Grave Of The Fireflies: An Animated, Anti-War Masterpiece

As a tribute to the late Isao Takahata, we take a look back at his Studio Ghibli masterpiece: Grave Of The Fireflies.

The following contains spoilers.

The bombs fall with an eerie silence. Kobe burns, its population flees not to the deafening roar of explosions, but the soft drone of engines from above. This is the opening of 1988’s Grave Of The Fireflies, and its sense of dramatic understatement makes it all the more terrifying: the firebombs hit the ground with such a quiet thud that they almost seem harmless. But then we see how the conflagration spreads, and how buildings and entire neighbourhoods are enveloped in an instant.

Director Isao Takahata captures all these details because he experienced them first-hand. When American bombers laid waste to Japan in the last days of World War II, Takahata was a nine year-old boy living in Ujiyamada, an eastern city now called Ise. He witnessed the firebombs falling for himself, and how stealthily they consumed everything they touched. Separated from his parents, Takahata spent what must have been a terrifying night on his own on Tokyo’s burning streets; it was only the next day that he was reunited with his mother, who’d fled to a nearby shelter.

“Many TV shows and movies that feature incendiary bombs are not accurate,” Takahata told Japan Times in 2015. “They include no sparks or explosions. I was there and I experienced it, so I know what it was like.”

Decades later, Takahata would finally capture this moment forever in Grave Of The Fireflies: an animated adaptation of Akiyuki Nosaka’s novel fused with his own wartime experience. The result is one of the most powerful animated films ever made: a cruel moment in history told from the perspective of a young brother and sister.

Like Takahata, 14 year-old Seita and his four year-old sister Setsuko are separated from their mother as American bombers lay waste to the city of Kobe. The family home is destroyed in an instant; Seita grabs what belongings he can and flee for safety. Tragically, however, their mother is mortally burned in the raid, and with their father serving in the navy, Seita and Satsuko are left to fend for themselves in a city where food and shelter are in dangerously short supply.

A ghostly air of heartbreak hangs over Grave Of The Fireflies from its opening frame. It’s not much of a spoiler to say that Setsuko and Seita’s ending isn’t a happy one, since Takahata reveals this in the story’s opening. Instead, we’re left to watch helplessly as two ordinary, once happy children are gradually altered by conflict; what’s doubly sad is that the pair remain naively optimistic almost until the very end. Takahata once said that he took inspiration from a storytelling archetype familiar in Japanese culture: that of doomed lovers who take their own lives at the start of the narrative, with the rest of the story taking place in flashback.

Setsuko and Seika aren’t, of course, lovers – though events force them to rely on one another in a way that a young brother and sister typically wouldn’t – and neither do they take their own lives in the usual sense. Instead, they’re taken in for a short time by a distant relative – a somewhat cold and detached aunt on their father’s side – who grouses and gripes at having two extra mouths to feed in a household already short of food.

