The Concert for Bangladesh Set the Standard for Benefit Concerts

Fifty years later, George Harrison’s call for relief informs humanitarian efforts as much as it entertains the ears.

The Beatles are credited with a lot of “firsts” in rock history. They were the first band to play stadium concerts, put intentional feedback, backwards instrumentation, and faded introductions into songs. Because of their ever-experimental guitarist, they were also the first rock band to put sitar and tamboura drones in pop rock and perform the first Indian modality prog piece. George Harrison didn’t stop expanding possibilities away from his bandmates. His first solo release after The Beatles’ break up, All Things Must Pass – which will have a celebratory remix release this week, was the first triple album coming from a single act in rock. In 1971, his Concert for Bangladesh was the first rock benefit concert.

The Aug. 1, 1971 show, and subsequent record and film, set the standard for musical contributions to charity. Mistakes were made, and Harrison himself paid out to fix them, teaching a valuable lesson for rock benefits to follow. But it all began very personally. “My friend came to me, sadness in his eyes, and told me that he wanted help before his country dies,” Harrison sings on the song “Bangladesh.” It is an almost verbatim version of the truth.

The Beatles’ Apple Films were producing Raga, a documentary about the renowned sitar virtuoso Ravi Shankar. In the spring of 1971, Harrison and Shankar were in Los Angeles working on its soundtrack. Shankar, a Bengali, told Harrison about things in his country. India and Pakistan were divided into two independent nations in 1947. East Pakistan declared independence, and became the People’s Republic of Bangladesh on April 17, 1971. This prompted a massive wave of migration, with between 300,000 and 3 million relocating to the mostly-Hindu nation. The move was violent, and it was reported 400,000 women were raped by Pakistani military personnel and Islamist militias, according to Smithsonian Magazine. The crisis deepened when the 1970 Bhola cyclone, floods and famine created a humanitarian disaster.

Shankar wanted to draw attention to the situation through a benefit concert. He was hoping Harrison or actor Peter Sellers might introduce the show. Shankar believed he could raise about $25,000 for the refugees. Harrison had a better idea.

My friend came to me

Harrison met Shankar at a dinner party for the North London Asian Music Circle in 1966, a year after the guitarist first picked up a sitar while the Beatles were filming Help!. Harrison brought the instrument into the studio to bring an exotic feel to John Lennon’s “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)” from the Rubber Soul album. Upon hearing it at the time, Shankar, one of India’s most venerated musicians, told a reporter “If George Harrison wants to play the sitar, why does he not learn it properly?” Harrison took him up on it, and Shankar schooled him on melodic structure and technique, but also noted the importance of the instrument’s part in spiritual discipline.

Harrison’s spiritually infused All Things Must Pass and its lead single, “My Sweet Lord,” both spent weeks at the number one spot on the charts. He had been writing with Bob Dylan, and playing with Eric Clapton and Delaney & Bonnie. “Straightaway I thought of the John Lennon aspect of it, which was: film it, and make a record of it, and, you know, let’s make a million dollars,” Harrison said, according to George Harrison: Interviews and Encounters by Ashley Kahn.

Lennon wrote a song for breakfast, recorded it for lunch and copies were pressed shortly after dinner with the Plastic Ono single “Instant Karma.” Harrison played guitar on the song, and it was produced by the studio legend Phil Spector, who would ultimately run the sound board and record the album The Concert for Bangladesh. Spector didn’t get to see the show. He was stationed in the Record Plant truck getting the perfect mix of a full horn section, two drummers, almost half a dozen guitarists, and over a dozen background singers.

A Beatles Reunion?

Harrison’s initial idea was to recruit the other Beatles. Paul McCartney, who had just put Wings together, initially agreed, if he and Lennon also performed separate solo sets. Lennon first balked at performing because Harrison didn’t want Yoko Ono to perform, then agreed, but flew to Paris after the decision led to domestic distress. He missed the show, and it caused a rift between the two former bandmates. McCartney ultimately backed out, citing the legal problems of being in the same room as Allen Klein.

