Fanny: The Right to Rock Spotlights a Boundary Breaking Band

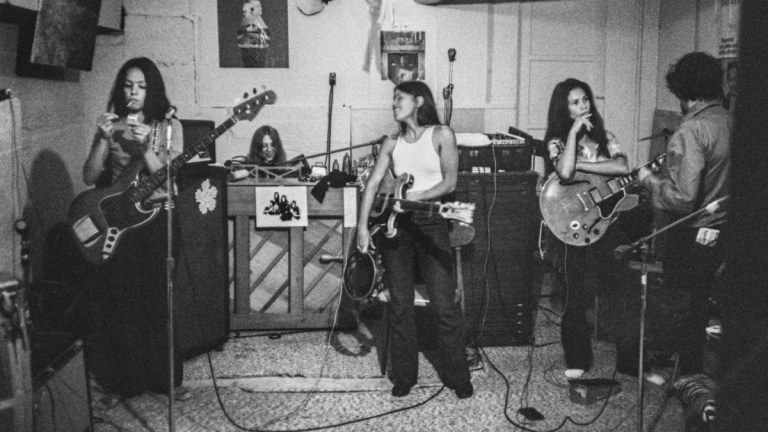

Fanny: The Right to Rock is an intimate and loving look at a band which deserves more focus.

From the moment their first shows were advertised, Fanny was promoted as an all-girl band, but the label wears thin in director Bobbie Jo Hart’s Fanny: The Right to Rock. Each member says it themselves in the feature documentary, and tried telling record companies there were far more interesting things to say about them beyond the mystery of their gender. They broke through, but only barely, because sexism in rock and roll was so deeply ingrained psychologically, not even the promotion departments could think of anything else to say.

This is probably why Alice de Buhr remarks, at one point in the film, that every kick on her bass drum was a kick in a crotch. Fanny was committed to the music. The group’s members included bassist Jean Millington, guitarists June Millington and Patti Quatro, keyboardist Nickey Barclay, and drummers de Buhr and Brie Darling. Their sound was both of and ahead of its time.

Fanny: The Right to Rock speeds through the band’s development, presenting an easy guide to the main points. The Millington sisters were born in the Philippines to a Filipino mother and an American naval officer father. They’d been playing since they could get their fingers around ukuleles. They moved to Sacramento, California, in 1961, and three years later formed the Svelts, along with Barclay and Darling. They changed their name to Wild Honey in 1968, and to Fanny with their first record deal.

The name has double meanings and, early in the film but later in the game, Brie gives out “pussy-power secrets,” like how mini-pads make the best drum dampers. The nostalgia is fun, especially tales about the band house, called Fanny Hill. Joe Cocker stopped in for breakfast, Mick Jagger brought hash and Bobby Keys, and clothing was optional. The talk was all about music, but the vibe churned hot. Fanny’s biggest hit, “Butter Boy,” which opens with the line “He was hard as a rock but I was ready to roll,” was Jean’s song to David Bowie, who she dated for a year in the early 70s, and credits with helping her stretch her songwriting skills. She also sang background on “Fame.”

The documentary finalizes one of Bowie’s visions: To make people aware of this band. “They were one of the finest fucking rock bands of their time,” Bowie told Rolling Stone in 1999, which the film takes as a mission statement. “They were extraordinary: They wrote everything, they played like motherfuckers, they were just colossal and wonderful, and nobody’s ever mentioned them. They’re as important as anybody else who’s ever been, ever; it just wasn’t their time.”

Fanny: The Right to Rock is a loving look, but not a deep dive. The primary function is a solid one. Fanny members reunited with a new name and an eponymous debut album, Fanny Walks the Earth, the production of which is documented very well. They are dinosaurs who still get around, and should be remembered as the pioneers they were. This is noted in the interviews which include Todd Rundgren, who produced their fourth album, Mother’s Pride; The Lovin’ Spoonful’s John Sebastian; Runaways singer Cherie Currie; Bowie’s touring bassist Gail Ann Dorsey, and his guitarist Earl Slick, who was married to Jean Millington.

“It’s always the one that starts it that gets fucked,” Slick says in the documentary. Fanny was never as well-known as The Runaways, The Bangles, or The Go-Go’s, because they didn’t have a big identifying hit. The documentary makes two points on this. The music industry didn’t support them beyond a single identity, and each member of the band had to hide a part of theirs.

Fanny was a (gasp!) mixed race band, the Millington sisters and Darling were Filipina-Americans who faced open discrimination and casually cruel prejudice growing up, and a far more insidious bias as adults in the entertainment industry. They weren’t asked about their backgrounds in the many TV appearances they made, that would have been too deep. Fanny: The Right to Rock further highlights how fame also squashed any chance for the queer members of the band to speak out as lesbians or in solidarity with the gay movement of the time. When the documentary focuses on de Buhr speaking about being institutionalized for coming out at age 17, it highlights how much they had to say.

“If somebody had asked me, I would have talked about it, but nobody did,” June notes in a more recent interview in the film. “We couldn’t talk about racism or sexism.” Subtly racist reactions occasionally happened when an audience first saw Fanny come out on stage, but as soon as they plugged in, everything was forgotten. “People didn’t fight about race while dancing,” she says.

