What Hamilton Doesn’t Say About His Real History with Slavery

We dive into Alexander Hamilton’s real thoughts on slavery, and whether he personally ever owned human beings as property.

It was mid-October 1796 when Alexander Hamilton released the first in a string of scathing essays about political opponent Thomas Jefferson. By this point in early United States history, George Washington had announced his retirement, refusing to seek a third term as president, and the race of self-styled great men hoping to take his place was on… with none more loathsome to Hamilton than Jefferson, the loquacious, if remote, thinker on a hill in Virginia.

In this first of 25 essays, Hamilton wrote under the nom de plume of Phocion about the many hypocrisies of Jefferson, depicting the supposed philosopher as a moral and intellectual fraud, and something worse: a slave owner who knew slavery was evil but still took advantage, perhaps even of a sexual nature, of the Black people he kept in bondage.

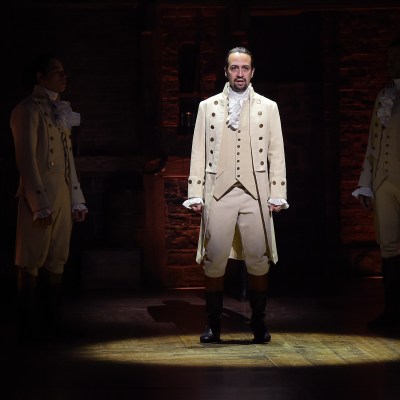

It is moments of moral standing like this, even if Hamilton hid his name under a pseudonym, that Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton hangs its hat on. While the actual incident does not technically occur in the musical’s dizzying amount of narrative events, the tour de force work of art still uses its trenchant blending of historical fact and hip hop melodies to convey much the same idea: Jefferson was a demonstrable hypocrite on the issue of slavery. Despite being one of the United States’ brightest thinkers about the rights of men, Jefferson failed time and again throughout his life to truly fight to end slavery—or free the hundreds of people he kept as possessions at Monticello. Even on his deathbed, Jefferson freed just five slaves, relatives all to his “mistress” (if such a word is fair), Sally Hemings.

Hamilton leans into this fact when Alexander Hamilton, played in the new Disney+ movie by Miranda himself, mocks Jefferson (Daveed Diggs) for his hypocrisies in a rap battle.

“A civics lesson from a slaver,” Hamilton seethes in the show. “Hey neighbor, your debts are paid because you don’t pay for labor. ‘We plant seeds in the South, we create?’ Keep ranting, we know who’s really doing the planting.”

It’s one of the many flashy moments where Hamilton brandishes the anti-slavery sentiments of its title character, going so far as to suggest if he hadn’t died in a duel in 1804 he could’ve done more to end slavery. Throughout the show, he’s depicted as standing shoulder to shoulder with John Laurens (Anthony Ramos), who preaches “We won’t be free until we end slavery” during the American Revolution, and is even introduced as a young man horrified in his childhood on St. Croix as he watches “slaves were being slaughtered and carted away.” It was a satisfying message when the musical opened in 2015 with its color-blind casting, and it plays even more satisfying now.

However, like much else in regards to Alexander Hamilton’s life, the contradictions and shortcomings the man displayed toward slavery were thoroughly glossed over. Despite being an immigrant with a rags to riches story, Hamilton was also an elitist with those riches, favoring big banks and commercialism to the supposed agrarian utopia Jefferson imagined. Even the night before his fateful duel with Aaron Burr, Hamilton lamented to a friend that New England Federalists were fools if they really wanted to secede from the Union. Seceding would provide no “relief to our real disease, which is democracy,” Hamilton wrote, hinting at his disdain for popular rule.

The thornier side of Hamilton’s relationship to slavery is similarly overlooked. This is a fact Miranda is now publicly commenting on ahead of the Disney+ release.

In a recent interview with NPR, Miranda said, “[Slavery] is the third line of our show. It’s a system in which every character in our show is complicit in some way or another… Hamilton – although he voiced anti-slavery beliefs – remained complicit in the system. And other than calling out Jefferson on his hypocrisy with regards to slavery in Act 2, doesn’t really say much else over the course of Act 2. And I think that’s actually pretty honest.”

So what were Hamilton’s actual views on slavery? Well, as Ron Chernow notes in his biography, Alexander Hamilton, which the Hamilton musical is based on, “Few, if any, other founding fathers opposed slavery more consistently or toiled harder to eradicate it than Hamilton.” This is probably true, but it speaks more to how little that generation did to confront what became their new nation’s original sin than it necessarily speaks to Hamilton’s trailblazing abolitionist advocacy.

Born on the Caribbean island of Nevis in 1757, Hamilton grew up in a part of the world where slavery was an everyday aspect of life. Indeed, one of the primary reasons the Caribbean islands under British rule balked at the North American colonies’ calls for independence is they relied on the British Army and Navy to keep the local slave populations from uprising. There were eight times as many Black slaves as white colonists on these islands, a far higher ratio than the white colonists outnumbering Black slaves four-to-one in the North American colonies.

