John Lewis: Good Trouble – Documentary Spurs Viewers to Action

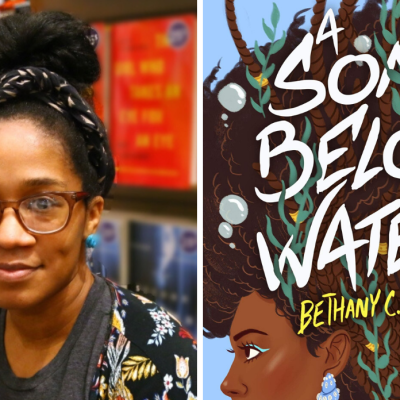

Producer Erika Alexander reflects on the themes of John Lewis: Good Trouble and the legacy of the legendary Civil Rights icon.

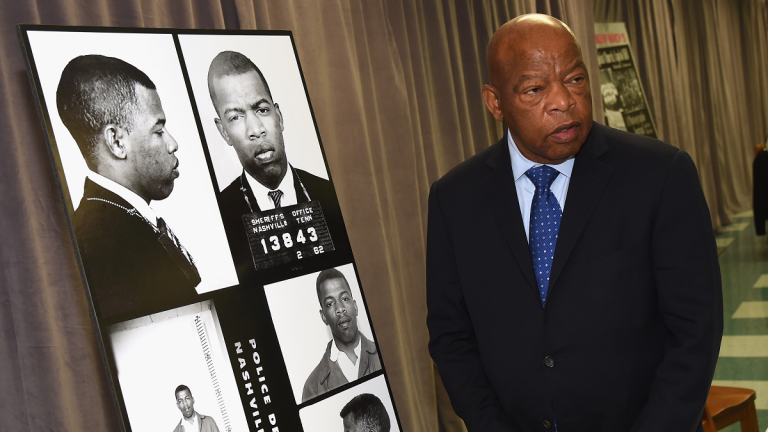

Congressman John Lewis is one the central figures in the early struggles of the American Civil Rights Movement that included bloody confrontations with white policemen, sit-ins, boycotts, widespread lynching of Black people, assassinations of prominent leaders, and culminating with marches in Selma, AL, and Washington, D.C. Lewis is now the subject of John Lewis: Good Trouble, a comprehensive new documentary directed by Dawn Porter.

John Lewis: Good Trouble is an alternately impressive, shocking, enraging, and motivating film that calls on everyone to do better in life. John Lewis is a legend, an icon, and an American pioneer. The combination of historical footage, interviews with family, friends, and colleagues, and trailing Mr. Lewis is a great balance over the span of the film. The film triggered suppressed feelings that welled up in me as a Black man who was raised in segregated Houston, who traveled across town under the cover of dawn to a predominately white magnet school where I first experienced passive-aggressive racism. America is still dealing with white supremacy, oppression, police brutality, and police murders of yore.

Regardless of political affiliation, sensible viewers will hopefully broaden their local and national view after watching the Good Trouble documentary which could compel its audience to explore real world solutions on how and where they can make a difference socially and politically.

The subtle and obvious dare inherent in Good Trouble is taking the baton for the next leg of the race that our Black forefathers and mothers began years ago. Will you dare take up the mantle for new leadership? How does one peacefully protest and remain alive? How does one practice nonviolence and not become enraged? Watch the film and cobble together answers for yourself.

We spoke with Erika Alexander, actress and producer, most notably for her roles on Living Single and Black Lightning, about producing John Lewis: Good Trouble, the living legacy of Congressman Lewis, and how Americans must acknowledge the country’s painful history and discover ways to get into their own brand of trouble to ensure equality for all.

Den of Geek: What drew you to the documentary?

Erika Alexander: I have been inside of politics as a surrogate since 2007. I’m Hillary Clinton’s most traveled surrogate, and I got to campaign in Georgia with Congressman Lewis, Stacey Abrams, and Ayanna Pressley in 2016, because I stayed her surrogate throughout her first and second run. Together, all of us went around Georgia to campaign, but we also got a chance to see how Congressman Lewis does it. It was truly a masterclass. At the time, I had no idea that Stacey Abrams and Ayanna Pressley would come to the national fore as they did, but we all knew who John Lewis was.

