Angel Was So Much More Than The “Adult Version” of Buffy the Vampire Slayer

The Angel finale aired 20 years ago. Here's what made the spinoff special.

What do we want from a spinoff? More time with a favorite supporting character, as with Frasier or Better Call Saul? An expansion of a compelling mythos, as with Star Trek: Deep Space Nine or House of the Dragon? Or perhaps a deeper exploration of some potent themes, as with Rugrats offshoot All Grown Up?

Buffy the Vampire Slayer spinoff Angel fulfilled all of those criteria and more.

Premiering in 1999, with its first four seasons running concurrently with Buffy, Angel’s eponymous hero was a reformed vampire, the ex-lover of his parent show’s titular Slayer. The spinoff imported several other characters from Buffy, transplanting them from the small town milieu of Sunnydale to the sinister sprawl of Los Angeles, a darker, more complex setting where demons and vampires rubbed shoulders with high powered lawyers and politicians. It occupied an interesting position in the cultural landscape, airing alongside shows like The Sopranos and The Shield as the more standalone episodic format of syndicated ‘90s TV gave way to the more heavily serialized “prestige TV” era – and like those critically acclaimed shows, it leaned heavily into moral ambiguity.

It’s reductive to call Angel the adult version of Buffy. By the time it reached seasons five and six, Buffy was the adult version of Buffy, and never shied away from complicated issues. But if Buffy’s central metaphor was “high school is hell,” then you could reasonably sum up Angel’s as “leaving high school and making your way alone in the adult world is also hell, but more so.” Which, while less pithy, is unfortunately no less resonant today than it was 20 years ago, when the show’s finale aired.

Feel old yet? That’s ‘cos you are!

What made a weird cult show’s weirder, more cult spin-off such a gem? The key word is “redefinition.”

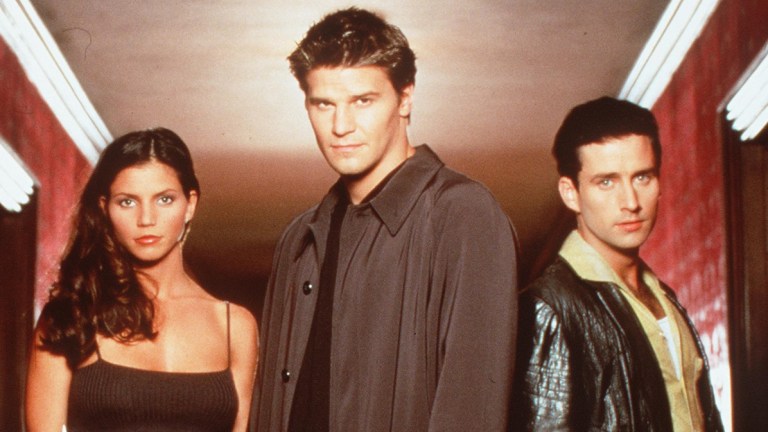

Taking David Boreanaz’s Angel from Mysterious Heartthrob to Troubled Loner

Angel was not, on paper, the most obvious candidate to headline a spinoff. Not because it was particularly revolutionary to build a show around a handsome, taciturn badass who solved crimes and punched people, but because ever since his debut in Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s very first episode, he was almost entirely defined in relation to Buffy.

Whether as a mysterious potential suitor, tragic on-again off-again boyfriend, or murderous antagonist, Angel (David Boreanaz) was compelling, but in a way that was inextricably tied to the Slayer. Divorced from the high drama of their tumultuous relationship, there was no guarantee that audiences would be on board for his solo journey – not least because “immortal former mass murderer” is a slightly less relatable archetype than “struggling high school student.”

The first step was to redefine Angel as a character, reinventing the mysterious heartthrob as a more existentially troubled loner. The seeds for this journey were sown in Buffy season three, with Angel freshly returned from Hell and pondering his place in the world. Angel’s premiere found him alone in a new city, hanging out in dive bars and killing vampires to atone for his past crimes. He even had a cool car.

