It’s 30 Years Since The Animals Of Farthing Wood Traumatised a Generation

The Last of Us has nothing on The Animals Of Farthing Wood when it comes to traumatic deaths

Warning: contains a distressing description of cartoon mice infanticide.

The Animals Of Farthing Wood started out as a series of children’s novels by English author Colin Dann published between 1979 and 1994. But it’s the CBBC animated series than ran from 1993 to 1995 that really found fame. It was a French-British production (with a few other European countries involved) set in the English countryside and with a cast of regional British voices, which meant that it stood out against the great Nickelodeon, Cartoon Network and Warner Bros cartoons that defined TV animation at the time.

The first series adapted the first book pretty faithfully, and captured the franchise’s concept: the titular Farthing Wood is being destroyed by human developers, and the animals group together to travel to the safety of a legendary nature reserve called White Deer Park. It’s a great premise – an epic yet easily understood adventure with strong continuity, broken into episodic chunks. It was also educational, teaching a generation of city dwelling kids what a kestrel was, and clearly had an admirable ecological message.

But really, the series was a non-stop parade of death and despair. It functioned like a disaster movie or a slasher film, where a group of characters in peril assembles, only to have them slowly bumped off one by one. That’s not unusual for a Hollywood movie, but for a cartoon shown at 4 p.m. on weekday on BBC One, it had a staggering death toll. According to this video, an incredible 24 characters were killed across its 39 episodes.

While the second and third series adapted the later books set in White Deer Park, that first series is stunningly bleak right from the word go. The animals are literally refugees, with the families of smaller creatures like rabbits or mice often befalling the most harrowing fates.

For the Newts, There Was No Escape

The first characters to be written out are a family of adorable newts. Needing to live by water, they decide to remain by a marsh while the others go on. The marshland is soon set ablaze by a discarded cigarette, and while we never see their fate, the “Previously on…” voice over on the next episode ominously explains that “For the newts, there was no escape.”

That’s pretty minor league though compared to what’s to come. The pheasants, portrayed as a bumbling lovable old couple, are the next to suffer, and the first characters whose deaths we actually get to see properly. The animals come across a farmhouse, and as becomes the formula for most episodes, they think that it might be a safe place to hide out. But of course, there are humans, and wherever there are humans, there is danger. In this case it’s a farmer with a shotgun, who takes out the female pheasant.

Like most of the human characters on the show, we don’t see the farmer’s face, just his feet and the shotgun. The gun almost becomes anthropomorphised, with the two barrels looking like cold, uncaring eyes, starring back at us from the TV. What makes it so horrible is that after the pheasant’s death, the other characters actively make fun of her partner’s grief and one of the rabbits even pretends to play a mock violin in front of him! (How do woodland creatures know what a violin is?) Eventually the male pheasant proves himself to be a hero, going back to the farm to rescue Adder, who was left behind. But instead of this act finally gaining him the respect of peers, he is faced with the image of his wife’s corpse, now plucked and ready to be cooked, and while understandably freaking out about it, is also shot by the farmer.

Hapless Hedgehogs and a Thorny End for Baby Mice

Other characters meet their end in equally horrible ways. A young rabbit is shot in front of his parents. The hedgehogs, who are also portrayed as a sitcom-style old husband and wife, are killed when they are run over while the animals dash across a busy motorway. What makes it particularly harrowing is that this happens near the end of the series, and the motorway is really the final major obstacle between them and White Deer Park. They were so close. As the hedgehogs dawdle across the tarmac, they keep stopping in fear and curling into balls — when what they really need to do is keep moving. They’ve almost already accepted their end. The female hedgehog hopelessly begging her husband not to curl up in front of the incoming wheel of an articulated lorry has genuinely haunted me for years.

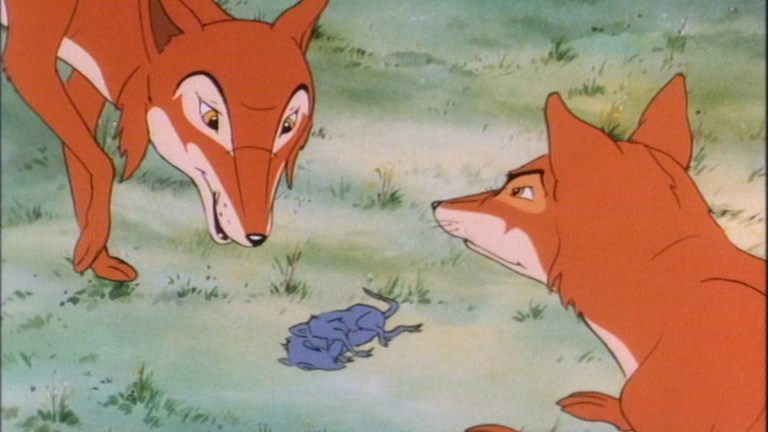

The most notorious image from The Animals Of Farthing Wood, though, comes during the seventh episode. The field mice have a litter of babies, and spend the majority of the episode keeping them safe. Eventually they decide to hang back a while as the rest of the party moves on. However, not long after, Hare notices a bird of prey flying overhead with a mouse dangling from its beak. As he rushes back, he discovers a scene that is really hard to believe was broadcast on kids’ TV. Hare finds the bird impaling the baby mouse on a thorns of a dead bush, with the mouse’s siblings having already had the same fate. Blood pours out of them. For most of the other deaths on the show, it cuts away right at the final moment. But here the camera lingers on the gory detail.

The Animals Of Farthing Wood fits in with a wave of bleak, depressing British animation from the late 1970s and 1980s. Films like Watership Down and the under-seen The Plague Dogs from the same team (which is somehow even more harrowing), the adaptation of Raymond Briggs’ Cold War graphic novel When The Wind Blows, and even The Snowman. And even though they’re not British, we could probably put Studio Ghibli’s Grave Of The Fireflies and even The Land Before Time alongside them as contemporaries. There is definitely modern television animation supposedly aimed at children that deals with some pretty big themes — look at Cartoon Network shows like Adventure Time or Steven Universe. But I can’t imagine we’ll be seeing anything with such a high death toll as Farthing Wood ever again.

This article was updated from 2016.