White Boy Rick director: ‘The American Dream doesn’t exist for some people’

Brit helmer Yann Demange talks about the challenges of making his first US movie, working with Charlie Brooker and those Bond rumours

This article contains potential spoilers for White Boy Rick.

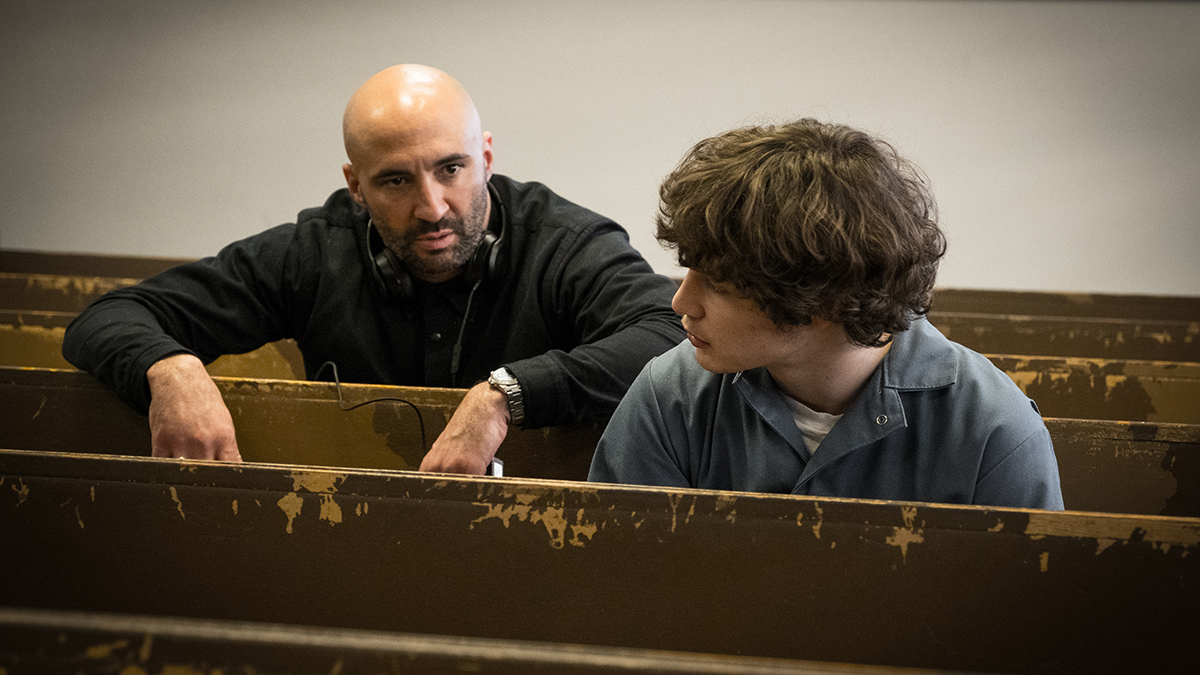

It’s hard to believe that White Boy Rick is only Brit helmer Yann Demange’s second feature film. After all, this is the man who was strongly rumoured to be a frontrunner for Bond 25 before Cary Joji Fukunaga was plonked in the director’s chair. If anything, that probably speaks to the strength of Demange’s first movie – Troubles-set thriller ’71 (for which he won best director at the British Independent Film Awards) – and his sterling TV work: overseeing the first series of East End gang drama Top Boy and the entirety of Charlie Brooker’s zombie-satire miniseries, Dead Set.

While White Boy Rick bears some similarities to Demange’s previous work, it also marks his first time working on an American movie. It’s a remarkably assured US debut, given that it came with the double challenge of working with a cast of experienced and esteemed screen stalwarts (Matthew McConaughey, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Bruce Dern, Piper Laurie) and, in the lead role, a rough-diamond first-time actor freshly plucked out of a high-school detention by a talent scout. Not bad for a lad from West London.

The film is a based-on-a-true-story thriller that follows the misadventures of Richard Wershe Jr. (played by newcomer Richie Merritt) – the youngest informant ever to be recruited by the FBI – as he infiltrates a drugs gang and then, after a dangerous descent into dealing himself, gets hung out to dry by his handlers (getting lumbered with a life prison sentence in the process). Set slap bang in the middle of the war on drugs in 1980s Detroit, White Boy Rick is a crime biopic that’s lifted by the affecting central relationship between the lost Rick and his irresponsible yet well-meaning blue-collar dad (another solid performance from McConaughey).

Demange is on jovial, sweary, candid form when Den of Geek sits down with him in London to chat about everything from the “burden” of translating true-life stories to the adrenaline rush of directing Hollywood legends… “You pinch yourself,” he says with a sincere, wide-eyed smile. “It’s still surreal. You still think, ‘Oh, it’s going to come to an end.’ There are moments like that where you definitely geek out.”

