Alien: Earth – Noah Hawley On The Peter Pan Allegory of the First Alien TV Series

Exclusive: showrunner Noah Hawley and star Sydney Chandler guide us through the xenomorph's arrival in Alien: Earth.

This article appears in the new issue of DEN OF GEEK magazine. You can read all of our magazine stories here.

The future is soaking wet.

In the prequel series Alien: Earth’s vision of the year 2120, moisture seeps in everywhere you don’t want it to be. Damp rot creeps through the walls of a technocrat’s otherwise sterile compound, requiring hazmat cleaning crews to clear away the subsequent fungal growth. Climate change has flooded cities across the globe, rendering simple boats the most efficient form of local transportation. And then there’s the title creature itself: a glistening, drooling monstrosity that only a mother could love.

“Alien is such a distinct aesthetic,” Alien: Earth creator and showrunner Noah Hawley says of Ridley Scott’s hallmark 1979 film. “Something’s always dripping. It’s a very wet environment, and I wanted to translate that dynamic here.”

If anyone knows a thing or two about translation, it’s Hawley. The writer, director, producer, and author first came to pop culture prominence by adapting the Coen Brothers’ crime classic Fargo into a successful anthology series featuring five offbeat seasons for the cable network FX. He’s also responsible for a heady, psychedelic take on the X-Men mythos with the Dan Stevens-starring series Legion. Delving into the universe of the hallowed Alien franchise, however, represents a whole new xenomorphic beast.

Picking up two years before the events of Scott’s film, FX and Hulu’s Alien: Earth opens with familiar monochrome green text describing the state of play. The human population of a soggy Earth is on the hunt for immortality as five megacorporations—Prodigy, Lynch, Dynamic, Threshold, and a certain multinational called Weyland-Yutani—compete to achieve artificial sentience and control the future.

Left unsaid in that opening scrawl, but implicit for anyone who’s seen an Alien picture, is that the search for immortality will have to go through an extraterrestrial harbinger of death. And this time, H.R. Giger’s xenomorphic creation is coming to Earth’s doorstep as a monstrous payload aboard a crashing Weyland-Yutani vessel called USCSS Maginot.

While the Alien franchise timeline is a tangled knot—consisting of four mainline films, two often-ignored crossovers with the Predator franchise, two Prometheus prequels, the 2024 sidequel Alien: Romulus, and a heaping pile of video games, comic books, novels, and short films—Alien: Earth simplifies that continuity down to a more manageable focus on the original film and its James Cameron-directed sequel Aliens. This way, a xenomorph’s arrival to Earth is fully unprecedented without any “but the black goo in Prometheus!” qualifications.

Per Hawley, the logistical questions presented by the franchise’s canon aren’t integral to Alien: Earth’s mission: “There is surprisingly little mythology in the Alien film universe. All we really know is that there’s this company called Weyland-Yutani, and it has a knack for putting its employees in terrible danger.”

What’s more important is the feeling that a good Alien story instills. To capture that feeling, Alien: Earth harkens back to the very beginning.

“When I heard that they were making an Alien TV show, I was initially very hesitant,” star Sydney Chandler says. “Then I saw that it was Noah Hawley. He took the essence of Fargo and somehow created this entirely unique piece that still honors the essence of the movie. He’s done the same thing here. He’s created his own characters, his own world, his own obstacles and drama, but it still feels like it is honoring Alien on every page.”

