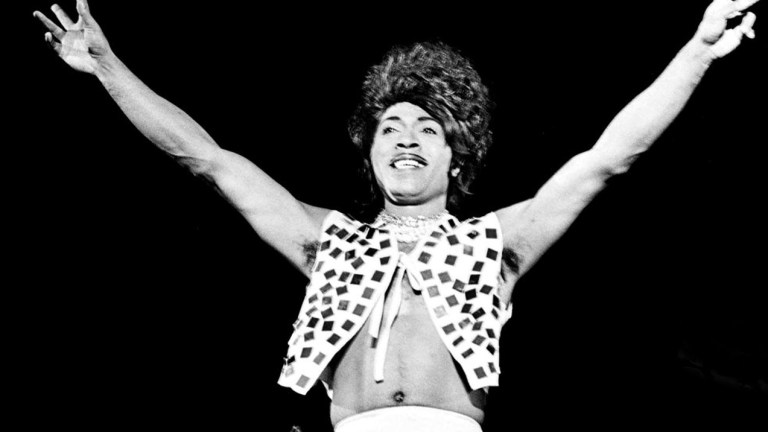

Little Richard Doc Director on How the Architect Connects to Tom Jones, Led Zeppelin & Hairspray

Exclusive: Director Lisa Cortés explains why the title Little Richard: I Am Everything is not an overstatement.

Little Richard always told it the way it was, and coined the phrase “Shut up!” to emphasize his impact. When he inducted Otis Redding into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, in between note-perfect impressions of his fellow Macon, Ga.-born soul singing friend, Little Richard paused to ask how come no one was recording him. He still looked good, he obviously sounded great, and the “Architect of Rock and Roll” wasn’t even doing his own songs, but those of a singer he loved, respected, and inspired in equal measure. Little Richard was the guy who sang “you keep a-knocking but you can’t come in.” Why weren’t record companies breaking down his doors?

Director Lisa Cortés’ Little Richard: I Am Everything demands answers and explores deeper questions. The documentary shows Little Richard Wayne Penniman’s journey to be a complex one. Entertaining, yes, but engaging in ways the teenyboppers who danced to the singles may have never imagined. Cortés presents a conflicted revolutionary rocking his pendulum between the sensual indulgences of secular music, and the self-torment of a deeply religious believer truthfully afraid for his soul. As the song says, the girl can’t help it: Cortés is an Academy Award-nominated and Emmy-winning producer/director on the inside of the music industry since she began her career at the Def Jam label.

Cortés’ 2020 directorial debut, The Remix: Hip Hop X Fashion, measured the inseam of street fashion and found it extended globally. Her production of the Emmy-winning HBO documentary The Apollo (2019) kept it proudly local. All In: The Fight For Democracy, co-directed by Cortés and Liz Garbus, is universal. Little Richard: I Am Everything unearths the transgressive roots of the rock ‘n’ roll originator, but the director never lets the audience forget why the singer appealed to everyone. Segregation crumbled on the dance floor before marches found their beat.

Speaking with Den of Geek, Cortés called the tune. The music industry veteran and cinematic contender sees Little Richard’s most exciting legacy as an “invocation to start a big party,” and invites the world to dance.

Den of Geek: Were you a Little Richard fan going into the project or did something evolve over the works?

Lisa Cortés: I was a fan going in, but I fell in love with him making the film.

Besides putting boogie-woogie rhythm to barrelhouse blues, Penniman was a great lyricist. What does “a wop bop a loo bop” say to you?

It sounds like an invocation to start a big party.

Your doc features artists who also deserve their own documentaries. How was Billy Wright and Esquerita’s influences on Richard a two-way street?

Well, I think what’s interesting is Billy Wright and Esquerita predate Richard, in terms of when they’re on the scene. They bring not only musicality, in the case of teaching Richard how to play piano in a more unique and expressive way. They’re also bringing queerness. They’re out. They’re outlandish. So, it is performance, it’s lifestyle, and it’s music that they are able to bring to Richard, which he then builds upon in his own unique way.

I am a weird music searcher, I love finding things like Louis Armstrong pot songs or the Clovers doing raunchy B-sides. When you run into a golden nugget like “Shave ‘em Dry,” from 1937 no less, what goes through your mind, and in what order?

Well, I didn’t know about Lucille Brogan. But I knew the tradition that she was from. I think it’s very important, in this film, to show who are the foremothers and fathers who exist in a space before Richard, that he, in his own way, is drawing from.

I mean, I love the double entendre in the lyrics. I love the unapologetic delivery and boldness. And, this is a counter-narrative to what we expect from women to be presenting, particularly in this period. We’re not hearing these voices. This is the same time as The Great Migration. And to be so sassy, to say the least, I’ll let you quote the lyrics, and forward. I think it’s a part of our great American music history, that there’s still much more stories to be told about these pioneers.

You made a great case, quite subliminally I might add, for showing how Little Richard influenced artists outside of rock ‘n’ roll. As a director, what do you see as his influence on John Waters, besides the mustache?

Well, one of the reasons I was interested in speaking to John Waters was John Waters actually met Little Richard. He wrote this famous article for Playboy. And then Little Richard was like, “I don’t want you to print it.” And it’s like this really funny, crazy story.

But I was very interested in Hairspray. To me, what John Waters is doing in Hairspray is an examination of the birth of the American teenager, and in particular, how rock ‘n’ roll affected teenagers, and looking at racism. I kept saying, can we find a way to incorporate Hairspray, or a clip from it, into the film? Due to time constraints, we couldn’t. But I always thought about how, in John Waters’ narrative work, he had explored the same scene, in what happened with rock and roll, to bring together white and Black teens in our country.

