films that were horror films but with a little bit of a nod to art filmmaking at the same time,” Corman explains when we speak with him shortly after his arrival for the signing (he also penned a foreword for the book). “The themes, the subtext, and so forth could have enabled the films to stand on their own without the horror. They wouldn’t have been as complete [without them].”

Corman cites his source material as the wellspring for the psychologically layered approach to horror that he aimed to achieve with the films. “Poe was an artist,” says Corman. “He was a great writer. With a number of the pictures, particularly The Pit and the Pendulum, the stories were only a few pages long. I was fortunate enough to be working with a very good screenwriter, Dick Matheson, so The Pit and the Pendulum was an example of what we did with a number of films, where we used the short story as the third act. And then we created a first and second act within what we thought was the spirit of Poe.”

Corman’s Road to Edgar Allan Poe

Known as the “King of the B-Movies,” among other things, Roger Corman’s impact on the history of motion pictures is undeniable. Beginning his career in the early 1950s, he largely avoided the major Hollywood studios and worked for smaller companies as an independent filmmaker, turning out movies in all kinds of genres with limited budgets and an incredible knack for stretching limited resources to their fullest.

Along the way he helped launch the careers of filmmakers like Francis Ford Coppola, James Cameron, Joe Dante, Jonathan Demme, Ron Howard, Martin Scorsese, Gale Anne Hurd, Jack Nicholson, Peter Fonda, and scores of others who got their start working on low-budget films under Corman’s supervision. While he largely abandoned directing himself by the ‘70s (with 1990’s Frankenstein Unbound as the one exception), he continues to produce and distribute films.

While Corman directed at least two dozen low-budget genre and exploitation films during the first stage of his career, the Poe cycle, which kicked off with 1960’s The Fall of the House of Usher (aka House of Usher), represented a new phase of filmmaking for the director.

Adapted from the Poe story of the same name by horror/sci-fi author Richard Matheson (whose own literary works included classics like I Am Legend and The Shrinking Man), House of Usher tells the story of Roderick and Madeline Usher, a brother and sister who are the last of their seemingly cursed bloodline who now live out their days in a crumbling, morbid mansion that seems to breathe with the weight of their depraved family history.

Rich with psychological subtext and metaphor, the film was shot in color and made for somewhat more money than Corman had been used to, an opportunity he seized upon to make the film as an almost painterly exercise in Gothic horror and atmosphere.

“I had a great cameraman, Floyd Crosby, who had won the first Academy Award for cinematography,” says Corman. “He had been semi-blacklisted, not fully, but a number of studios wouldn’t work with him. So I was lucky enough to get a brilliant cameraman when he wasn’t working.”

The Poe Films Were the Best of Team Corman

In addition to Crosby, Corman built a creative team that worked consistently with him on the Poe films, starting with production designer Daniel Haller.

“Danny Haller… is one of the great unsung heroes of horror,” Alexander says. “The sets that he built, the production design, it’s just staggering in House of Usher, and even bigger and more larger-than-life in The Pit and the Pendulum.”

Other notable artists who contributed to the Poe movies included Matheson, who wrote Usher, Pit, Tales of Terror, and The Raven, fantasist Charles Beaumont, who penned the screenplays for The Premature Burial and The Haunted Palace, composer Les Baxter (who scored four of the films), and editor Ronald Sinclair. But Corman’s single most recognizable and iconic collaborator on the cycle was undoubtedly Vincent Price.

While Corman assembled impressive casts for the movies–including horror legends like Boris Karloff, Barbara Steele, Hazel Court, Peter Lorre, Basil Rathbone, and Lon Chaney Jr.–it was Price who was the anchor, top-lining seven of the eight films (he was only absent for The Premature Burial, which starred Ray Milland). While the veteran character actor may have garnered a reputation for hamming it up in his long career, which he most assuredly did on occasion, his work on the Poe films is more sublime.

“He was a brilliant, brilliant actor,” says Corman about his star. “I think particularly on the very first one, Usher, he brought a commanding, neurotic presence, which I think fit exactly. He gave a number of brilliant performances. And he could do comedy. In one of the pictures [The Raven] he had a drinking scene with Peter Lorre, and they were partially doing the script and partially improvising. I just let them go, and they were great in that. They were really funny.”

Why Roger Corman’s Poe Films Live On

Coming to a close in 1964 with The Tomb of Ligeia (written by future Chinatown scribe Robert Towne), the Poe movies were remarkable not just for their consistency of style, tone, and atmosphere, but also for their efficiency. Their budgets ranged from $150,000 to $350,000 (more than Corman had worked with beforehand, but still small), and the shoots lasted anywhere from 10 to 15 days.

Yet they hold up incredibly well, and there’s no question that filmmakers today could learn from Corman’s resourcefulness and focused vision.

“They could learn a few things, but the art has moved on so much,” Corman considers. “I think simply from a technical standpoint, the framing, the use of the camera work–I used a lot of foreground composition. For instance, burning candles gave an interesting foreground composition and they blocked out the fact that the sets, particularly on the early ones, weren’t as complete as they should be.”

Chris Alexander is adamant that these 60-plus-year-old films still have a lot to teach both cinephiles and young filmmaking upstarts.

“If you’re a student of film history, these movies are objectively important. It’s inarguable,” he says. “Roger was a trailblazer. The things that he did, the methods in which he worked, the ways in which he cheated his budgets, cheated all his limitations, refused to buckle, these are timeless philosophies. It doesn’t matter what format you’re working on and what era.”

Above all, the movies remain timeless, surreal, eerie, and just finely crafted, grandiose entertainment. “If you are a lover of Roger Corman, these are high marks in his directorial influence, and they’ve stood the test of time as horror films,” adds Alexander before he and Corman adjourn to a private dinner following their book signing. “Of course, they’re magnum opuses, not just because they’re the de facto Vincent Price experience–seven out of eight of them, anyways–but they’re just great movies. Unpretentious, passionate, bizarre, and full of energy and life. They’re just wild movies, man.”

Corman/Poe is available now at bookstores and online outlets from Headpress Books.