Harrison didn’t have to ask Ringo Starr. According to reports, Starr was nervous about playing in front of an audience, but if you look at the footage of the two drummers playing, mostly in tandem, while joking with each other, it is plain he just wanted Jim Keltner’s company. Harrison gets to trade guitar licks with Clapton, Davis, Don Preston, and Ham. Starr and Keltner throw their own percussive party, doubling their beats in beautiful unity. Keltner held back his hi-hat cymbal on the two and four, a technique Levon Helm of the Band used, so he’d never step on Ringo’s backbeat. Starr visibly enjoys the freedom of new sound equipment to throw in all the fills.

Awaiting on Us All

Harrison began recruiting friends to play the one-time only concert in April, and had commitments by June. All the players agreed to perform without a fee. He also arranged for a film and recording to be made of the event, to add to the proceeds which would go toward the refugees. According to Pattie Boyd Harrison, George consulted an astrologer before he finally booked August 1 at Madison Square Garden. Tickets were set at $10 or less, so the show sold out in a few hours, and a second show was added.

The musicians rehearsed in a space above Carnegie Hall for about a week, but because of the various musicians’ schedules, the first time the group played together was at the show. Clapton was invited to be the lead guitarist, but missed rehearsals because the low-grade heroin he was supplied forced him to go two days cold turkey, he admits in his book Clapton: The Autobiography. Deeming the guitar god possibly unreliable, George also recruited Taj Mahal’s guitarist Jesse Ed Davis, who could move easily through playing rhythm, lead, slide, country, and jazz. In the book Do You Feel Like I Do, Peter Frampton reveals he could, or should, have been on that stage as well. He mistook his invitation as one to be in the audience. Harrison reportedly turned down offers from Mick Jagger and David Crosby to appear.

The 24-piece band included Klaus Voormann on bass, Pete Ham, Tom Evans, and Joey Molland on acoustic guitars, and Mike Gibbins on tambourine and maracas. Don Preston played electric guitar and Carl Radle played bass for the song “Jumpin’ Jack Flash/Young Blood.” The stage also accommodated the Hollywood Horns, which was its arranger Jim Horn, as well as Jackie Kelso, Allan Beutler on saxophones, Chuck Findley and Ollie Mitchell on trumpets and Lou McCreary on trombone. The Soul Choir included singers Claudia Lennear, Joe Greene, Jeanie Greene, Marlin Greene, Dolores Hall, and its organizer, songwriter Don Nix.

Pianist Leon Russell was the musical director, just as he had been on Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs and Englishmen tour, which Harrison and Clapton played on. Oklahoma-born legend Russell had been an essential part of The Wrecking Crew of Los Angeles studio musicians as well as an important brick in Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound. He played on thousands of recordings, including piano on “Strangers in the Night” by Frank Sinatra.

“Have we forgotten anybody,” Harrison asks the audience after introducing the band mid-show. “We’ve forgotten Billy Preston.” The Beatles history with Preston goes all the way back to their early tours, just before megastardom. Preston played organ in the ensemble which backed Little Richard, who had the Beatles as an opening act. He was also the musician Harrison called in during the Beatles’ “Get Back” recording sessions. Preston, who’d also played with Russell on the pop music series Shindig! in May, 1965, brought more than an electrifying organ to the main act’s arsenal of sound. Harrison produced several of Preston’s albums and studied the idiom of Gospel music to capture the master player’s work blending it into secular funk overdrive. The collaboration between the two musicians is evident all over All Things Must Pass, which blurred the lines between the eastern and western religions by mixing modalities. The all-star rock concert to beat all all-star rock concerts was a spiritual revival in more ways than one.

