How 1974 Became the Year of the Disaster Movie

How Airport 1975, Earthquake & The Towering Inferno got made in what turned into a seminal year for disaster movies...

Back in the mid-70s, big budget, effects-laden disaster movies reigned supreme. 1974 saw three giants of the genre go head-to-head – but it wasn’t all plain sailing as each raced to cash in on the new taste for terror.

Way back in the 70s, long before the likes of Geostorm, San Andreas, and 2012, disaster movies were enjoying a golden age. While these movies may have lacked the global scale of the modern disaster film, in their own way they created more immediate, intimate – and perhaps more unsettling – scenarios that audiences could relate to: the plane engine blowing, the cruise liner listing heavily, the tower block stairway filled with smoke and fire.

Of course, these weren’t meant to be gritty, realistic films. The stars always survived – but would you? These were situations anyone could find themselves in, and that gives the films a troubling edge beyond the hokey one-liners, clunky exposition and acts of (usually) pointless heroism.

In their heyday, every studio wanted a share of the disaster pie: hundreds of millions of dollars were spent blowing up, burning down and otherwise destroying large, normally indestructible objects.

And so it came to pass that lucky (or intrepid) audiences could look forward to not one, not two but three disaster blockbusters in the last few months of 1974: Airport 1975, Earthquake, and The Towering Inferno.

Each had big budgets, bigger stars and cutting edge special effects, but which would win the battle of the box office?

Airport takes off

Although hit disaster movies are as old as Hollywood itself – San Francisco, the story of the 1906 quake starring Clark Gable, Jeanette McDonald, and Spencer Tracy was the top grossing movie of 1936 – it was only with Airport in 1970 that they began to break records.

There had been other successful airborne disaster films before, most notably No Highway In The Sky (1951), The High And The Mighty (1954, with John Wayne), and Zero Hour! in 1957, but it wasn’t until Airport’s combination of lavish production values and big names (in this case Burt Lancaster, Dean Martin, George Kennedy and “a cast of stars as long as a jet runway”, according to Variety) that its studio, Universal, had a bona fide hit on its hands.

No matter that the critics were largely unimpressed – even Lancaster himself described the film as “the biggest piece of junk ever made” – Airport was brash, confident and hugely successful: a budget of $10 million earned $100 million at the box office. It also garnered an impressive number of Oscar nominations: 10 in all, including cinematography, adapted screen play, score, costume and two supporting actress nods.

As the new decade opened, Airport’s success showed that these big films could be big business. Every Hollywood studio was realising the potential of disaster to reap rich rewards, and looking for the next scenario in which disaster might strike.

The big one?

On the morning of Tuesday, February 9th, 1971, Californians were waking up to a normal working day like any other.

With sunrise still an hour away, many were still asleep when, at 06:00 precisely a 6.6 magnitude earthquake struck the San Fernando Valley in northern Los Angeles. Although bigger quakes had hit before, this one caused unprecedented destruction to LA’s urban and suburban areas: hundreds of buildings were destroyed, sidewalks were lifted several feet into the air, freeway overpasses collapsed and – most devastating of all – two large hospitals suffered almost complete disintegration and many fatalities. The huge Van Norman dam was severely damaged and came close to total failure; luckily it held – more than 100,000 people lived downstream.

For millions of traumatised Angelenos, this latest quake was too close for comfort. But for Jennings Lang, it was a godsend.

Lang was a well-known and well-respected producer working for Universal, the studio behind Airport. Like many in Hollywood, Lang had risen through the ranks from the bottom up, starting out in casting after leaving behind a career in law in 1930s New York. Within a few years he was running his own talent agency before moving again, this time into production. His career had not been without perquisite colour, however: at one point in the 1950s he’d been shot in the leg by a fellow producer convinced that Lang was having an affair with his actress wife.

Something of a larger-than-life character, and ever the showman, in 1971 Lang had ambitions to replicate Airport’s success with a film of his own, only this time bigger and better. Casting about for inspiration, he found it in the San Fernando disaster.

The film rumbled into development, called simply Earthquake. As executive producer, Lang’s first task was to assemble his talent. Bringing legendary director Mark Robson on board to produce and direct was an excellent choice: in his long and varied career Robson had worked with the likes of Orson Welles and Val Lewton editing and directing more than 40 films; his were a safe and trusted pair of hands. All Lang needed was a decent writer to bring Earthquake to life – and quickly, before others had the same idea.

His luck was in. Early in 1972 he secured the writing services of Mario Puzo, fresh from success as author of both the novel and screenplay of The Godfather. Released in March 1972, The Godfather was currently garnering the acclaim most films could only dream of, and would go on to become one of the most beloved and highly rated films of all time. For Lang and his pet project it was a very promising start.