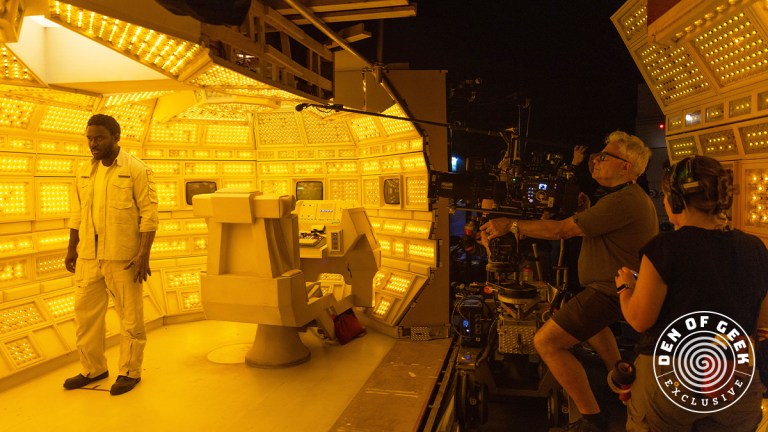

Designing the Retro-Future

The USCSS Maginot is not a perfect recreation of Alien’s doomed USCSS Nostromo, but it’s close. Familiar pallets dot the grated floors of the vessel’s claustrophobic halls. The crew (many of whom smoke like chimneys and sport distinctly late ‘70s/early ‘80s hairstyles) wake up from hibernation in identical pods and make their way to a mess hall that looks like it should already be covered in John Hurt’s blood. The mainframe room containing the supercomputer MU-TH-UR 6000, or “Mother,” has the same shape, lights, and iconography as its Nostromo cousin.

According to Alien: Earth production designer Andy Nicholson, the reason for these similarities goes beyond mere homage and into a more fundamental law of the universe: corporations are really cheap.

“The Yutani design motif for the Nostromo was so strong that any other ship of that period in the Yutani fleet would just take design elements from it,” he says. “I’ve been on both an aircraft carrier and a cruiser in the Royal Navy as part of research on previous shows. And the rooms are pretty identical on both, even though the ships are massively different. Because they know it works. It’s practical. It does a job.”

“There’s nothing new or shiny about Alien—no white walls or pristine costumes. There’s rust, and there’s grease. I love that that environment comes into this show,” Chandler adds.

The production design team meticulously studied imagery from the original Alien to match the look of the Maginot to the slightly larger Nostromo. Nicholson’s propmaster was even able to track down, from a manufacturer in China, retro-style 4:3 aspect ratio CRT TVs made with modern electronics for the ship’s displays. After drawing up plans for all of the Maginot sets, the team discovered original blueprints for the Nostromo in the Disney archives. They were delighted to learn their scaled-down version was mostly dead-on, save for a notable trick from the original design that had beguiled them.

“Just before we finished putting the ceiling on, we found out that they’d actually had the ceiling raised up and down so that if they wanted to change a shot, they had six to eight inches of movement—just enough that you can make a huge difference to what the framing was. It just was a masterclass in how to design amazing sets,” Nicholson says.

There were no blueprints, however, for crafting Alien: Earth’s depiction of life on a sweltering globe in the year 2120. Initially, the production staff started designing concepts and imagery for the series before a filming location was locked down. Once Thailand was selected, Hawley realized setting the Earthbound portions of the story in an urban Thai locale known as “Prodigy City” made the most sense. (Funnily enough, filming on the lugubrious Alien: Earth happened to coincide with The White Lotus season three’s time in Southeast Asia, though Hawley didn’t get the chance to reunite with his former Fargo star Carrie Coon.)

“My feelings as a filmmaker are always ‘let’s embrace the reality that we have around us,’” Hawley says. “Andor did amazing things with London and set extensions, but I didn’t have that kind of money. I thought that we should embrace Bangkok as much as possible. It’s going to be the most efficient and cheapest way to do it.”

“[Bangkok] is a city that’s gone from wooden architecture through the invention of concrete, and it was never colonized,” Nicholson adds. “So it’s got a very interesting look. There’s some wonderful ‘30s and ‘40s brutalist architecture in there. At the time when we designed and built the set, it was intended to be a city that could be anywhere [on the planet]. I’ve seen streets like that in Italy and Spain; you know, I’ve seen bits of buildings like that in America.”

