A Guide to the Comics That Have Inspired James Gunn’s DC Universe

Dive into the DC Comics archives to find the comics that informed James Gunn's DCU.

Even though he and Peter Safran have only been the co-chairs of DC Studios since 2022, James Gunn has already made the shared storytelling universe his own. The three projects released since then—Superman, Creature Commandos, and Peacemaker season 2—have all born his trademark, as do the upcoming movies Supergirl and Clayface and the series Lanterns.

But as much as James Gunn has an idiosyncratic style, and as much as he tends to avoid directly adapting storylines, it’s clear that certain runs and eras of DC stand out as inspirations. Based on Gunn’s comments and the types of stories he likes to tell, here are the DC Comics runs that seem most important to Gunn and his vision of the DCU.

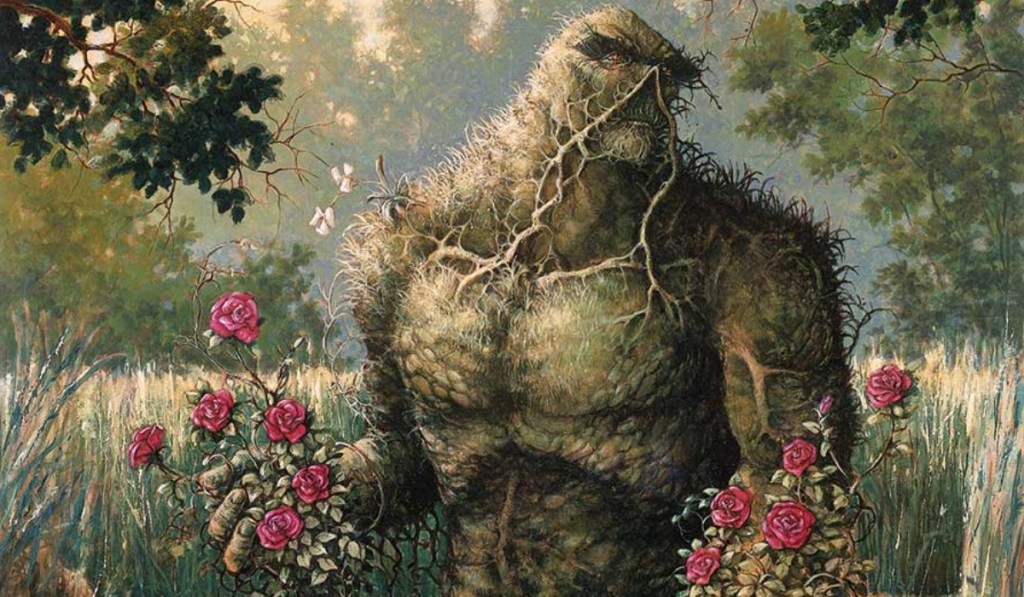

The Saga of the Swamp Thing (1984–1987)

Shortly after taking the top job at DC Studios, Gunn shared on social media some comics that he recommends. That list included The Saga of the Swamp Thing, the groundbreaking horror comic that brought Alan Moore to the attention of the average reader. Just a few weeks ago, Gunn once again shared an image from the series, reminding us that he really likes Swamp Thing, even though there are currently no projects with the character in development.

It’s not hard to see the appeal of Swamp Thing for Gunn. The story of scientist Alec Holland who transforms into a plant monster—or of a plant monster who thinks he’s Alec Holland—Swamp Thing isn’t just a mix of superheroes and horror, it’s also a deeply romantic story. We don’t often see much of Alan Moore’s high-concept storytelling in Gunn’s work, but anyone who loves DC Comics at least has a respect for Moore’s work.

