The Connection Between Fez and 2001: A Space Odyssey

What does the indie platformer video game Fez have in common with Stanley Kubrick's classic 2001: A Space Odyssey? We take a closer look...

This article comes from Den of Geek UK.

In Stanley Kubrick’s seminal 1968 film, 2001: A Space Odyssey, astronaut Dave Bowman (Kier Dulea) survives the machinations of a malfunctioning computer – the sentient HAL 9000 – and is rewarded with a brush with the uncanny. We watch as Bowman enters a stargate before experiencing what can only be described as a cosmic rebirth: he experiences old age, death, some form of contact with an alien monolith, before heading back to Earth as an unblinking Star Child.

It’s the kind of ending that works as cinema rather than on paper, and filmmakers have drawn on its supernatural power ever since, whether it’s in the form of parodies or similar experiences where humans experience something far beyond their own limited understanding: Robert Wise’s Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, Darren Aronofsky’s The Fountain, and Alex Garland’s Annihilation are just a few examples.

In the realm of video games, meanwhile, there’s one game that comes closest to recreating the same sense of the unknown as Kubrick’s 2001 – the indie platformer, Fez. At first glance, it looks about as un-Kubrickian as you can get: a breezy exploration game with pseudo-2D graphics and a retro theme that draws on Metroid and The Legend of Zelda. But appropriately enough, given the technical ingenuity going on under the surface, Fez is a game with hidden depths.

When Fez emerged in 2012, it was immediately praised for its neat central mechanic, in which an apparently flat world can be rotated in 90-degree increments. While the action still takes the form of a traditional platformer of the 8- or 16-bit era, this one innovation completely changes how the game works: walkways that are unreachably far apart when viewed from one angle will become neighbors when viewed from another perspective. Otherwise hidden doors can be uncovered by rotating the world one way or another.

It was a clever idea that captured critics’ imaginations almost at a glance, which partly explains why an otherwise tiny game became so hugely anticipated over its five-year development span. Fez’s launch was also dominated, to a degree, by the outspoken character of its designer, Phil Fish – a French-Canadian whose controversial opinions on things like Japanese game development almost threatened to overshadow the game itself.

What a surprise, then, that Fez should emerge not just as a technically polished nostalgia hit, but as something even more ambitious: the gentle yet captivating story of an unassuming hero whose understanding of the universe is completely transformed.