The crashing of the Maginot brings the original Alien’s vision of analog sci-fi machinery into metaphorical and literal alignment with Earth’s sleeker futuristic cityscape of Prodigy City. The tactile feel of the Maginot combined with the blistering heat of the on-location Thai sets and 13 soundstages provided a beneficial sense of place for the cast.

“I love that the environment comes into the show. To bring in the heat and to bring in the sweat—it’s both gross and awesome. It’s fun going to the makeup chair, and your makeup routine is just dirt,” Chandler says.

Synths, Cyborgs, and Hybrids

Babou Ceesay wants to show us his arm. The British actor who plays Maginot security officer Morrow produces a crumpled envelope and reaches inside, pulling out a salmon-sized rubber appendage.

“They let me keep it,” he says, handling the floppy prop. “I was wearing it for 16 hours a day. We’d lube it up to get my arm in there. It’s three millimeters smaller than my actual arm, so it grips really tightly, which means I can use it.”

Morrow and his powerful paw are part of the Alien franchise’s long legacy of cybernetic characters. Ever since Ian Holm’s Ash was revealed as a secret robot in the original film, artificial intelligence has been as integral to the franchise as its gooey aliens.

Ceesay grew up in West Africa watching VHS copies of Alien films (“probably piracy somewhere there,” he admits) and, as such, was excited to embody one of the franchise’s signature synths. As it turns out, though, Morrow is not a synth but a cyborg in the series.

“Morrow’s like an iPhone 1 in an iPhone 20 world,” Ceesay explains. “I think he wishes he were all machine. Humans have foibles. Machines don’t. All those weaknesses, he wishes they didn’t exist.”

Putting its prequel status to good use, Alien: Earth recontextualizes the emergence of robotic helpers as a technological arms race akin to Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla’s competition over electrical currents in the 19th century. This time around, the five mega corporations on Earth are all experimenting with different methods of achieving cyberpunk immortality. These attempts take the form of cybernetically enhanced humans (cyborgs), artificially intelligent beings (synths), and synthetic beings downloaded with human consciousness (hybrids).

“Which version is [Tesla’s] AC or [Edison’s] DC?” Hawley ponders. “It’s about the next step for human beings. Is that cybernetic enhancement to the human body? Is it just synthetic AI? Or is it this transhumanism? If you have these three technologies in competition, inherently, that’s the battle for the future of humanity.”

While Morrow is the series’ resident cyborg, and Timothy Olyphant’s Kirsh its resident synth, it’s Sydney Chandler’s Wendy who operates as the story’s lead and its most radical technological allegory. The relationship between humanity and its machines is often symbolically paternal in science fiction, but Alien: Earth takes it a step further. The entity known as “Wendy” is the mind of a terminally ill child that’s been transplanted into the powerful body of a machine that resembles a young woman.

Wendy’s brain has to be prepubescent because adult minds are too “stiff” to make the jump to a new form. The human-to-machine transition was pioneered by young Prodigy CEO Boy Kavalier (Samuel Blenkin) at his lush (and, yes, damp) island lair. The name of said lair? Neverland, obviously.

“I had this instinct for Peter Pan as a classic metaphor about children growing up. And then when I delved deeper into it and re-read the book, I realized, ‘Oh, this is a horror story,’” Hawley says. “It’s super dark, man. Peter Pan is almost a sociopath. He’s a lost boy who doesn’t want to grow up, but of course, we need to grow up if we’re going to survive on this hot, wet planet.”

Since there’s no precedent for human-to-machine creations in the Alien canon, Chandler and the other performers portraying Prodigy’s “Lost Boys” hybrids had to get creative in preparing for the unique roles. This involved working with movement coach Daniel O’Neil and child development coach April Beresford to indulge in some childish activities like painting rocks, having sing-alongs, and trying out other preschool classics.