So the fact that we were able to work with him in that way, and also eventually, got to know people in his office, specifically Rachelle O’Neil, the constituent services representative, and we became friends. She was my conduit to the congressman for the film. Another friend introduced me and my partner, Ben Arnon, to Dawn Porter and her producing partner, Laura Michalchyshyn, who just happened to be making a movie about John Lewis. And so we decided to partner together to make one and that’s John Lewis: Good Trouble.

Were you around during the filming, editing, or post production for the documentary?

I was around for the filming. Not a lot of filming that went to Georgia. Not Georgia, but you know, like to [Lewis’] home and things like that. But especially in DC, New York, and those places, because the people we asked to participate from Hillary to President Clinton, to Ayanna, to Sheila Jackson Lee, those are all my friends.

And by the way, [Lewis] would need me to make the introduction. The truth is they needed somebody who they trusted in order to feel like they were being handled by a group of professionals. I was able to facilitate all of those interviews. That’s no small thing in documentary terms.

Do you think of the congressman as a hero, an icon, or a legacy?

He’s all of those, and he’s earned it the hard way. I mean, we all talk about good trouble and being a moniker and the icon status, but the truth is he’s committed his life to the fight for Civil Rights and justice for all, and he did it armed with just the courage of his convictions and inviting philosophy of nonviolence and peaceful protest. He calls it his work for the beloved community, and that’s what Martin Luther King and others were fighting for.

But he was trained in this. Dawn loves to say that this didn’t happen by happenstance. He’s not just brave. He was trained. They approached it from an intellectual point of view. James Lawson taught him about nonviolence. The idea of nonviolence as a weapon was a methodology. He is a political genius, and so we honor him in that way.

Have you always wanted to be a producer?

(laughs) Yes. I just didn’t know it. Now, here’s the thing. I’ve been in Hollywood for 37 years. And the thing that you find out is that the people who have more power than the actors are the writers, creators, and producers. Directors at some point, but they need those other people in order to do their job. So I knew I wanted to be a producer. I just knew I wanted to write and be more in charge of my own destiny.

Read more

There were very few options for a person of color, especially a Black woman in 1984, when I got my first SAG card until now. When I first entered the scene, there was no Viola Davis, Nia Long, or Jada Pinkett-Smith, but there was Cicely Tyson and Lorraine Toussaint.

I like to say that I saw that producing would be the best advantage I had to creating more opportunity for myself. Turns out that as I got to be older and saw that there were much more systemic challenges inside of the paradigm that I had to find a way to be a producer in order to create the pathway to do the things that I wanted to do.

That sounds like a political statement, or a political stance. What lessons have you learned from John Lewis’ life? Are you saying to enact change you had to embrace politics?

Yes, absolutely. Absolutely. I think that we all bring ourselves to our projects. My father was an itinerant preacher, and my mother was a teacher. Both my parents were orphans. They always had to create and make their way. I think I saw very quickly that the society, the social contract that we all make with each other, can be a one-way street a lot of times. You want to create a two-lane highway on the gravel road. That means you need to bring some cement, you know? (laughs)

That’s power when you start to build things. And I got to give y’all props, writers, journalists, media people, because the thing that focuses us are the stories we tell. When we start to bring that power to change the narrative that has been told about us, the lie all these years, we can stop the George Floyds from being executed in broad daylight.

Do you believe the documentary will change opinions, open minds, for those who still haven’t accepted the importance of civil and voting rights?

I hope so. I think the mindset wants to change, or is looking for a little opening, or a reason why. It’d be up to them.

There’s some people that are hard of hearing, and then there are those who are hard of thinking. They don’t know how to have discernment. They just know that they feel like they’re being attacked and they like that narrative. So they’re not willing to let others in, however for people who are ready for change, it will find them.

One thing that struck me, the parallels from his early years to what’s happening right now.