The Performance

The shows open like Hindu pujas with traditional Indian music. Before the performance Harrison introduced the players, Shankar on sitar, Ali Akbar Khan on sarod, Kamala Chakravarty on tambura, and Alla Rakha on tabla. He explained how Indian music was more serious than the rock they’d be enjoying later, and to give it respectful concentration. Shankar requested the audience not smoke during their segment, as the ragas sought to help them “feel the agony and also the pain and a lot of sad happenings in Bangladesh and also the refugees who have come to India.”

After the musicians calibrated their tones, the audience burst into applause. “Thank you, if you appreciate the tuning so much, I hope you will enjoy the playing more,” Shankar smiled from the stage, before launching into “Bangla Dhun.” It begins with an improvisation on the raga’s melodic themes before the tambura drone and tabla push the rhythms until they explode by the end of the piece. The audience wasn’t respectful. They were floored. The rock audience who went to see fingers fly got to see stringed interplay between Ravi and Ali which was every bit as good as the guitar duel between Harrison and Clapton at the end of that night’s performance of “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.”

It is Harrison’s evening and he opens it himself. The spotlight illuminates his white two-piece suit with the Om symbol, and the first sounds the audience hear is his single guitar playing the opening riff of “Wah-Wah,” before Davis doubles it and the band kicks in. The Concert for Bangladesh was the first time Harrison played songs from All Things Must Pass live, but the audience was already familiar. The live version of “My Sweet Lord” is as uplifting as the studio recording. A particularly beautiful moment catches Harrison losing himself in the mantra towards the end of the song.

George blows a line in “Awaiting on You All,” but who cares, he’s ripping it out with a positively religious fervor. Preston takes on the spirit, and lifts it further with the power of gospel in “That’s the Way God Planned It.” Not content with electrifying his congregation through organ and voice, Preston gets up on his feet in an impromptu celebratory dance, not even Harrison saw coming. It is harmonic euphoria with heavenly promise.

Ringo brings things back to the Garden, grounding the proceedings with jubilant blues. The drummer paid his dues, and is enjoying its fruits as he kids around with Keltner after scatting over forgotten lyrics. His chosen tune, “It Don’t Come Easy,” was produced by Harrison, spent time on the top five of the charts and was still riding the high hat of heavy radio rotation.

“Beware of Darkness” bridges east and west, gospel and Hindu, rock and roll and country and western. Harrison begins the song, faithful to the album version, until Leon infuses a verse with melodic possibilities in a mere tease of things to come. Harrison’s plaintive rendition of “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” is wrought with personal demons. He gets those behind him when he and Clapton trade improvisational riffs to close the song. They duck, they weave, punch every modal challenge with the counterpunch of blues purism.

Rhythm and blues is at its most authentic when Leon Russell invokes his trinity for a roof blowing medley of The Rolling Stones’ “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” and the song Leiber and Stoller wrote for the Coasters: “Youngblood.” Russell turns Madison Square Garden into a tent revival orgy, preaching to the choir with exhilarating call and response exaltations which encapsulate the subtle motif of the day’s performances. This is where the show hits its jubilant peak, and marks the time to exhale.

“Here Comes the Sun” is George’s most intimate and assured performance of the evening. Blanketed only subtly by Don Nix’s gospel choir, George and Badfinger’s Pete Ham duet on acoustic guitars, filling their intricate unison fingerpicking with different configurations, and never missing a run on the prog time changes masquerading as seamless simplicity. The sparse arrangement takes nothing away from the majesty of the original recording, it augments it by transforming the space between notes into exultant expectation.

