Why We’ve Always Been Wrong About the “Real” Super Mario Bros. 2

Super Mario Bros. 2 has long been considered the franchise's black sheep, but it's time to recognize it as the real sequel it's always been.

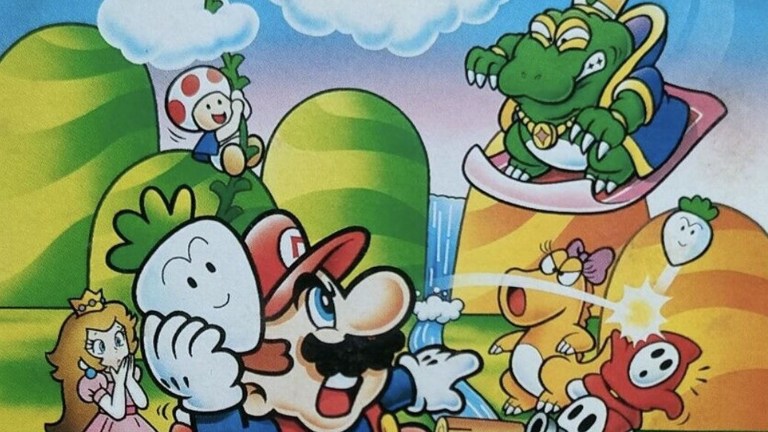

While Super Mario Bros. 2 is often considered the black sheep of gaming’s greatest franchise, it’s important to realize that label was applied retrospectively. When many of us first played that game that asked us to pick up turnips in a dream to battle a tyrannical frog named Wart, we said to ourselves “Ah yes, a Super Mario game.” After all, there was only one other game to compare it to (not counting the earlier Mario Bros. arcade title) and this one had many of the same characters and similar basic gameplay concepts.

As more Super Mario games were released, though, Super Mario Bros. 2 differences became much more apparent. At some point, the popular story behind that game’s differences began to take cultural root. The game those of us in the West eventually came to know as Super Mario Bros. The Lost Levels was the “real” Super Mario Bros. 2. However, Nintendo felt that game was too difficult for Western audiences. The Super Mario Bros. 2 got in the West was instead a Mario-themed version of a completely different game. You probably heard a similar version of that story at some point, and it always made sense given both the comparatively strange nature of that sequel and the number of games that were deemed too difficult for Western gamers at that time.

Yet, much like the story of blowing air into your NES cartridges to fix them, the story of Super Mario Bros. 2‘s origins has become so twisted over the years that you can only consider what we thought we knew to be, at best, a version of the truth. As is typically the case, the true story is so much more interesting.

I’m Afraid You’re Just Too Darn Difficult

First off, the playgrounds did get some of the facts right. The Japanese version of Super Mario Bros. 2 was considered to be too difficult for Western audiences. It was famed Nintendo Power creator Howard Phillips who made the decision to not import the Japanese version of the game for that reason.

At that time, Phillips was also responsible for testing certain imports to ensure that they met the company’s standard of quality and would be well-suited for the perceived desires of international audiences. When it came to Super Mario Bros. 2, Phillips’ problem wasn’t that it was difficult. Lots of Nintendo games were difficult. No, Phillips’ problem was that the game was difficult to the point of no longer being fun to play.

“As I continued to play, I found that Super Mario Bros. 2 asked me again and again to take a leap of faith and that each of those leaps resulted in my immediate death,” said Phillips of the Japanese version of the sequel. “This was not a fun game to play. It was punishment. Undeserved punishment. I put down my controller astonished that Mr. Miyamoto has chosen to design such a painful game.”

In the age of “git gud” culture in which the chronically online enjoy equating one’s love of gaming with their mechanical abilities, Phillips’ comments may seem like the overprotective whims of another suit. However, he had a point. Super Mario Bros. 2 wasn’t just exceedingly difficult; it was specifically designed to emphasize such difficulty.

