Best Classic Movies on HBO Max

We dive into the delightfully dense collection of classic Hollywood movies on the new HBO Max streaming service.

HBO Max is here, and for those who are eager to revisit Friends for the umpteenth time or wait patiently for “the Snyder Cut” of Justice League to actually be willed into existence, that’s good news. Yet for movie fans of a certain type, the most exciting thing about the new streaming service is its access to what is arguably the richest collection of Hollywood classics in the world.

Not since the unnecessary demise FilmStruck has there been a streaming service with this level of classic cinema density. With access to the Warner Bros. vault of Golden Age Hollywood, as well as all the pre-1986 MGM film rights Ted Turner bought from what was once the biggest studio on the block, there is a depth of variety at HBO Max’s disposal. Also partnering with the Criterion Collection, HBO Max is a film lover’s haven.

For the sake of clarity this list will be focused primarily on Hollywood classics produced either during the proverbial Golden Age (between the 1920s and 1960s) or the beginning of New Hollywood during the 1970s, which at this point is also looking like a lost golden age all its own. So sit back as we take you through some of the many options.

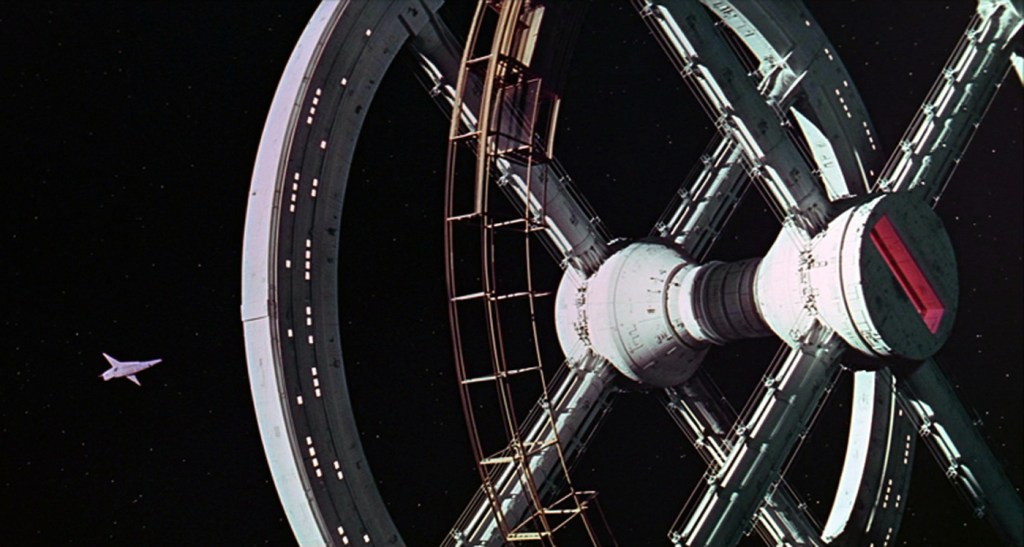

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

For his entire career, Stanley Kubrick said he wanted to change the way people made movies, and he accomplished that with the staggering achievement of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Telling an interstellar epic that begins with the birth of man and ends with an enigmatic type of first contact beyond a star gate on one of the moons of Jupiter, 2001 is a psychedelic fantasia of imagery that still haunts its entire medium. With a vision that alternates between spellbinding grandeur as space stations sway to “The Blue Danube” waltz and the primal dread of technological obsolescence—personified by the disembodied voice of computer HAL 9000—this is one for the ages.

42nd Street (1932)

An important film in the history of the movie musical—if not necessarily the greatest example of one—42nd Street is credited with inventing the “backstage musical” and the many tropes that would soon become clichés over the next 30 years. This one has it all: a down on his luck musical director who is risking his own health to make sure a star is born; a last minute casting reversal on opening night; and the naïve ingénue who’s “going out a youngster but is coming back a star.” Yes, that line’s in it too. Really it’s worth watching for the titular “42nd Street” musical number, even if the genre was still some years away from Fred and Ginger actually having star-making moves while dancing cheek-to-cheek.

