Inside No. 9 Hoax Proves Broadcast TV Can Do What Streaming Can’t

Without getting all ‘old man yells at cloud’, sometimes TV tradition beats innovation.

All through the run-up to series eight of Inside No. 9, audiences were told to expect an episode called ‘Hold on Tight!’, set on a No.9 bus. Inside No. 9 is an anthology show, in which writer-actors Steve Pemberton and Reece Shearsmith take on different roles in each self-contained episode, alongside an impressive array of guest stars. ‘Hold on Tight!’, press were told, would be an homage to 1970s comedy On the Buses, and would feature guest star Robin Askwith, who is best known for his ‘cheeky’ 1970s sex comedy roles. Photos were released of Askwith, Pemberton and Shearsmith in costume next to a red London bus, and a movie-style poster was made. Clips of Pemberton and Shearsmith in their bus conductor costumes were included in the series eight trailer.

On the night the episode was due to be transmitted, at the last minute the continuity announcer told viewers that there had been a been a change to the schedule and Inside No. 9 would not be on. A quiz show would be aired instead. Quite a few viewers turned off or switched channel. The quiz show started, and there was no sign of Pemberton or Shearsmith. The game itself seemed to be somewhat like ITV’s The 1% Club, with which it shared a host, Lee Mack. Some, however, had noticed the strange coincidence of the title of this new show – 3 by 3…

By the episode’s final few moments, which we won’t spoil here, it became clear that this was this week’s episode of Inside No. 9.

Inside No. 9’s First TV Trick

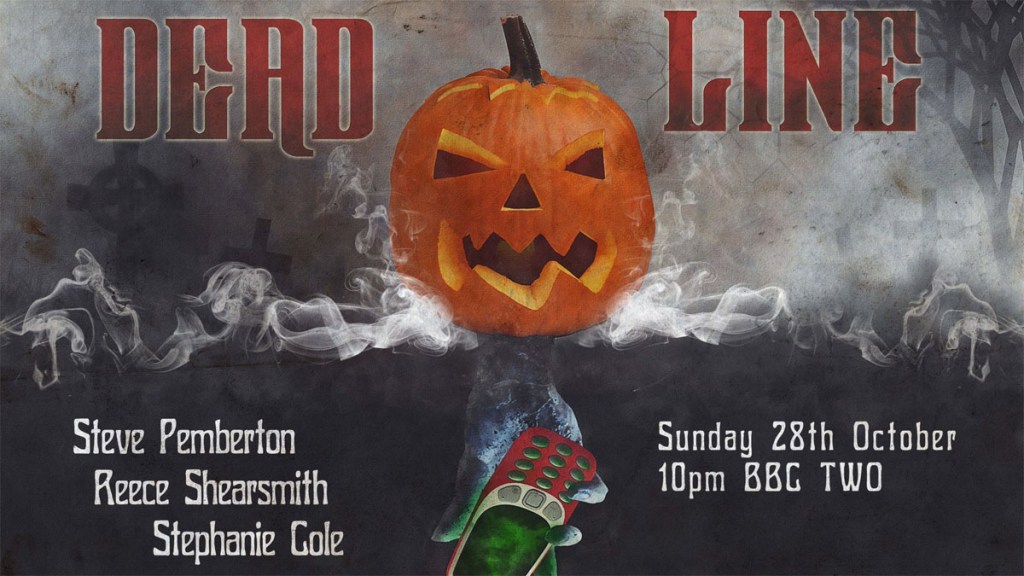

This is not the first time Inside No. 9 has pulled off this sort of trick. Back in 2018, Pemberton and Shearsmith teased a Halloween episode, ‘Dead Line,’ which was to be filmed and broadcast live. The plot, as advertised in press releases, was that a man finds a mobile phone in a graveyard and tries to contact the owner, with chilling consequences. Just over four minutes into the episode it appeared to be hit with technical difficulties, and then not long after that the continuity announcer came on to say that unfortunately there had been a technical problem and they would not be able to do the live episode. A repeat of series one’s silent comedy masterpiece ‘A Quiet Night In’ would be shown instead. A fifth of the audience switched channels.

