Remembering Ringo Starr’s Forgotten Acting Career After the Beatles

From counterculture sex farces to classic children’s programming, Ringo Starr hit every genre long after his stint as the Beatles’ leading man.

“They’re gonna put me in the movies,” Ringo Starr sang on The Ed Sullivan Show as the Beatles covered Buck Owens’ hit “Act Naturally.” The 1965 appearance featured songs from the group’s new film, Help!, director Richard Lester’s send-up of James Bond movies and other elements of spymania, as well as a follow-up to the greatest jukebox movie ever made, A Hard Day’s Night (1964). Both films put the rhythm up front. It was natural.

Prior to the nationally broadcast live performance, Starr prepared the audience by introducing himself as “all nervous and out of tune,” and smiled embarrassedly without missing or slowing a beat through his propulsive country swing. Starr was a natural performer, a locally famous beat-keeper in Liverpool before joining the Beatles, whose rhythm patterns had a character which set him apart from other drummers. His beats had personality. As the song says, he played the parts so well that he barely needed rehearsing for his first foray into a featured scene in a feature film.

Ringo was hungover when filming the “deserter” scene in A Hard Day’s Night, wherein he abandons the band before final run-through to toss rocks into the River Thames and dodge soccer balls from young actor David Jansson, who is likewise a deserter from school. The script was split evenly between each Beatle, but Paul McCartney’s solo scene was cut; meanwhile Ringo’s big scene propelled what became the story, rather than function as excuses for comical asides, as pulled off brilliantly by George Harrison and John Lennon in each of their mistaken identity sequences.