But from that very first episode, the writers never quite presented Angel as a straightforward hero. Upon killing his first vampires, he savagely rebuffs the gratitude of the humans he’s just saved, almost overwhelmed with temptation at the smell of their blood – a defender of humanity, but by no means part of it. Later in the episode, he heroically leaps into his vintage open-top Plymouth GTX, ready to chase some villains, only to realize that he’s accidentally jumped into the wrong car – the first of many running jokes at the big strapping hero’s expense, including his terrible singing and dancing, his frequent pettiness, and his out-of-touch, old fogeyish tendencies.

As the series progressed, Angel would continue to evolve in unexpected directions. The brooding loner would become the boss of his own detective agency, with a new-found family of Sunnydale alumni. He would turn evil again. He would become a father to Connor (Vincent Kartheiser). The “Shanshu” prophecy would offer a glimpse of salvation, a chance to regain his humanity after serving his purpose – a heroic destiny that would itself be subverted more than once, with Angel coming to realize the fallacy of imagining some cosmic scoreboard, with a final prize waiting once he’d saved his quota of lives. His character and purpose would be redefined right up until the last moments of the show.

And he wasn’t alone.

Helping the Helpless with Charisma Carpenter, Alexis Denisof, Amy Acker & J. August Richards

Most of Angel’s supporting cast, whether imported from Buffy or newly created for the show, would go through similarly tumultuous journeys. Charles Gunn (J. August Richards), while not always best served by the writers, would grow from a fairly one-note street fighter to a more mature, morally conflicted legal pro. Fred Burkle (Amy Acker) would transition from traumatized, stuttering cave dweller to assertive, world-saving physics genius to time-shifting leather clad elder god. Delightfully camp demon Lorne (Andy Hallett), the life and soul of the party, would end the show jaded and compromised, more noir fixer than karaoke bar proprietor. Faith (Eliza Dushku), the rogue vampire slayer first introduced in Buffy, would begin a compelling journey of redemption after a villainous guest spot in Angel season one. Even Doyle (Glenn Quinn), Angel’s – sadly short-lived – first ally, would evolve from a hard-drinking con man to a more heroic figure (his final episode was fittingly called ‘Hero’).

The Angel character with the most pronounced evolution was arguably Wesley Wyndam-Price (Alexis Denisof). Introduced in Buffy as an ineffectual, pratfalling windbag, mostly there to annoy the Slayer, he would ride into Angel season one claiming to be a ‘rogue demon hunter’, though that façade would quickly slip. Over the seasons, Wesley would wrestle with his crippling lack of self-esteem, strongly hinted to be the legacy of childhood abuse, and become much more sympathetic and capable, though that self-actualization was not always positive (men will literally kidnap their friend’s infant son, cut themselves off from everyone they know, start sleeping with the enemy, keep collapsible swords and guns up their sleeves and imprison women in closets with only a bucket for company, rather than go to therapy). By the end of the show, Wesley was functionally unrecognizable, a character arc that nobody could have predicted based on his first appearance.

Which brings us to Cordelia Chase (Charisma Carpenter). It’s difficult to discuss her character without addressing some unsavory behind-the-scenes details – actress Charisma Carpenter has been open about the poor treatment she endured on the set of Angel, much of it from series creator Joss Whedon. Her much maligned season four arc, built around a mystical pregnancy, takes on an particularly distasteful resonance knowing that Whedon was reportedly furious about Carpenter’s real-life pregnancy, subsequently writing her out of the show in fairly undignified fashion. And even when she came back for a triumphant guest spot in season five, Whedon opted to kill her off, something the actress specifically requested he not do.

All of which leaves an unfortunately sour taste, because Cordelia’s arc remains fascinating, and Carpenter navigated the sometimes problematic writing with aplomb. From the vapid, self-absorbed rich girl of Buffy’s early seasons to the less vapid but still self-absorbed struggling actress of Angel season one, to the capable fighter and selfless hero of later seasons, Cordelia was another (mostly) excellent example of Angel’s capacity for reinvention.

But the show wouldn’t just redefine its characters – it would do the same with the Buffyverse itself.