What was it that drew you to this real-life story?

It was actually a spec script that got me into it. I got sent an article about Rick a year before that script was doing the rounds, to see if I was interested in optioning it, and I couldn’t see a film I wanted to make in it. I couldn’t see a film that I felt personally enough.

So when I read the spec script, it was the father/son story [that stood out]. I was like, “I could see a story about a family that I’d like to tell.” But it came sort of shackled with a miscarriage of justice and an informant story. You had to tell those narratives to get to the one that, I guess, resonated with me the most personally. I mean, it’s not really a miscarriage of justice. He was guilty. The sentence seems a bit harsh. But the informant narrative is such an American staple and trope of the crime genre, that I just couldn’t get that excited about it, even though it’s quite extraordinary.

So I built the narrative around the emotional through line of the father and son’s relationship. Which I make like a bromance.

The relationship between Rick and his dad definitely stands out. Was Matthew McConaughey someone you wanted from the start?

He’s one of the people we mentioned at the start. I try not to fixate on someone. We met, and he’s just a natural fit. That character really believes in the promise of America. He has that belief and optimism in the American Dream. And Matthew embodies that. He’s a happy-go-lucky guy.

I needed someone like that, but someone that I hadn’t seen Matthew play before. There’s a tragedy to Rick Sr – a self-delusional quality to him. But yeah, Matthew embodied all the qualities I wanted for the character: someone who you just love and think will come out on top. But you know, that American Dream doesn’t really exist for some people.

Rick’s dad is a deeply flawed character, and yet he’s sympathetic…

That’s what I was interested in making. Like I say, it resonates personally. I’ve got a funky dad with funky philosophies on life and how things should be done – just offbeat.

I went to visit Rick a few times in jail. That’s when it really cemented that relationship with his dad for me – it was kind of a bit Oliver Twist. They’ve got their own set of rules, and their own little code. They’re bandits. They’re living outside of the system. But they’re wholeheartedly patriots as well, and believe in the American Dream.

There’s this dichotomy of how flawed Rick’s dad was, and how loving he was. To a certain extent, it’s the father’s fault that Rick ended up there. He was too busy trying to be a buddy, rather than trying to be a dad.

The casting of Rick himself – using a first-time actor – sounds like it was a risky prospect. How did that come about?

We took a risk. This was my first time in the States. I’ve street-cast a lot of the things I’ve done, with varying degrees of success. It’s always a Lotto. It’s always a crapshoot, as the Americans would say.

When I started looking for our Rick, I said, “Let’s do a two-pronged attack” – street casting and reading known actors. But I thought, in terms of authenticity, it might be exciting to take what is beginning to feel, to me, like a Hollywood version of the world, and to take a Hollywood star like Matthew and anchor him by putting him opposite someone that is just from the real world.

I mean, I read some wonderful actors, some brilliant ones. One really turned my head. I’m not going to name him. But he was slightly older. I wouldn’t have believed he was a teenager, and you wouldn’t believe that he’d grown up around the African-American community. That aspect didn’t feel authentic. The last thing you want is a white suburban privileged kid acting in that role. It just felt a bit off. But that’s only a reaction to what I was seeing.

In the process of street casting, one of the caster’s associates met Richie Merritt outside the principal’s office. He was getting in trouble, and she was pitching to the principal in Baltimore. He was like, “Ah, right, cool.” They kind of know about street casting, because The Wire was heavily street cast in Baltimore, so they know the concept of it. As they were walking out of the office, there was this kid, Richie, waiting, because he was in shit for some reason. And he said, “Well, you can start with him.”

They did a little improv, and they sent it to me, and I was like, “This is promising. I’d like to meet him.” And we took it from there.

It was a risk. In a way, he wouldn’t adhere to the shape of the film, or emote in the way you’d want him to emote. He keeps you at a distance, and at moments, you kind of go, “This could be such a movie moment, but his instincts from the street won’t let him do it.”

So you get an authenticity, but it’s kind of a strange performance. It’s interesting. It’s not the sort of performance you’d expect in a film like that. So I think it really helped. If anything, it helped anchor Matthew, because it meant that Matthew had to come down and meet him halfway, rather than the kid come up and be in a Matthew McConaughey film.

One thing that’s quite notable about White Boy Rick is the supporting cast. You’ve got some real legends there, like Bruce Dern and Piper Laurie and Jennifer and Matthew. Do you ever have moments where you geek out over that?

Yeah. Completely, man. I mean, Bruce Dern was the biggest geek-out moment for me in my career. And then meeting his daughter at Telluride, and her going, “I heard about you. My dad was telling me about you.” That was a massive geek-out moment for me, because I love Laura Dern so much.

I mean, Bruce Dern is a legend. He’s telling you a story. Most of them are just unrepeatable [laughs], but you’re hanging on his every word. I’m just like, “What a legend, and what amazing stories, and what an amazing spirit and a generous man.” I learned a lot. It was very humbling to see a man, someone of that age – Piper Laurie as well – with such a work ethic.