“On the very first day, our movement coach set up chairs in the center of the room, turned on some music, and said, ‘Go.’ We’re all adults who barely know each other, and now we’re playing musical chairs,” Chandler says. “That broke all of the ice for us as actors and as people and as characters. I think any group of coworkers should definitely do something like that because it allows you to throw away any preconceptions or fears.”

Establishing Wendy’s sense of childlike heroism also continues the Alien legacy in an understated but still important way. Amongst its generational peers, Alien has always stood out as a “female franchise,” as Hawley puts it. While similar sci-fi stories have often marginalized or even infantilized women, Sigourney Weaver’s Ellen Ripley defied her male crewmates’ expectations by proving to be the ultimate survivor. Though the youthful and naive Wendy is no Ripley analog, she continues her impressive legacy all the same.

“I genuinely don’t think I would have auditioned for [a version of Ripley]. You can’t do that. She’s her own character,” Chandler says. “There’s an incredible authentic strength that is portrayed in the Alien franchise through its female leads. And to be able to be a part of that, and to delve into that was a gift.”

Monsters, Old and New

The original Alien tagline accurately reports: In space, no one can hear you scream. On Earth, however, those shrieks come through just fine. Generating that terror for all life, organic or otherwise, on Alien: Earth is the franchise’s most iconic ghoul: H.R. Giger’s Lovecraftian xenomorph.

Operated by stunt performer Cameron Rodger Brown inside a suit, Alien: Earth’s killer is the spitting image of its foremothers. It’s a formidable sight stalking the twisted metal of the wrecked Maginot, even for the actors involved.

“The creature work was extraordinary,” Ceesay says. “Even before we got to filming, we did this screen test like an actual shoot. I hadn’t met Cameron yet, but he was already in the suit, eight-foot tall, that glistening drool falling out of his mouth. I felt anxious in that moment. My human nature just kicked in and said, ‘threat!’ There’s a big set of teeth right in front of you.”

“One of the things that made Giger’s xenomorph creature so horrifying was the fact that it never stayed in one state,” Hawley notes. “First it is an egg that a facehugger comes out of. You’re like, ‘I’m out. That’s the worst thing I’ve ever seen.’ Now it lays an egg in you that then hatches out of your chest, killing you. You’re like, ‘Now I’m totally out. That’s awful. That’s the worst thing.’ Then it grows to be 10 feet tall with two mouths.”

As evolution’s “perfect organism” and an enduring cinematic icon, the xenomorph’s design is all but impossible to improve upon, so Alien: Earth doesn’t bother to try. In the interest of presenting something novel, though, the show adds several more extraterrestrial critters to the Alien mythos. It helps that, unlike the Nostromo, the Maginot’s mission to discover, catalog, and capture alien life is explicit. The dimly lit rooms of the ship are dotted with tanks full of squid-like specimens just waiting to burst out and wreak havoc.

“I had to solve a problem,” Hawley says. “If I’m going to create an Alien story based on Ridley’s movie, I have to try to recreate every feeling that you had watching Alien for the first time. But after five other movies, I can never recreate the discovery process of that alien evolution of life. The only way I can do it is to bring in other creatures. I was just trying to solve a practical challenge for myself.”

Indeed, many of Alien: Earth’s innovations come down to simple problem-solving. The xenomorph is too perfect to improve upon, so new alien life must be introduced. Futuristic sci-fi automobiles are difficult to render, so boats roam a flooded Earth. The biggest problem for Alien: Earth to solve, however, is a simple question. A good Alien story isn’t just about whether humanity will survive but whether it deserves to. Confronting that question led Hawley straight to Neverland.

“I always say if you want to know where a character is on the moral spectrum, look at their relationship to a child in the story. Who is more human than a child, right? They’re bad liars. They don’t know how to pretend they’re not scared.”

In that respect, Wendy may be the first hybrid in the Alien mythos, but she’s far from the only child in a grown-up body. Up against a xenomorph, we all might as well be children.

Alien: Earth premieres with two episodes on Aug. 12 on FX and Hulu.