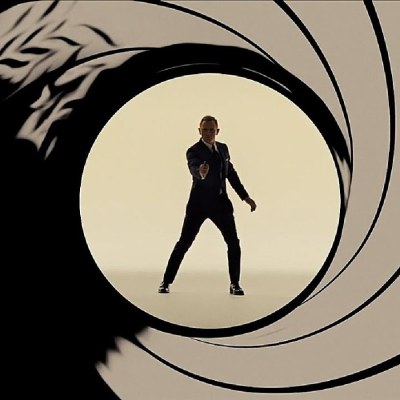

The Pleasure in Waiting Years for the Next James Bond

Three years after No Time to Die, and James Bond still hasn’t returned. There is satisfaction to be had in his absence.

Last week it was reported that Eon Productions is at last taking meetings with potential directors for the next James Bond movie—a film currently without a title or, for that matter, a Bond. British newspaper The Telegraph even broke the news with the faintly disapproving headline of “why it’s taking so long to find the next James Bond.”

It is indeed a surprise that almost three years after Daniel Craig’s interpretation of 007 took a final and fiery bow in No Time to Die, there still hasn’t been an heir apparent sized up for the tuxedo. Even before Craig’s Bond went out in a blaze of glory—all but demanding a reboot—members of the media and industry had already begun salivating at the idea of expanding the James Bond universe due to Amazon’s acquisition of MGM for $8.5 billion. Some predicted Amazon Prime TV shows based on the 007 intellectual property could be just around the corner, assuming of course the heads of Eon, siblings Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson, could be convinced to play ball.

Aye, there has been the rub about “updating” Bond for decades though. While a case could be made for James Bond being the first modern movie franchise, the rights to the character have remained solely with the Broccoli family since original Bond producer Cubby Broccoli bought out his partner Harry Saltzman in 1975. In other words, while the rest of the dominant media landscape’s “brands” and IP belong to major corporations who can mine a property for maximum profit, Bond remains essentially a family business.

The 007 series created an early recipe for how a character can exist in perpetuity on the big screen, and the Broccolis appear happy to keep making it just like how papa used to. If anything’s significantly changed, it’s that they have made the volume even rarer. Whereas in Cubby and Saltzman’s heyday, they were getting a Bond movie out every one or two years in the 1960s—and gradually more like every two or three years by the end of the ‘70s—under Barbara and Wilson the gap’s expanded to three, four, and even five years being normal. Increasingly, their 007 franchise resembles a bespoke, prestige label which is deliberately keeping its supply limited.

In the long run, and as someone whose stake in the Bond movies is based purely on my enjoyment of watching them, this has turned out to be the greatest of blessings.

Consider that one of the barely concealed secrets of the James Bond flicks is that until Craig got behind the wheel of an Aston Martin, there was virtually no continuity between installments, and many of the movies shared nearly identical plots. It might be a wonder even that Bond himself never seemed to clock that two years after meeting a megalomaniac who wanted to destroy the world and force everyone to live under the sea (1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me), he met another bloke with pretty much the same idea, except now he wanted to pick the survivors for his eugenics colony in space (1979’s Moonraker).

The plots, of course, were rarely the point. In fact, a great deal of the pleasure in watching a good James Bond movie is the sense of familiarity. Getting a proper Q scene, complete with a couple witty aspersions between Bond and the good quartermaster (preferably played by Desmond Llewelyn), followed by shots of exotic vacationing while “on the job,” and then the obligatory double entendres opposite women of equally relaxed virtue is all part and parcel with the package. The same way a theatergoer expects an overture when the curtain rises at the opera, Bond fans anticipate the car chase, the gadgets, and the megalomaniacal speech.

Even as the Craig era began by deliberately deconstructing or subverting these expectations in Casino Royale and Quantum of Solace, one of the joys in his later efforts, particularly the more popular installments, was how Eon brought back one by one the elements they’d stripped away in 2006. The ceremonial structure of the Bond movies is one of their most rewarding features—especially when you have gone years without attending this approximation of a vodka-soaked communion. Distance makes the heart grow fonder; it also makes what might otherwise be perceived as a limitation become a virtue. That’s refreshing to think about in 2024.

