Why Dracula Adaptations Always Get Renfield Wrong

The nuance of Renfield's story is largely ignored in adaptations of Bram Stoker's Dracula. Will the character ever get the true exploration he deserves?

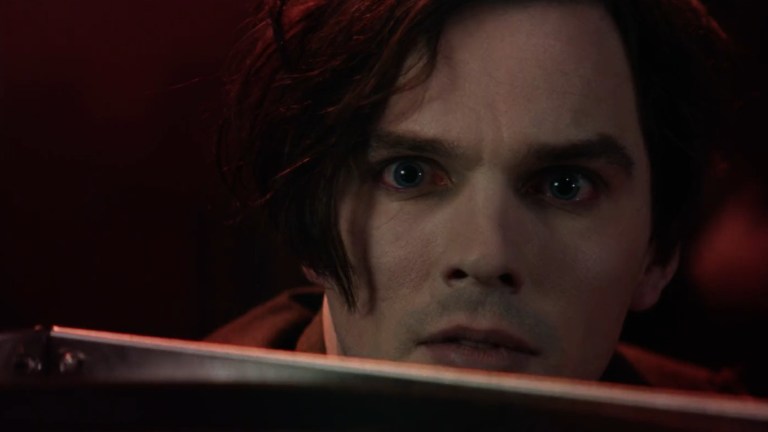

It sucks to be a stooge, so says Nicholas Hoult’s Renfield, the long-suffering servant of Count Dracula in the new Chris McKay comedy of the same name. Hoult plays Renfield as a lackey who has spent centuries having to deal with the whims and murderous demands of the boss from hell, played by Nicolas Cage in his long-awaited turn as history’s most iconic vampire. It’s not hard to see how Bram Stoker‘s novel would inspire a story like this. Ever since the beginning of cinema, adaptations of Dracula have positioned poor Renfield as somewhere between a zealous cult follower and a beleaguered personal assistant. Essentially, he is the Igor of any given take.

Yet the Renfield of the novel, the one who inspired it all, has a far trickier history that has seldom been explored on the big or small screen. A character defined in the novel as a mentally ill victim of intense cruelty from almost everyone he encounters has become better known to the public as a cackling sidekick to the Count. A century of pop culture rewrites has turned Renfield into someone with little to no similarities to his complicated origins.

R.M. Renfield is introduced in Dracula by John Seward, the doctor who oversees the lunatic asylum conveniently located near the count’s recently purchased English estate, Carfax. To Seward, Renfield is his most intriguing patient, one he conducts intense interviews with in order to understand his unique condition. He is described as being in his late 50s, “Sanguine temperament, great physical strength, morbidly excitable, periods of gloom, ending in some fixed idea which I cannot make out.” His delusions compel him to eat living creatures, including spiders and birds, which he hopes will allow him to gain their life force. Seward diagnoses him as a “zoophagous maniac.” Dracula has promised him eternal life through an endless supply of insects and rats if he worships him.

From the very first Dracula adaptation, the origins of Renfield were dramatically changed. In Nosferatu, he is renamed Herr Knock and is the employer of Jonathan Harker/Thomas Hutter, and shown to be a clearly malevolent figure. He remains a real estate agent, like Jonathan, in the 1931 Bela Lugosi film, and is the first employee sent to Transylvania. After falling under his spell, he returns to England as a cackling maniac in one of the film’s most iconic scenes. Indeed, it is this version that would influence future adaptations more than Stoker’s novel.

Werner Herzog’s ‘70s remake of Nosferatu reveals Renfield to be a perpetually giggling asylum patient and spreader of the plague that dominates the city. Francis Ford Coppola’s lavish adaptation, perhaps the best version of the book, cast the always-welcome Tom Waits as Renfield. This 1991 take gave him some more depth as a character but relying on the 1931 film’s changes by having him be Jonathan’s predecessor as Dracula’s lawyer in London. His madness is rooted in his encounter with the vampire, which, by the ’90s, was the new default mode of defining the character.

