The Zombies’ Rod Argent Breaks Down Their New Album Different Game

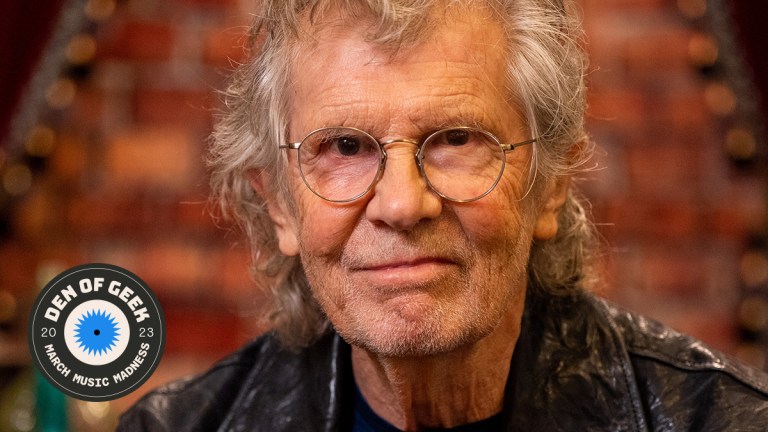

Exclusive: Rod Argent breaks down the new album and remembers Ringo Starr as The Zombies rise again with their new album Different Game.

The Zombies only released two albums during their initial run, but the hits keep them coming back. Director Robert Schwartzman’s documentary, Hung Up on a Dream, named after a song from their classic album Odessey and Oracle, premiered at the Zach Theater during SXSW on March 12. Cooking Vinyl Records will release Different Game on March 31.

The Zombies’ first full-length album since 2015’s Billboard-charting Still Got That Hunger features founding keyboardist Rod Argent and lead singer Colin Blunstone, along with drummer Steve Rodford, guitarist Tom Toomey, and bassist Søren Koch. It retains the variety of sounds the band has been cultivating since their formation in 1961.

In 1964, The Zombies won a recording contract with Decca Records, the same label as the Rolling Stones, as first prize in a contest sponsored by The London Evening Post. Their single, “She’s Not There,” hit the charts internationally, and the band was part of the first wave of the British Invasion. Their first album, Begin Here (1965) merged jazzy licks, minor chords, and syncopated rhythms into pop structures.

The Zombies’ Odessey and Oracle was recorded at EMI’s Abbey Road Studios with engineers Geoff Emerick and Peter Vance. The Beatles had only just finished recording Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band at the studio, and Pink Floyd recently finished up The Piper at the Gates of Dawn there. The Zombies split after playing their final gig in mid-December 1967. They never got to perform the cult masterpiece with their defining hit, “Time of the Season,” live with the classic lineup: Argent, Blunstone, Chris White, Paul Atkinson, and Hugh Grundy

Argent continued to write with White for the band Argent, which the keyboardist launched in 1972. Their first single, “Hold Your Head Up,” was a radio smash, and their songs provided hits for Three Dog Night and KISS. Argent played the piano on the title song of The Who’s Who Are You. He was part of the 2006 line-up of Ringo Starr’s All-Starr Band, and regularly joins the music cruise with the Moody Blues’ Justin Hayward. Argent spoke with Den of Geek about keeping The Zombies fresh.

Den of Geek: You’ve been working with these musicians since you were very young. Do they still surprise you?

Rod Argent: Colin surprises me. His voice has obviously changed a little because he’s now 77, as I am, but in many ways, it’s got stronger because he works at it. He doesn’t just let it go. He really practices, and does exercises. When we’re on the road, he does three exercises a day before we even play. And you can see the results of that. It’s like a muscle, and he really keeps it as good as he can get it.

The makeup of the band now, it’s only Colin and me that are from the original Zombies, but the other guys have been with us for a long time. Apart from the bass player [Søren Koch], who came on board when Jim Rodford sadly passed away. But they always surprise me, constantly, because everyone seems to just get better.