You might remember Divine’s appearance as Tracy’s mother. But there’s a greater social commentary, and musicality in that film that people might not decipher.

Your work on The Remix: Hip Hop X Fashion begs me to ask what influence Little Richard had on fashion?

Oh, we see it everywhere. I mean, Harry Styles’ mirror suit, who did it first? Little Richard. Just gender bending, in terms of how performers are mixing waters that are supposedly masculine and feminine fashion. There’s so much that Richard did with affecting gender fluidity in terms of your forward-presenting persona, that he’s not really recognized. He is thought of as “wop bop a loo bop,” but there’s so much more to him. And, as a transgressive figure, the effect that his very being has on popular culture.

Some of the greatest artists have been sidelined because of false narrative, Billie Holliday is as known for drug use as her voice, which is a gross misrepresentation. Did you avoid or reframe certain things because of how history picks on the foibles of Black artists over their art?

Well, the framing principle of this film is for Richard to tell his story, and to narrate it. And not only narrate the great accomplishments, but also to talk about things that are somewhat challenging for us to accept, like his renunciation of his queerness. I wanted Richard to have agency. When I started the film, I did a very deep dive into archival, to make certain that we could find Richard’s voice through the years. He is our North Star. He is our guide. That process, to me, gives transparency to the different Richards throughout his life. The rock ‘n’ roll Richard, or the super-religious Richard, they all speak, and tell that portion of his story.

Did you try to speak with any of Richard’s male lovers? And what kind of perspective do you think they might have added?

I wish I could have found them. I certainly asked. I spent time at the hotel, the “Riot” Hyatt in Los Angeles, where he lived, and talked to some people who were working there when he was in residency for many years, but I couldn’t get any leads.

Do you have any intuition on what kind of perspective they would have brought?

Right, I don’t know, because Richard is very telling in the film when he says his greatest love is with God. I think he did have an incredibly powerful relationship with Lee Angel. But ultimately, I think, one of the most ecstatic relationships he had was through his faith.

I imagine some of the artists who spoke with you who are fans of his had a lot to say that didn’t fit into run time. I’m assuming Mick Jagger had an excess of analysis. What do you wish didn’t land on the cutting room floor?

I have to say [the full interview] with Tom Jones, because Tom Jones continued his relationship with Richard. He told the story that, toward the end of Richard’s life, he was in Tennessee, he had a little plane. So, he says, “I’m gonna go see Jerry Lee Lewis. I’m gonna go see Richard.”

He told me a story that actually other people have shared, which is: Richard would pick up the phone and say, “Richard isn’t here.” He was a prankster also, and Tom Jones is like, “I know it’s you Richard,” and he’d go “no, no, no, no, no, he’s not here.” Which I just thought was really funny and playful. And then he finally fessed up to being like, “Yeah, it’s me. But I don’t have my hair done. I don’t have my makeup on.” And Tom Jones is like, “I’m just coming to see you.” I love that. I love that. I could just see that playing itself out, which is really sweet in its own way.

Can you tell me about Little Richard as a TV personality?

Oh, he relished it. He relished having that platform, and that engagement, not only with the hosts, but also with the audience. We have some beautiful footage we couldn’t use. But behind-the-scenes when Richard was on Full House, there’s this great moment, this is stuff that John Stamos shot, and it’s him and John just jamming. This is not a part of the show. He just started playing, and then John just jumped in, and they just had such a great time. He enjoyed those moments, to stay present and still be relevant in some way.

Who else might you turn your lens on?

Oh, there are several music artists that I would love to tell their story, from Stevie Wonder to Sade to Cher.

I heard you are a huge fan of Sister Rosetta Tharpe. Tell me a little bit about what she did for Little Richard and who she is to rock and roll.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe is coming from the gospel tradition. She’s plugging in the guitar. She’s bringing the rock and roll. She lives a larger-than-life experience. I mean, for one of her marriages, she got married in a stadium, and people bought tickets to come see it.

She’s also queer. And she meets a 14-year-old Little Richard at the Macon Auditorium. She hears him sing outside, and invites him to perform with her. And Sister Rosetta was one of Richard’s favorite artists growing up, so you can imagine a kid who’s been kicked out of his house for being queer. He meets her and she says “come perform with me.”

That really opened up a sense of possibility for Richard. I think it says a lot about her generosity, her recognizing the non-normative in Richard. And, she is so deserving of her own story being told, because of the innovation that she brought, the musicality. I love seeing her performances. There’s some famous stuff online when she was in the UK, where she’s testifying not only through her voice, but how she is using the guitar. It is free. It is unbridled. And she gives the voice of gospel to the guitar.

You show Little Richard was obliterated by pop historians. What does the average music fan miss out on from Little Richard that we get from Ray Charles or Chuck Berry, and what makes Richard more dangerous?

Oh, well, he is so dangerous because he was unabashedly loud, innovative, uncompromising in his presentation. When he arrives on the scene in 1955, there is nobody like him. And it’s not just sound, it is appearance. It is, in his own way, challenging the norms. It is asserting the importance of Black cultural product. For Richard, what I am always excited about is looking at where his legacy is in places that we don’t expect.

One of my favorite songs I could not use in the film, for timing purposes, is “Keep a Knocking But You Can’t Come In.” It has the most brilliant drum intro. That great drum intro then becomes the beginning of another classic rock and roll song by Led Zeppelin called “Rock and Roll.”

So, you go, “Wow! This family tree,” the things that he begat: whether it is Prince, whether it is literally his music being incorporated into this great track by Led Zeppelin. His influence is everywhere. It is profound. And it is part of a ripple effect that has helped to change culture.

Little Richard: I Am Everything can be seen in theaters and on demand April 21.