Christopher Nolan Movies Ranked from Worst to Best (Including Oppenheimer)

From Memento to Oppenheimer, and all the Dark Knights in between, we rank the works of one of modern cinema’s loudest voices, Christopher Nolan.

Christopher Nolan remains one of the most significant filmmakers of the 21st century. The mere fact that stating this aloud invites a bit of controversy underlines how outsized a footprint the writer-director has left during the first 25 years of his career. Celebrated by some as a formative auteur in the lives of young cineastes, and derided by others as the patron saint of “film bros” who devour hyper-masculine Hollywood spectacle (particularly if it features capes), Nolan’s already built a formidable and debated legacy.

But in the summer of 2023, his impact was crystalized again when Nolan convinced one of the ever increasingly risk-averse Hollywood studios to invest more than $100 million into an R-rated, three-hour, and existentially despairing biopic, and then released it at the height of summer. That the movie opened bigger than most of the year’s alleged blockbusters, and bigger than any Nolan film not starring Batman, is a testament to the mystique this singular storyteller has cultivated with audiences. Only a handful of other directors have developed such a wide following by melding artistic intent with shrewd commercial sensibilities.

But if Oppenheimer is something of a culmination for the last quarter-century of output from the filmmaker, does that mean it’s his best? And where do the other 11 films he’s helmed rank? We have some ideas….

12. Following (1998)

Christopher Nolan’s first film was a production the young talent shot with his wife and producer, Emma Thomas, and their friends on weekends. No one wanted it to conflict with their day jobs. It’s a testament, then, to Nolan’s earliest craft that you could never tell this by watching Following. However, you can definitely recognize this is a first film from a talented if still rough around the edges filmmaker.

Released when Nolan was only 28, the movie is in many ways an experiment in themes and ideas that would color the rest of the writer-director’s filmography. Like most of Nolan’s early output, it’s a neo-noir picture about the self-destructive obsession of a flawed protagonist, who in this case cannot help but pursue his desire to follow strangers home. In a narrative unspooled via nonlinear storytelling, and shot on black-and-white 16mm film stock, we are invited to likewise follow a nameless and unemployed young man (Jeremy Theobald) as he walks behind strangers for fun. The lad’s vaguely Hitchcockian voyeurism becomes his undoing, though, after he is spotted spying on the criminal underworld. Viewed today, it’s not entirely polished, and the narrative strands more knot and jumble than weave and coalesce. Still, the compelling hook of Nolan’s penchant for unconventional structure and unreliable narrators was already in place.

11. Tenet (2020)

Contentiously released during the fall of 2020 at Nolan’s insistence, Tenet positioned itself as a savior of movie houses during the pandemic. This was, in retrospect, a tall order for what is Nolan’s most ambitious action movie, as well as his most remote and exasperatingly opaque. Reappraisals have already begun, with some arguing Tenet was the director attempting to see how far he could lead audiences down the path of esoteric “vibes”—there is the famous line “don’t try to understand it, feel it”—but we’d contend Tenet remains a bridge too far.

With the conventions of modern action cinema intentionally sketched at their thinnest and most utilitarian (John David Washington’s character is simply called “The Protagonist”), Tenet nonetheless presents a dizzyingly complex world and challenging sci-fi idea in which the entropy of objects and even people can be inverted—allowing most things to travel backward in time. Yet the execution is so needlessly obtuse, and the sound design intentionally confounding, that it doesn’t matter if you understand it; the main thing you’re feeling is frustration and annoyance. There are some dazzling action set pieces, and Hoyte van Hoytema’s cinematography and Ludwig Göransson’s score are sumptuous, but even after figuring out just how many Robert Pattinsons are running around at various stages of inversion, the movie remains little more than a stylish puzzle box that’s far too pleased with its configuration.