Hamilton saw this in his everyday life. After his father walked out on him, he went with his mother and older brother to stay with their in-laws, the Lyton family. Yet the Lytons were sugar planters who owned a vast amount of slaves, and one of the reasons they soon turned the Hamiltons out is because a relative stole 22 of their slaves and ran off to start a new life in the Carolinas—keeping those with dark skin in bondage, of course.

During this period in his life, Hamilton developed a strong distaste for slavery, which he considered barbarous. He even developed rather progressive opinions for an 18th century white man in the Caribbean, noticing there were no genetic differences in mental or physical ability between Black and white men. His ability to express vocal outrage over slavery impressed merchants early in his career, who eventually helped fund his education toward the mainland.

But what did he do with this knowledge? As Manuel said in 2020, clearly not enough. Upon reaching New York and quickly asserting himself as a brash intellectual leader in the Revolutionary generation, Hamilton supported anti-slavery causes, but they were never a high-priority. His dear friend John Laurens did speak out against slavery and even radically attempted to free 3,000 slaves if they fought for the Continental Army, beginning with the 40 slaves he stood to inherit from his father Henry Laurens, President of the Continental Congress. But while Laurens won approval for the plan in the Continental Congress, when he arrived in South Carolina to emancipate the said 3,000 slaves, he faced extreme opposition. Even as a member of the South Carolina House of Representatives, Laurens failed three times by overwhelming margins between 1779 and 1782 to emancipate 3,000 Black lives from chains.

Hamilton supported his friend Laurens’ cause, but he was personally busier with his responsibilities as George Washington’s aides-de-camp (a secretary). He was also working his way into intentionally marrying into a wealthy family like the Schuylers… a family that’s wealth was partially predicated on owning slaves.

In a fact completely ignored in Hamilton, New York was very much a slave colony and then state during the 18th century. While the smaller northern farms never reached the economic needs for chained Black bodies on an industrial scale, it still was a common, even fashionable practice to own a slave. Before becoming a late-in-life abolitionist, Benjamin Franklin owned several house slaves in his youth. And in New York City during the 1790s, one in five white homes owned at least one domestic slave for household chores. It was a status symbol.

For the Schuylers it was more than just one slave too. At his height of wealth, Philip Schuyler—the father of Angelica, Peggy, and Eliza—owned 27 slaves, tending to his mansion in Albany and his mills in Saratoga. And while Eliza herself became a staunch abolitionist in her old age after Alexander died, in her youth, she told her grandson, she was her mother’s chief assistant in running the domestic affairs and slaves of the house.

All of this is expunged in the Hamilton musical that depicts two of the Schuyler sisters as free thinkers. In reality, Angelica long maintained the practice of slaveholding after leaving her parents’ home… as might have Eliza.

There are several ambiguous documents that would seem to suggest early in their marriage, Alexander and Eliza either bought, rented, or at least provided financial support in others’ purchase of slaves. After his wedding to Eliza, Alexander wrote Gov. George Clinton that “I expect by Col. Hay’s return to receive a sufficient sum to pay the value of the woman Mrs. H had of Mrs. Clinton.” Biographer Forrest McDonald argued that this was too small a sum of money to buy a slave and rather it was the salary for a domestic servant, however others have speculated it was essentially for the renting of a slave.

Later in 1795, Philip Schuyler wrote to his son-in-law that “the Negro boy & woman are engaged for you” at the sum of $250. Hamilton even noted the transaction in his cashbook as “for 2 Negro servants purchased by him for me.” Biographer Ron Chernow argues that this purchase was possibly a reluctant service Hamilton did for his brother and sister-in-law, John and Angelica Church. But the best thing to hang on that is Angelica writing, regretfully, to Eliza that she and Alexander have no slaves to help host a large party. Yet to say there is an uncomfortable ambiguity there is an understatement.

To Hamilton’s credit, he was an early member of the New York Manumission Society, which fought against slaveholders kidnapping fugitive slaves and Freed Black people off the streets of Manhattan and selling them into bondage. The group petitioned the state’s General Assembly to pass a law that would phase out slavery in New York—a policy championed by Burr (before he reversed his abolitionist tendencies when he became a political ally of Democratic-Republicans and remained a slaveholder his entire life). And as the leader of the Society’s Ways and Means Committee, Hamilton drafted proposals that members of the group who owned slaves, including chairman John Jay, free all slaves over the age of 45 immediately; those younger than 28 by the time they’re 35; and those between 28 and 38 within seven years of the proposal’s writing. But even these potentially decade-spanning deadlines were considered too radical by the slaveholders of this anti-slavery society… they were roundly rejected and Hamilton’s committee was disbanded.

Still, Hamilton remained part of the group’s standing committee and even petitioned the state legislature of New York to ban trading slaves from anywhere else in the world, saying exporting Black people “like cattle and other commerce to the West Indies and the southern states” was a monstrous affair.