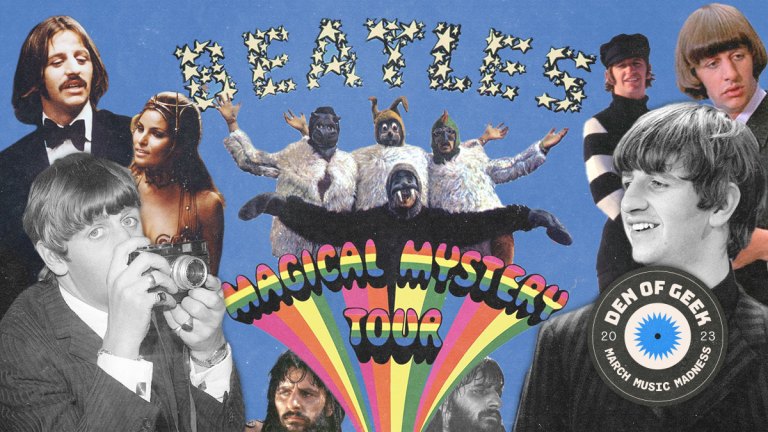

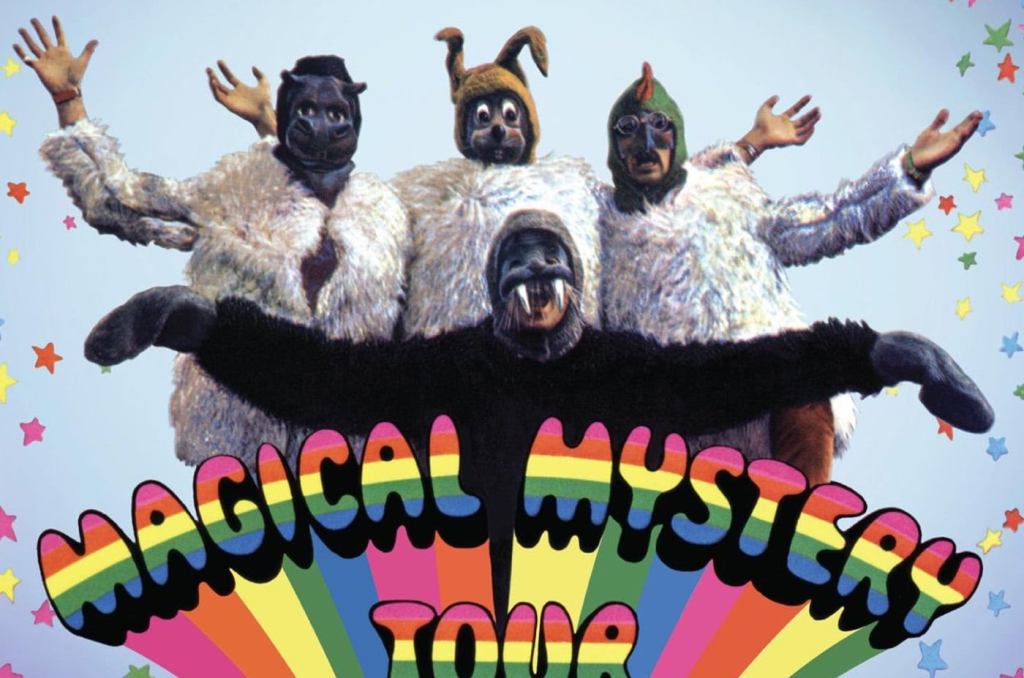

At the risk of losing a finger, Ringo is also the lead of Help! (1965), and even though he doesn’t speak the part, steers Yellow Submarine (1968). Additionally, he was director of photography for Magical Mystery Tour (1967), though each Beatle conducted individual segments. The film is a loose psychedelic road trip inspired by Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters, its experimental extravagance was fertile ground for true cinematic innovation, touted by directors like David Lynch. For a sequence accompanying “Blue Jay Way,” Ringo projected filmed clips onto Harrison’s face, creating ethereally feline double images.

“I had all the crazy lenses, all the prism lenses, and I was making slides,” Ringo says in Ringo: With a Little Help by Michael Seth Starr. “So, I knew that stuff.”

Ringo Behind the Camera and Without the Beatles

Ringo spent the first money he earned from being a Beatle on cameras and took photography seriously, not only having a number one hit with a song about a snapshot, but publishing a limited-edition book, Photograph. Filmed in vibrant psychedelia, Magical Mystery Tour aired in black and white as a TV special, spoiling the experience for critics. With the color restored, it is another film entirely, and some of the segments are as cinematically ambitious as a motion picture musical could offer. The cinematography accompanying “I Am the Walrus” alone is as visually evocative as anything in The Wizard of Oz.

Starr would go on to direct Born to Boogie, the 1972 Marc Bolan and T-Rex documentary feature, for Apple Films. The movie is freewheeling, fun and features a young Elton John pounding the ivories to pack extra punch on the song “Before the Revolution.” Starr, the director, nods to the mock-documentary feel of his first acting feature, replacing Beatlemania with T-Rextacy.

Lester’s romps through the early Beatlesmania were best viewed through the emotionally naked eyes of Starr. He hid nothing, and had an innate wit along with a knack for mild physical comedy. Lester also directed Lennon as Private Gripweed in his next project, the 1966 anti-military satire How I Won The War. Lennon himself would also go on to direct experimental films with Yoko Ono, but Ringo made art with movie stars.

Directed by Christian Marquand in 1968, Candy boasts a stellar cast including Marlon Brando, Richard Burton, James Coburn, John Astin, John Huston, Walter Matthau, and Anita Pallenberg. It stars Ewa Aulin as Candy Christian, the embodiment of the free-for-all love movement of the counterculture. As the piously repressed Emmanuel, Ringo’s first non-Beatle role saddles him with a sad scouse-inflected Mexican accent. It rewards his character with a religiously fervent shared sexual epiphany on a pool table, with voyeurs ogling the events or gaping at the scene.

As Candy moves its story through erotic encounters, the cut version is a mess. However, the full two-hour film, with a screenplay by Buck Henry, is a satiric masterpiece. It was adapted from the 1958 novel by Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg. Ringo’s next project would also come from Southern.