Adam’s Rib (1949)

Arguably the greatest of Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn’s collaborations, Adam’s Rib is the George Cukor directed romantic comedy that showed a couple of married lawyers go to war in the courtroom. Not quite a screwball comedy, the picture has a tangible edge with its vision of deceptive marital bliss getting upturned because Spence’s Adam is thunderstruck his wife Amanda (Hepburn) would want to take up the case of Doris Attinger (Judy Holliday). Doris is a woman accused of attempted murder after shooting her husband in the shoulder upon discovering he was having an affair. But maybe Adam’s just miffed since he’s prosecuting Doris and will now have to face his wife with a judge between them? Yeah, the setup still has bite 70 years later.

Apocalypse Now (1979)

Definitely a New Hollywood movie, Apocalypse Now is the fever dream suffered by Francis Ford Coppola after years in the Filipino jungles while slowly losing his mind. He went there to shoot a Vietnam War movie loosely based on Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness—an idea hatched by John Milius and George Lucas nearly 10 years earlier when the Vietnam War was still going on, which is where they wanted to film!—but he came back with something more esoteric and slippery than that. With breathtaking imagery of American Hueys descending upon North Vietnamese villages to Wagner and Martin Sheen ascending from primordial ooze like Lazarus after a heart attack (true story: Martin Sheen had a heart attack while filming), this is the stuff of beautiful nightmares.

A Streetcar Named Desire (1951)

Elia Kazan’s film adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ Pulitzer Prize-winning play remains a painfully raw parable about the danger of relying on the kindness of strangers. It also stands as a fascinating crossroads in Hollywood moviemaking since Marlon Brando plays the brutish Stanley Kowalski and Vivien Leigh is Blanche Dubois, an aging Southern Belle who’s on her last rope when she moves in with her sister/Stanley’s wife Stella (Kim Hunter). Thus the film stars the face of a new generation of method acting in Brando and the icon whose visage adorned the posters of the biggest Hollywood hit of all-time, Gone with the Wind. Her old school mannered performance contrasts brilliantly against Brando’s more instinctual lashings, just as Blanche finds herself lost and slowly dying in a world she no longer understands.

Ben-Hur (1959)

Director William Wyler liked to crack that “it took a Jew to make a good movie about Christ,” but even then he’s being modest. His adaptation of Lee Wallace’s 1880 novel, and remake of a 1925 silent film of the same name, remains the best movie ever made about the life and times of Jesus—though we never see the messiah’s face or hear him speak a word. Rather that’s background noise to the epic saga of Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston doing his best to personify a marble statue), a Jewish prince wrongfully accused by his Roman childhood friend and condemned to slavery. He fights his way out of bondage and rises the heights of Roman power and acclaim, particularly when he leads a chariot race in one of the greatest action sequences ever filmed in spectacular 70mm. Oh yeah, and he gets saved or something by a guy on the cross at the end.

Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

One of the movies that is ironically credited with bringing down the stuffy old way of making movies during the “Golden Age,” Bonnie & Clyde now stands as one of the industry’s greatest achievements in the 1960s. With a grounded verisimilitude that seemed revolutionary in ’67, the film follows a highly romanticized depiction of real-life bank robbers Bonnie and Clyde by turning them into youthful anti-establishment folk heroes perfect for the Vietnam generation. For better and worse, it cemented Warren Beatty’s star power while making a star out of Faye Dunaway. It also was the most violent American movie ever made when it was released, and Bonnie and Clyde’s deaths still pack a visceral wallop now every time another bullet hole is made in its heroes’ bodies.

Bringing Up Baby (1938)

The ultimate screwball comedy, Bringing Up Baby asks what do you get when you combine Cary Grant, Katharine Hepburn, and a leopard named Baby? Cinematic bliss. With Howard Hawks’ legendary ear for Tommy gun fast ratatattat dialogue and a winsomely light premise about a bookish paleontologist and flighty debutante running around Connecticut searching for a dinosaur fossil the dog buried, this is nothing short of perfection.

Casablanca (1942)

If you are only ever going to see one movie made before 1950, this should probably be it. A masterpiece of the Hollywood system firing on all cylinders, everything is preternaturally perfect about Casablanca. Michael Curtiz’s direction is at its best as it lands every single zinger and witty wordplay in the Epstein Brothers’ screenplay; Claude Rains is at his most sardonic as the morally flexible French Capt. Louis Renault; Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman sizzle as the star-crossed lovers who will always have Paris but nothing else after her supposedly dead husband returns from a Nazi concentration camp; and the patriotism of both American and French nationalities besieged by the threat of Nazism during the height of World War II soars.