By late summer Puzo had penned a first draft of Earthquake. Even at this early stage it was full of complex, fully-fleshed characters and action scenes set throughout LA. As he read it over, Lang realised Puzo’s script as written was going to need a much bigger budget than the $7 million Universal had agreed for the film. He was faced with an unenviable choice: convince Universal to increase the budget, or persuade Puzo to cut the script down to a more manageable size.

It was a quandary solved by Puzo himself. Over on Melrose Avenue, Paramount was keen to begin work on the sequel to The Godfather, also due for release in 1974. Puzo, contractually obliged to deliver a script for it, felt he couldn’t commit to two equally massive productions, and took the decision to walk away from Earthquake.

(Now, like me, part of you is probably imagining how a Puzo-penned Earthquake might have panned out, and it’s true it’s a intriguing prospect. But if he’d stayed to write it, we’d have missed out on the best sequel ever made, so we mustn’t complain.)

Reluctantly – and to Lang’s frustration – without a writer on board to manoeuvre the script into a more manageable position, Universal took the decision late in 1972 to wind down production on Earthquake.

Poseidon rules the waves

Like Jennings Lang, Irwin Allen was a colourful figure in the film production world. Having left New York for LA after the Great Depression, just as Lang did, Allen worked his way into film via journalism and radio. He had spent the 50s producing largely forgettable films for 20th Century Fox, but when Fox got its fingers burned with the lavish (but ruinously expensive) Cleopatra, Allen’s ambitions were scaled down to the more cost-effective world of television.

Less risky, and cheaper, his productions nonetheless had a massive impact on the cultural psyche: he created the original TV series of science fiction classics Lost In Space, The Time Tunnel, Voyage To The Bottom Of The Sea, and Land Of The Giants.

Allen might have stuck with this sci-fi genre had he not come across a 1969 novel about a cruise liner that capsizes after being struck by a tsunami, trapping its passengers in its upturned hull. With the same canny instinct that had buoyed his seminal TV career, Allen knew he was onto something spectacular, and immediately bought the film rights.

At first Fox agreed to foot the nearly $5 million budget for the film Allen was proposing, but just as filming was about to start they pulled the money. Their fear was that audiences were turning to more nuanced, cynical and realistic fare: after all, as well as The Godfather, the early seventies would see Easy Rider, The Graduate, Bullitt, Deliverance, The French Connection, Dirty Harry, and Straw Dogs usher in another era of classic American films.

Indefatigable, Irwin refused to give up on his vision of a high-budget all-star action spectacular. Over lunch at his country club, and with his trademark charm, he managed to raise half the money needed from a couple of (very wealthy) friends. Fox bought back in with the other half, and filming on The Poseidon Adventure began.

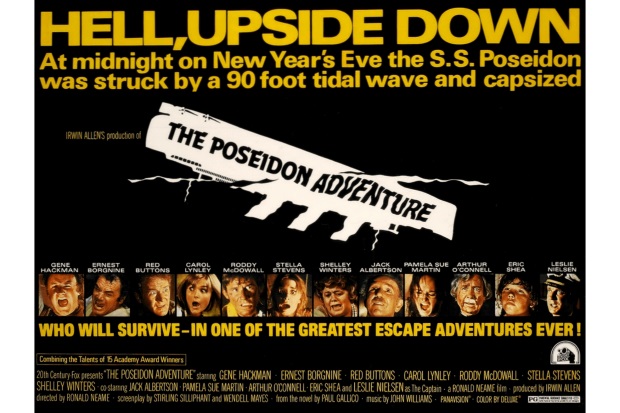

With a seasoned ensemble cast including Gene Hackman – fresh from Oscar success with The French Connection – Ernest Borgnine, Jack Albertson and Shelley Winters, a John Williams score and a screenplay by Oscar-winning Stirling Silliphant (surely the best name of anyone in Hollywood, ever), The Poseidon Adventure remains an unsettling film even if most of its characters don’t go beyond two dimensions. It creates a convincing, nightmarish scenario in which the passengers’ world is literally turned upside down, and where there’s a high cost to be paid for the smallest of wrong decisions.

Racking up nine Oscar nominations, including Shelley Winters for best supporting actress, cinematography, editing, sound, song (which it won) and Williams’ score, the film was another unqualified success, eventually taking $123 million at the box office (only The Godfather earned more that year). Significantly, special achievement Oscars were also awarded for the film’s groundbreaking visual effects, created by LB Abbott and AD Flowers.

Irwin Allen’s vision of a spectacular event movie had paid off. Riding high on his film’s record-breaking takings he decided to leave his sci-fi days behind and commit himself to only making disaster movies. Like Lang before him, he too began to look around for new ideas.

Towering ambitions

In 1973, Allen stumbled across Richard Martin Stern’s novel The Tower, inspired by the completion that year of the World Trade Center’s 110-story Twin Towers in New York – the tallest in the world at the time.

Stern’s fictional World Tower Building is fatally compromised when contractors cut corners during its construction. A disgruntled sheet metal worker decides to set off a bomb in the basement and, in the ensuing conflagration, the survival of the Tower’s occupants depend (among other things) on a life line thrown across to the nearby World Trade Center.