And Now for Something Completely Different… and Magic

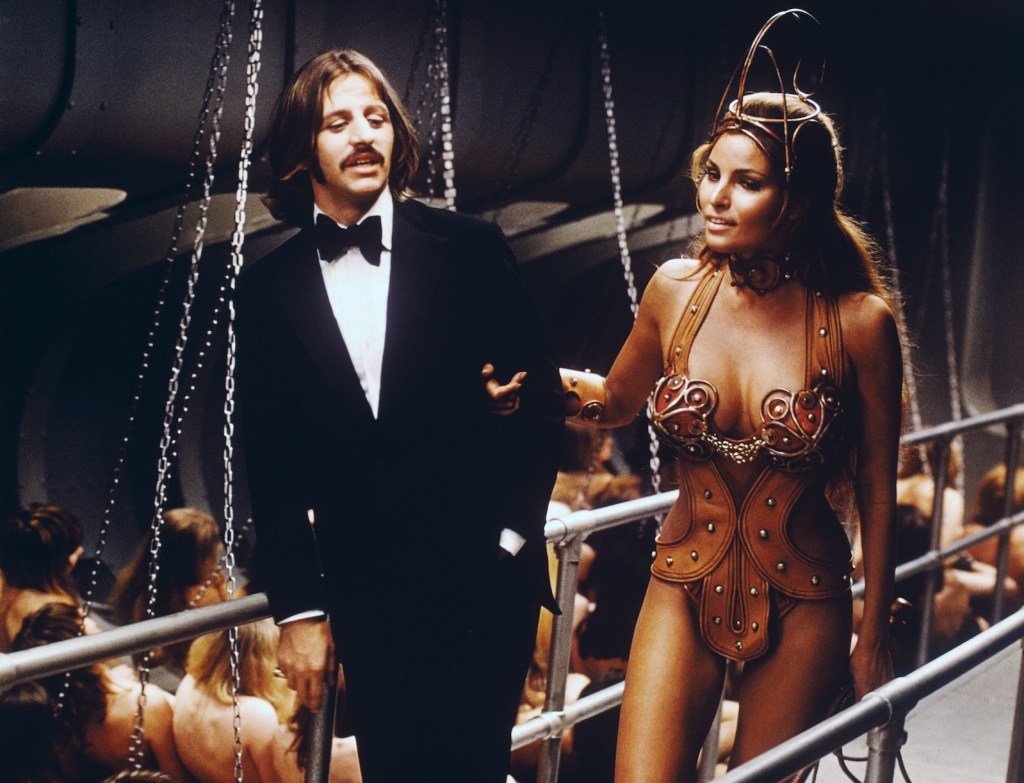

“If you want it, here it is, come and get it,” the Welsh rock band Badfinger sings during the opening of The Magic Christian (1969), an absurdist comedy and stinging evisceration of all things capitalistic. The aforementioned song was written by McCartney, and Lennon was the filmmakers’ initial dream casting for the central role of Youngman Grand, a homeless drifter transformed into a posh man of means. However, Ringo was the one who landed the part of the laconic enabler, capturing the jaded mischief of his generation effortlessly. Peter Sellers’ Sir Guy Grand does all the heavy-lifting, adopting the vagrant, and teaching “everyone has their price.”

Magic Christian director Joseph McGrath filled the scenes with a cast of affordably eccentric celebrities. Christopher Lee takes a small bite of celluloid as a vampire while Raquel Welch raises welts as an S&M priestess with a whip smart delivery. Yul Brynner pulls off a cameo, and a wig, as an over-the-top transvestite cabaret singer. Monty Python’s John Cleese plays a Sotheby’s auction director, and Graham Chapman can be seen in the rowing segment. The pair co-wrote an early version of the script.

Starr, along with singer Lulu, barely appeared on an episode of Monty Python’s Flying Circus on Oct. 26, 1972, being introduced by Michael Palin’s tramp just as the end credit theme begins. In 1974, Chapman and Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy writer Douglas Adams crafted a science fiction comedy script for Starr to coincide with his album Goodnight Vienna. With parts for many of the Python troupe, and ending with the accidental destruction of the universe, the one-hour TV special was passed on by all the American TV networks. It is available to read in OJRIL: The Completely Incomplete Graham Chapman (1999).

Harrison, of course, is noted for starting the production company HandMade Films to produce Monty Python and the Holy Grail, and would also mock his Beatle past with the combined troupes of Monty Python and Saturday Night Live’s original Not Ready for Primetime Players for The Rutles: All You Need Is Cash in 1978. Starr’s NBC special, Ringo, from that year, begins with Harrison giving a mock press conference tying the realities between the two tales. Starr played two roles in his “Prince and the Pauper” takeoff; he had already hit the heights of cynical rock star sendups.