Those who remained were in for a treat. ‘A Quiet Night In’ started playing and as Dennis Lawson sat in front of a large floor to ceiling window, not only could Pemberton and Shearsmith be seen behind him in footage from the original episode, but there was a new addition – a white figure that came right up to the window and revealed a skull-like face! At which point we cut back to the studio, and the real episode played out – an homage to Ghostwatch set in the (rumoured to be haunted) old Granada Studios. Ghostwatch itself was a scripted drama in the style of a documentary that infamously had many viewers convinced it was real when it aired in 1992. When Inside No. 9 did their story, they were able to enhance the feeling of reality by having Reece tweet live on camera, with the messages appearing in real time, bringing the audience in to the performance.

Neither of these brilliantly executed hoaxes work on streaming platforms. Of course, you can watch both episodes on BBC iPlayer and enjoy them, but to get the full experience, you had to watch it live, on BBC2, on the day and time it was scheduled.

That first hoax is primarily an effective way of using the live broadcast to do something unique; but the joke of the non-existent On the Buses episode is completely lost if you watch it on catch-up services. You go to iPlayer, find Inside No. 9, and there it is, episode five of series eight, ‘3 by 3.’ No mystery, no question, and the episode simply plays out as a very good but otherwise typical episode of the show, with only Pemberton and Shearsmith’s absence from any acting roles as a reminder that there was anything strange going on.

Inside No. 9’s hoaxes worked so well partly because they were so convincing. Technology failing during a live broadcast seems entirely plausible, and last-minute schedule changes are not unknown, usually as a reaction to a development in the news. In 2009, for example, Channel 4 cut the last few minutes of comedy show TNT at the last possible moment and had to have a continuity announcer make a brief apology, because the show had been intended to end on a joke about Michael Jackson, whose death had just been reported.

The Unequalled Live Experience

Playing with broadcast audiences is nothing new. In 2009, Comic Relief took over the continuity announcements on BBC Radio 4, with Jo Brand accusing Today presenter Sarah Montague of alcoholism, among other things. As recently as April, a ten-second teaser for the upcoming Doctor Who 60th anniversary specials was presented as a “Network Error” followed by interference and the breaking through of a signal revealing brief clips of Catherine Tate as Donna and David Tennant as the Fourteenth Doctor.

Messing around with viewers, playing jokes, and creating new idents is not the only advantage of weekly broadcast television. After a decade or so in which the ‘Netflix model’ of releasing shows in one big lump for people to binge watch became increasingly popular, some streaming services have started to go back to weekly episode releases. The weekly release format allows audiences to enjoy the experience of watching something and then waiting for a week, theorising and guessing what might be going to happen and sharing their ideas with each other before having them confirmed or denied by the next episode of the show. This makes sure that viewers of Star Trek: Picard or WandaVision have the same opportunity to discuss, theorise and build excitement for the finale as viewers of Peaky Blinders or Happy Valley.

Weekly release on a streaming service still cannot quite replicate the experience of watching something live. When it looked like David Tennant’s Tenth Doctor had been shot by a Dalek in 2008’s ‘The Stolen Earth’ and was about to regenerate into a completely unknown and unexpected new Doctor, the moment was enhanced by the fact that so many viewers watched it all at the same time, and could IM or text or even (it was still 2008 after all) actually phone each other straight away, knowing they had all just experienced the same shocking moment at the same time.

Before we get too much into the territory of Old Man Yelling At Cloud, there are of course major advantages to streaming, and ways of playing with the format of streaming shows that just are not possible for broadcast television. Black Mirror’s ‘Bandersnatch’, for example, is just one of a few experiments with Choose Your Own Adventure-style interactive television to have come out over the last few years. There are also still plenty of fans of the ‘Netflix model’ of releasing a show all at once, many of whom willingly wait until a weekly released show has released a complete season before watching.

