Groundbreaking Band Fanny Gives Lessons in Rock History

A reunited Fanny talks new directions, old sessions, and happy mentions of David Bowie, Barbra Streisand, Lowell George, Tim Curry, and Ringo Starr.

It is fitting to find Fanny: The Right to Rock broadcast on PBS. The channel thrives on educational material, and director Bobbi Jo Hart’s documentary teaches many lessons. The film chronicles the career, and captures the reunion of Fanny, a group of musicians who changed the dynamics of rock in the 1970s. The lineup was unique, labels and management executives dubbed them the “female Beatles.” They made history as the first all-women rock band to release an LP with a major record label.

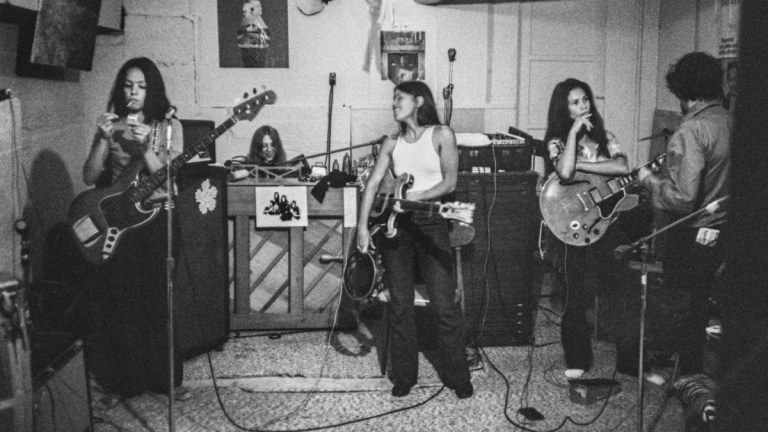

Originally called The Svelts and rebranded as Wild Honey, Fanny was formed in the mid-1960s in Sacramento, Calif., by three Filipina American musicians: sisters June and Jean Millington, on guitar and bass, and drummer Brie Darling. All three sang. When Darling had her daughter, Brandi, in 1968, Fanny added drummer Alice de Buhr, and roving keyboardist Nickey Barclay.

As was the fashion of the time, they lived in a band house. Called Fanny Hill, the documentary makes it seem like the stuff rock dreams are made of. Mick Jagger, Joe Cocker, Bonnie Raitt, or members of The Band, still backing Bob Dylan, might pop by to jam in the house studio. In what amounts to a musical tragedy, the band dropped Darling on the orders of executives at the Warner/Reprise label which signed them. She rejoined in 1974 for the Rock and Roll Survivor album, replacing De Buhr who left the band as well as June, who was replaced by guitarist Patti Quatro, the sister of Suzi Quatro.

Fanny made history, and historic connections. Groups like the Kinks, Chicago, Deep Purple and Jethro Tull requested them as opening acts. But not for any all-girl-group gimmick, Fanny were proficient and professional musicians, forever learning and expanding their chops. Producer Richard Perry, responsible for their first three albums (Fanny Hill, from 1972, was engineered by the Beatles’ engineer Geoff Emerick), put them to work backing other artists, including Barbra Streisand.

Fanny’s fans included David Bowie, who recruited members for the song “Fame,” and inspired their songwriting. Bowie musicians like guitarist Earl Slick and bassist Gail Ann Dorsey appear in the documentary to attest the band’s impact. As does Todd Rundgren, who produced Fanny’s 1973 album Mothers Pride, and Lovin’ Spoonful’s John Sebastian, an early enthusiast. Def Leppard’s Joe Elliott, Kathy Valentine of The Go-Go’s, The Runaways’ Cherie Currie, and The B-52s’ Kate Pierson speak on what they learned from the band.

Fanny: The Right to Rock belongs on PBS because it centers on continuing education, highlighting June’s work co-founding the Institute for the Musical Arts, which runs a Rock ’n’ Roll Girls Camp. The Millington sisters and Darling completed the album Fanny Walked the Earth during the making of the film, and spoke with Den of Geek, along with director Bobbi Jo Hart, on what they are creating now.

Den of Geek: In the documentary, it says no one knew anything else to ask besides you being the first all-female band. Did you see the mere fact that you were working as feminism in action?

June Millington: We didn’t see that in the beginning it all.

Jean Millington: We didn’t look at it as feminism at work. We just knew we were doing what we wanted to do. We were women, and were forwarding [the conversation] about feminism, but that was not our primary concern. It was just to be as good as we could be as a band: to write well, to sing well, to be in the studio, and perform well. That was really the focus. It wasn’t about the feminism aspect of it.

June Millington: When I started to play with [singer-songwriter/pioneering lesbian activist] Cris Williamson in 1975, who is basically the face of women’s music, that’s when I really understood what Jean was alluding to. We just figured we were feminists. That’s the only way we could answer the question, because we would get asked in ‘72 and ‘73: Are you feminist? We just said, well, we think we are.

But once I started to play with Cris, which, by the way, was on the heels of playing with Jean and Brie in The LA All-Stars, it all crossed for me, and I realized: Oh, not only am I a feminist, but I’m part of the feminist movement. I just was swept by the force of the women’s movement. Wow, listen to that. What about you, Brie?