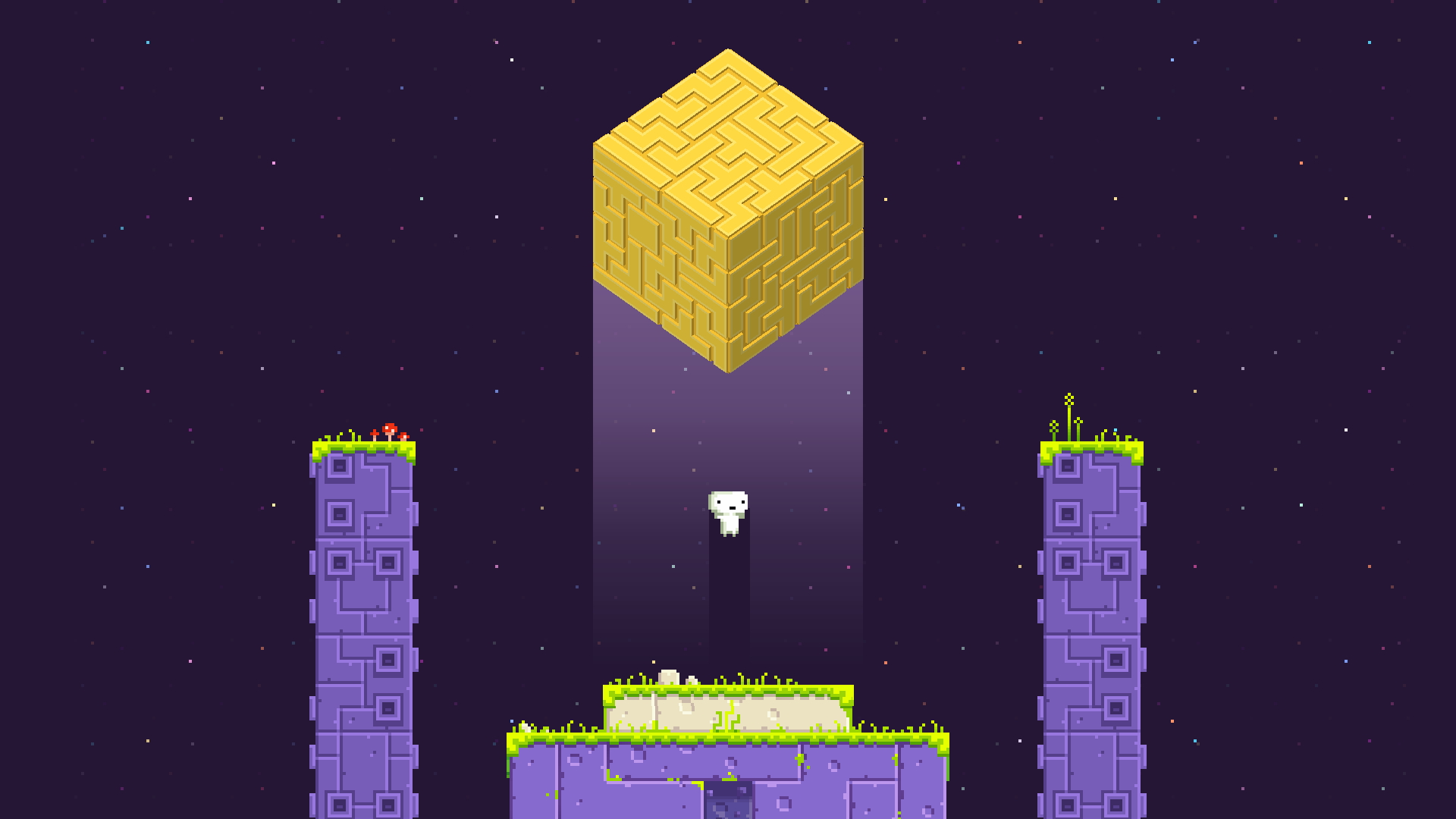

That hero is Gomez – a pale, diminutive character who, like millennia of heroes before him, leaves the comfort of his little town to go on an adventure. In the game’s opening scene, an apparently alien, golden cube shatters into myriad tiny pieces, each of them scattered around a colorful world of platforms and doors. It’s Gomez’s job to find all 32 of these cubes – some of them whole, most broken down into even smaller constituent parts. To help him, Gomez acquires his titular fez, an enchanted piece of headgear that allows him (and therefore the player) to rotate the environment. Only by collecting all the cubes can Gomez prevent the fabric of his reality from tearing itself apart.

The point of the story is that Gomez has only ever existed in a 2D world and has no conception of a universe with a Z-axis. As a result, the player can rotate the world and briefly see its effects (brilliantly, Fez’s landscape is made of thousands of tiny cubes, or voxels), but Gomez can only interact with it as a 2D character. He remains fixed in place as the perspective shifts, and can only move left and right, up or down once the world has completed its 90-degree turn.