Learning some of the bandmembers had to pretend to have boyfriends makes it clear the music industry was no less homophobic than the film industry, which paired up gay actors with presentable counterparts for public appearances during its Golden Age. The documentary also subliminally shows, mainly through one of many fond and mischievous recollections from Bonnie Raitt, how accepted it was among the musicians who got close to the band. The studios turned the knobs way down on it.

When Fanny was picked up by Warner Bros.’ Reprise Records, major labels had only signed a few all-female rock groups, including Goldie and the Gingerbreads, and the Feminine Complex. Some bands did make it to the smaller labels, like the Pleasure Seekers, which included future Fanny guitarist Patti Quatro, and her sister Suzi Quatro, who would take the next step in rock consciousness after Fanny cracked it open. The industry and the audience of the time had no problems with women as rock or soul stars. They just didn’t want to see them play instruments.

There were notable exceptions. Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Peggy Jones rocked any house, but their fingers were made for breaking ground. Joni Mitchell, Melanie, Janis Ian, and Joan Baez displayed exceptional fingerpicking skills, but were folk or protest singers. Aretha Franklin and Laura Nyro were tremendous at the piano, but known as singers and songwriters. “Wrecking Crew” session player Carol Kaye did double duty on electric guitar or bass on some of the biggest hits known to man. The documentary could have noted Barclay was also a session player, as part of the Musicians Contact Service. In fact, the whole band played sessions.

Fanny backed Barbra Streisand for her genre-breaking Stoney End and Barbra Joan Streisand albums. The pairing was the first time Streisand recorded live in the studio with a rock ensemble. Richard Perry, who produced Fanny’s first few albums, used them as session players. Fanny also arranged two songs: “Space Captain,” which featured Billy Preston on keyboard, and Carole King’s “Where You Lead.” These and the band’s cover material have been excluded because only Fanny original compositions are featured in the documentary. This is a shame because they further exemplify the diversity of these musicians.

Joe Elliott of Def Leppard occasionally runs the risk of stealing Fanny: The Right to Rock with his enthusiastic appreciation. He identified with the band personally from the first flex-disc he heard. They did the same things he did, lugging equipment from one gig to another, and with the same commitment. The only difference was men in the audience yelled ruder things at Fanny. He shines most when he starts breaking down musical parts. The documentary is loaded with vintage TV performance clips, but Elliot, more than any of the other musicians interviewed, makes the viewer want to go back to the vinyl.

Fanny released five studio albums between 1970 and 1975. Perry produced the earlier albums, and the documentary sounds the age-old guitarist complaint. He turned down the amp. June cranks it back up for Geoff Emerick, former engineer to The Beatles, who just has to mic it to get the perfect sound for the 1973 album Fanny Hill. June, who could bring out expressive tonic overtones in controlled feedback and a tasteful slide player, also wrote the softer melodic songs like “Long Road Home,” and “You’ve got a Home.”

Jean, who wrote “What’s Wrong with me?” and “Wonderful Feeling,” is a steady bassist who excels in harmonic counterpoint. She only occasionally augments into dangerous interplay, saving it for sonic climaxes. This is evident on “You’re the One,” written by the two Millingtons for the album Charity Ball. Sung by all members, in their signature unison-to-harmony explosions, the song gets away with the line “make you come,” and is grounded in the throbbing rhythmic foundation. It allows June to explore artful distortion on her solo, and Barclay to counter with a beautifully non-linear jazz-tinged piano lead.

Barclay is absent from any contemporary interview footage in the film. We hear in the documentary that she refuses to have anything to do with the band, but are never given any reasons. Barclay wrote most of Fanny’s harder songs. Heavily infused with blues, she also brought understated funk to the mix, such as her song “Place in the Country.” Rock industry executives wanted to promote Fanny as the female Beatles, even forcing the band to pull a Pete Best maneuver in one of the film’s sadder sequences. Barclay’s deceptively introspective, John Lennon-ish “Conversation with a Cop,” from Fanny is a must-hear as counterpoint to the songs in the documentary.

Fanny: The Right to Rock is deeply frustrating on many levels. It uses some of the frustration to push for ground-level change, such as when it focuses on June’s work co-founding the Institute for the Musical Arts, which runs a Rock ’n’ Roll Girls Camp. The film has a much more shocking and sad obstruction in the third act, right after the Millington sisters and Darling complete Fanny Walked the Earth, but just before they are about to embark on the first tour. Even here they ride a hopeful note on the promise of more music. The film is, in many ways, a therapy session. Fans get more of a psychological insight into the band than most rock documentaries.

Fanny: The Right to Rock is a very intimate look at an ever-evolving group of players, which explores racism, sexism, and ageism from unique perspectives. It is also an enjoyable and educational watch, but it doesn’t quite match the fire of the band it is celebrating, even as it teases at the possibilities in Fanny’s story. The band’s overall stylistic range is under-represented, so follow this up with a dive into deep album cuts. The film is probably not going to spark the fire it sets out to ignite, but it should.

Fanny: The Right to Rock is playing in select theaters.