Sure, Dooley Wilson’s wistful version of “As Time Goes By” became a standard for a reason, but it’s the scene where actual French actors sing “La Marseillaise” while their characters are under German occupation that’ll make you want to stand up and applaud.

Citizen Kane (1941)

AFI called Citizen Kane the greatest movie ever made. While I might stop short of that much praise, it definitely is one of the most important and innovative pictures ever produced. Shattering the standard way studio movies were mass produced, writer-director-actor Orson Welles (and cinematographer Gregg Toland, who Welles gave equal billing) reinvented how movies could be made and how a director might leave an authorial stamp. With its deep-focused cinematography and high-contrasted shadow lighting, Citizen Kane conjugated a new visual vernacular in its thinly veiled satire/takedown of William Randolph Hearst and yellow journalism. It’s an American tale of corruption and the death of best laid plans. One can relate today.

City Lights (1931)

Arguably Charlie Chaplin’s best comedy, City Lights is certainly an audacious achievement considering it came out in ’31. Despite the entire industry going crazy for talkies years after The Jazz Singer, Chaplin insisted on retaining his vision of one more silent film for his on screen alter-ego, the Tramp. However, he did use innovations in sound to personally write the musical score to his movie for the first time. The result is a lyrical romance about the Tramp falling in love with a blind flower girl (Virginia Cherrill) in the big city. With poetic vignettes of skating and daydreaming, the film is reputedly the favorite comedy of Orson Welles, Stanley Kubrick, and Woody Allen.

Cool Hand Luke (1967)

What we have here is failure to communicate. That’s what Strother Martin’s Captain liked to opine whenever Paul Newman’s Luke, a convict on a chain gang, displayed insubordination. Suffice to say that failure bedeviled the two to the bitter end of this provocative ’67 prison drama that subverts the American cliché of the solitary rebel by taking it to its most pathetic, and inevitable, extreme. Along the way though, it’s fun to see all those hardboiled eggs get eaten.

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

Stanley Kubrick’s Cold War satire may still be the most subversive comedy to come out of the Hollywood studio system. Loosely based on the deadly serious Peter George novel Red Alert, Dr. Strangelove takes the piss out of Pentagon pretensions and think tank rationalizations for nuclear war just two years after the Cuban Missile Crisis. Shot in stark black and white, all the better to resemble the somber Oscar bait dramas of its day, Kubrick presents his farce with a straight face all the way until Peter Sellers (in one of three roles) rolls into the president’s war room as a Sieg Heil-ing Nazi scientist who is going to drag the American government into caves for the next 50 years while bombs fall over Moscow. It turns cynicism into an art-form and mushroom clouds into a lover’s embrace.

Freaks (1932)

Tod Browning’s horror classic may not be politically correct by modern standards, but it’ll make your blood run cold all the same. The film is about a beautiful trapeze artist (Leila Hyams) who marries her circus’ sideshow leader (Wallace Ford) for the inheritance. At first she is embraced by the deformed and disabled “freaks” of the sideshow. But after they learn the calculating truth, they come for her chanting, “One of us.” The ending will still make the hairs on your skin stand up.

Gone with the Wind (1939)

David O. Selznick’s sweeping technicolor adaptation of the Margaret Mitchell novel will forever keep its status as the most popular movie ever produced. Seriously, when adjusted for inflation it sold more tickets than Avengers: Endgame and The Rise of Skywalker combined. However, it’s also incredibly dated with its dishonest depiction of the Antebellum South and “Lost Cause” mythology that pretends slavery wasn’t so bad, and that the South seceded for noble reasons and not to keep black Americans in horrific bondage.

It is totally understandable if this movie is unwatchable for you on those grounds, but as a piece of cinematic art it is still an engrossing fable told with the pinnacle of 1930s Hollywood production. Vivien Leigh is a legend for her atypical performance of a deeply flawed anti-heroine who survives the Civil War and Reconstruction through any means necessary, and the way Max Steiner’s elegiac score swells around her as Atlanta falls and she must wade through thousands of dead and dying extras is still a testament to the power of cinema—as is Union General William Tecumseh Sherman’s biblical wrath as that city is then consumed in flames.