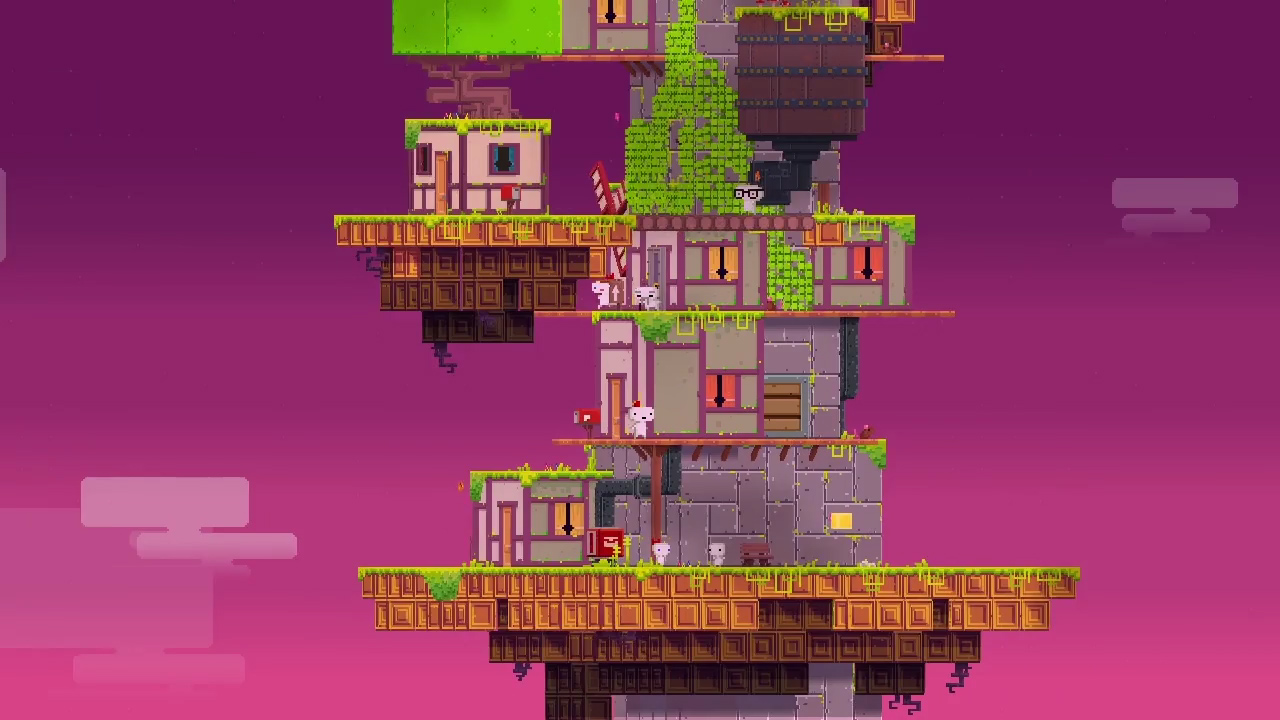

Through a mix of captivating pixel art and level design, Fish creates the illusion of an entire ancient civilization spread across a series of discrete stages: there are totem poles and statues and abandoned towns and wooden huts built on tree branches. There are old maps, runes, and hidden messages, all of which can actually be translated to uncover clues – figuring these out is vital to figuring out how to get hold of the 32 harder-to-find negative cubes dotted around the map.

Some of Fez’s incidental details hint at a greater underlying theme. Scholars have left behind notes and chalkboard scrawls. A huge telescope points up at the night sky, and you can look through and look at the stars and their constellations, shaped like the familiar pieces from Tetris. Almost wordlessly, and certainly without the clumsy sound recordings of some, much bigger video games, Fez conjures up a remarkably fully-formed and coherent world. In some instances, all the game needs is Disasterpeace’s stunning soundtrack to generate a truly eerie atmosphere.

And all of this builds to the first of the game’s psychedelic endings. Once Gomez finds 32 cubes, the final door is unlocked, the game appears to crash, and then he’s rewarded with a Bowman-like brush with the uncanny: the normal view of the 2D world gradually dissolves to a psychedelic zoom through a landscape of polygons and tetrominoes – a nod to the Stargate sequence, undoubtedly, but also a possible descent into the game’s code at its most abstract level.

When the player chooses a New Game Plus option, the meaning of all this is made clear. Gomez’s reward for finding the 32 cubes is a new ability: he can now view the world in three dimensions. Like Bowman before him, Gomez has achieved a new level of enlightenment that was previously beyond his understanding. There’s a clear parallel between the monolith in A Space Odyssey and the rotating golden cube in Fez. A translation of the alien language at the start of the game reveals that the cube is sentient and that its plan all along was to give Gomez the ability to see the 2D world in 3D. It’s a clear nod to the monolith’s role in A Space Odyssey, which is an alien object that subtly elevates our species along its various stages of evolution. In our prehistory, the monolith turns simple primates into weapon-wielding early humans. By the 21st century, it seems that we’re due another upgrade, as our advanced technology leads us to discover two other monoliths on the Moon and in orbit around Jupiter.

Gomez doesn’t journey through time and space in Fez, but his odyssey is hardly less mind-expanding. As other writers have noted, including this piece on Kill Screen, Fez‘s story appears to be at least partly inspired by the novella Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions by Edwin A Abbott. Published in 1884, it imagines characters who live in a 2D world much like the one Gomez lives in. Its protagonist, simply known as A Square, is visited by a three-dimensional sphere. Because of the square’s limited understanding, he sees the sphere as a flat circle. It’s only when the sphere takes the square to Spaceland, the three-dimensional world, that the square’s perception is finally broadened.