‘Next Time On’ Spoilers

It’s also true that TV continuity announcers and trailers can be a curse as well as a blessing. Back in the day, the people who cut the “next week” trailers did not tend to be the people who made the series, and shows as different as Ballykissangel and Buffy the Vampire Slayer had major character deaths spoiled by trailers that showed the funeral and gravestone respectively of the unlucky characters. More recently, shows like long-running soap EastEnders and BBC drama The Split have been spoiled by well-meaning continuity announcers giving just a bit too much away.

In The Split’s case, it was a well-intentioned piece of advice on a helpline that gave away one character’s diagnosis of motor neurone disease. While streaming services indicate ratings and may provide advice on a helpline or similar, broadcast television is much more likely to follow an episode with “if you were affected by the issues in this episode” or to preface it with a warning.

Even this, though, can be turned to the show’s advantage sometimes. Downton Abbey series six, episode five (innocuously titled ‘Moving in a Farm’) had to come with a warning at the beginning of the episode that viewers might find some scenes distressing. While Downton Abbey had previously depicted (briefly and largely offscreen) rape, trench warfare, death from eclampsia in childbirth, a car accident, and a sudden unexpected heart attack during sex over its six years on ITV, it was still primarily a fairly genteel period drama that usually shied away from gore and did not require a warning, so this was notable.

The episode heavily featured dangerous 1920s motor racing, leaving viewers tense and expecting another car crash. But nothing happened. And then, late on in the hour when you had had more or less forgotten about the warning – Hugh Bonneville’s character Lord Grantham suddenly and completely unexpectedly spewed blood all over the dinner table and made the whole thing look like the set of Carrie. It was genuinely shocking, and very cleverly written in such a way that the obligatory warning made the racing scenes more tense than they otherwise would have been, without spoiling the actual shocker.

There are some types of show that thrive on broadcast television. If you have not managed to watch the latest episode of a reality show – even though it has been recorded months in advance – by the next morning and you are foolish enough to turn on morning television, you will likely have the latest development spoiled for you. If you want to record a live sports event and watch it later, you had better be prepared to avoid all TV, radio, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, and even a simple Google can bring up the latest result under a “News” banner if you are not careful.

The Comfort of a Schedule

There are also some categories of television that benefit from being broadcast as well as streamed. The BBC has two children’s channels, CBBC (for slightly older children) and CBeebies (for pre-schoolers). Plans to make CBBC online-only announced in May 2022 were met with disappointment, along with relief that CBeebies would still operate as a television channel. This is not because children cannot or do not want to use streaming services – they can and do (we happen to personally know a two-year-old who is alarmingly good at working iPlayer on a tablet to get straight to Andy’s Dinosaur Adventures).

But there is value in broadcast children’s television that you cannot get on streaming services. The broadcast of the same selection of short programmes at the same time every day (with variation on weekends) provides an almost subliminal sense of structure for young brains who do not yet know the days of the week, or understand why some days they go to nursery and some days they don’t. Children’s art can be displayed during a “show and tell” segment, and whenever there is a special occasion, pre-recorded links from familiar presenters tell young children all about Eid, Hannukah, Pancake Day, the King’s coronation, or whatever else happens to be going on around them.

Children’s presenters themselves become comforting, familiar figures that are as much part of the entertainment as the shows. And the only way to find Andy’s Dinosaur Adventures when you can’t read, don’t spend time online or reading reviews of new TV shows, and never watch trailers, is to watch the broadcast channel sometimes and see what is available.

Streaming isn’t going anywhere any time soon, and nor would we want it to. But we do hope that broadcast television won’t disappear either. As Inside No. 9 has reminded us, there are some things streaming services simply can’t do.

Inside No. 9 series eight concludes on Thursday the 25th of May at 10pm on BBC Two.