The Karate Kid Part III We’ll Never See

Cobra Kai Season 4 conjures The Karate Kid Part III, but franchise creator Robert Mark Kamen had radically different plans for that film.

Cobra Kai continues to effectively mine the long-dormant characters and continuity of The Karate Kid film franchise. The strategy has yielded a successful series that basks in the built-in nostalgia of those old enough to recall the films’ heyday, and even fosters a new generation of fandom. However, the show’s fourth season taps into 1989’s The Karate Kid Part III with the heralded return of villain Terry Silver—a controversial callback, seeing as that film remains widely maligned. Interestingly, a radically different third entry was originally envisioned, one that would have taken the trilogy into time-travel territory.

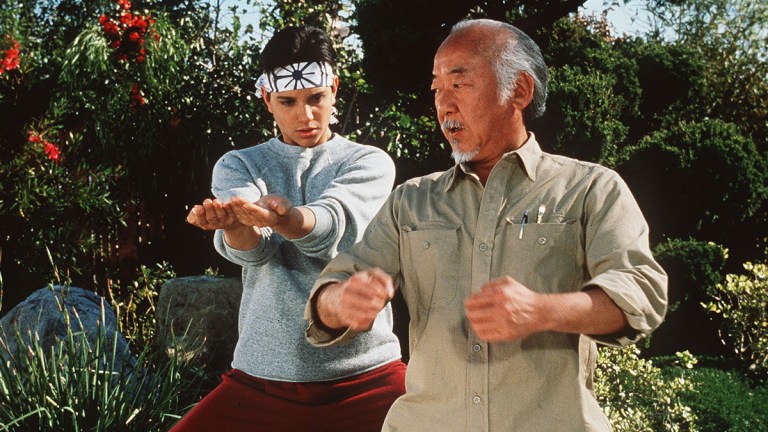

If the teasers for Cobra Kai Season 4, which ominously tout Silver’s return—made 32 years later by Thomas Ian Griffith—left you in need of context regarding its importance, you were hardly alone. After all, the film, in which Silver served as main villain, was a dud, and the least-watched of the original Karate Kid Trilogy. One could fault that failure to a hopeless summer 1989 box office battle against iconic competition from Batman and Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, and momentum drained by lingering money-makers Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade and Ghostbusters II. Yet, Part III was also branded as an uninspired retread of the original, which made it missable. However, franchise creator Robert Mark Kamen, who wrote the entire trilogy, initially pitched it as a prequel of sorts in which Daniel LaRusso and Mr. Miyagi are—in a surprising supernatural twist for a reality-grounded franchise—whisked back to 16th century China, immersed in a tale centered on the origins of Miyagi-Do karate.

“I [initially] turned down doing Karate Kid III because I wanted to do something different,” revealed Kamen in a 2012 interview with Crave Online. “I wanted to have them flash back to 16th century China and do a historical flying people movie. I wanted to do a Hong Kong Kung Fu movie.”

Contextually, the seemingly-incompatible pairing of the intrinsically-Japanese martial art of karate and air-whirling wuxia genre kung-fu films stems back to exposition from 1984’s The Karate Kid, in which Miyagi explains (factually) to Daniel how karate came from China in the 16th century; a tale that was expounded in 1986’s The Karate Kid Part II, in which Miyagi further reveals how Miyagi-Do, specifically, was the result of an accidental Okinawan fishing trip in 1625, in which his ancestor, Shimpo, fell asleep as his boat drifted to the coast of China. There, he would start a family and learn the defense-centric martial art that would become Miyagi-Do. Thus, it would appear that Kamen had designs to have the backstory foreshadow what would have been lofty plans for the third film.

“I was going to tell the saga in reverse,” he further explained of his intended poetic plot parallels. “Daniel and Mr. Miyagi are in a boat. It all happens when Daniel gets hit on the head and he has a dream. He’s in a coma or something and they see a boat in the mist. It docks and Mr. Miyagi and Daniel follow the first Miyagi ancestor into China and then they get involved in this thing.”