Different Games explores a wide range of styles. The title track starts out almost readily familiar with that beautiful Hammond and the time change part is perfect.

It came after my wife and I went to the Bach Festival and heard a live performance of the “Mass in B minor.” During “Sanctus,” there was a chord sequence that really blew my mind. I just loved it. It sounded, because in the church there were two organs, two choirs, some orchestral instruments as well, so loud. It was a packed church, and it was like being at a rock concert. It was really fantastic. When I got back, I couldn’t stop playing. I was just messing around with the chords, and one part of it I adapted. So, if it sounds a bit familiar, it’s because it comes from a Bach thing.

Are you an inspirational writer or do you sit down and say it’s time to write a song?

A little of both really. The trigger could be anything. It can be just hearing a groove and thinking, “Oh, I’d love to write something in that sort of groove,” and then just messing around on the piano.

I often start with nonsense words. But those nonsense words always eventually start to click into something that has a personal meaning to me. You hope you make something that’s universal enough for people to bring their own interpretations to it, and I’m a great fan of that idea. But it can start from a chord sequence.

On “Dropped, Reeling and Stupid,” I just was messing around on the piano without thinking of writing a song. I hit this opening chord sequence which I really liked, and I went to the studio. I had an idea in my mind of an inspiration for the lyrics of that one, actually, but I’m not going to tell what it is because I want people to bring their own.

“Rediscover” sounds like a timeless Torch Song. What songwriters gave you that feeling and how did that feel coming out?

I don’t know where the body of the song came from, from an inspiration point of view. But the very opening eight bars, where there’s almost nothing going on except harmonies. We were actually on a co-headline tour with the Beach Boys, with Brian Wilson and Al Jardine and everybody. I had a day off, and listening to the Beach Boys was just in my head, but it’s not a copy or anything. I just fancied something a little bit dissonant, with some harmonies that just clashed a little bit.

I think the melody is strong. But there were some very jazzy chords and I loved using those. I started messing around with a chord sequence and I thought I’m gonna get the guys to sing it in soundcheck. It was just eight bars.

Did you write out the arrangements for the time signatures on “Dropped, Reeling and Stupid?”

I wanted to write a section like that but it absolutely came into my head vocally. I know it’s instrumental, but I thought it’d be great for us all to play that riff, and end on a really high note, which sounds exciting, and then the zoom back into the song. I also wanted that song to be Colin and me swapping vocals.

Did you score the strings on “I Want to Fly?”

I didn’t. That’s the one string arrangement I didn’t do. I’d already scored a version of that on a previous album ages ago, but it was done with the whole band. I said, we should really revisit this, and I won’t let Chris Gunning, the arranger, hear anything of the original track. He really wanted to and I said no. I just adore the way it turned out.

Chris White, the original bass player in his Zombies, and I produced an album for Colin called One Year. Gunning, a classical composer who also wrote music for film and television, did the strings, scoring on that album. I loved his work, absolutely loved it. “I Want to Fly” is an affectionate look back at Colin’s One Year album. I think it sounds just as good as anything on it. So, I’m over the moon with that.

The other string arrangements on Different Game and also on You Can Be My Love, they were mine.

Do you write them in notation?

Yeah, it was notation, absolutely.

Do you see ad hoc music theory, the stuff you know inherently, as an extra instrument?

Yeah, I do. I’ve always loved classical music, for instance. It never stopped me listening to Elvis singing “Hound Dog,” which really turned my world around and turned me on to rock and roll. And it never stopped me listening to anything else. The early Miles Davis band, which I just loved, and Milestones, which was the first thing that I heard from him.

I remember coming off the road after Argent and thinking: I knew how to sight read, but it was very primitive. I’m going to spend a year just putting any music, no matter how easy or how difficult, in front of me, and try to play in time. No matter how slowly. It was just like learning to read it or learning a language. I did that for three hours a day. By the end of the year, I was pretty good with notation.

