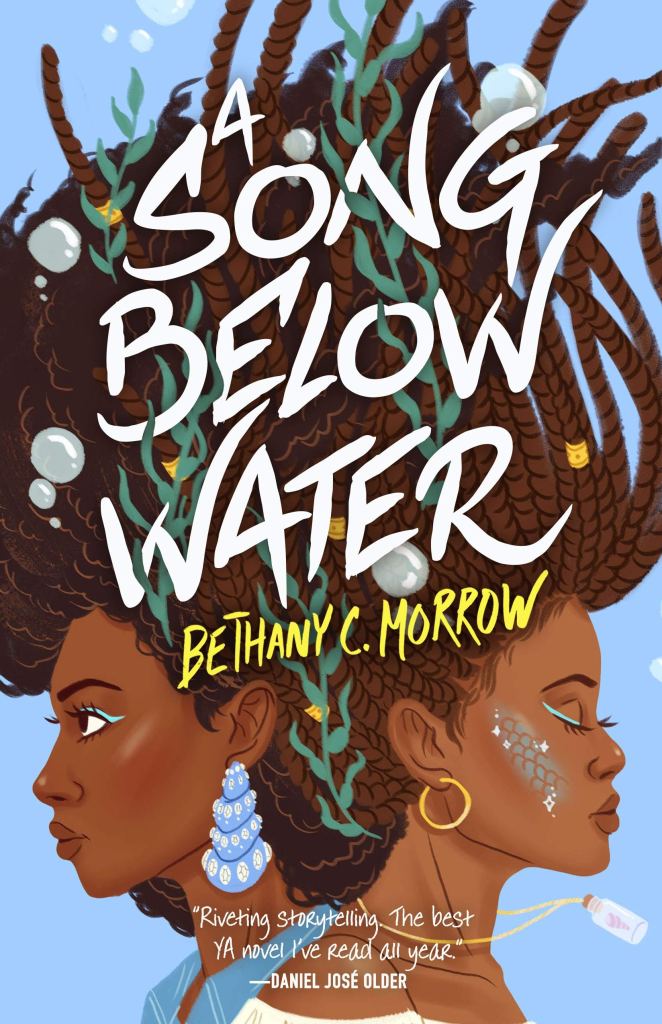

A Song Below Water: A Story of Sirens & Black Girls Coming Into Power

Bethany C. Morrow hopes Black girls will "feel edified, and encouraged, and adored" while reading YA novel A Song Below Water.

It’s all too rare to get contemporary YA fiction that combines a focus on “social issues” with a speculative fiction twist, which was one of the many reasons we were eager to learn more about Bethany C. Morrow’s A Song Below Water. The YA novel is a story of “black mermaids, friendship, and self-discovery set against the challenges of today’s racism and sexism,” an intriguing combination of contemporary themes and genre sensibilities that is set to hit bookshelves in June.

A Song Below Water follows Black teenagers Tavia and Effie. In addition to having to navigate the pressures of high school in Portland, Oregon, Tavia is a siren who must hide her powers for her own safety and Effie is literally being haunted by demons from her past. When a siren murder trial rocks the nation and Tavia accidentally lets out her voice at a police stop, Portland is less safe than ever for these two sisters.

Den of Geek had the chance to talk to author Bethany C. Morrow about bringing this story to life.

Den of Geek: A Song Below Water features two protagonists, Tavia, a siren, and her play-sister, Effie. They are very different girls with distinct personalities and -isms, and the book shifts point of view from one to the other. What inspired that choice?

Bethany C. Morrow: The sisterhood between Tavia and Effie is one of the most important aspects of the story. The way that sisterhood exhorts both girls in their individual developments is a story, I think, best illustrated through centering and revealing both girls, and not one of them through the eyes of the other. I felt there was space for both Tavia and Effie to speak.

How did you manage alternating between the two?

In terms of story, I think it was pretty straightforward, knowing both their storylines and when and where they would intersect, as well as seeding in hints and the like; in terms of voice, I think hearing them distinctly for myself and then allowing the similarities that arise when two people spend as much time together as Tavia and Effie do was key. I read aloud a lot while I’m writing, and that also helps to keep voices consistent, for me.

