How 2001: A Space Odyssey May Have Predicted a Surprising Aspect of Space Travel

A study on how space travel may affect our brains shows how 2001: A Space Odyssey may have predicted a few things about the consequences of space flight.

Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is regarded today as one of the most influential and important pieces of science fiction ever made. Decades later, the story of how man was born and reached the stars still feels like more than just a space-faring fairy tale. Today, the movie is recognized for its predictive power. In fact, according to a new scientific study, 2001 may have predicted yet another aspect of space travel researchers are only beginning to understand.

The Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) released a study in April 2020 that shows how the human brain could be affected by prolonged exposure to microgravity in a spacecraft. This isn’t the first time that doctors and scientists have encountered changes to human physiology in astronauts, including cases of muscle atrophy and the deterioration of a subject’s skeleton. As Space.com notes in its own report on the study, there have also been many recorded cases of astronauts suffering from issues with their eyesight after returning from space.

“Medical evaluations on Earth have revealed that astronauts’ optic nerves swell and some experience retinal hemorrhage and other structural changes to their eyes,” Space.com‘s Chelsea Gohd writes. “Scientists suspect that these vision issues are caused by increased ‘intracranial pressure,’ or pressure in the head, during spaceflight.”

Now, the new study by the RSNA, led by Dr. Larry Kramer, a radiologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, has found that intracranial pressure may also cause changes in the brain. After running MRIs on 11 astronauts before and after space travel, Kramer and his team found that prolonged exposure to microgravity and the resulting intracranial pressure could cause the brain to swell as well as change the volume of cerebrospinal fluid and the shape of the pituitary gland. Furthermore, Kramer found that these changes could persist a year after the subject had returned from space and may even be long-lasting issues, although the radiologist admitted that more study was needed.

Kramer theorizes that a lack of gravity in space causes blood to rush to the head instead of circulating throughout the body.

“The blood that normally pools in the extremities redistributes toward the head,” Kramer told Space.com. “It’s not something that we normally experience on Earth unless you’re sort of standing on your hands.”

If shorter stints in space have this effect on humans, what could this mean for the men and women who dream of setting foot on Mars or traveling beyond our solar system? Kramer said that there are “countermeasures” being tested to remedy microgravity’s effect on the body, including “spinning an astronaut around for a certain portion of the day, just moving the blood through the body and back towards the legs.” The radiologist noted that this method calls to mind images from 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Much has been written about Clarke and Kubrick’s attempt to make “the proverbial good science fiction movie” that would not only entertain but was also scientifically accurate and could explain space travel to the viewer. While Star Trek‘s Starship Enterprise had spent the ’60s zooming through space at warp speed and firing photon torpedoes, Clarke and Kubrick were interested in telling a story that not only respected the laws of physics but felt realistic. At a time when science fiction was still largely viewed as B-movie fare, Kubrick wanted to make a deeper science fiction movie.

“He wanted to make a movie about Man’s relation to the universe–something which had never been attempted, still less achieved, in the history of motion pictures,” Clarke wrote about Kubrick in his making-of memoir The Lost Worlds of 2001.

There’s an abundance of great and respectable science fiction movies in 2020, but when Kubrick first approached Clarke about developing a movie together in 1964, “serious” science fiction of the 2001 variety was still a noble concept.

“Of course, there had been innumerable ‘space’ movies, most of them trash,” Clarke wrote. “Even the few that had been made with some skill and accuracy had been rather simpleminded, concerned more with the schoolboy excitement of space flight than its profound implications to society, philosophy, and religion.”

Kubrick “was fully aware of this,” according to Clarke, “and he was determined to create a work of art which would arouse the emotions of wonder, awe…even, if appropriate, terror.”

As far as terror goes, many images from 2001: A Space Odyssey come to mind: astronaut Frank Poole helplessly floating into the empty vacuum of space, the incomprehensible shriek of the Moon Monolith, HAL’s emotionless red eye staring at the camera, and David Bowman’s tumble through the psychedelic “Star Gate.” But there’s one specific aspect of the movie that may frighten viewers who prefer to keep both feet on the ground at all times: the disorienting way in which the men and women of 2001 traverse the movie’s spaceships.

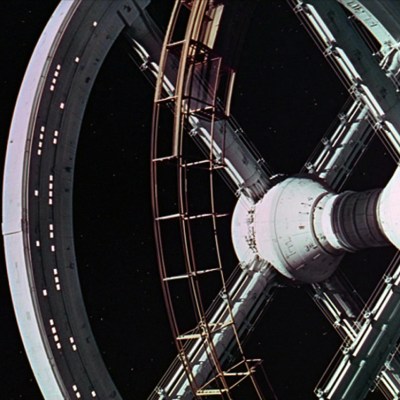

We first experience the rotating sets of 2001 as Dr. Heywood Floyd approaches a spinning space station on his way to Clavius Base on the moon. The flight attendants use special shoes to walk around the ship despite the lack of gravity. At one point, we watch as a stewardess slowly walks up a circular wall until she’s upside down, the only way she can access a door to a different part of the ship. It’s a beautiful, tediously slow scene, accompanied by Johann Strauss’ “The Blue Danube Waltz,” that introduces Kubrick and Clarke’s vision of space travel in dizzying fashion.

