When Goldfinger Essentially Rebooted the James Bond Franchise

The third James Bond movie, Goldfinger, is in many ways also the first.

Imagine James Bond without a car. It’s not easy. Even in Ian Fleming’s early 007 novels, beginning with Casino Royale in 1953, Bond is obsessed with his supercharged Bentley and is constantly thinking about who is a good driver and who isn’t, and just how fast he or other people go—from allies like Felix Leiter to enemies in SMERSH and SPECTRE. Bond isn’t exactly the original fast-and-furious action hero driver, but when we think of the most famous suave secret agent, we have to imagine him behind the wheel of some kind of amazing car, one which almost always has hidden gizmos.

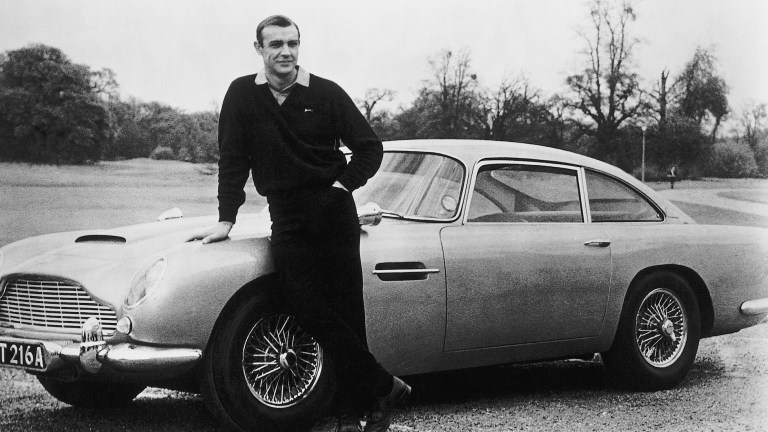

But it wasn’t until the third James Bond movie ever, the 1964 classic Goldfinger — which premiered in London on Sept. 17, 1964— that 007 got his famous Aston Martin DB5, complete with an ejector seat, slick weapons, and a spiffy tracking system. And, in a sense, Sean Connery behind the wheel of his silver Aston Martin is a microcosm of what Goldfinger did for the Bond franchise: utterly rebooted it to the point where we can’t imagine it any other way.

Bond Before Goldfinger

While Goldfinger is the third James Bond movie produced by Eon Productions, it was the seventh novel written by Ian Fleming and was originally published in 1958. Within the pantheon of the novels, Goldfinger was something of a comeback book, following the 1957 release of the book version of Dr. No. In fact, if you’ve never read the Bond books, Goldfinger is one of the classic texts that feels closer to the films than other Bond novels. Granted, a certain level of fidelity is broadly true of pretty much all the Bond films prior to Live and Let Die in 1973. They’re not straight adaptations, but you can recognize the books in those films, which is certainly not the case with most of the Roger Moore films, at all.

And yet, Goldfinger is the moment where the film franchise took one of Fleming’s stories and truly transformed it into something utterly new. The stakes and set pieces in the movie versions of Dr. No and From Russia With Love were impressive, but with Goldfinger, the scope was widened in the extreme. In Goldfinger, everything is turned up to eleven.

A New Mission

In the Goldfinger movie, Bond’s mission is to prove that legitimate gold broker Auric Goldfinger (Gert Fröbe) is smuggling gold illegally, and possibly using it to fund Chinese activities. However, unlike the novel, Bond essentially ignores his orders outright from the very beginning of the movie. If you’re trying to follow the actual plot of cause and effect onscreen, you’ll find that nearly everything Bond does is a broken promise. He tells Felix Leiter (Cec Linder) they’ll have dinner, then he switches it to breakfast, then cancels altogether. He’s told by M to use a specific gold bar to try and convince Goldfinger that Bond himself is dealing illicit gold, but instead, Bond decides to mess with Goldfinger in a game of golf where he discovers Auric is a cheater.

Many of these events match the novel, but in the book Bond’s first run-in with Goldfinger is happenstance, and he generally follows his orders a bit more closely. In the movie, with Sean Connery’s permanent half-smirk on his face, Bond’s mission seems to be basically to provoke Goldfinger as much as he possibly can, regardless of what his actual orders say he should be doing.

This strategy leads to a lot of collateral damage. Jill Masterson (Shirley Eaton) and her sister Tilly (Tania Mallet) are both killed, arguably, because of Bond’s intercession. Goldfinger’s personal pilot, Pussy Galore (Honor Blackman) certainly would have met this fate too; punished for helping Bond, but she’s inexplicably retained on Goldfinger’s payroll even after she overtly betrays him. In this way, Goldfinger brings to light one of the hidden quirks of Fleming’s books: Bond getting lucky isn’t a bug, it’s a feature. What gives Bond’s adventures a veneer of plausibility isn’t their physicality, it’s the fact that unlike a Sherlock Holmes figure or a superhero, Bond isn’t always making the right calls. And in Goldfinger, his mistakes, arguably, are what make the movie happen.

The Bond Palette Expands

While credited to Richard Maibaum and Paul Dehn, Goldfinger’s screenplay was greatly influenced by producers Harry Saltzman and Cubby Broccoli, as well as new director Guy Hamilton. Although Terreance Young had directed the first two Bond films, Hamilton replaced him for Goldfinger and immediately went to work putting his own stamp on the film. One of Hamilton’s biggest contributions was to make sure the movie was outside as much as possible. As chronicled in Paul Ducnan’s book The James Bond Archives, Hamilton stipulated that the film “ought to contain as many exteriors as possible so as to convince the audience we are there.”