Tavia is a siren in a world just like ours—with the same prejudices—where myths are real, and all sirens are Black women. How did you conceive of the character?

In conversation with my sister, I said, “My voice is power,” an assertive, knowing statement and I meant it literally; I was talking about why the world gets so frothingly, viciously, violently enraged at the audacity of Black women daring to have opinions online. We were watching it happen on the timeline in real time, and I was referring to the ridiculous gaslighting that comes with it where much of the abuse heaped on the Black woman in question is around the supposed fact that she’s a nobody and she means nothing, and no one cares what she thinks—despite that everyone is dogpiling her to tell her so.

Tavia and Effie are not related by blood, but are sisters nonetheless. This type of relationship is common in real life, especially in the Black community, but is rarely depicted. Can you talk about their relationship and the inspiration behind it?

My parents are both transplants from somewhere else. My dad’s from Chicago and my mother’s from NYC, but they started a family in California, and despite much of my dad’s family moving west, they landed in SoCal, while we’re from NorCal.

The family I’ve always been surrounded by has been play. My godparents, uncles, aunts, cousins—they’ve largely been family not related by blood. It’s a very normal part of growing up for me. My mother figure for all of my adult life has been someone who I was raised calling Auntie, but over time she became Mom, and there is nothing illegitimate about that bond.

I think the Black community has a unique appreciation for found family precisely because we are descended from enslaved people, whose family bonds were intentionally severed again and again. In the book, not only do Tavia and Effie regard each other as sisters, but so does everyone else. You’ll never find anyone undermining that bond, because it’s not up to anyone but the people involved and invested in it, who choose it for themselves.

ASBW is set in present-day, and contains many real-world parallels, especially with regards to the treatment of Black victims of violence, and the respectability politics that put the onus on victims to not be harmed. Why was it important for you to tell this story?

I feel like this question answers itself.

The story is set in PDX (Portland), which feels like a character in itself. What drew you to that setting?

I’ve been spending quite a bit of time in PDX for the past decade because my sister moved there, and has raised her family there. My experience with the fun, quirky, but also seemingly smugly satisfied city, particularly one that often seems to applaud itself for a progressiveness that isn’t necessarily experienced by the non-white marginalized, is why I based the story there.

It’s important to cut through this ridiculous and insidious narrative that there is some place in the United States—a country that has never made amends for slavery, and has only ever offered reparations to former slave owners—where Black people don’t experience the racism built into its institutions. The west coast is not exempt, and Black people who are born and raised there are not “lucky” to be subject to its, perhaps, more polite but no less dehumanizing brand of prejudice.

ASBW includes several species of magical creatures with existing mythos, some well-known like sirens and sprites, and some lesser-known (by western standards), like Eloko. How much research did you do into existing mythology?

I only researched Eloko, because everything else is well-known due to constant exposure.

How much did you adhere to the “common” lore?

I didn’t adhere, but I wasn’t attempting to adhere to it. I wanted to know the origin of the Biloko, of course, because it was important to me to make space for non-Western mythos, but it’s also important to me that non-African descended folks don’t expect my fiction to be educational texts simply because they’re unfamiliar with something. The Eloko in my book are intentionally far removed from the original mythos, and for me it’s a representation of the telephone effect that occurs for many in diaspora cultures.

What do you hope readers take away from ASBW?

In that regard, I think I’m only really concerned with how Black girls specifically feel when they read ASBW, and I hope they feel edified, and encouraged, and adored. I hope they think it has the appropriate weight of the real world aspects, and also a lightness that comes with the joy and friendship and power I hope to have given Effie and Tavia.

Complete this statement, about the book, “come for the ______” stay for the “________.”

“Come for the cover (I mean, look at it), stay for the Black girls coming into their power.”

Anything else you want people to know about the book or yourself?

Keep an eye out next year! I’ll have two releases, one of which will be a Little Women “reclaiming,” and the other will be another story set in the world of ASBW! You can follow me on Twitter and Instagram at @BCMorrow to stay updated!

A Song Below Water is set to hit bookshelves on June 2nd. Find out more about how to pre-order the novel here. Find out more about Bethany C. Morrow here.