10. Insomnia (2002)

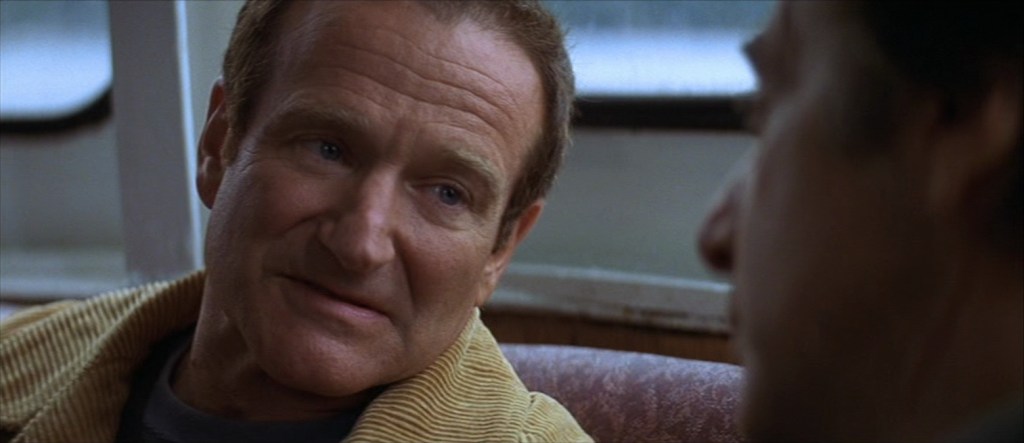

Very few directors on this side of the millennium have gotten Al Pacino to deliver a restrained and sharp performance that understands some lines can actually be underplayed to marvelous effect. Christopher Nolan is one of them thanks to his icy remake of a Norwegian film of the same name. Another excursion into neo-noir, Insomnia follows in the footsteps of many post-Se7en and Silence of the Lambs Hollywood murder procedurals, casting one movie star as the cop (Pacino) and the other as the killer (Robin Williams).

The cold-blooded cunning of Insomnia comes from the revelation that the killer is no genius, but rather a somewhat pathetic loner with a reptilian brain who, through a grim twist of luck, is able to blackmail his pursuer into becoming his accomplice. In hindsight, the film’s fascination with the duality between hero and villain was a warm-up act for The Dark Knight, but the restrained Insomnia is often more unsettling due to how calmly both actors are asked to essay their characters, with Williams making for an exceptionally soft-spoken demon, and Pacino for a compelling corrupt cop circling the drain. If the film was allowed to better breakaway from the conventions of these types of early 2000s movies, it might’ve been an actual classic instead of an absorbing, if less memorable, star vehicle from an era when studios would let stars appear in such fare.

9. Batman Begins (2005)

The placement of the Batman films on this list will undoubtedly be the most contentious thing for readers, but please understand we all think Batman Begins is a great piece of entertainment, as well as the finest superhero origin story ever produced. Told with what was at the time a shocking amount of gravitas and charm, Batman Begins recognized superhero movies as material worthy of serious cinematic consideration. Such a feat arguably had not been seen since Superman: The Movie (1978). Yet therein lies Batman Begins’ limitations.

While Nolan’s first Batman film is still the best version of any caped origin story, Batman Begins follows to a tee the formula as set down by Dick Donner in ’78. That does not take away from how confidently well-formed this film is, as well as how it offers the still best cinematic interpretation of Bruce Wayne, who is given a poignant dignity in Christian Bale’s sad eyes. Together, the director and star perform their own kind of stage illusion, convincing audiences to take a man dressed up as a Bat seriously. Somehow you buy into the idea that he is a major city’s best hope at an urban renewal. It’s an intriguing idea to turn the Caped Crusader into something of a theatrical political campaign—one whose surrogates include a murderer’s row of acting talent like Michael Caine, Gary Oldman, and Morgan Freeman. It’s also the beginning of a fruitful relationship between Nolan and Caine, the latter of whom appeared in all but one of Nolan’s following nine movies. However, many of those others were better, not least because their third acts did not descend into stock genre trappings.

8. The Dark Knight Rises (2012)

Yes, a case can be made for The Dark Knight Rises being Nolan’s second best Batman film. Often overshadowed by its direct and far superior predecessor, The Dark Knight, Rises is usually written off as the ugly duckling of the trilogy. That’s ridiculous. Told with a sweeping grandeur intentionally evocative of David Lean’s Doctor Zhivago, and prescient in its fear of a demagogue’s ability to turn an American crowd into an angry mob unleashed on the halls of power, this is the type of epic, cinematic storytelling we rarely see anymore. And it looks nothing like any other superhero movie that’s been made before or since.

Beyond its scope remains a film that also raises a still subversive and controversial question in this genre. What if the hero lets go of his pain, and learns to put away the simplistic morality of a mask? Christian Bale gives his best performance as a wounded and broken Bruce Wayne who needs to grow up before he grows old, and also before he is pulverized by one of the most memorable screen villains of the last decade, Tom Hardy’s infinitely quotable Bane. (It’s also genuinely impressive Nolan confidently keeps the Batman costume off-screen for over an hour.) Throw in Anne Hathaway’s slinkiest performance as an underrated Catwoman, as well as some stunning action sequences, and you’re left with the rare thing: a satisfying ending to a superhero story.