Brie Darling: I was what Jean was saying. I was anywhere from 14 to 18 before I was aware of the political movement of feminism. I was just a woman doing what I loved in spite of any kind of obstacles. In a way, I guess that’s just doing the feminist thing. I support it, of course.

June Millington: We were feminism DIY. I gotta tell you.

Brie Darling: That’s right. That’s right.

You developed recognizable guitar fuzz tones. How do you control feedback?

June Millington: It was police scanners that came in, especially at soundcheck and then during the show. I learned a lot with Lowell George and Skunk Baxter, they taught me the power of how to tune into your guitar and your amp. I learned how to create those sounds with my amp. Oftentimes, I would change the controls in between songs to get what it was I wanted on that particular song.

If I was doing “Badge” for example, I had a Lesley wired onstage, and when that motif came in, I call those guitar motifs [sings the instantly recognizable line]. I hit the switch, and that came in. Plus, I gave it an extra oomph. Sometimes, I had two amps that I would chain together, which is actually what I’m playing tonight, to give me that extra sound. I knew back then, and I know how to manage amplifiers, and really, that’s the key.

I don’t use boxes anymore. Although I think I’ve used every box, up until five years ago, that ever existed. But that got really tiring when I realized I could just do it myself, just fooling around. But that part about fooling around, especially hanging with Lowell and Skunk, they really knew their stuff. They were making up the sounds that are now considered classic rock. That’s who I got my sounds from. I learned how to do it, which is what got me in such big trouble with Richard [Perry, rock producer], because he didn’t want that big a sound. Yet, that was what I was going for. And I thought it was incredible, so that was tough.

The doc makes working with Richard Perry look like a lot of fun. You played a lot of guest sessions. Which were some of your favorites? And I wanted to specifically ask about Barbra Streisand and Ringo.

Jean Millington: Barbra Streisand was amazing. She was just natural, and easy to get along with. The thing that most amazed me about her: When she sang a song, she sang them three different times, each time was different. I couldn’t believe she had that much knowledge and savvy about music. It was just amazing that you could sing the same song three different ways.

June Millington: Yeah, and also, we met her at the Whisky. That’s where we’re playing tonight, so it’s all coming full circle. She came to see Fanny. The fact that we knew her made it a lot more comfortable. She came in with a whole attitude, she kind of pretended she didn’t know the songs. So, I sang it acapella to her. That was fun.

She made it work in a way that worked for all of us. I’m quite sure she knew that that was her job, because we were just this band who were gonna back her up. But she made us feel like a million dollars. And that was real. That’s what an artist, a true artist, does. She understands the situation. She comes in, she takes control, she seizes it, and was completely successful.

As far as other sessions, I played second guitar on [Barbra Streisand’s Laura Nyro-written] hit “Stoney End.” I interviewed Richard a couple of years ago, and we talked about Fanny. We talked a lot about other stuff. I asked him, actually, if he had turned down my guitar because he was afraid that the general audiences at the time couldn’t take that sound level, the extreme crunch that I put in it. He just kind of looked at me, but I could see a “yes” in his eyes. So, I think the answer was yes.

At the end of the interview, I asked, is there anything else about my guitar playing you remember that you can remark on? He said, “Stoney End.” And I’m like, “What about ‘Stoney End?’” And he said, “you put the street into the track.” That is the highest compliment I feel like I could have gotten from Richard, because he knew something about me that he was able to use. I was only second guitar but you can feel it. You can feel it pushing that track along.

The Ringo Starr session, I don’t think we actually met Ringo, did we Jean?

Jean Millington: No, not at that time.

June Millington: But we did meet Ella Fitzgerald. [Richard Perry] produced an album with Ellen in ‘69. And that was unbelievable for us to meet her.

Brie Darling: I did a record with Ringo, one of his solo records. I’m honored to have worked with a Beatle. That was a great time, Vini Poncia. The Rock and Roll Survivors record, Vini Poncia produced it. He was from the Richard Perry organization, and then he did us. He brought me in to do a lot of sessions, and Ringo’s was one of them. That was an honor.

Ringo loves other drummers.

Listen, he’s one of the most influential drummers around. So that was, of course, an honor for me. I sang on his record Rotogravure, so I didn’t get to play drums, and I don’t know if he knew I was a drummer or not. But then we hung out a bit too. I met up with Vini and Ringo and his wife at the time in Amsterdam, and now. He’s a good guy, and I’m so happy for his success now.

The documentary shows David Bowie was a huge fan, and Earl Slick has a great line about how the first artists to come along are the ones who get fucked. But you also played on sessions.

Jean Millington: No, I sang, I didn’t play, that’s different. He was just really wonderful because I was not there to sing, but I was there. He says, “Well, come on down.” It was one of those things: “Oh yeah, okay, great.” I sang on the record. I got paid for the record like 25 years later.

June Millington: He’s talking about “Fame” by the way.