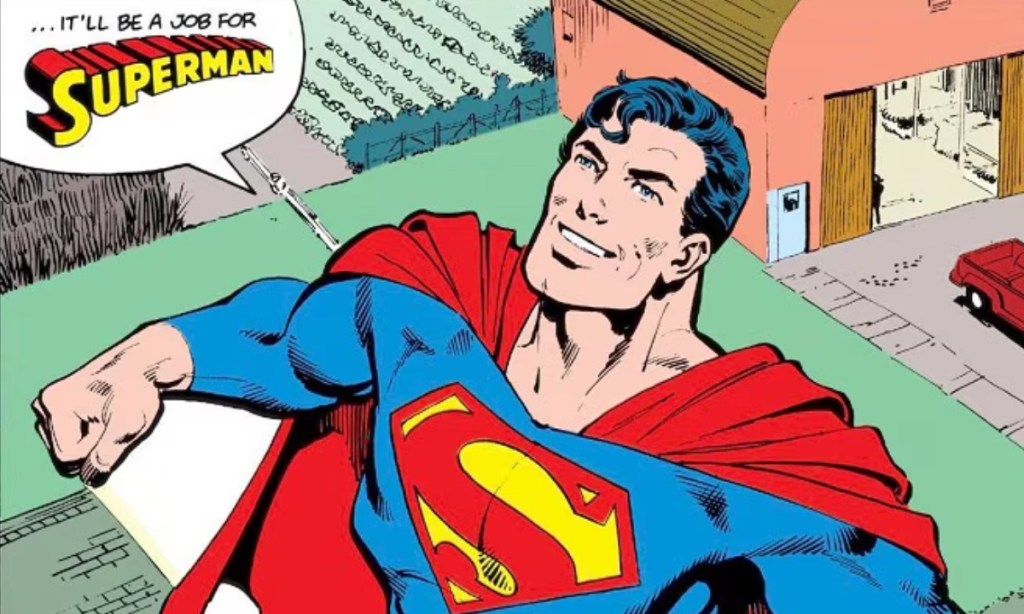

Man of Steel (1986)

Leading up to the release of Superman, Gunn made plenty of references to Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely’s All-Star Superman. And to be sure, elements of that comic do show up, with crazy concepts like the kaiju attack and portraying Lex Luthor as a straightforward, immoral villain. But some of the best parts of the movie came from another, very different Superman comic.

Released around the time of the Crisis on Infinite Earths reboot, the miniseries Man of Steel served to reimagine Superman for the modern age. Writer and artist John Byrne did away with some of the more outlandish parts of Clark Kent’s history, including over-the-top powers like super-ventriloquism or the existence of Superboy, and gave us a more grounded, realistic Superman. All-Star Superman may be the exact opposite of the character from Man of Steel, but when Clark Kent and Lois Lane have their argument about Superman’s role in international relations, that’s more Byrne than it is Morrison.

Suicide Squad (1987–1992)

Really, it all starts with Suicide Squad, and not just because Gunn’s first DC project was The Suicide Squad, released before he even rose to the top of DC Studios. Rather, it seems like the DC Comics of the late 1980s and early 1990s are most important to Gunn and shaped his perceptions of these characters, particularly when done by writer John Ostrander and artist Luke McDonnell.

Launched in 1987, Suicide Squad introduced some of Gunn’s favorite characters, including Rick Flagg, Amanda Waller, and John Economos. It also gave plenty of attention to the sort of goofy Z-listers that Gunn adores, such as Captain Boomerang and Javelin. The highlight of Ostrander’s run was the Janus Directive crossover, which involved other Gunn favorites Checkmate, Peacemaker, and Vigilante.

Justice League International (1987–1989)

Gunn’s favorite version of the Suicide Squad debuted in Legends, the company-wide crossover that followed up on Crisis on Infinite Earths with a story about the public doubting its heroes. The end of that series saw the launch of a new version of the Justice League, the flagship team of the DC Universe.

However, this incarnation, dubbed Justice League International (JLI), was unlike any superteam that came before, or would come again. Created by writers Keith Giffen and J. M. DeMatteis and artist Kevin Maguire, the JLI was like a sitcom version of a superhero team, in which big guns like Batman and the Martian Manhunter rubbed shoulders with scrubs such as Blue Beetle, Booster Gold, and, of course, the bad attitude Green Lantern, Guy Gardner.