7. Dunkirk (2017)

Despite crossing over into the relatively well worn genre of war films, Dunkirk proved to be Nolan’s most experimental project to date. Told with a clockmaker’s precision and blocked with what might be the director’s most painterly compositions, Dunkirk foregoes anything in the way of modern cinematic storytelling, particularly at Hollywood studios, in favor of a stripped down and overtly challenging narrative structure. There are no character names (at least any you’ll remember), scenes of audience-aiding exposition (one of the weaker elements in Nolan’s scripts), or nearly any dialogue at all for that matter.

Instead Nolan relies on a visceral film language to convey all the important information through imagery. If not for its bombastic sound design and Hans Zimmer’s propulsive score, Dunkirk could be a silent movie, albeit a unique one since it’s told on three parallel timelines that converge during the darkest hour of Britain’s war effort in WWII: getting 338,000 soldiers off French shores before the Nazis close in. No other film has quite immersed audiences into the overpowering desperation to survive during war, nor has Nolan ever surpassed the visual poetry of Hardy standing before the burning wreckage of his plane at twilight on a beach, personifying British resolve while caught in the seeming jaws of defeat.

6. The Prestige (2006)

In what might qualify as their first self-reflective film, Chris and his brother Jonathan Nolan liberally adapt Christopher Priest’s The Prestige into a treatise on the sacrifices an artist will undergo in order to master their craft—perfecting the ability to ensnare and enrapture an audience. But like the book, it’s channeled through the enigmatic spectacle of two Victorian illusionists descending into a lifelong rivalry that turns fatal.

As these selfish magicians, Bale and Hugh Jackman do some of their most under-appreciated work, each representing one of the key sides of talent: the artist who wants to be the best in their field, and the showman who wants to be adored by the crowd. Technically, this movie is a period piece, but its urgency and zeal feels timeless. Still, the character it might most sympathize with is a definite relic of its setting, Nicola Tesla, who after watching the film now seems to have always been destined to be played by David Bowie. Tesla was a genius in his time, yet was overshadowed by the capitalistic cunning of men like Thomas Edison. Back then, Edison was called “the Wizard of Menlo Park” (inspiring another Oz-ian figure in fiction), but as realized here, Tesla was the true magician; a man who applied practical science and technology to problems until he created, as one character shudders, “real magic.”

5. Interstellar (2014)

Nolan has never been a director to hide his influences. In fact, he often wears them on his sleeve, such as when Interstellar overtly announces it will try to go beyond the monumental benchmark set by Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. If that movie’s journey ends among the moons of Jupiter, then Interstellar’s galaxy-brained odyssey begins in a wormhole just off Saturn! That’s chutzpah for you. But while Interstellar is no 2001, it is still one of the best sci-fi movies of the past 20 years and almost certainly better than you remember.

Despite the director being rightly criticized for a frequently chilly and cerebral disposition in his films, Interstellar is an aching exception to that rule, with Nolan not-so-subtly grappling with feelings of guilt and regret over leaving his kids at home for extended periods of time. For Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) and his young daughter Murph (Mackenzie Foy), this is taken to a cosmic extreme because, in order to save the human species from climate change, Coop and several other scientists travel to another galaxy where time dilation makes decades pass on Earth in the span of a day on the ship.

In terms of scope, it’s Nolan’s biggest film, and yet it is also his most intimate and sentimental—which doesn’t mean it isn’t chilling due to the horror of a parent seeing Foy age into Jessica Chastain in the blink of an eye. The movie’s also fairly wondrous, with the filmmaker and Nobel Prize-winning physicist Kip Thorne correctly hypothesizing what a black hole would look like before the real thing was photographed several years later. This is a sweeping epic that haunts, and this is in large part due to Hans Zimmer’s ecclesiastical, organ-driven score. Zimmer may not have won the Oscar that year, but it’s telling the Academy used Interstellar music for their own 90-year retrospective a few years later.

4. Memento (2000)

The lone independent film with a serious budget in the director’s oeuvre, Memento remains the cool kid answer to the question of what is the best Nolan film. And sure enough, to this day it’s a defining calling card. As the infamous neo-noir thriller “told backwards,” Memento is a marvelous magic trick where Nolan, working from a shorty story by his brother Jonathan, perfected his nonlinear filmmaking with a puzzle box that intrigues and engrosses on every rewatch.