Harold and Maude (1971)

The most unconventional of love stories, Harold and Maude is Hal Ashby’s cheeky romantic comedy about a young man (Bud Cort) falling in love with a much older woman (Ruth Gordon). Definitely a movie that embraced the counterculture of its age, Harold and Maude has also aged very well as a sweetly eccentric romance that tries to provoke with its 91 minutes of deadpan delivery.

King Kong (1933)

Still the best “giant monster” movie ever made, Merian C. Cooper’s big ape film tapped into something mythic (and problematically primal) in its vision of a gorilla out of 19th century colonialist adventure yarns climbing the literal pinnacle of early 20th century ingenuity when Kong ascended the Empire State Building. More than just the definitive adventure movie of the Depression, it inspired everything that came afterward from Godzilla to Jurassic Park. It also still stands tall among its descendants with a “beauty and the beast” pseudo-romance between Kong and Fay Wray’s infamous screeching lungs. Racial connotations notwithstanding, King Kong really is the Eighth Wonder of the World.

Lilies of the Field (1963)

The movie that won Sidney Poitier the Oscar for Best Actor—a first for a man of color—Lilies of the Field is a parable about a man named Homer being persuaded by some surprisingly dishonest German nuns to build them a chapel in Arizona. Poitier grows from unpaid handyman to seeming gift from God—the title is quoted from the New Testament’s Sermon on the Mount—but it’s really his performance that brings dimensionality to what is otherwise a well-meaning archetype created by white men. A progressive film for the Kennedy years, it is Poitier who maintains its poignancy today.

Network (1976)

Director Sidney Lumet and screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky’s eerily prophetic satire of the corporatization and corruption of media is as potent as ever. This post-Watergate movie predicted the menace of Fox News, infotainment, and reality television decades before their inception. And a testament to its legacy is that the “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore!” catchphrase is uttered by Howard Beale (Peter Finch), a news anchor who’s had a mental breakdown and has become raving mad. His rant, however, appeals to disenfranchised 1970s Americans and is then defanged by his network into an empty bumper sticker slogan—just as how it’s used by talking head opinion leaders to this day.

… and that’s just the first act of a movie that culminates in Beale becoming a televangelist (before that was a thing) where he preaches the word of his corporate overlords until the day his ratings slip and he’s subsequently executed on live TV for a bump in the ratings.

North by Northwest (1959)

Alfred Hitchcock’s exciting spy caper was a trailblazer in its day, likely helping inspire the tone of the James Bond movies that began a few years later as much as Ian Fleming’s novels. With its familiar plot about mistaken identities and espionage femme fatales, North by Northwest is powered by the frantic pace of its cross-country chase sequences in which a milquetoast Cary Grant must rise to the occasion of becoming an international man of mystery if he hopes to save the girl from a snooty James Mason while jumping across the rock faces of Mount Rushmore!

Paths of Glory (1957)

Before there was 1917, there was Paths of Glory. Stanley Kubrick’s revolutionary movie about the First World War is still a stunning achievement with its long tracking shots throughout the trench network of the Western Front and the circuitous hell of those trapped there. His camera follows Kirk Douglas as Col. Dax, a commanding officer who must defend his men who’ve been accused of an act of cowardice because they ignored orders to attack an enemy position in what surely would have been a suicide mission. An anti-war film before that was a common thing in Hollywood, Paths of Glory remains one of the most visceral pictures about the Great War that was supposed to end all wars.

Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

The second of James Dean’s only three films, Rebel Without a Cause is probably his most famous picture. Focused on the raucous nature of “youth” during the first decade the WWII generation had to deal with their kids growing up, Rebel Without a Cause is a Nicholas Ray movie with a reputation that I’d argue is a little greater than its actual merit. Featuring some terrific, groundbreaking performances from Dean and Natalie Wood (who had an affair with Ray on the film despite being underage), the movie attempted to find a voice for the inarticulate misery of coming of age and being asked to conform. However, this motif was done better in films that didn’t necessarily see themselves as important with a capital “I” later on.