While the Bond franchise has staved off inquiries into “expanding” its universe on the small screen, so many younger but still fairly gray-haired franchises of yesteryear have given into the temptation of going supersized. Granted, it’s been a noticeable four and a half years since the last Star Wars movie, but that pause hasn’t been from a lack of trying on Lucasfilm’s part. The Disney subsidiary has failed to get a new movie set in that galaxy far, far away off the ground, but they have absolutely flooded the market with a glut of Star Wars TV shows for the streaming service Disney+.

When it started, that was a novelty too. Star Wars fans were over the moon about the first season of The Mandalorian being part of Disney+’s maiden voyage. They were ecstatic about The Mandalorian Season 2 as well. But a little less so for The Book of Boba Fett, despite that show also turning into a covert third season of Mando. The actual third season of Mando, meanwhile, came and went, as did the genuinely superb Andor. And nowadays, new Star Wars “content” that Disney could spend an eye-watering $180 million on, like The Acolyte, has become such a non-event to subscribers that Disney felt compelled to cancel the series.

Admittedly, there are a variety of other factors in the case study of Star Wars’ declining popularity, not least of which is the level of toxic online vitriol that has erupted from the angriest (and often most racist and sexist) corners of the fandom. Still, the phenomenon of Star Wars’ diminishing fan interest did not happen in a vacuum, and it did not happen because Disney dared center a new story on a woman. In fact, women led four of the five Disney-produced Star Wars movies in the 2010s, and all of those four crossed $1 billion. But the rapidity of their turnaround—where there was a new one every year—and the unevenness of their quality burned out audiences on what once felt like a true event.

Previously, the gap between Star Wars movies in this century ran the gamut of three to 10 years. But now there was a new one nearly every Christmas.

The over-saturation of the market has become a defining feature of the IP-crazed 2010s and 2020s, with studios producing so many films and/or series simultaneously that if something goes disastrously wrong—like, say, audiences flatly rejecting your dystopian vision of Batman and Superman becoming misanthropes—you’re stuck on the hook to take your lumps with the inevitable cascading failures of the next several years.

That phenomenon happened twice inside of a decade to the DC brand. First, there was the time when audiences rejected Justice League after the edgelord stuff proved a turnoff in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, as well as the widely watched but little liked Suicide Squad. The studio pivoted, awkwardly and unevenly. Even so, WB eventually realized the brand under at least its current form was losing audience interest after movies like The Suicide Squad (which was good, by the by) and Black Adam (which was not) flopped. By then, however, it was too late to not release four more back-to-back bombs in 2023.

Even the 21st century’s most popular movie franchise, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, has hit a point of diminishing returns, with audiences checking out of a few recent entries, and online fandom decrying the inconsistencies of Phases Four and Five. There definitely has been some inconsistency in the post-Avengers: Endgame MCU, too, but there were plenty of outliers in the earlier eras as well (remember Thor: The Dark World and The Incredible Hulk?). But back then, at the height of Marvel Studios’ popularity, they were producing two or three movies a year, not two or three movies a year and one Disney+ series in every fiscal quarter. The anticipation for the next Marvel movie has curdled into exhaustion with trying to keep up with all the D+ shows. That burnout even became comedy fodder in Marvel’s biggest hit in years, Deadpool & Wolverine.

“Welcome to the MCU,” Ryan Reynolds quips to Hugh Jackman. “You’re joining at a bit of a low point.” My audiences cackled because they seemed to agree. As did Disney. Hence the parent company promising investors they’re cutting the number of expected Disney+ Marvel shows in half.

At the end of the day, though, each of these other popular titles are beholden to shareholders and Wall Street, who continue to tinker at finding the maximum amount of content consumers will accept. By contrast, James Bond remains happily in the background, biding his time until you’re excited about the idea of seeing him again after a good long holiday.

With the exception of the last couple of Craig movies, the Bond franchise has never been director/auteur driven. It’s a formula that is closely guarded and refined by a family with a vested interest in its popularity. By keeping it scarce, they have also kept it special and frankly refreshing. Three years ago when Craig’s Bond was shockingly killed off, think pieces pondered whether he really needed to come back. But with the franchise about to pass the three-year minimum expected by a gap between 007 adventures, the headlines have transitioned dangerously close to “why haven’t they cast the next Bond yet?!”

By the time a new actor makes his debut, at least a half-decade will have gone by. Instead of mostly comparing the next guy to Craig, the barometer is going to be how does he make that formula his own while giving us the beats and scenes we’ve come to miss? To paraphrase a Soviet assassin once played by Famke Janssen, “This time, Mr. Bond, the pleasure will be all ours.”