Tasked with directing his first game ever, the now-legendary Takashi Tezuka decided to make things easier on himself by making them much harder on everyone else. Rather than re-write the book on Super Mario Bros. Tezuka elected to retain much of the considerable work that went into the previous title and focus on offering a more challenging version of that experience. As Miyamoto later stated, the team had so much fun making and testing harder Super Mario Bros. levels that they assumed experienced players would feel the same. Concessions were made for less experienced players (including the addition of cheat codes), but the goal was to design the game for what Super Mario Bros. 2‘s retail box later referred to as “super players.”

It was a fascinating approach that was both relatively unheard of at the time and kind of hard to imagine in retrospect. It was rare for a game to celebrate its difficulty and make it part of that title’s “appeal.” The commercial for Super Mario Bros. 2 even emphasized Mario dying just to let people know what they were in for.

While that approach feels slightly more common in a modern time where more games are made and sold based on their difficulty, it’s still wild to think of Nintendo doing such a thing. The company generally aspires to ensure that its major games are as accessible as possible, especially when it comes to Super Mario. Even back then, the company was concerned enough about in-game difficulty to have someone monitor imports for possible balance issues. “Nintendo hard” is a real thing, but Super Mario Bros. 2‘s design and release make it a true anomaly in the considerable history of gaming’s most influential company.

However, the strangest aspect of the Japanese version of Super Mario Bros. 2 is also the game’s most seemingly normal quality in retrospect: its familiarity.

Think back to prominent sequels of that era such as The Adventures of Link or Simon’s Quest and consider just how different they were compared to the previous game in those series. At a time before the gaming industry became quite so homogenized, the idea that a sequel should offer something entirely different was far more popular. It was a philosophy inspired by the crash of ‘83 which was partially caused by too many similar games flooding the market. Globally releasing a Super Mario sequel that was essentially just more Super Mario was seen as a risky move. Difficulty was one thing, but what kind of message would Nintendo be sending to their international fans if they decided to do that?

Thankfully, another Super Mario game was being developed at that time. It’s just that nobody involved with that project referred to it as a Super Mario game quite yet.

Miyamoto’s Super Mario Bros. 2

There is one other popular perception regarding Super Mario 2 that is so widespread that Howard Phillips even mentions it in the quote above. While Miyamoto was involved with the development of the Japanese version of that game in several capacities, he had a lot of irons on the fire at that time (not the least of which was a little game called The Legend of Zelda). That meant that large sections of the game were ultimately entrusted to Tezuka. It’s not entirely inaccurate to attribute that game to Miyamoto, but blaming its nature on his decision-making is a bit of a stretch.

However, Miyamoto was thinking of the future of Super Mario at that time. Not long after the release of Super Mario Bros. a team led by Miyamoto started playing with the idea of turning the side-scrolling genre into a vertical-scroller. They specifically hoped to create a two-player game that emphasized the ability to use objects to effectively create ladders to new areas. Alternatively, you could just throw your partner upwards. It was a seemingly simple concept that was also in line with Miyamotos’ greater desire to think outside of the box (even if only in increments).

The problem was that it was always little more than a neat idea. According to producer Kensuke Tanabe, Miyamoto’s early vision for a new Super Mario game was certainly different, but they couldn’t crack how to make it fun, especially for solo players. Ultimately, Miyamoto felt that they needed to use more Mario-like gameplay as the basis for their project and build new ideas atop that foundation. It’s just that nobody knew when they’d be able to put significant work into that concept or what form it would take. Most likely, they’d have to wait for the development of Super Mario Bros. 3.

However, the opportunity to revisit that concept earlier than expected presented itself when Tanabe was asked to make a game to help promote Fuji’s Yume Kōjō technology expo. Fuji saw that expo as their version of a “World’s Fair” event meant to showcase the future of various media and technology fields. The specifics of the game didn’t seem to matter much. They just wanted Nintendo’s contribution to be as innovative as the other products on display at the expo and for it to feature the festival’s mascots.