Brie Darling: I was a bonehead. I was in the room when Jean called me up and said “get down here, we’re gonna sing on a track,” and I said, “I’m too high.”

While watching the documentary, I was hoping they’d reveal you were “The Jean Genie.”

Jean Millington: Well, it would have been a compliment, but “The Jean Genie” was kind of about a weird girl, so I’m glad.

Isn’t “Butter Boy” about Bowie?

Jean Millington: Yeah, well, loosely. He gave me the confidence to write the song in the way I did, tongue-in-cheek. You know, “He was hard as rock, I was ready to roll.” He gave me the confidence to go in and make a tongue-in-cheek song. I didn’t write it with him or anything like that. But again, it was about my relationship with David, what was really so nice and loose and supportive.

I’ve wanted to ask this since I was 15. Why do you thank Tim Curry on the back cover of your last album, Rock and Roll Survivors?

Brie Darling: There were a bunch of people that inspired things at the time. And Roy Silver, our manager, took us – Jean and me and probably June – to see the opening of The Rocky Horror Show.

Jean Millington: At the Roxy Theater.

Brie Darling: They took us there to see the opening show, which is very, very different from the film, and in my mind, kind of a lot cooler. Tim Curry walked out from behind us on a bridge that they built for the set, and he was just larger than life and so enigmatic. It was a huge influence. I think that’s probably why, wouldn’t you Jean?

Jean Millington: He was friends with Roy, and we knew him a little bit. I think it was more like that. Well, besides influencing [us] with his sense of confidence, and the way it radiated his personality.

Brie Darling: Yes. I would say he was an influence. Definitely. He was so larger than life.

The documentary looks unflinchingly at Brie’s firing, but Nickey Barclay’s story fades. What did Nickey bring to the group dynamic?

Jean Millington: Well, Nickey is an incredible songwriter. The songs she came up with, especially for the heavy rock and roll like “Blind Alley,” are incomparable. She knew how to put those kinds of songs together. She contributed a real nice edge to the band because she bought the rock and roll into the band. She really did.

I’ve always loved the song “Conversation with a Cop.”

June Millington: In part I would say that it showed a little bit of her paranoia, I’m just out here walking my dog, why are you bothering me? In fact, she was paranoid, so the personal experience worked in the song. You feel a little bit of paranoia, and you feel like you’re on her side. I’m just out here walking my dog. Why are you bothering me? Right? But within the band that paranoia was a lot more expressive, and that was difficult.

Brie Darling: I thought that Nickey was and still is an amazing songwriter, an amazing musician, and an amazing singer with a very odd voice. She was an integral part of the band’s more rock side.

Fanny was promoted as “the female Beatles,” and this is kind of an anti-Let It Be, you document the reunion of the band not the breakup.

Brie Darling: I like that.

How did you capture the dual journeys?

Bobbi Jo Hart: I discovered Fanny about seven years ago. I’d never heard of them, myself, and I knew I wanted to make a film that celebrated them, and brought their groundbreaking contributions to the knowledge and appreciation of the greater public in the U.S. and around the world.

But I also knew that I didn’t want to do a film that was fully based on archives. [I wanted to show] that, as I got to be in touch with the bandmates, their musical savvy was still so vibrant, and their interest. So, when I heard about the band reuniting, when June told me they were getting back together, with a rock record deal, I thought it was the perfect serendipitous moment. Because I could follow the forward momentum arc of them getting together creating this album, releasing this album, and intercut that with the backstory of all these amazing archives. Using jump-off points to go back, and then come back to the present.

Thank goodness, I had an amazing editor, Catherine Legault. We spend a lot of time and energy trying to find those pieces, to go back and forth in a way that felt smooth, or as smooth as possible. That was a challenging, but really amazing journey: To be able to have the backstory, but also celebrating them as they’re kicking ass today.

I wanted to close on your connection with Angela Davis, after her introduction to “Brown Like Me?”

June Millington: Angela Davis has been a friend of mine since the mid-’80s. She helped us, my partner Ann Hackler and me, found The Institute of Musical Arts. I was talking to her in San Francisco. I was telling her, and I didn’t really speak about this to too many people because they might think I was crazy but I knew Angela would understand. I said, “Well, I started hearing a voice about 10 years ago [saying], in the women’s music scene, who’s going to take care of all the women coming up after you? I’m hearing more than one voice now. They’re actually coming in my dreams.”

She looked at me and said, “Well, get going.” I’m like “What? Not me!” But she said the only thing that would give me the heart to go on. She said, “well, but they’re talking to you.” That was her connection with us, with everything. Because she found the exact right words to get me to follow the edict I was getting from above, which is “help take care of the younger girls who are coming up after you.”

That’s exactly what we’re doing with the Institute for the Musical Arts, which is a nonprofit organization. But Angela Davis, we are actually kind of a subversive organization, but we don’t say that. She’s part of our founding board. She totally understood what we were doing. She gave us, and she continues to give us a hand. That’s why she did the intro to “Brown Like Me.” She totally understands the importance of everything that’s in that song.

Fanny: The Right to Rock premieres on PBS on May 22 at 10 p.m, and will stream on PBS.org and the PBS app.