Renfield isn’t always a patient in Dracula adaptations. Sometimes, he’s just a guy with a terrible boss. NBC’s shambolic but occasionally fascinating one-season adaptation from 2013 made Renfield the most sensible person in the cast. Portrayed by Nonzo Anozie, this Renfield was a highly educated lawyer who became Dracula’s confidant because the vampire viewed them on equal terms. This dynamic, both in terms of class and race, had a lot of potential that the series sadly squandered, despite Anozie’s impeccable charisma. Writer-actor Mark Gatiss cast himself as Renfield in his and Steven Moffat’s BBC adaptation from 2020, turning him into Dracula’s lawyer who may or may not be under his thrall now and then. This aspect is poorly depicted in this messy and confused adaptation and you could easily remove Renfield from the narrative without changing anything. It’s a change that certainly gives Renfield more agency, and often a more active part in the plot, although it mostly seems to happen for reasons of narrative convenience rather than character-driven creativity. Sometimes, you just need a goon to tell everyone what’s going on.

Mainstream pop culture remains shaky at best when it comes to depictions of mental illness. Stoker’s own version of this is hardly a great foundation to adapt from, being so thoroughly rooted in Victorian notions of madness and how it should be dealt with. Yet it’s not without a degree of empathy. The only person who sees Renfield as human is Mina, which ignites his crisis of conscience and leads to his violent death. “Poor Renfield”, as the book describes him, is described as having been beaten beyond recognition, “his face [was] all bruised and crushed in, and the bones of the neck were broken.” There is pity from the others, but no real compassion. To Seward, he was an experiment. To Dracula, he was a pawn. Before his death, he is mostly viewed, both by characters and the narrative, as an object of grotesque fascination. Where Dracula’s devouring of blood carries an erotic slant, Renfield’s eating of bugs is horrid, beyond human in a way even the Count doesn’t approach.

Writers return to Dracula time and time again for adaptations because of the malleability of its themes. Vampirism endures over the centuries in fiction as it can be remolded to mean whatever you want, from sex and death to infection, racism, politics, and much more. There’s a reason scholars are still arguing over what Stoker intended with his much-dissected novel. No adaptation has ever been 100% faithful to the book. Most of them haven’t even tried to be, leading to major character changes to suit the writer’s motivations. Nobody is safe from this, yet the Renfield of it all is especially maligned, with the potency of the character’s ethical implications ignored.

Here is a mentally ill man, discarded by society and left to rot in an asylum, who is manipulated by those around him and eventually coaxed into becoming the plaything of a creature who sees all of humanity as his own personal puppets. Those who live with mental illness are far more likely to be hurt than to hurt others, despite the prevailing stereotype of their supposed dangerousness. In the book, it’s clear that Renfield was never going to receive immortality from Dracula, or any sort of happy ending. His fate was one of pain, of loneliness and of zero autonomy. That’s one of the most terrifying aspects of the story, and no adaptation has truly confronted that. It’s easier, and far more palatable to audiences, to go for one of the two neat tropes: eye-rolling personal assistant or giddy slave. Both versions exonerate the supposed heroes of the story, who don’t view Renfield with any more warmth than the vampire who kills him. Dr. Seward’s culpability in Renfield’s agony doesn’t end with any sort of epiphany. He gets his heroic moment and his patient doesn’t.

2023’s Renfield wants to offer a comedic look into the exhausting and often traumatic reality of having Dracula as your narcissistic and codependent boss. It might be the closest any Dracula adaptation comes to tackling the character’s mental anguish as a topic of respect, even if it’s repositioned as a relatable millennial hustle culture quirk. The prickly realities of severe mental illness aren’t something we necessarily see as compatible with our preferred takes on vampire fiction. Frankly, it’s viewed as too heavy for tales of bloodsucking and slaying. Yet, if vampirism can be a thematic stand-in for everything, why shouldn’t it make room for explorations of mental health?

Renfield’s story surely deserves it.