It’s that thing where they’ve got small roles but they make a very big impact…

Yeah. Bruce comes on, and you almost want the camera to stay with Bruce and go, “Fuck the rest of the film off. Let’s just make a film about this guy and his wife.”

White Boy Rick seems to share some similar themes with one of your earlier projects, Top Boy. Was that a conscious decision?

I think I’ve got a recurring theme with Top Boy and ’71. It’s boys looking for a sense of tribe and a sense of belonging, and ultimately having to go it alone. You know? And being outsiders. There’s an element of a personal thing that I project onto these stories.

I mean, they’re different stories, of course. But yeah, the obvious links would be “urban” and “drugs”. But let’s look beyond that, and think thematically. I think there’s a sense of young boys being robbed of the opportunity to have a childhood. That’s something that’s been close to my heart. And I think I’ve done the trifecta of it, and now I’m going to move on with the themes.

But subconsciously, I obviously keep going back there because I grew up in a particular way, with foster care and stuff, and the thing that really hurts me is kids sometimes – be it because of war, or because of poverty – don’t get the opportunity to have a genuine childhood. They’re sort of woefully exploited.

In terms of what speaks to you and what you want to carry on doing, what’s next for you?

You know, I found this one a bit of a burden, being a true story and having to cram it all into a film, and wrestle with trying to distil details – like, Rick had three kids, for example. Three different baby mothers. I had to distil them down to one. It was like an exercise in trying to take what should be a fucking miniseries, and chiselling it down to a film.

Next, I want to do a real, pure piece of fiction [laughs]. I’d like to do a genre film next. A straight-up movie. Like an Elmore Leonard-esque story with real Londoners. I’d love to do a Londoner film.

Talking about genres, you tackled horror a few years back with Dead Set…

It’s funny, I want to do a film that’s in that vein.

Is horror a favourite genre of yours?

Yeah. I like it when films have a genre bent. I’ve just done something for HBO like that [Lovecraft Country], where it’s about Jim Crow America, and there’s a monster attack. Jordan Peele and JJ Abrams are co-execing it.

In a movie, I’d like to do that. It’s not that I love horror for horror’s sake – but horror or action when it’s coupled with satire or commentary or themes that transcend its genre. It’s about something, but it’s fucking packaged as fun. I love that shit.

I loved Dead Set, and I loved working with Charlie [Brooker, the series’ writer] because he’s always got something to say. But he’s not soapboxing, and it’s not worthy, and it’s not earnest. Who needs that? But what was great was what he had to say about reality television and celebrity culture, and coupling that with a zombie attack – I was like, “I’m in! I’m definitely up for that.”

He’s obviously gone onto have massive success with Black Mirror as well. Could you ever envisage teaming up with him again in the future?

Mate, I’d love to, but I think he’s way too busy. A writer like that – why do a film? You have total control in telly. I mean, now, there’s an argument for— look at what he’s doing with Black Mirror. It’s like he gets to do six films a year. But I wouldn’t hesitate to work with Charlie again. He’s a fascinating guy.

Talking of Black Mirror as well, obviously, that’s graduated from Channel 4 and gone onto have this new life on Netflix – as is happening with the next series of Top Boy. What’s your take on the new age of TV?

Look, dude, I can’t pontificate on the state of television in the world today. Every day, someone’s spouting their opinion on it. Personally, look, it’s good news. There’s an explosion of content. There’s more content than there’s ever been.

I don’t know what it means for film, for cinema. All I know is that releasing this and ’71, you realise how difficult it is out there for films. Seeing Roma made this year for Netflix, and Paul Greengrass’s film [22 July] – you just think it’s incredible that a) they give these opportunities for these filmmakers and these movies to exist, and b) they’re taking such risks.

So personally, I’m all for it. I don’t know what it means. I don’t know what the future holds. But Top Boy was never going to be made for a third season. Which is a bit strange, that they cancelled it. It’s great that Netflix has given it a new lease of life. And it’s great that that cast who…a lot of them were non-actors – actually 38 of them. They were never going to do anything else. It’s great that they’re getting to flex that muscle again, and haven’t disappeared.

There were lots of rumours about you directing the next Bond movie earlier this year. How do you react to that kind of frenzied online speculation?

You just have to ignore it a bit. That became ridiculous. I was working on something. It got out of control. Everything was about that. I wasn’t caught up in it. I was oblivious to it. You’ve just got to take it with a pinch of salt.

Honestly, with humility, it’s kind of incredible that my name would even be associated with shit like that – where I come from and all of that. It’s very flattering and kind of strange, seeing your name thrown around like that. But that’s passed, and we move on. It’s cool.

White Boy Rick is out in UK cinemas from 7 December 2018