So, why didn’t we get this ambitious, intriguingly chaotic version of The Karate Kid Part III? Well, as Kamen stated simply, “It would’ve been really cool, but nobody wanted to do it.” Indeed, the price tag for such a fantastical tale would have been enormous, making it a non-starter. Indicatively, Part III would showcase a noticeable decline in presentation, which was substantially less elaborate than the Okinawa-set Part II, which had effectively used Hawaii as a visually-stunning domestic substitute for the southern Japanese island prefecture. It seemed like an odd development at the time, seeing as the 1986 sequel grossed $115 million worldwide (making it the highest-grossing Karate Kid trilogy film), and represented an upward trend from the $91.1 million made by the 1984 original. However, the franchise’s pop culture impact did not initially yield real bankability, and the studio bigwigs clearly felt that corners needed to be cut for the nevertheless-inevitable threequel.

“Guy McElwaine [president of Columbia Pictures at the time], rest his soul, refused to do it. He wouldn’t do it. [Producer] Jerry [Weintraub] wouldn’t do it,” recalled Kamen of the studio’s resistance to his idea, and his culminating capitulation. “They didn’t want to mess with the franchise and I felt very strongly that doing the same story all over again was f**king boring, so I didn’t do it and they hired somebody else to do a draft. Somebody else could not write Mr. Miyagi and Daniel, couldn’t write them. So, Dawn Steel took over the studio from Guy McElwaine and she was a good friend of mine. She said, ‘How much would it take for you to do what they want to do?’ I was very flippant and I threw a number out and she said okay. I didn’t really want to do that one, but I ended up doing it because first of all, they appealed to me. They said, ‘What, do you want somebody to f**k up Mr. Miyagi? Because we’re going to make the film.'”

With Part III having ultimately reset things back to the original film’s San Fernando Valley backdrop, studio Columbia Pictures had seemingly opted for the safe strategy of reusing a tried-and-true formula—right down to the shooting locations and even the climactic All-Valley Tournament itself. Yet, to its arguable detriment, this approach also reversed any character growth achieved by Ralph Macchio’s Daniel by revisiting the first film’s bullying tropes as wealthy industrialist Terry Silver—on behalf of his old war buddy, Martin Kove’s John Kreese—maniacally wove a web of psychological torture, aided by the brute strength of hired tournament ringer Mike Barnes (Sean Kanan), for stakes that seemed played-out even by that point in the continuity. Ironically, the move yielded an anemic $38.9 million box office performance, which would stand as a franchise nadir until 1994’s Hilary Swank-starring fourth film, The Next Karate Kid, which only made $15.8 million—a failure from which Kamen can distance himself, seeing as he opted not to return for that entry.

Interestingly, while The Karate Kid franchise would never get to fly its proverbial freak flag with gravity-defying big screen time travel travails, it was able to go supernatural in animated form in the fall of 1989 for a similarly-titled NBC Saturday morning cartoon series centered on the further adventures of Daniel and Miyagi. Pertinently, the series saw the cinematic duo—joined by a young Okinawan girl named Taki—travel around the world to recover a lost Okinawan shrine that possesses myriad mystical powers, notably exemplified in the first episode, in which a belligerent Amazon tribal chief uses it to transform himself into a jaguar, forcing Daniel and Miyagi into awkward cross-species combat. So, yeah, it was that kind of show. However, The Karate Kid animated series had only manifested from a 13-episode order, and would not be renewed, leaving a 29-year gap until Cobra Kai brought the franchise back to television properly in 2018.

Lost wire-flying, time-traveling kung-fu opportunities aside, Cobra Kai Season 4 hits Netflix on Friday, December 31, on which it will characteristically strike first and strike hard with no mercy on your New Year’s Eve plans. That’s a good thing, especially since the advance-ordered Cobra Kai Season 5 has already wrapped, and will likely follow up your binge session sooner, rather than later.