In the film, we meet Leonard (Guy Pearce). Leonard has short-term memory loss, which means he knows no better than the audience why he’s left a note to himself to execute Teddy (Joe Pantoliano) on a crappy concrete floor. Yet as the narrative unspools mostly in reverse, we learn a great deal about Leonard’s disorienting condition, and slowly how he had a hand in crafting his own hell. In some respects, Memento is a stylish showpiece meant mostly to impress and flabbergast the audience through its narrative cleverness. That isn’t a bad thing though when the movie is this stylish and clever. Ironically, it even becomes pretty unforgettable.

3. Inception (2010)

The other sci-fi movie that’s really about moviemaking on the list, Inception has probably entered the status of a classic at this point with its now iconic narrative about chic thieves infiltrating the dreams of wealthy marks. The parallels between the team assembled by Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) and the heads of various filmmaking departments are well-known these days, but beyond the film’s meta and intertextual qualities is just a dazzling triumph in imagination and spectacle.

Cobb and his team dress like the most refined members of a James Bond ensemble, yet the actual posh worlds they move through are enticingly knotty, slowly unfurling their complexities like the M.C. Escher stairs the film pointedly duplicates. Stacking dreams atop dreams, and expanding time compressions on each layer, Inception invites audiences to get lost in its labyrinth, even as it wisely never lets go of the audience’s hand while acting as our guide. This paradox of being both convoluted and surprisingly simple may be the secret of Nolan’s appeal, and those two sensibilities are rarely in better harmony than in the one with visions of a rotating hotel hallway and the skyline of Paris folding in on top of itself as Hans Zimmer’s deconstruction of “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien” blares.

For some, this is the definitive Nolan film. And that case can definitely be made, yet the film is such a mind game—and the emotional crux between Cobb and his underwritten wife Mal (Marion Cotillard) is such a frosty center—that there are a few more we give the edge to.

2. Oppenheimer (2023)

In many respects, Oppenheimer seems to be the movie Nolan’s entire career has been building toward. Interspersed nonlinear timelines, dreamers attempting to make the visions a reality, and tales about obsessive individuals pursuing an idea until it destroys them are all realized in IMAX photography by Hoyte van Hoytema that is as intimate as it is overpowering. But by removing Nolan’s usual genre and action set-piece flourishes, and instead centering these larger fixations on the tragic story of J. Robert Oppenheimer and his creation of the atomic bomb, Oppenheimer makes Nolan’s muses more visceral and despairing than they’ve ever been before.

The terms “magic trick” and “illusion” come up a lot when discussing Nolan’s filmography, but the horror of Oppenheimer’s work is there is nothing illusory about what he created; it changed the world by (maybe) saving it from a lot more carnage in WWII but it also did so by committing a war atrocity that put us on a path to seemingly inevitable self-annihilation. Oppenheimer realizes this in his head, and the film likewise does so with Nolan blending multiple timelines in the editing like a composer utilizes an orchestra. The effect is an incredibly suspenseful panic attack that never lets go of your nerves in spite of a three-hour running time and settings rarely more grand than men sitting at a table. The ensemble is phenomenal even if (once again) the women don’t get enough to do. Nonetheless, Nolan’s frequent collaborator Cillian Murphy turns in the performance of a lifetime as Oppie, and it’s in service of a film that increasingly appears to be a masterpiece.

1. The Dark Knight (2008)

It’s almost a cliché these days to place The Dark Knight at the top of any list it appears on, and yet the gloomy draw of the superhero film is as irresistible now as it was 15 years ago. Exceeding anything its genre has produced before or after its release, The Dark Knight is a transcendent feat in American moviemaking and one of the finest films produced by the modern studio system.

Ironically, it’s also a film that stands apart for Nolan as well. To date, it’s the only movie on this list told entirely in a chronological order, and one that seems less concerned with the effects of time on an individual as it is with the weight of the future on a greater collective. Indeed, Gotham City has never more convincingly felt like a real place than in this ensemble film about how American institutions crack under pressure (particularly due to the threat of terrorism in the post-9/11 years). Gary Oldman’s copper Jim Gordon and Aaron Eckhart’s district attorney Harvey Dent are as much protagonists as Bale’s tortured vigilante. And how they all react to the existential threat of Heath Ledger’s Joker is exhilarating on each viewing.

Ledger deserved his posthumous Oscar as chaos and nihilism made flesh. He turned a comic book character into one of the greatest portraits of ill-intent in cinema, but everything about this film is firing on all cylinders, from Nolan and cinematographer Wally Pfister pioneering IMAX photography in narrative filmmaking to Michael Caine’s perfectly measured monologue about the nature of evil and societal collapse. This is a movie decidedly of its moment, yet also an achievement that will stand for all time.