Later in the movie, the camera follows Frank Poole as he jogs around a revolving, carousel-like centrifuge inside the Discovery One that’s designed to simulate the gravity of Earth. This scene is our best look into how Kubrick and Clarke envisioned artificial gravity through the use of centrifugal force (the constant spinning of the chamber) playing a key role in interplanetary space travel. Even if they couldn’t predict the specific effects on the brain space flight could have on astronauts, they seem to have understood that simulating Earth’s gravity would be pivotal to surviving longer missions in space.

Surprisingly, while the Discovery One went through many design iterations before the production team landed on the look of the ship, Clarke wrote in The Lost Worlds of 2001 that “the final decision was made on the basis of aesthetics rather than technology.” But Kubrick’s true goal was scientific accuracy — and he did his research.

The director consulted with experts such as NASA scientist Fred Ordway, who worked as the movie’s technical advisor, and Harry Lange, an artist who’d worked at NASA illustrating concept models of potential spacecraft and space stations for the agency’s Future Projects section. Lange drew the designs for the ships of 2001 based on what he’d seen during his NASA years.

“I’d seen real hardware at Cape Canaveral and in NASA’s research laboratories and hangers, so I knew what the equipment had to look like. The surface of the Discovery model had to look as if it could withstand asteroid dust, and virtually every button on every console had to be depressible.” Lange told BBC News in 2002. “These had to be designed as if they could travel to the edge of the solar system and beyond.”

Years later, Lange worked on the first three Star Wars movies, both in the art and production design departments.

Kubrick hired production designer Anthony Masters to bring Lange’s designs to life, but he also outsourced sets, props, and costumes to real aerospace and engineering firms, including Vickers-Armstrong Engineering Group, which was tasked with building a working version of Discovery One‘s centrifuge on a soundstage at MGM-British Studios in Borehamwood, England. The 30-ton Ferris wheel-like set was 38 feet in diameter, 10 feet wide, and could rotate at up to three miles per hour. It cost $750,000 to build. To film the famous jogging scene, actor Gary Lockwood jogged in place while the set rotated, the cameraman shooting from above while Kubrick directed from a control room using a video feed.

The rest of the Discovery One went through the same painstaking process of research and design, from the kind of engine that would power the ship — they decided on the fictitious “Orion nuclear plasma drive,” which was based on a real concept from the ’50s — to whether the ship should have “cooling fins.” Kubrick nixed Clarke’s cooling fins because he thought they looked too much like wings. The director knew that aerodynamics didn’t matter in space.

“We wanted Discovery to look strange but plausible, futuristic but not fantastic,” Clarke wrote in The Lost Worlds of 2001.

Ordway also wrote of the extent to which the production team familiarized itself with each aspect of the ship: “We insisted on knowing the purpose and functioning of each assembly and component, down to the logical labeling of individual buttons and the presentation on screens of plausible operating, diagnostic, and other data.”

This attention to detail paid off. Not only was the 1968 movie unlike anything audiences had ever seen on screen before — they were still a year away from watching Neil Armstrong walk on the moon — but it did the thing that good science fiction often does: predict a vision of our future. Not only did 2001: A Space Odyssey accurately depict several aspects of space travel as we understand it today — the lack of sound in space, the weightlessness of a low-gravity environment, and the delay in communications from spacecraft a long way from Earth — but also predicted things like video conferencing from long distances, the proliferation of computers in our daily lives, the moon landing, the International Space Station, glass cockpits, and more.

But for all it got right, it was also wrong about a few things. As NASA pointed out in its “Ask an Astrophysicist” column, one of the movie’s most exciting scenes would have had a very different outcome in real life. Right before Dave Bowman jumps out of his space pod without a helmet, braving the harsh conditions of space in order to return to the Discovery One, he takes a deep breath.

“If you don’t try to hold your breath, exposure to space for half a minute or so is unlikely to produce permanent injury. Holding your breath is likely to damage your lungs” NASA explains.

The accuracy of certain aspects of the centrifuge chamber has also been called into question. As a Wired piece on how artificial gravity works inside 2001‘s iconic spaceship explains, this spinning centrifuge’s function should actually be to counteract the weightlessness astronauts feel in space.

“Really, a spinning spacecraft could produce an artificial apparent weight – but not artificial gravity,” professor of physics and Wired columnist Rhett Allain wrote in 2013. “Astronauts in orbit feel weightless because there isn’t a contact force pushing on them but there is a gravitational force. What you feel while standing on the Earth is actually the force of the ground pushing on you and not the gravitational force. In order to feel weight, you don’t even need a gravitational force. All you need is a force from the floor (or something) pushing on you.”

Another issue is how Bowman and Poole are able to so easily switch between the artificial gravity of the centrifuge and the microgravity of the rest of the ship, a feat that some scientists say would be much more difficult to achieve due to the motion sickness and balance problems it would cause.

Yet, as an approximation of our scientific reality, 2001: A Space Odyssey is still an absolute marvel and arguably the greatest achievement of the creative duo who dared to imagine what “the proverbial good science fiction” would look like in 1964. And as the RSNA study proves, we can still learn quite a bit from Kubrick and Clarke’s big-screen science experiment.