Amazing. Right?

America hasn’t learned after 450-plus years. Contrasting voices and viewpoints have emerged since the start of the Civil Rights Movement. One of many topics lately is how to be an antiracist among the different schools of thought. Black people aren’t a monolith, however, we need a united voice, which we still don’t have.

Well, the old folks said there was nothing new under the sun. We are always fighting the same things, and having the same conversations. If you look at some of the philosophers and things they talked about, it’s why it resonates with us because it’s what we’re going through now.

I can’t guarantee what the future would be, but I know I can be better. That’s what I need. So if I’ll be better and everyone else thinks they can be better, whether it’s around civil rights, environment, civil justice, social justice, immediate sort of restitution and reparation. That means that you’re creating a better world in real time. It’s not because anything’s changed. It’s because we’ve changed that things change. Oh, that’s some deep shit! (laughs)

One of the many quotes that stuck out to me is when he says, “When you lose the sense of fear, you are free.”

That’s real.

If we’re using that as a basis, there are too many of us who are afraid.

Yes. For all sorts of reasons, afraid to lose, afraid to lose what we have, afraid that the sacrifice would be too good, afraid that it doesn’t matter anyway. We tried. Afraid that somebody’s going to take what you have. If you can cage children at the border thinking they got something you want, then you are terrified of the future and the future isn’t in their stars. It’s in yours. Who you are right now makes their future more certain that your future in your current state of your status is assured and more importantly elevated. So I don’t know. Yeah, you’re right.

I recently confided in a friend that I think I’m in mourning.

Mourning. Wow.

We all make plans, and those I might’ve had in February didn’t come to fruition. I think we’re all in a long mourning process, and will be for the foreseeable future.

That’s just it, we’re looking in the wrong direction. Our direction is where John Lewis is looking and where MLK, Malcolm, Baldwin, Maya, and Fannie Lou Hamer were looking. They look toward a future that wasn’t presented to them. They looked at one that they made, the one behind their eyes. There’s no reason for Black people to stand around talking about hope when what they see in the real world serves them less than anyone on this planet.

But that’s what makes us so miraculous is that we have been sort of pulled into a real dark struggle. It’s worthy of Lord of the Rings. We are Frodo going across to Mordor. You hear me? Toss that rock into the fiery hell it came from, and each person who gets that ring thinks they have power.

We can replace even white power with a different set of power. It’d be the same thing we’re fighting. We just got to keep knowing that Middle Earth, it’s not just a journey and a destination. It’s what each person has to do. It’s their leg of the race. So this is our leg.

I agree. Are we more determined to vote with the way things are in the world now?

I don’t know. Freud talked about a death instinct that people have. An instinct to want to tear things down when things are going well. Think about the Obama years and how he got the country back, and everybody thought there was a new energy with his black face and his very sort of “aaaah” new thing (gestures razzle-dazzle showman’s hands). And then they tore it down.

Here’s the other thing they could tear down, even inside a pandemic. They could look at this and say, fuck it. Let’s all go in on this. And I’m not voting for this and I’m not voting for that. We are just going to go hard. What they don’t understand is that they ceded their right to have the conversation. Whoever’s in control that shows up to vote, they get it. They didn’t understand that, otherwise they would have been in local politics and wouldn’t be so up about who was president.

If you don’t care about who’s running your neighborhood, you don’t give a damn about who’s at the top. I’ll see. We’ll see. I think people are frightened, but you wouldn’t be surprised to know that fear runs concurrently against hope.

That’s why his quote stuck out. We’ve moved into the realm of white fragility, books, and how to not to offend people of color.

It has to be taught, because one of the things about racism we know is that in his book, Baldwin said, it’s an illness, it’s passed on to people and they don’t even have the vocabulary. The fact that they want to talk about how they might have an issue, and that it’s inherent inside of how they’ve learned things. They need to look and say, “wait a minute, I might just be totally fucked up.” Yes, you are. If you start from there and you relearn things, then suddenly we can have a conversation again that benefits them more than it benefits us.