Then, when you could get samples on synthesizers, etc., I could try out in a rough form what I was writing. Which is how I did the end of “Different Game,” the orchestral bit where it breaks down. I improvised that on a keyboard with some string samples, and then scored it. It was instinctive and just once through. I don’t know how I wrote it, I couldn’t do it again, it was at the moment, in that particular song. It was lovely to be able to score it.

We use a great string quartet on it. Jessica Cox and a group called Q strings. They play for lots of people actually, but amongst them, Jeff Lynne and ELO. We recorded the strings in my house as well. So that was a real joy.

The beats in “She’s Not There” and “Time of the Season,” are unique in rock drumming. Like “Ticket to Ride,” they dislocate the set and are unified by a feel, almost like a hip hop beat. Do you remember what told you that sound would click?

Yes, I do, and it was because, like everybody else in 1962 onwards, The Beatles were cataclysmic, if you heard them, and I just loved Ringo’s drumming. Ringo quite often came up with some really jagged, sort of broken-up rhythms in verses. I loved that idea. I didn’t copy a Ringo rhythm. But the idea in my mind was to have a broken rhythm because The Beatles did it. “Ticket to Ride,” I can’t remember what year it came come out?

It was after “She’s Not There,” but before “Time of the Season.”

Well, Ringo used broken rhythms even on, I’m trying to think of one, “Not a Second Time?”

And “All I’ve Got To Do,” oh, “Anna,” he breaks up the set in “Anna.”

Oh, yeah, he used to do that, and I loved that, he didn’t just play straight through something. That’s where I got the idea of having a broken rhythm. That’s absolutely right. The beginning of “She’s Not There.” It was written around that original drum feel and bass line.

You recently did a live stream from Abbey Road, does it still have the same magic?

Yeah, it did. Because of COVID, we hadn’t played together for two years. We had no rehearsal. I thought everyone was trying a bit too hard on the first two or three songs, myself included, but after that, it settled into something which started to feel really, really good.

Working in No. 2, it’s quite an echoey studio, but that particular sound added something, a little bit of a golden natural reverb in it. When we were playing live in there, we set out with a PA because it was a small invited audience, so it was difficult for the engineers to record, but overall, I was really happy with the result.

Geoff Emerick engineered some of Odessey and Oracle, was he like to work with?

Geoff was a dream to work with, really quick. I remember when he engineered “Time of the Season,” that first tom tom and bass figure. I remember thinking immediately: “I don’t know what it is. It’s just the bass and tom-tom sound, but there’s something quite special about it.” I remember thinking that at the time. We recorded in just a few hours, the whole thing. We did add some things in the studio that we hadn’t rehearsed, but Geoff was brilliant.

A week before Geoff died, he came along to a concert of ours in Los Angeles. We were playing with Arcade Fire. I had an hour of conversation with him. As I left, he called across the room “Don’t forget, we have to work together again.” He said: “I’m not just saying that, will you promise to call me in a week’s time.” So, I said, “Yeah, okay. That would be really cool.” And then of course, a week later, he was dead. It was such a shock. He was a very shy guy. Really, really shy, but a lovely guy.

You name some great artists on the song “New York” from Still Got That Hunger. What artists floored you at the Murray the K shows?

I really liked listening to Chuck Jackson. He was a big star in New York, in a more local way. He sang “Since I Don’t Have You,” I really enjoyed that. I enjoyed everybody really. Ben E. King and the Drifters. But it was Patti LaBelle that really took to us, and used to hang out in our dressing room most nights. She would talk to us about Black church music. I remember her vividly saying “there’s one new kid on the block you’ve got to check out: her name is Aretha Franklin.” That was even before Aretha was with Atlantic and did the soul stuff. I think she was with CBS then, and they had her doing quite a lot of cabaret things. But even then, we loved it. We never heard of her.

I’m just thinking about what an emotional piano player Aretha Franklin was.