Wolfram & Hart and the Senior Partners

As Buffy went on, the walls between everyday life and the world of magic became more porous, but Angel delighted in tearing those walls down entirely. Lorne’s karaoke bar catered to humans, vampires, and demons alike, with a protection spell in place to discourage fighting. Demons, who were mostly presented as irredeemable monsters in Buffy, became more nuanced, with many seeming like regular Joes trying to make their way quietly in the city.

And then there was Wolfram & Hart. Introduced in the series premiere as a full service law firm catering specifically to evil and demonic clients, Wolfram & Hart would be a recurring antagonist throughout the show, and the basis of one of its most potent themes – that of institutional evil. In broad daylight, the firm would help rich vampires, extra-dimensional demons, criminal gangs and even elected officials go about their villainous business unimpeded, with Angel nearly driving himself and his team mad trying to defeat them.

But, as recurring W&H flunky Holland Manners (Sam Anderson) memorably stated in season two’s “Reprise:” “Our firm has always been here. In one form or another. The Inquisition. The Khmer Rouge. We were there when the very first cave man clubbed his neighbor … the world doesn’t work in spite of evil, Angel. It works with us. It works because of us.”

How could a lone champion and his ragtag crew go up against such bottomless power? This would become a key existential question for Angel as he continuously weighed up the efficacy of his heroism, and the answer that came in the show’s final season was quietly radical.

Exhilarating Series Finale “Not Fade Away”

At the end of season four, Angel was offered a deal – total control over the LA branch of Wolfram & Hart, with all the money, resources and power that came with it, to do with as he pleased. The main throughline of season five thus became the gang trying to maintain their integrity as cogs in this vast machine, having spent four seasons as scrappy underdogs battling overwhelming odds. Could such ancient, institutional evil be put to good moral use? Could such an instrument of suffering ever be reconfigured to alleviate suffering?

To (perhaps pretentiously) paraphrase Audre Lorde: can the master’s tools ever dismantle the master’s house?

The answer the show eventually came down upon was a resounding no. The machine was too big, too complex, too evil. So after some heavy losses, Angel opted to tear the whole thing down, directly provoking the never seen, vaguely Lovecraftian “Senior Partners,” who responded by unleashing Armageddon. And in the show’s closing moments, backs literally against the wall, Angel stared down the apocalyptic horde, raised his sword and said “let’s go to work.”

Cut to black.

While arguably one of the most exhilarating endings in TV history, it’s also in some ways astoundingly bleak. The machinations of Wolfram & Hart are tied very explicitly to those of capitalism – the firm represents U.S. senators and other very human corporate interests, as well as vampires and demons, and Angel and co are told that they need to keep the business running in order to maintain access to its resources. And the show tells us in no uncertain terms that this system cannot be fixed. It cannot be reformed. People can reform – Angel himself is a case study in that respect, though there are limits there too, as illustrated by the arcs of scheming ex-lawyer Lindsey McDonald (Christian Kane) and Angel’s tragic paramour Darla (Julie Benz).

The system, however, will continue to chew people up and spit them out, either compromised or dead. Redefinition has its limits, and the only option left is to revolt, and very possibly die trying. It’s interesting to compare this to another concurrent show, The West Wing, which invested so heavily in bipartisan compromise as a political solution. For Angel, bipartisan compromise meant death, either through brutal violence, or the slow and steady rotting of the soul.

Throughout Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the gang faced some steep odds. There was grief, there was loss. But good always triumphed eventually. The arc of that show’s moral universe bent towards justice – the final shot of the final episode was a slow zoom on Buffy, surveying the site of her latest, greatest victory, smiling as the sun rises. It was a good ending – cathartic, satisfying, mythic.

But contrast it with Angel’s final shot. Angel, bloodied and soaking wet, in blackest night, with a handful of allies, some of whom could barely stand. Fighting until their last breath, which was more than likely imminent.

Because it was never about victory. You don’t fight the good fight because you expect it to end – but neither do you give up. You continue to fight because that’s the only moral choice.

Because “if nothing we do matters, the only thing that matters is what we do.”