Singin’ in the Rain (1952)

What I would argue is the finest movie musical ever made, Singin’ in the Rain is like dancing in starlight. The result of perfect harmony between MGM’s famed Arthur Freed unit for movie musicals, Gene Kelly’s relentless dancing-turned-athleticism, and director Stanley Donen’s breezy framing, this is as charming as Hollywood fantasies get. The gist is that it’s a movie about the advent of sound in 1920s Hollywood where an older movie star (Kelly) falls for an aspiring actress (Debbie Reynolds), who just needs one breakout role.

Getting her that moment runs into hijinks, like her being forced to dub his illiterate silent era co-star (a deliciously preening Jean Hagen). But really it’s an excuse to wallow in technicolor as much as early talkies did in music, and to mine early sound Hollywood’s best songs, including the Arthur Freed co-written “Singin’ in the Rain.” Only now the song becomes an all-time standard as Kelly sings it with a cold while skipping down a waterlogged backlot.

Stagecoach (1939)

The movie that birthed one of the most important director and star partnerships in cinema history, Stagecoach is the Western that teamed John Ford with the then unknown John Wayne. Ford’s kinetic intuition for how to frame a man on a horse in Monument Valley, as well as Duke’s underappreciated vulnerability despite being “a big man,” created many mythic images, including Wayne’s larger-than-life entrance here as the Ringo Kid. But Wayne is just one part of an ensemble of disparate strangers, some who fought for the Union and others the Confederacy, trapped together for a fateful stagecoach ride through Apache country. Did you like Firefly? That was Stagecoach in space.

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

Over 80 years later and still the best Robin Hood movie, The Adventures of Robin Hood is the definitive swashbuckler. By reteaming director Michael Curtiz with his Captain Blood stars Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland, Warner Bros. captured lightning in a bottle with this technicolor event. Cementing the image of Flynn as the Prince of Thieves, and the Prince of Thieves wearing green tights as he swings through Sherwood’s trees, this Robin Hood hits all the grace notes from the most popular legends while being a joy to watch doing so. Plus, the use of shadow silhouettes for the final sword fight? Brilliant.

The Great Dictator (1940)

My personal favorite Charlie Chaplin movie, The Great Dictator is a film the writer-director-producer-star later regretted due to learning the sheer scale of the Holocaust. Be that as it may, his willingness to mock Hitler and fascism at a time when many Americans wanted to keep out of World War II (and most studios didn’t want to upset anyone) makes The Great Dictator an act of courage. Additionally, it’s truly funny when Chaplin’s Hynkel, the fictional dictator of a land named Tomania, lovingly waltzes with a balloon shaped like the world he wants to conquer. And then it can be profoundly moving, especially these days, when Chaplin’s other role as a Jewish barber gets mistaken for Hynkel and uses a sudden global platform to speak to the camera—a rarity for Chaplin—and denounce “unnatural men, machine men with machine minds and machine hearts.”

The Maltese Falcon (1941)

Arguably the first movie in the film noir movement, and the picture that made Humphrey Bogart a star and John Huston an A-list director, The Maltese Falcon is a definitive potboiler about gin-soaked detective offices and deadly liaisons. It stars Bogie as Sam Spade, a San Francisco gumshoe who becomes suspect number one after his unloved partner winds up dead in a back alley. Not that it phases Sam in the least, nor do the come hither eyes of Mary Astor’s Ms. O’Shaughnessy or the blatant sketchiness of Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet’s characters waiting in the wings. This film enjoys one of the all-time great movie endings and will forever be the stuff dreams are made of.

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956)

Another of Alfred Hitchcock’s star-studded ‘50s effort centered on mistaken identity, this one sees family man Benjamin (Jimmy Stewart) thrown into the deep end of espionage backstabbing after an acquaintance reveals himself to be a spy, whispering life-or-death information in Ben’s arms with his dying breath. That information leads to the son of Benjamin and wife Josephine (Doris Day) getting kidnapped and the pair being blackmailed into a plot that culminates with the most exciting night at the symphony you’re ever likely to experience. Again one of Hitch’s lighter efforts, but even when he is being light it’s still suspenseful as hell.