Oh, wonderful piano player, she’s wonderful. A lot of people don’t realize that she played on her own records, even “Respect,” and the Carole King song “Natural Woman.” The other person Patti told us about was Nina Simone to check out. When we got back, I bought all the Nina Simone albums I could find, and I bought the Aretha Franklin record on CBS. Very soon after that, of course, she started all the soul and gospel influence stuff. What a find that was. And Patti said, “I must take you to a Black church.” I’m so sorry that never happened. There was never the opportunity, really. That’s the treasure that I remember from the Murray the K Show, which is probably similar to what Colin told you.

I spoke with Colin about Hugh Grundy being on the motorcycle for “Leader of the Pack.”

Oh yes, and you know what? I had to walk up, I think it was on “Give Him a Great Big Kiss,” and I had to walk on stage and kiss Mary [Weiss, lead singer of The Shangri-Las] on the cheek.

Did you get to kick musical ideas around with the bands traveling on the Dick Clark Caravan tour?

Not really, no. I remember on the tour, one of the people in the backing band was Jimmy Guercio, who later became a hugely influential producer. And I remember Tommy Roe playing guitar. And I don’t know whether he did “Dizzy” on the tour for the first time or just writing it, but [I remember hearing him] rehearsing it on the tour.

My real memory of those tours was about three o’clock in the morning. We used to travel overnight on an ordinary coach, and by about three o’clock everyone would start to go to sleep. As they settled down one of the great singers of a Black group would go [sings mmm], and a soft chord built up by the other Black singers on the tour. And then someone would take the lead and sing a beautiful spiritual and the hairs used to go up on the back of my neck. It was just gorgeous. So that’s my big memory of that. And, of course, playing the shows. I remember Tom Petty saying it was his very first ever concert. And he lifted the setlist for me when Colin and I went around his place on the west coast.

You toured with the Ringo Starr All Stars, with a fun lineup, Sheila E and Edgar Winter, now you’re going on the cruise with the Moody Blues. Can you explain how it’s changed, from being on a bus tour with hit single makers to cruising with other rock stars?

I love it. I mean when we did that co-headline tour with the Brian Wilson Band, it was fantastic. I just loved to listen to those things live. I’ll give you one memory from the last cruise we did. Even though I always loved his music, and admired Gary Brooker and Procol Harum, I’ve never really spoken to him. I’ve said hello and that was about it. Because we were on the ship together, I had about an hour’s conversation with Gary and it was just lovely. And I suggested to him that he play “Salty Dog” on the deck with the band where he did his onboard set.

It just happened to be the most perfect, tropical night – still and warm – and he started singing “Salty Dog,” and he said, “I was having a chat with Rod, and he said, maybe I should do this song, so I am. I’m gonna play it.” He said “This is for Rod,” and he played it and honestly, I just melted. It was just a real real joy. And it was a real joy talking to him, particularly about the album he did with the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra. He was telling me about how he wrote the score for “Conquistador” on the plane going over to Edmonton, which I thought was extraordinary. Because, like me, he’s a self-taught guy, but I could never do that on a plane, just do that. So, it was just lovely having a chat with him.

I met Ringo for the first time. We did a press conference at the beginning of the tour. And they said it must be great to reunite your acquaintance with Rod again, because “She’s Not There,” in fact, was the first No. 1 in Cashbox after the Beatles with a self-written song. And Ringo said, “I’ve never met him before.” And they couldn’t believe it. But that was how it was in those days, because bands were worked to death, really. We were all on separate concerts all the time. So, we very often didn’t meet people.

We did meet the Moodies, actually, and went to a couple of social things with them. Because we lived in St. Albans, which was only 18 miles from London, we didn’t stay in London, like a lot of the bands who’d come down from the north of England. So, we would just go home, not just not just stay in London and then go down to the Bag of Nails Club or Cromwellian or whatever. So, it’s extraordinary, we seem to meet more people now than we ever did when we were first on the road all those years ago.

Hung Up on a Dream premiered on March 12. Cooking Vinyl Records will release Different Game on March 31.