Hollywood Vampires, Evil Dwarves, and Hot Nuns

Written by Frank Zappa, who co-directed with Tony Palmer, 200 Motels premiered at the Plaza Theatre in New York City, on Oct. 29, 1971. Movie critics responded by acting like rock stars throwing TV sets out of hotel windows. They didn’t understand the plot, couldn’t dance to the rhythmically challenging music, and were blinded by the frenetic light show. Like Magical Mystery Tour, the handmade movie broke many new technological grounds. It was the first feature film shot entirely on video and was edited using every special effect available.

Ringo plays Larry the Dwarf, who is actually an evil version of Zappa. Starr may not sound like Frank, but he captures his mannerisms and brings a lot of energy into the part. Ringo took on the role to “hang out with musicians,” according to his commentary on the 200 Motels 50th Anniversary Edition. Renowned for keeping time with other drummers, Ringo told Frank to cast Keith Moon of the rock band The Who as “the Hot Nun.” His next film, documenting the first rock benefit concert, The Concert for Bangladesh, would see him seated side-by-side with drummer Jim Keltner.

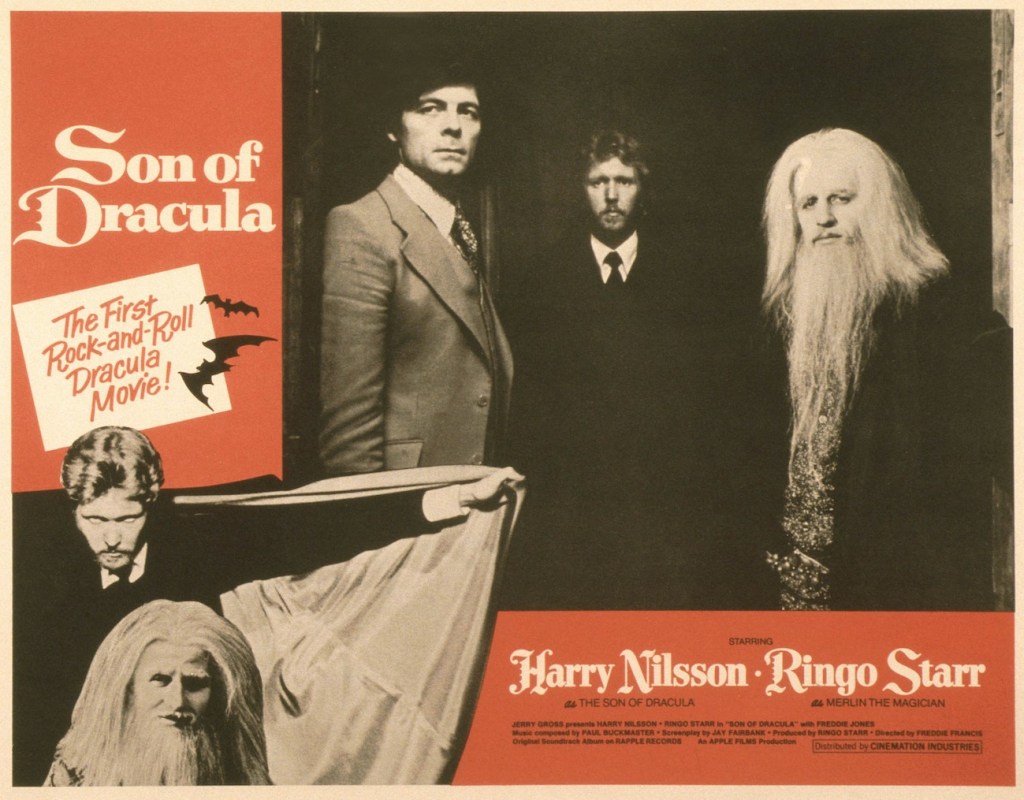

Keltner and Moon would be joined by John Bonham of Led Zeppelin as alternating drummers for Count Downe’s (Harry Nilsson) band in Son of Dracula (1974), made shortly after 200 Motels but never officially released. We can also see Peter Frampton, Klaus Voormann, and a glimpse of Leon Russell backing Nilsson, who was playing the only son of the recently assassinated Dracula. The Hammer Horror-produced musical monster comedy makes proper use of the props and settings of the studio’s intimidating sets. They have great acoustics, and enough space for a whole band, and when they kick out the jams this film finds its most frightful grooves.