The Philadelphia Story (1940)

Another of the all-time great screwball comedies, George Cukor’s The Philadelphia Story reteamed Cary Grant with Katharine Hepburn to sublime effect. Set in the rarified airs of east coast blue bloods—so a real stretch for Hepburn—the film opens with Grant’s Dexter and Hepburn’s Tracy Lord divorced but still in each other’s lives in that slightly incestuous way one sees at country clubs across the eastern seaboard. Not that the rest of her family minds: they love Dex way more than the man she’s about to marry in social climbing George Kittredge (John Howard). That wedding will be the event of the season, however, and even attracts hard nosed reporter Mike Connor (Jimmy Stewart) to the family estate for the weekend. Hijinks, high amounts of alcohol, and highly eyebrow-raising incidents ensue.

The Searchers (1956)

As John Ford’s best movie, The Searchers was his first serious attempt to reckon with the anti-American Indian bigotry of his earlier films. It’s likewise a sweeping epic of revenge and cultural identity that resonates today. Also the best showcase of John Wayne’s talent, the film stars the Duke as Ethan Edwards, a nasty racist sonofabitch who just got home from fighting for the Confederacy only to see his brother’s Texan family massacred by Comanche Indians. Well, all except his brother’s little girl, Debbie.

So it is that Ethan and half-Cherokee Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), who was an adopted son to the family, go on a Homeric quest to save Debbie. But as the years pass, and adult Debbie (Natalie Wood) grows into a young woman married to one of her Indian captors, what becomes a mission of vengeance turns into something darker as Ethan plans to murder his “ruined” niece and Martin perseveres to save her from Ethan. All the way through, Ford achieves the most ruthlessly beautiful photography of Monument Valley ever committed to film.

The Treasure of Sierra Madre (1948)

The film featuring Humphrey Bogart’s best performance, The Treasure of Sierra Madre inspired Indiana Jones, only this version of Indy is a mean old bastard. His name is Frank C. Dobbs, and he’s a washed up drunk in Mexico when he lights on the idea of there being gold in them there hills among the Sierra Madre Mountains. So he and another American adventurer enlist Walter Huston’s old-timey prospector to take them in the hills to mine for gold. The problems only occur when they find it, and Dobbs in particular starts sizing up the others’ worth—and if they can make it back to town safely. It’s writer-director John Huston’s personal favorite too.

The Wizard of Oz (1939)

Another classic out of the height of MGM’s heyday, The Wizard of Oz is the masterpiece that transformed L. Frank Baum’s turn of the 20th century specific American fantasy novel into an ageless dream for all future generations. With gorgeous technicolor, ear-worming songs, and a star-making turn by teenage Judy Garland, this is a movie every era of parents continue to pass to their kids for a reason. That’s all the more miraculous when you consider MGM almost cut “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” because they thought the song was too sad for wee ones.

But this is just a sampling of all the classic movies on HBO Max. For that reason, below is a list of many other all-timers we left off, as well as a few foreign masterpieces from yesteryear you shouldn’t sleep on.

8 ½ (1963)

A Hard Day’s Night (1964)

An American in Paris (1951)

A Star is Born (1954)

Bicycle Thieves (1948)

Black Narcissus (1947)

Breathless (1960)

Carnival of Souls (1962)

Cheyenne Autumn (1964)

Dirty Harry (1971)

Doctor Zhivago (1965)

Foreign Correspondent (1940)

Giant (1956)

Godzilla (1954)

Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933)

Gold Diggers of 1935 (1935)

Great Expectations (1946)

Lolita (1962)

Lord of the Flies (1963)

Love in the Afternoon (1972)

Modern Times (1935)

Now, Voyager (1942)

Of Mice and Men (1939)

Oliver Twist (1948)

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

Pat and Mike (1952)

Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975)

Pygmalion (1938)

Rashomon (1950)

Rome, Open City (1946)

Seven Samurai (1956)

The 47 Ronin (1941)

The Seventh Seal (1958)

That Hamilton Woman (1941)

The 39 Steps (1935)

The 400 Blows (1959)

The Blob (1958)

The Hidden Fortress (1959)

The Lady Vanishes (1938)

The Most Dangerous Game (1932)

The Naked City (1948)

The Nun’s Story (1959)

The Red Shoes (1948)

The Thief of Bagdad (1940)

The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962)

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964)

The Wild Bunch (1969)

To Be or Not to Be (1942)

Tom Jones (1963)

Woman of the Year (1942)

Yojimbo (1961)