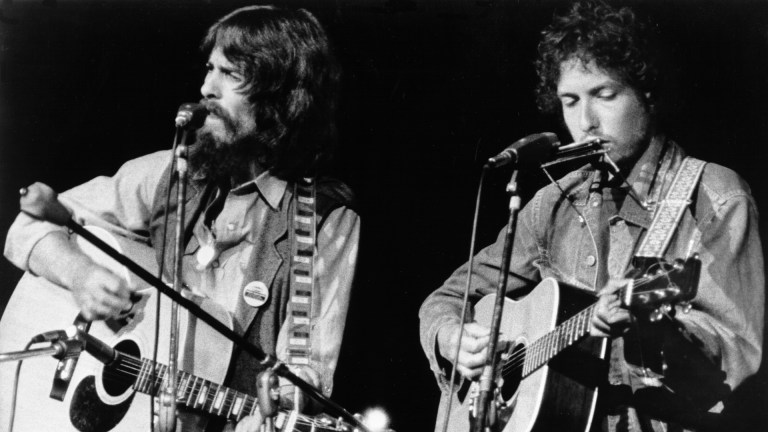

George was as surprised as his next guest was to be announced to the stage. As Harrison strapped on his white Fender Stratocaster, he checked the wings before bringing “on a friend of us all, Mr. Bob Dylan.” Even though the singer’s history of appearing at historic events went back to his performance at the March on Washington, no one knew if Dylan was going to make the show until he walked on the stage. It took Harrison’s cajoling to get Dylan to play the Isle of Wight in 1969, and he was happy playing Napoleon in rags, exiled in Woodstock since his motorcycle crash.

While Dylan had shown up at rehearsal, Spector got concerned when heard the musical icon had been bicycle riding all morning. Harrison had just asked if Bob would play “Blowin’ in The Wind” at the show, and Dylan hurled back “You gonna do ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand?’” But after handpicking Starr on tambourine and Russell, who strapped on Voormann’s bass, to augment his rhythm guitar and Harrison’s slide, not only did Bob blow wind through his shoulder-mounted harmonica, he strummed through his old favorite “Mr. Tambourine Man,” and dipped into folk blues with “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry.” Harrison’s guitar lines slide delicately around Dylan’s vocals on “Love Minus Zero/No Limit,” while Russell and Harrison blanket his rendition of “Just Like A Woman” with harmony as well as irony. It may be the finest rendition of the song.

As beautiful and exquisitely rendered as it is, the best part of “Something” is when Harrison gets lost in his guitar playing to the detriment of his vocals and cracks himself up. It’s very visible in the film, and it lifts the performance because it almost shocks him into enjoying it and how comfortable he is performing it.

The evening show had a slightly different set list and sequence. “Hear Me Lord” was dropped. Dylan played “Mr. Tambourine Man” in place of “Love Minus Zero/No Limit.” But both ended with the song written for the event, “Bangladesh.” Anchored by Leon Russel’s propulsive and suspenseful A minor, it is a self-effacing call for bread. Harrison freely admits he couldn’t feel the pain, and suggests that’s what makes it so personal. He leaves the band and the audience alone to jam out the end of the song, as if an invisible plate were being passed by spirited hands.

The concert raised $243,418.50, which was given to UNICEF, who gave Shankar and Harrison their “Child Is the Father of Man” award for fundraising. The George Harrison Fund for UNICEF continues to this day.

But in the rush of putting the Concert for Bangladesh together, Harrison hadn’t specified a charity and lost any charitable tax breaks. A lot of money went missing, and an inordinate amount went to taxes. Harrison paid his own money to maintain the fund. The concert record, which was the second triple album in a row from Harrison, topped charts and won the Grammy for Album of the Year, but that also didn’t stop the delays in money being sent to help the Bangladeshi refugees. Years later when Bob Geldof reached out for tips for the 1985 Live Aid concert event, Harrison advised “Do your homework.” It was an important lesson. Nearly $12 million was tied up in an Internal Revenue Service escrow account for 11 years because organizers didn’t apply for tax-exempt status. Harrison’s initial attempt laid bare exactly what had to be done not only to stage a major music benefit concert for a humanitarian cause, but how to get the money where it belonged.

The Concert for Bangladesh album was released on Dec. 20, 1971. The film was released in the U.S. on March 23, 1972. They can be enjoyed together or separately. Each of the two are high marks reached for live albums or films, there is not a moment of downtime, and all the notes are in harmony.

All Things Must Pass 50th Anniversary Edition will be available on Aug. 6.