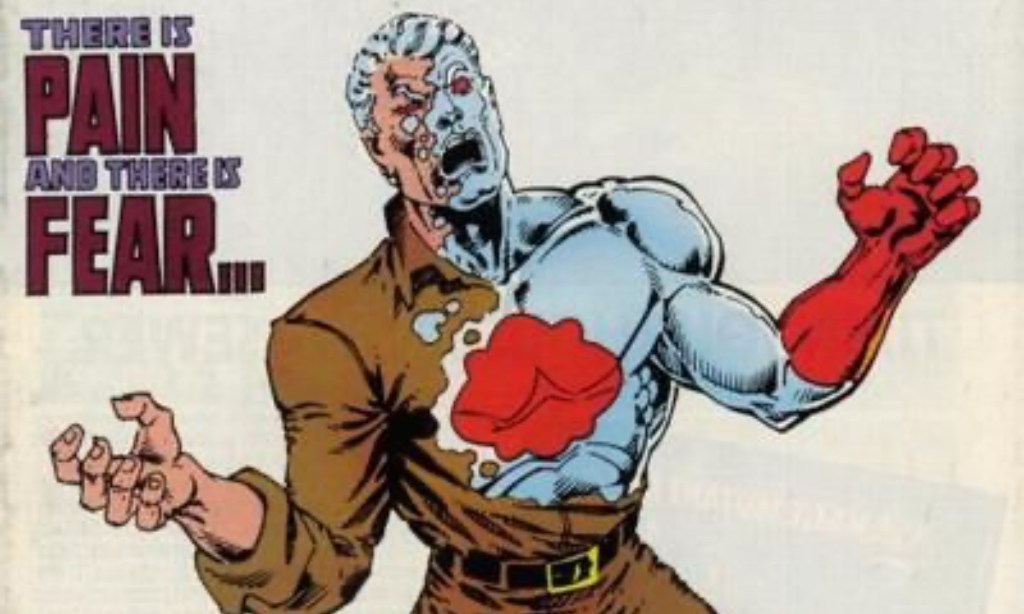

Captain Atom (1987–1991)

Where most comic fans know the characters that DC bought from long-defunct publisher Charlton Comics as little more than the inspiration for Watchmen, Gunn clearly has affection for the heroes as they were integrated into the mainline universe after the Crisis. He’s already put Peacemaker and Judomaster on screen, and if rumors about Creature Commandos season 2 are to be believed, Captain Atom, the guy who inspired Doctor Manhattan, will be coming soon.

Captain Atom is a strange character, but one who fits the Gunn approach. On the surface, Nathaniel Adam is a straightforward military man, a guy willing to do his duty for his country. But when an experiment gives him nuclear powers, he finds himself coming closer to godhood than he had ever wanted or imagined. Famously, DC intended to turn Captain Atom into the Monarch, a villain from the future, and while a clunky, last-minute rewrite spared the hero from that fate, he’s always had a cloud hanging over him. That dark cloud, combined with themes of the government’s involvement with superheroes, makes Captain Atom an ideal Gunn character.

Green Lantern: Emerald Dawn (1989–1990)

The HBO series Lanterns releases later this year, but if you wouldn’t know it from WB’s marketing. In contrast to the full push given to Supergirl, the show about Green Lanterns Hal Jordan and John Stewart has just a still featuring stars Kyle Chandler and Aaron Pierre, a quick clip, and a logo. Moreover, there has been a surprising lack of green in this show about Green Lanterns, as we still haven’t seen the heroes in costume and even the logo is pretty monochrome.

While that might worry those expecting lots of weird aliens in a show about space cops, the dour aesthetic does have a comic book precedent. The 1989 miniseries Green Lantern: Emerald Dawn by writers Christopher Priest, Keith Giffen, and Gerard Jones and artists M.D. Bright and Romeo Tanghal retold the origin of Hal Jordan, imagining him as an guilt-riddled alcoholic who has heroism thrust upon him. The success of that series spawned a sequel and a relaunched regular series, which featured a greying Jordan hanging around the California desert, and looking a lot like Chandler in the few bits we’ve seen from Lanterns.