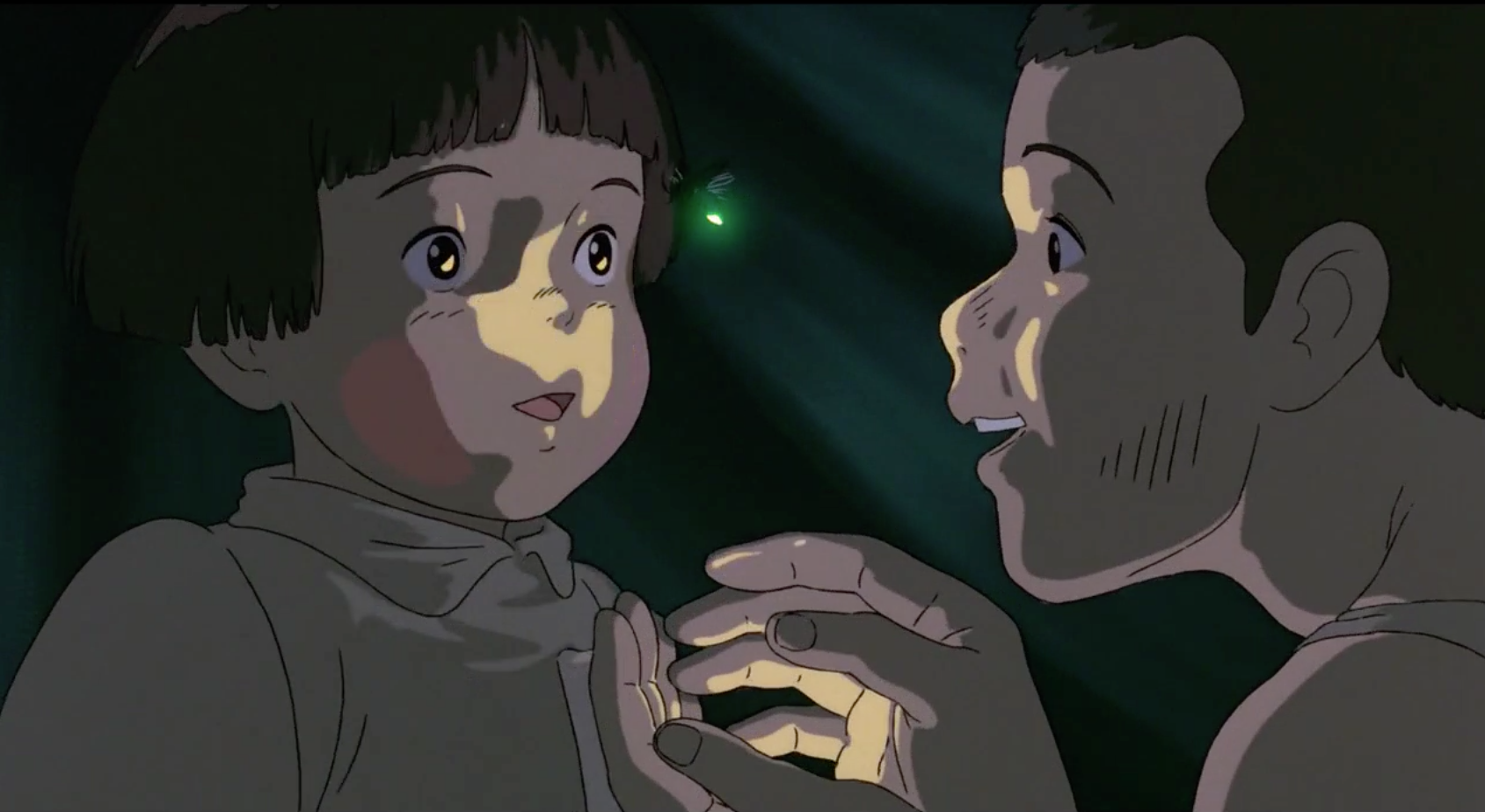

The hostility grows to the point where Seika takes his sister, their handful of belongings, and relocates to an abandoned shelter somewhere in the countryside; at first, they’re excited about their newfound freedom, away from their aunt’s barbed comments. As viewers, we’re painfully aware that, in their innocence, they’ve set themselves on a path to disease and starvation.

Like the bombs that quietly destroy entire neighborhoods, Takahata’s film is masterful in its depiction of quiet horror. Hand-painted though it is, the single image of Seika’s bandaged, bloodied mother is a searing one, and Takahata’s careful selection of small details hit with chilling accuracy: the writhing of a maggot, or the way Seika simply stands and stares in disbelief at what his mother has become.

Studio Ghibli’s exquisite use of animation in Grave Of The Fireflies acts as both an amplifier and a filter. By depicting the story through hand-drawn images, we’re distanced somewhat from its events; it’s often said that, had Grave Of The Fireflies been a live-action film, its heartbreak would have been too much to bear. But at the same time, the careful selection of details, from Setsuko’s youthful movements to the way a cat flees along a burning roof, create the sense of a coherent world that a director of live-action would have struggled to capture. When a live-action movie becomes too much for us emotionally, it’s easy to disengage; to remind ourselves that we’re watching actors performing in sets or running from special effects. Grave Of The Fireflies gives us no such escape route, because everything we see is as artificial as everything else – or, to look at it another way, everything looks and sounds real in the moment. Seika may be so much ink and paint, but her slow decline remains agonising to watch.

Grave Of The Fireflies was released in Japan as a double-bill with My Neighbor Totoro – Studio Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata’s gentle, soothing yet faintly melancholy story of post-war Japan and its shrinking countryside. That must have been a harrowing emotional rollercoaster for young audiences taken to Japanese cinemas in 1988, and it’s worth noting how the films illustrate their directors’ personal approaches to animation. Both go to painstaking lengths to create a sense of realism, but for very different purposes: in Totoro, Miyazaki creates a believable rendering of the Japanese countryside, into which he can place his mythical creatures and woodland spirits. Takahata, on the other hand, uses an inherently flat, two-dimensional medium to create an almost documentary-style realism. There are spirits in Grave Of The Fireflies, but they walk through a world that, even though it’s hand-drawn, feels concrete and filled with danger.

Although Grave Of The Fireflies is described as an anti-war film, the conflict itself forms only a small part of its tragedy. The true sadness in Takahata’s story is how cruelly the war makes people behave. We see the landowner who brutally attacks Seika for stealing some of his crops. The station guards who blithely step over the dead and dying. The aunt who, at any other time, would have probably been a decent if cold middle-aged woman, allows two children to wander off into an uncertain future. It’s not just bombs and a lack of food that kill in a war situation, Takahata seems to say, but an absence of compassion.

Takahata sadly died in April 2018, 30 years after his masterpiece’s release. Although less prolific and well-known than Miyazaki’s, Takahata’s movies remain an essential part of Studio Ghibli’s history: Only Yesterday, Pom Poko, and The Tale Of The Princess Kaguya, his final film, are stunning pieces of storytelling. Grave Of The Fireflies, meanwhile, is arguably Takahata’s most powerful feature – perhaps because it’s so steeped in his own childhood experience.

Unlike Takahata, Seika and Setsuko are too frail to survive the poverty and starvation that swept Japan in the aftermath of World War II, but Takahata is careful to show that their spirits linger on, both as a warning and a quiet rebuke: this is what we can do when we’re at our worst. We should, as a species, strive to be better.