Neither hellish nor heavenly spawned, Son of Dracula feels like it was made at the popular-among-rock stars nightclub Tramps, with musical performances taking up a major bulk of the screen time. Son of Dracula was directed by Freddie Francis, who made Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (1968), and possibly the best of the Hammer Dracula offerings, The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1973). He employed some of the production house’s regular troupe for the rock schlock spook-fest, including screenwriting actor Jennifer Jayne. Freddie Jones meanwhile plays Baron Frankenstein, busy plotting a coup at the powerful house of Dracula.

Though it shares a title, the creature feature is not in the same universe as Universal’s Son of Dracula (1943), with Lon Chaney Jr. as Count Dracula. Nilsson eschews the traditional portrayals of Bela Lugosi and Christopher Lee in his caped serenader, who is more brooding than frightening. Count Downe wants to give up his eternal powers and bloodlust for a chance at true love, and Ringo’s Merlin has the astronomical, alchemical, and astrological means to perform the transformation.

Starr brings wise optimism and jaded menace to his ancient wizard, especially when he weaves his magic while enjoying a game of pool. Personally, this writer believes Ringo should have stepped into the late Richard Harris’ Dumbledore role in the Harry Potter franchise.

Not everything has to have a point though. Starr made most of his movies for fun, an excuse to hang out with friends and dabble in visual arts. Son of Dracula works best as an allegory to the nighttime escapades of rock gods between takes. It is an outgrowth of the Hollywood Vampires, a group of musicians making noise in LA, including Lennon, Alice Cooper, and a rotating roster of rock’s nocturnal session players.

Starr’s work with Nilsson further yielded a children’s classic, The Point. For the initial Feb. 2, 1971 broadcast as an ABC Movie of the Week, Dustin Hoffman voiced the father of the pointless son living in a pointed community. Starr rerecorded the father’s role for further airings, and VHS and DVD releases, and exhibits an instinctive gift for voice work, bringing a reassuring emotional center to a thought-provoking burst through the logic of natural order. There was nothing remotely comforting in Ringo’s next role.

Ringo’s Serious Acting Chops and Riding Crops

Ferdinando Baldi’s 1971 Spaghetti Western, Blindman, stars Tony Anthony as Ciego, a sightless gunman paid to escort mail-order brides to miners. Relaxed and improvisational, Blindman is as raw as a Sam Peckinpaw shoot-em-up. Starr gives an enthusiastically sadistic performance, too, as the villain Candy. The bandito shoots off the head of a snake, happily knifes a harmless old codger with only a momentary glare of malice, and tortures the hero with ingeniously back-breaking rope drops. As much as this is a western adventure, Starr gives a deeply nuanced internal interpretation of the physically impetuous head of the gang of desperate, and libidinous, thieves.

“I knew Ringo could act, but I wasn’t sure how well he could act because it wasn’t sort of the zany, madcap films that the Beatles had made,” musician and actor David Essex says in Ringo: With a Little Help. “But pretty soon I saw that he was a natural and truthful actor.” That’ll Be the Day (1973) is one of the best period films of 1970s British cinema. Essex plays Jim MacLaine, a roustabout who discovers music, very loosely based on Lennon.

Starr plays Mike, a teddy boy with a gift of gab, a bird in each hand, and a weakness for bumper-cars, working at a holiday camp during the early wave of rock and roll. He does alright on the dance floor, if the band on stage is steady, and shakes off his disappointment visibly when they’re not. The performance is completely natural, and won acclaim from critics and fans alike. Ringo skipped the sequel Stardust (1974) while Moon contained his manic energy long enough to reprise his role as the drummer in Essex’s band.

Screwing with Classics, and Living a Legend

Moon’s bandmate, singer Roger Daltrey, was also primed for matinee idolatry, and Ringo was on hand to condemn it with his blessing. Lisztomania (1975) is director Ken Russell’s romp through the many loves of Hungarian Romantic composer Franz Liszt. An Elvis of his time, he was one of the first master pianists to play for the common people as much as the rich, and enjoy the fruits of both worlds.