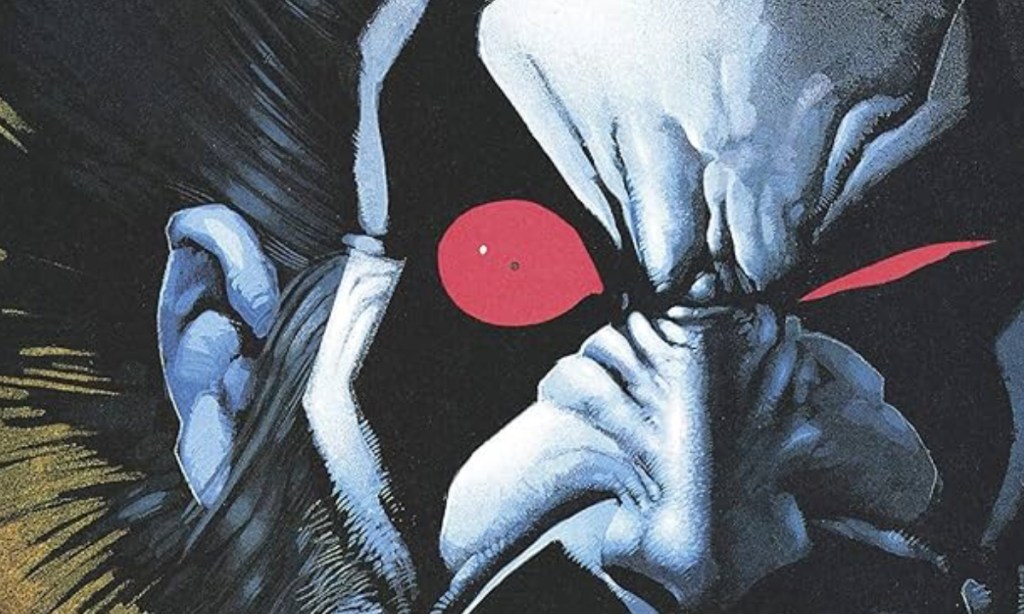

Lobo (1990–1992)

Given Gunn’s origins as a writer with gross-out indie moviemakers Troma Entertainment, it’s almost surprising that we’ve had to wait until Supergirl for the Main Man Lobo to show up. While Keith Giffen may have introduced him as a generic antagonist in 1983’s Omega Men #3, he and his co-creators Alan Grant and Simon Bisley soon turned Lobo into an over-the-top satire of the edgy comics that became all the rage in the 1990s.

Nowhere is that more clear than in the 1990 Lobo miniseries and its 1992 sequel Lobo’s Back, the latter of which proudly showed Lobo’s back and his bare backside on its first issue cover. The series establishes Lobo’s ridiculous backstory, revealing that he killed everyone on his planet because an elementary teacher gave him a bad grade but also showing how much he loves space dolphins. Lobo is exactly the type of extreme humor and surprising sweetness that Gunn loves, so there’s no doubt that he read these comics.

Top 10 (1999–2001)

Even more than Swamp Thing, the most surprising comic run mentioned in Gunn’s early batch of recommended DC works is Top 10, by Alan Moore and artists Gene Ha and Zander Cannon. Unsurprisingly, given Moore’s involvement, Top 10 is a superhero deconstruction. However, unlike his most famous works, there’s an optimism and playfulness to Moore’s approach, which reveals a love for the genre.

Top 10 takes place in a megacity where everyone—men, women, kids, pets, and everything in between—has superpowers and wears crazy costumes. The series focuses on the police officers who patrol this city, marrying the banal realism of an Ed McBain novel to capes and cowls. As an imprint done for WildStorm Comics before DC acquired the latter (much to Moore’s chagrin), Top 10 exists outside of mainline continuity, so it’s hard to see how exactly Gunn would use the material for the DCU.

The Authority (1999–2002)

Like Top 10, The Authority was a WildStorm book disconnected from the DC Universe, and it’s easy to see why. Created by Warren Ellis and Bryan Hitch, The Authority is a realpolitik take on the Justice League. Where Superman and Batman try to inspire people to be better and respond to villain threats, Midnighter, Apollo, and their other ultra-powerful heroes take it upon themselves to build a better world.

The combination of big screen visuals and amorality made The Authority electric in its original run, and it only grew more relevant in the years of America’s War on Terror. Yet, the series’ tendency to be mean-spirited, especially when writer Mark Millar took over with artist Frank Quitely, has not aged well. That said, The Authority has found new life after being integrated into mainline DC, and Gunn has cited an adaptation as one of the first things he wants to tackle in his DCU.

DC: The New Frontier (2004)

As with many of the books on this list, DC: The New Frontier will likely never be directly adapted, but it does inform Gunn’s approach to the characters. Written and drawn by Darwyn Cooke, New Frontier retells the dawn of the Silver Age as a single, coherent story. While all of the Silver Age heroes make appearances, it focuses mostly on Green Lantern Hal Jordan, Martian Manhunter, and Superman.