Well, it just so happened that Nintendo had put a lot of work into a pretty innovative prototype that was just a few tweaks away from meeting their standards. Once those tweaks were made, it was a relatively simple matter of inserting the Yume Kōjō characters in the game and designing the rest of the experience around those mascots’ vague One Thousand and One Nights theme. That’s how we eventually ended up with the game popularly known as Doki Doki Panic (full name Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic). When that game was eventually released to the public in Japan, it was a massive hit.

Doki Doki‘s success is an important and often forgotten part of this story. The popular version of what happens next is based on the idea that Nintendo desperately wanted to give Western audiences a new Super Mario Bros. game. So, they decided to convert Doki Doki Panic into a Mario game as a quick solution. However, that’s only partially true. Nintendo of America wanted a new Super Mario game, but they also wanted to find a way to get Doki Doki into Western markets. Nintendo just recognized that Western audiences wouldn’t know what to make of the game’s characters and themes. So they decided to reskin the game with Super Mario characters and kill two birds with one stone.

Numerous changes were made to Doki Doki‘s looks and themes during that conversion, but it’s hilarious to consider how the things that weren’t changed ended up impacting the Super Mario Bros. universe. Characters like Shy Guys, Birdo, and Bob-ombs that were created for Doki Doki are now iconic parts of the Super Mario franchise. Even the idea of Luigi being taller than Mario was necessitated by the fact the Doki Doki character Luigi was replacing was taller than the rest.

That isn’t to say Nintendo was being lazy. On the contrary, they took the opportunity to make numerous improvements to Doki Doki. It’s just that it proved to be surprisingly easy to convert a game that was originally envisioned as a Super Mario prototype into…well, a Super Mario game.

And that’s the part of this story that has proven to be not just easy to forget but difficult to talk about in the first place.

The “Real” Super Mario Bros. 2

The strange saga of Super Mario Bros. 2 doesn’t quite end with the game’s Western release. Thrilled by the quality of the changes made to Doki Doki Panic (and never one to pass up the opportunity to double dip), Nintendo later decided to release the converted version of that title in Japan as Super Mario USA.

For those keeping count, there was a point where we had Super Mario Bros. 2 (Japan), Doki Doki Panic, the Western version of Super Mario Bros. 2 (which was a reworked Doki Doki Panic), and Super Mario USA. Some were entirely different games, some were reimaginings of other games, and some were re-releases of those reimaginings. Yet, they all shared the quality of either being released as a Super Mario sequel or originally envisioned as one. It wasn’t until the 1993 release of Super Mario All-Stars labeled one of those projects as the Lost Levels and one as Super Mario Bros. 2 that Western gamers began to enjoy at least a little clarification about one of the strangest sequel origin stories in media history.

Except that’s not exactly what happened. All these years later, the idea that Western gamers were denied the real version of Super Mario Bros. 2 because someone felt it was too hard and instead forced us to settle for a Super Mario-themed version of some other game remains quite prevalent. It’s not hard to see why. It’s a simple, fascinating story perpetuated by Super Mario 2‘s black sheep status. By comparison, telling the true story of that game takes…well, just look at everything above you and realize that’s only part of this story. Much of that information wasn’t even available to the public until the last 10 years or so.

But perhaps it is time that we all became comfortable with what once seemed like a blasphemous statement: the Western version of Super Mario Bros. 2 is the real Super Mario Bros. 2.

That’s not a knock against Lost Levels. That’s an incredibly fun game that’s particularly popular among the hardcore fans it was designed for. It’s just that it really did push the limits of entertainment relative to its difficulty and probably would have infuriated many a young gamer whether we’d like to admit it or not.

More importantly, that “other’ Super Mario Bros. 2 has always been a Super Mario game in spirit and, eventually, name. It was also a game that addressed the other big problem with simply porting The Lost Levels: that game just wasn’t different enough to meet the expectations for a Mario sequel that Nintendo had set for themselves and have continued to set for themselves over nearly four decades.

Maybe you don’t love Super Mario Bros. 2. Maybe you still think it’s a little odd. It is, however, the game that best represents the standards we came to associate with that franchise and the company that made it. Don’t just take my word for it. It has long been Miyamoto’s favorite Super Mario game.