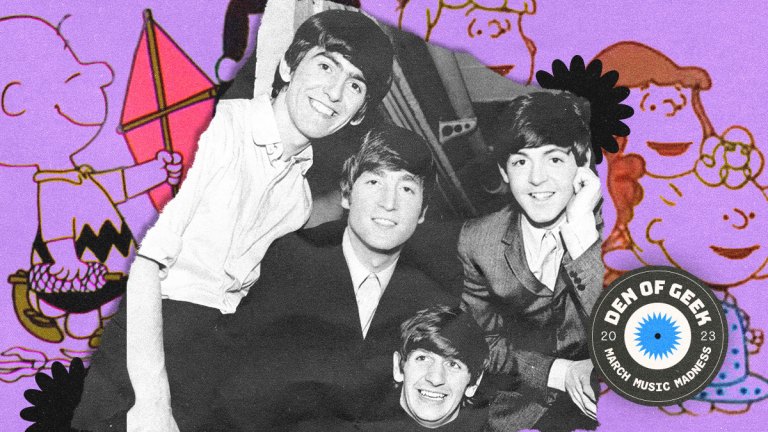

How The Beatles and Peanuts Creative Team Bonded at the Oscars

The Beatles pulled an Oscar out from A Boy Named Charlie Brown, but the Peanuts gang were happy to be at the table.

“Happiness is a Warm Gun” isn’t the only connection between The Beatles and Peanuts. Both groups exemplified the optimism of the 1960s era. Charles M. Schulz’s Charlie Brown was so assured of positive outcomes he repeatedly tried to kick a field-goal-placed football held by the town’s resident five-cents-a-session psychiatrist, Lucy, in spite of the knowledge she would pull it out from under him at the last moment. He faced defeat and realized “the world didn’t come to an end.”

When Schulz’s comic strip moved into animated TV specials, much of that expectant wonder was expressed through the music. Jazz pianist Vince Guaraldi joined the Peanuts’ creative gang in 1964, when he was hired to score a TV documentary about Schulz, A Boy Named Charlie Brown. The documentary never aired, but jazz label Fantasy Records released the Vince Guaraldi Trio’s soundtrack, Jazz Impressions of A Boy Named Charlie Brown in December 1964. The album was a crossover hit in the midst of the Beatles’ domination of the charts.

The earth shook when The Beatles conquered America, changing the cultural and musical landscape, and rendering many old-school entertainers obsolete overnight. “In the early 1960s when the British Invasion was beginning to hit our shores, the influence it had over venues presenting live music was pernicious,” says Derrick Bang. The Peanuts historian was discussing recent reissues of Guaraldi’s It’s The Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown (Original Soundtrack Recording) and Jazz Impressions of Black Orpheus.

“Jazz musicians were losing places to play because the clubs wanted rock acts,” Bang tells us. “The Greater San Francisco Bay Area, where Guaraldi was living, responded to the British invasion with our own crop of what very quickly became extremely popular bands.”

The Bay area quickly became a mecca for the new beat music. “Bill Graham built a new infrastructure for the music business,” explains John Lingan, author of A Song for Everyone: The Story of Creedence Clearwater Revival. The community became renowned for rock music venues. The rise of radio-friendly pop tunes drowned out a lot of jazz sounds, and many traditionalists tried to swim against the tide, mocking the music as teeny bopper noise, and hoping things like Beatle wigs would be a passing fad.

“Guaraldi did not run away from this, however,” Bang says. “He was very quick and in fact, quicker than many jazz musicians to incorporate pop into what he delivered. Whereas, in the 1950s, most of what he would perform during a club gig would be drawn from songs on The Great American Songbook. He has a great version of ‘Eleanor Rigby’ that became a very steady part of his set list as the 1960s moved into the early seventies.”

Throughout the decade, the Beatles provided the soundtrack to the generation, while Schulz’s Peanuts gang grew to reflect the children growing up during the period. By the 1970s, both groups were up against each other.

“The best story regarding their relationship with the Beatles was the fact that both Guaraldi and the Beatles were nominated for an Oscar the same year,” Bang says. “It was when A Boy Named Charlie Brown, the big screen film came out, and Guaraldi and John Scott Trotter and Rod McKuen were nominated for the song score. The Beatles were nominated for Let It Be.”

Directed by Bill Melendez, produced by Lee Mendelson, and written by Schulz, A Boy Named Charlie Brown, the first theatrically released feature Peanuts film, premiered on Dec. 4, 1969. Guaraldi’s soundtrack was nominated for Best Music, Original Song Score at the Academy Awards. It found itself in competition to the soundtracks to The Baby Maker, Darling Lili, Scrooge, and Let It Be, which was released in theaters in May 1970.

By the time the Oscars were presented, The Beatles had broken up. The one who announced their breakup, Paul McCartney, was the only band member to attend the pre-Oscar dinner. The Peanuts gang filled the extra chairs.

“Lee Mendelson tells a wonderful story of attending,” Bang says. “They wound up sitting at the same table with some of the Beatles. Well, all Mendelson wanted to talk about was what the Beatles were doing, and all Paul McCartney wanted to talk about was Peanuts. Of course, they lost to the Beatles. But as Mendelson said very cheerfully later, ‘If you’re going to come in number two, who better to come in number two to than the Beatles?’”

It’s The Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown (Original Soundtrack Recording) and Jazz Impressions of Black Orpheus are available on CD, LP, and digital formats.