Through those characters, Cooke approaches real-world problems like PTSD from the Korean War, McCarthyism, and expanding American interventions in foreign countries. But Cooke’s retrofuturist stylings retain an optimistic gleam, especially as the heroes come together to form the Justice League. New Frontier’s combination of sadness and hope perfectly captures James Gunn’s view on superheroes.

Infinite Crisis (2005–2006)

Infinite Crisis doesn’t seem like the type of series that would have a life beyond comic books. Released for the 20th anniversary of Crisis on Infinite Earths, Infinite Crisis was both an homage and scapegoating of that famous multiverse story. Writer Geoff Johns, working with a team of artists, brought back several concepts from the original, including the big bad the Anti-Monitor, as well as some of the survivors from the multiverse collapse, including the Golden Age Superman and Superboy-Prime.

However, Johns also suggested that the darkness and violence of the modern DC Comics stemmed from a loss of innocence that followed the Crisis, instead of, you know, the dark and violent comics that Johns wrote. Still, between big weird concepts like Captain Marvel villain Mister Mind becoming a giant moth that restarts the multiverse and the introduction of Sanctuary, the planet that will be the focus of the Superman sequel Man of Tomorrow, it seems that Infinite Crisis was a favorite of Gunn’s.

Checkmate (2006–2009)

In the final episode of Peacemaker‘s second season, Chris Smith and the 11th Street Kids rebrand themselves as a private superhero agency called Checkmate. Even though this version of Checkmate has little to do with the global intelligence group in DC Comics, Gunn has said that he’s drawn inspiration from that organization for other parts of the DCU.

In particular, Gunn points to the 2006 incarnation of Checkmate, a series written by the great Greg Rucka. This version leans heavily into espionage drama, reimaginging characters such as the original Green Lantern Alan Scott into spymasters who mistrust even their fellow Checkmate agents. Gunn has already integrated Sasha Bordeaux from this run into his Peacemaker series. Surely, more elements are not far behind.

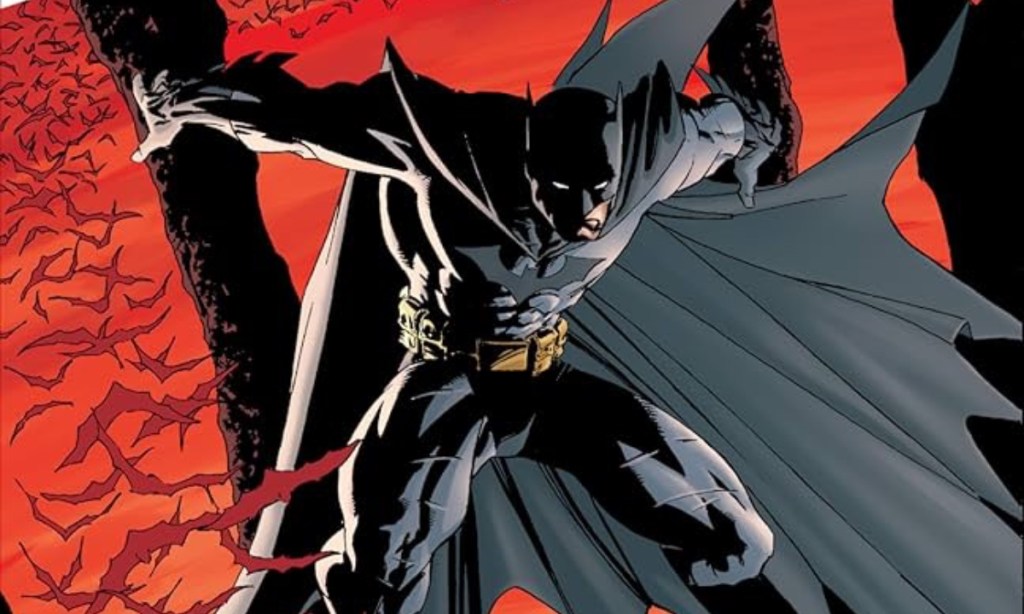

Batman by Grant Morrison (2006–2013)

When he initially announced his Superman film, Gunn used several images from Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely’s All-Star Superman. And yet, when Superman finally hit theaters, it included no images or scenes from that comic, but still felt very much like a proper adaptation of that comic.