Nevertheless, all of these stands were made before Hamilton had actual political power inside of the government, as opposed to writing to it. So what did he do when he actually was in the room where it happens? Largely nothing other than treating it as a bargaining chip. During the Constitutional Convention, Hamilton spoke passionately about the need for allowing easy immigration and U.S. citizenry to anyone who wanted it—and argued that senators should have lifetime appointments—but on the issue of slavery, and the infamous “Three-Fifths Compromise” that occurred there, Hamilton gloomily surmised, “No union could possibly be formed” without it.

And what of his visceral admonishment of Jefferson’s hypocrisies in 1796? It was vividly fair. Jefferson, ever the proud renaissance man, was aware that slavery was evil. He attempted to blame the institution on King George III in the Declaration of Independence before Southern states forced him to take it out, and in the early 1780s he published Notes on the State of Virginia, which among other things argued that slavery could be ended in the state by 1784 with emancipated slaves moving into the interior North American continent. Of course none of that happened, and between his many impressive positions in government, from ambassador to France to Secretary of State, to vice president, and finally President of the United States, he never actually acted on these goals… or freed the hundreds of Black men and women he kept toiling at Monticello.

In fact, Hamilton used the hypocrisy and blatant racism within Notes on the State of Virginia against Jefferson, noting the document’s paternal bigotry where Jefferson offered pseudoscientific explanations to suggest in the natural hierarchy, whites were above Blacks, in the way Blacks were above orangutans. “[He’d have them] exported to some less friendly region where they might all be murdered or reduced to a more wretched state of slavery,” Hamilton wrote as Phocoin about Jefferson’s unrealized emancipation plan. But his most damning indictment was insinuating that the well-noticed light skinned slaves called Black in Monticello might have a complicated heritage.

“At one moment he is anxious to emancipate the blacks to vindicate the liberty of the human race. At another he discovers that the blacks are of a different race from the human race and therefore, when emancipated, they must be instantly removed beyond the reach of mixture lest he (or she) should stain the blood of his (or her) master, not recollecting what from his situation and other circumstances he ought to have recollected—that this mixture may take place while the negro remains in slavery. He must have seen all around him sufficient marks of this staining of blood to have been convinced that retaining them in slavery would not prevent it.”

– Alexander Hamilton

Biographer Chernow even believes this hints at Hamilton having knowledge about Jefferson’s affair with the light-skinned Sally Hemings, as Angelica Schuyler Church was a friend of Jefferson’s during his time in Paris when he possibly began that, um, relationship. Hemings was 14 at the time.

Sadly, lest you think Hamilton was simply using the cloak of anonymity to call out the blatant hypocrisy of Southern planters, the uglier truth is that Hamilton was using this potential knowledge as a cudgel against Jefferson in the South. Writing in support of his Federalist compatriot John Adams, Hamilton rather cynically ends the essay by saying, “For my own part, were I a Southern planter, owning negroes, I should be ten thousand times more alarmed at Mr. Jefferson’s ardent wish for emancipation than at Mr. Adams’ system of checks and balances.”

So even in his most full-throated denunciation of slavery, the racism it’s founded on, and the hypocrisy of slave owners, Hamilton was still posturing it for political gain… among slave plantation owners.

For this reason, some historians, and even more activists, hold a wary cynicism toward Hamilton. Author and playwright Ishmael Reed even wrote a full-length lecture of a play called The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda, in which he depicts Miranda as a hapless dupe manipulated by Chernow into spreading manipulative lies about America’s founders, whom Reed compares to Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich.

This kind of broad portrait of these historic figures—or Miranda and Chernow for that matter—may be just as sweeping and reductive as the centuries of deification the founders and other “great white men” received before recent decades’ attempts by historians and universities to be more inclusive and objective about the historical record.

The truth about Hamilton, like most men, is a lot more complicated, including how Miranda’s impressive work of art presents him. Hamilton was a forward-thinker ahead of his time who understood slavery, and the basic tenets of racism that white society used to rationalize it, was insidious. “Odious” and “immoral” (complete with italicizations) were his favorite words to describe it. He made some nominal effort to fight it, but like a lot of white men throughout history, and even today, he ultimately placed it low among his priorities and often on the backburner… allowing it to linger to the next generation and the next century, and to the point where it nearly tore his beloved Union asunder in a civil war that claimed more than half a million lives.

Perhaps it’s best to remember, beyond musical stage glory, Hamilton was a man who did good and bad, and maybe cruelty by simply not doing enough when he had the power to do more. But instead of glorifying or vilifying those shortcomings, it’s best to learn from them and see how much (or little) we are doing today to overcome the legacy of slavery. It’s wishful thinking on the part of Miranda and Phillipa Soo’s Eliza at the end of the musical to say if Hamilton hadn’t died in 1804 “you could have done so much more” about slavery. When Burr shot him, his time in power had honestly passed. Ours has not.