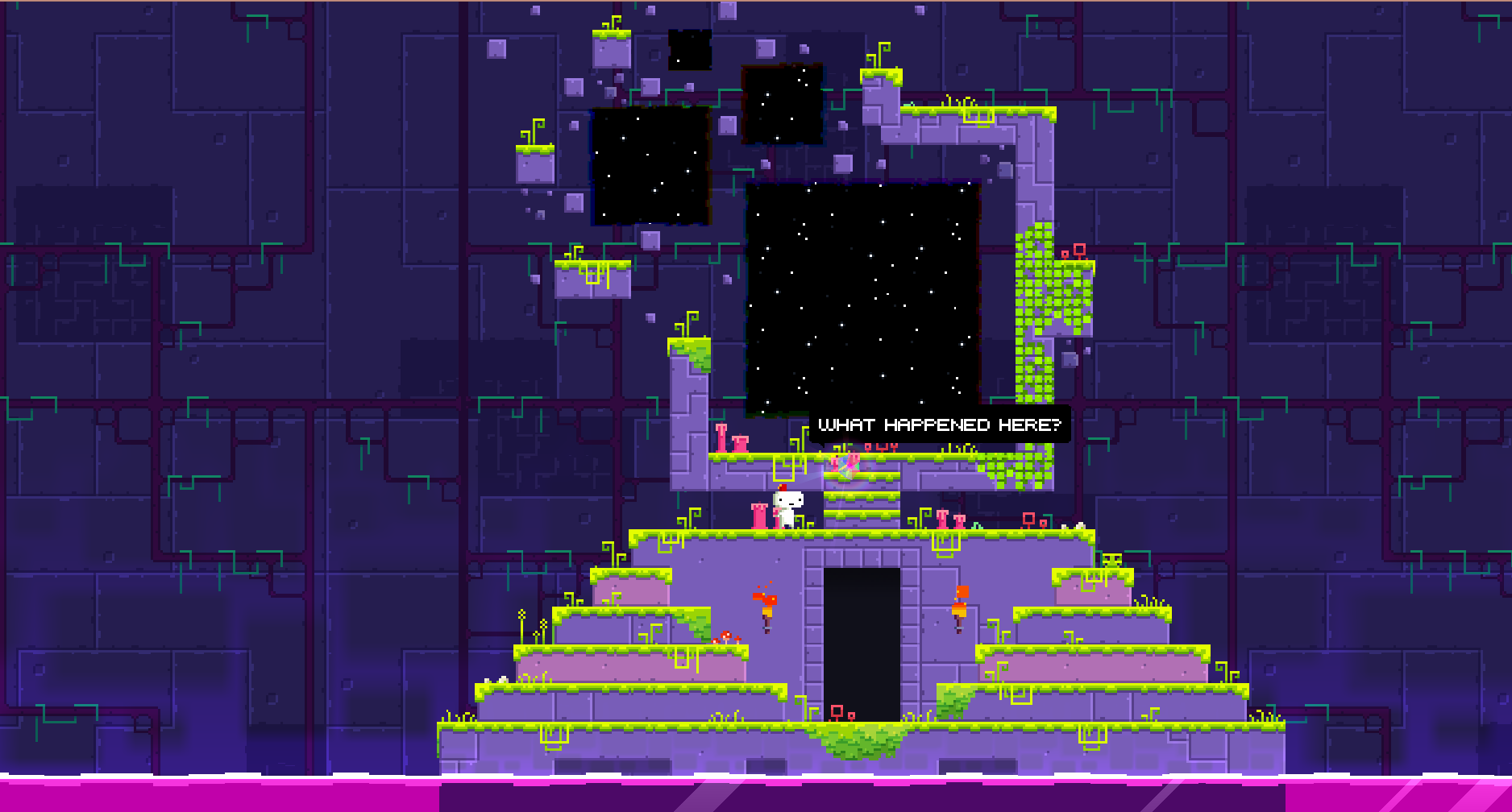

Fez appears to take the basic premise behind Flatland (or the various other pieces of writing inspired by it), connect it to the cosmic wonder of A Space Odyssey, and in the process create something quite unique in gaming. For one thing, Fez contains the same sense of mystery as Kubrick’s film. The whole game is full of hidden Easter eggs, obscure puzzles, and other secrets. A black monolith even shows up under certain conditions. A quick look around the web will reveal Reddit threads and forum posts about the theories behind the game’s unresolved questions. Its puzzles are so complex that the in-game references – a complex 3D map, old artifacts, and so forth – are barely adequate. As this video points out, Fez is one of those games where you’ll find yourself scribbling on endless bits of paper to translate all that alien text.

All of this merely serves to underline Fez‘s captivating sense of mystery – a mystery that recalls 2001: A Space Odyssey, yes, but also reaches further back to older stories of broadened horizons and mystical encounters. It’s possible to see echoes of Plato’s Cave – a story about a bunch of people whose only understanding of the real world is of shadows falling on the wall of a cave. It’s only when they escape the cave that they realize that there’s a much larger world outside, beyond their regular experience.

Even in the present, we’re still telling one another stories about what might lurk outside our everyday understanding. Take Elon Musk, for example, the tech billionaire who made headlines when he suggested that it’s overwhelmingly likely that we’re all living inside a Matrix-like computer simulation. In other words, we might all be just like Gomez – confined by the rules of a video game, but growing ever more aware that something else is waiting for us if we could just break its boundaries.

It’s telling that Gomez’s helper throughout Fez – a friendly little creature named Dot – is a tesseract, or a four-dimensional cube. A tesseract is, in essence, a shape used to describe the fourth dimension – a dimension that is typically as invisible to us as the third dimension is to Gomez at the start of the game.

Collect all the hidden objects in Fez, and the player’s treated to the second ending. The view of Gomez’s 2D world zooms out and out until it’s revealed that his planet is but one of a constellation of cubes. These, in turn, are all housed inside a tesseract, which is but one of an incalculable number of tesseracts that form the static of an old television.

Gomez might be a little chubby character in a quaint-looking video game, but we have far more in common with him than it first appears: we’re all tiny dots in an unimaginably vast universe. That Fez can communicate so many ideas, and so much wonder, within the confines of a retro platform game makes it one of the genre’s true classics. In its own colorful, playful way, this is nothing less than video gaming’s own Space Odyssey.