One has to wonder if the same will be true of The Brave and the Bold, which Gunn has promoted with images from Batman and Son, a pivotal storyline from Morrison’s Batman run. In addition to introducing the Damian Wayne version of Robin, the son of Bruce Wayne who is a ninja assassin and also the world’s snottiest thirteen-year-old, Morrison’s Batman run imagined the Dark Knight as a jet-setting adventurer in the vein of James Bond. If Gunn draws from these comics for the DCU, then we will get a clear departure from the grounded Caped Crusader in Matt Reeves’s The Batman.

Mister Miracle (2017–2019)

Thus far, Gunn has avoided direct adaptations of comic books. Even Supergirl, which appears to draw fairly heavily from Supergirl: Woman of Tomorrow has its revisions, such as a dustier color palette and the inclusion of Lobo. However, if there’s one series that seems to be more or less following the source material, it’s the upcoming Mister Miracle animated series.

Which makes sense, because the series was written by Tom King, and King is a member of Gunn’s DCU writers room. Mister Miracle takes the vast New Gods mythology that Jack Kirby devised in the 1970s and turns it into a study on depression. Overbearing as that may sound to some, King and artist Mitch Gerads—whose distinctive style will hopefully be recreated (and he will be compensated) for the show—find moments of humor, such as a sequence involving the ultimate evil Darkseid and a veggie platter.

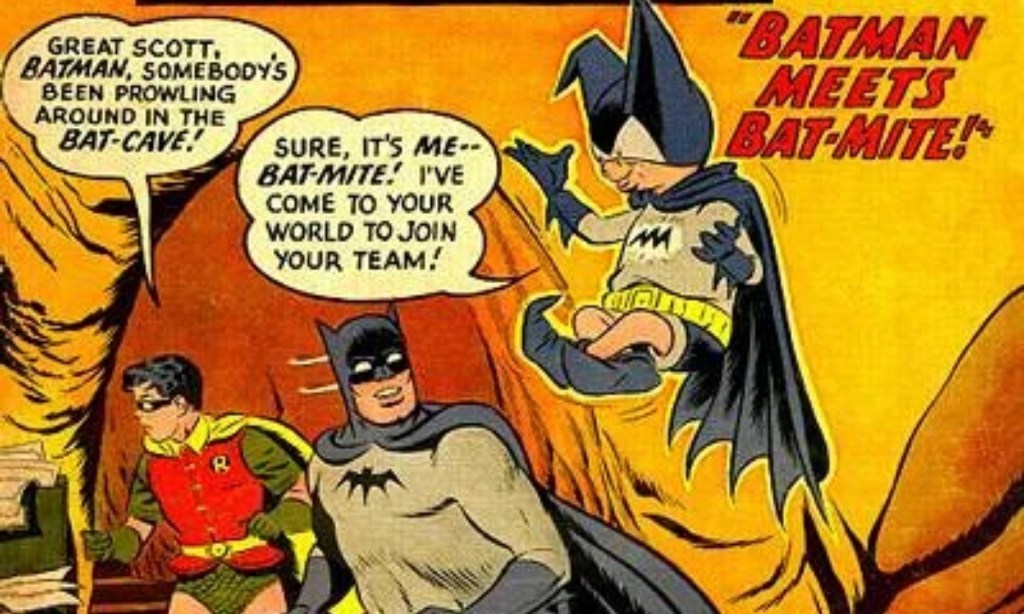

“Batman Meets Bat-Mite,” Detective Comics #267 (1959)

As he told us at Den of Geek, Gunn’s favorite DC character is Bat-Mite, a troublesome imp who loves Batman. Although he’s managed to work imps into both Peacemaker and Superman, he still hasn’t figured out how to bring in Bat-Mite.

The most obvious avenue would be following the path that Grant Morrison set in their Batman run, in which Bat-Mite was a hallucination that Bruce Wayne built into his psyche should his mind be compromised. But we can’t help but hope that Gunn goes way back to the character’s origin in 1959, when he was just a superfan who arrived from another dimension to annoy the Caped Crusader.