Starr plays the Pope, whose papal throne penetrates Liszt’s bedroom while he is in flagrante delicto.

“I was forced to have carnal relations with this woman at gunpoint,” Daltrey’s prodigal Liszt protests. “We’ve all been there,” God’s representative on Earth responds, along with other blasphemous realities. Even though Yes keyboardist Rick Wakeman lent his classically trained fingers to the soundtrack, and has a cameo, Liszt’s work is sadly underused. The film is chaotic and anarchic, fun for fans of counterculture excess, and the opening run of a carnal arpeggio.

A few years after Lisztomania, Starr was invited to come up and see a girl, sometime. He had more than a pair of drumsticks in his pocket.

Screen legend, Broadway star, and cultural pioneer Mae West was 89 when she broke the last remaining cinematic sexual taboo as the 28-year-old Marlo Manners: she played a sexually empowered older woman. This is still a criminally under-examined topic today, but West wrote candidly about it in 1978 with Sextette, a movie that puts the screw in screwball comedies.

Starr, who plays West’s “husband number four” to Timothy Dalton’s “husband number six,” made the film as an excuse to hang out with West. The film is structured like an old-fashioned Hollywood romp. Ringo’s theatrical take on the eccentric, petty-thieving European film director character Laslo Karolny would have worked seamlessly in a vintage black and white, light feature. George Raft, whose career intertwined with West’s from their stage beginnings, puts in a cameo. Alice Cooper and Dom DeLuise also lend comic relief to West’s last film.

Something for the Kids

Set in One Zillion B.C., on Oct. 9 (Lennon’s birthday), Caveman (1981) may seem dated but it’s a traditional slapstick comedy made for all ages, and best enjoyed by stoned children. Written and directed by Carl Gottlieb, Caveman is almost a silent film, as most of the dialogue is done in grunts and groans. The stop-motion effects were created by the resourceful Jim Danforth, who created the creatures for the 1974 softcore sci-fi spoof, Flesh Gordon.

Ringo portrays Atouk, an early man out to win the love of alpha female Lana, played by The Spy Who Loved Me’s Barbara Bach (and shortly afterward Starr’s real-life wife!). The pair met on Caveman and would soon reunite onscreen as trendy trans-Atlantic fashion designers Robin and Vanessa Valerian in NBC’s miniseries Princess Daisy (1983), based on the novel by Judith Krantz. Starr would wind down his onscreen performances around the same time he appeared in Paul McCartney’s Give My Regards to Broad Street in 1984.

“I was too busy doing other stuff,” Starr said in Ringo: With a Little Help. “I realized that there’s enough actors; I’m a musician.”

That didn’t stop Starr from stirring up an all-star soup with his turn as the Mock Turtle in the 1985 TV movie adaptation of Alice in Wonderland. Starr has always had a large following among very young audiences. ABC ran Saturday morning cartoon series The Beatles from 1965 to 1967, and children were late for school every morning when it ran in weekday syndication until 1969. New generations still thrill at discovering Yellow Submarine, and The Point, or catching Ringo as the narrator and ultimately Mr. Conductor on Thomas the Tank Engine and Friends (1984-86), and Shining Time Station (1989).

Starr was the first Beatle to voice himself on The Simpsons, personally answering a fan letter Marge sent as a school girl and inspiring her to paint like she’s never painted before, a nude Mr. Burns; he played the Mummy on the 1998 “Good Will Haunting” episode of Sabrina the Teenage Witch; he also voiced flamboyant mathematician Fibonacci Sequins, one of Townsville, USA’s most notable notables on the 2014 reboot of The Powerpuff Girls. He even recorded a single, “I wanna be a Powerpuff Girl.”

Starr’s cinematic output was as eclectic as the music made by the band which got him famous. He played in big production flops and independent groundbreakers, ribald sexual comedies, and classics for all ages. Ringo may not have been ideally cast on the screen, but he always delivered a unique portrayal. Just like his beats, and the pauses which propel the rhythms as energetically as his fills, Ringo’s acting is imbued with his individual personality.