While Dr. No and From Russia With Love are praised for their lush depictions of Jamaica and Istanbul, respectively, Goldfinger somehow feels even bigger. The most obvious example of the incredible feeling of the movie is the moody sequence in which Bond tracks Goldfinger on the winding roads of the Furka Pass in the Swiss Alps. Again, Bond behind the wheel of a car is part of why we remember this movie, making the fantasy both beautifully idyllic, but also relatable; we may not have a cool car like that, but who hasn’t imagined themselves silently tracking some other car on a secret mission?

The screenplay and direction of Goldfinger is also so tricky that we barely remember that in order for Bond to get his car to the Swiss Alps, it has to be flown there off-screen by some helpful chaps in the UK. (Goldfinger’s car is also loaded onto a plane to transport it.) This detail is hilarious and brilliant: In order to make a great car chase happen, the movie literally shows us that the cars—like toys being picked up by a child—have to be flown over to a different location so they can start driving around again.

Operation Grand Slam

Thinking about the finale of Goldfinger too hard will certainly cause you to conclude the movie is a nonsensical joke, so for the sake of your sanity, don’t think. Goldfinger’s plan to irradiate Fort Knox, and thus make the gold there less valuable and increase his own stock misunderstands the economics of the time and common sense in general. Plus, having Pussy Galore and her crew spray false poison gas is a ruse largely created for the audience, but makes little sense within the plot of the film.

But, as with all great Bond movies that would follow, you can’t care about these wonky details when you’re having this much fun. In addition to sporting a somewhat believable over-the-top villain in the form of Fröbe’s titular fiend, the film also introduces one of the best—if not the best—leading lady in any James Bond film. Blackman may have the most outrageous name of any Bond character, but her cred as an action star at the time was massive. Before joining Goldfinger, Blackman had been a co-lead with Patrick Macnee in the British TV spy series, The Avengers. (No Marvel connection at all.) This is the series in which John Steed (Macnee) had a hidden sword in his cane and partnered with a beautiful but deadly companion throughout the series. And while future Bond star Diana Rigg would become the more famous co-star as Mrs. Peele, it was Honor Blackman as Cathy Gale that gave the series its real style.

As in The Avengers, Blackman did a lot of her own stunts, and was a real-life brown belt in Judo. This means when she flipped Connery (and his stunt doubles) in the movie, she was doing those stunts for real. More than the two previous films, Blackman’s character changed the game for what women could and should be like in action movies. Pussy Galore may seem like a silly concept to someone who has never seen the movie, but within the context of Goldfinger, she is Bond’s equal, and in many ways, is the ultimate hero of the film.

An Entirely New James Bond Feeling

Watching Goldfinger back to back with its immediate predecessor, From Russia With Love, will lead to one startling revelation. Goldfinger feels like what we’ve come to expect of a Bond movie, and the two previous films are something else: quieter; more serious; vaguely plausible at times. Connery smiles a lot more in Goldfinger than he does in Dr. No and From Russia With Love, so much so that he seems more like a lad on vacation than a secret agent. This isn’t an insult of course, but if you were a Fleming purist, Goldfinger is certainly the moment where the tone of the films starts to depart from the reality-adjacent Cold War setting of the first two movies, which the series would only occasionally, and fitfully, return to a handful of times in the ensuing decades.

Bond is dangerous in Goldfinger, unquestionably. But in From Russia With Love, he’s smacking around allies and enemies without batting an eye. In Goldfinger, he’s batting his eyes at us. This is the movie where Sean Connery’s performance leans into the idea that some James Bond movies are big parties. In the movies that came before, we would sometimes witness long sequences of Bond checking into his hotels, changing clothes, and performing basic espionage work, such as checking a room for surveillance bugs. In Goldfinger, he’s wearing a white tuxedo underneath his wetsuit.

This tone pervades the entire film. Goldfinger rebooted James Bond in many ways, but the biggest change was that this time, 007 was having a lot more fun and he didn’t mind everybody knowing it.

Bond Becomes Self-Aware

As Sally Hibbin wrote in The Official James Bond Movie Book in 1987, Goldfinger was the moment in which the Bond franchise began to make fun of itself. “Filmmakers and audience conspire together in laughing at the film.” And although Connery was initially concerned about the copious amounts of humor in the movie, it’s impossible to imagine the franchise going any other way. Beginning with the opening sequence in which Bond electrocutes a would-be assassin and then says “shocking, positively shocking,” the recipe for the deadpan Bond pun was solidified right here.

But Bond isn’t the only one who gets all the laughs. This is the first film in which gadget-master Q (Desmond Llewelyn) is openly irritated with 007, and after dealing with an incredulous and unserious Bond, says “I never joke about my work, 007.” The trick, of course, is that the movie is kind of joking at this moment. Fleming did have an Aston Martin with a few tricks up its sleeve in the novel version of Goldfinger, but he certainly didn’t have an ejector seat. The cocktail of Bond-style excitement combined with a very specific brand of absurdism is what made Goldfinger a classic, and the film that all the other 007 movies—and countless other action movies—try to emulate to this day. But the movie’s balancing of these tones; deadly seriousness with raucous hyperbole is almost like a magic trick. Even 60 years later, it’s hard to really see how it’s done