Something of a pot boiler – but a hugely popular one – it seemed to Allen ideal material to be adapted into a film. But he was not the only one to recognise its potential: to his disappointment the rights were snapped up not by Fox, but by Warner Brothers for a cool $400,000.

Unsurprisingly, Allen was not one to give up so easily. Early in 1974 another novel about a skyscraper blaze was published, The Glass Inferno by Thomas Scortia and Frank Robinson. In a plot similar to that of The Tower, the eponymous building is built to minimum safety compliance; this time the occupants are only saved from certain death by the rupturing of giant rooftop water storage tanks. Second time around, Fox was successful in securing the rights.

It looked as if 1974 was destined to see two blockbusters with almost identical premises and plots in production at the same time. Although not the first – or last – time competing films have been scheduled together, both Fox and Warner Brothers realised that the situation would almost inevitably dilute the impact of both movies.

In a Hollywood first, the rival studios decided to pool resources and work together in a co-production. Both committed half of the massive $14 million budget – a canny decision which would allow the movie the luxury of two ordinary films’ worth of investment to play with. In return, the US box office would go to Fox and the foreign market receipts to Warner Brothers.

Eventually titled The Towering Inferno, and with Poseidon’s Stirling Silliphant corralling the best elements of each novel into a workable script, both studios hoped this unprecedented gamble would result in a film to rival both Airport and Poseidon.

Earthquake resurrected

Over at Universal, Poseidon’s enviable box office performance also reignited the Earthquake production, which had languished since Puzo left the project.

It was clear that the disaster genre still had many miles to run, and Lang believed that a reinvigorated Earthquake could prove a serious rival to the Fox/Warner Brothers Inferno, even with less than half their budget. Better still, if he could get the film into the cinemas ahead of Inferno, he might steal some of their thunder. Production immediately moved into a high gear. A replacement writer was signed up to the project – although as a magazine copywriter, George Fox had no experience of screenplays. But veteran director Mark Robson was on hand to help him condense Puzo’s sprawling first draft into a tighter, leaner script.

After 11 more drafts, principal photography began in February 1974, with Charlton Heston, Ava Gardner, George Kennedy, Fred Astaire and a whole host of other stars in front of the cameras.

Earthquake was not the only Universal disaster movie Charlton Heston, George Kennedy – and Jennings Lang – were involved with that summer. Not to be outdone by the other studios, and eager to cash in on a proven smash hit, a sequel to Airport was also being developed alongside Earthquake.

Determined to do things bigger and better than the original, Airport 1975 is set aboard the iconic Boeing 747 jumbo jet, the biggest and newest passenger aircraft at the time.

George Kennedy’s character from Airport, Joe Patroni, returns, now Vice President of Operations for fictional Columbia Airlines – not a bad promotion from lowly mechanic in the first film a few years previously. Charlton Heston is Captain Al Murdock, Columbia’s Chief Flight Instructor tasked with bringing Flight 409 down safely after a mid-air collision with a light aircraft. At the controls of the stricken flight is senior flight stewardess Nancy Pryor (Karen Black), Murdock’s girlfriend. With the captain of the flight unconscious and the plane unable to turn in autopilot mode, Murdock must talk Pryor through navigating the peaks of the Wasatch Mountains over the plane’s radio.

Aside from the serviceable plot, it’s the passengers who are the most memorable thing about the film: Gloria Swanson in her final acting role, playing herself as fading movie star and providing her own dialogue (both Greta Garbo and Joan Crawford had been offered, and turned down, the role); Helen Reddy as singing nun Sister Ruth, bringing out her guitar to perform Reddy’s own song Best Friend from her debut album (a bit like Harry Styles breaking into Sign Of The Times mid-Dunkirk); Linda Blair – whom audiences had seen in a very different role in The Exorcist only a few months before – as Janice Abbott, a sick child travelling to undergo an organ transplant. Others include Myrna Loy as an alcoholic, Sid Caesar as a small time movie actor and Erik Estrada as a flight engineer.

Initially Heston had been reluctant to sign up to the film, having only recently played the captain of a passenger jet in another thriller, Skyjacked, in 1972. But he was finally persuaded and, such was the rush to wrap the film in time to compete in that year’s box office, Heston had only 15 hours between finishing work on Earthquake and filming his first scenes for Airport 1975.

The competition heats up

In May 1974, as Airport 1975 was filming, The Towering Inferno, now with Steve McQueen, Paul Newman, William Holden and Faye Dunaway in the lead roles, began shooting.

Signing up two of the biggest names in Hollywood may have had Fox and Warner Brothers salivating with anticipation – Steve McQueen was the highest paid actor in the world at the time – but the infamous rivalry between McQueen and Paul Newman caused friction from the outset.

McQueen had turned down a role in 1969’s Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid because of disagreements over top billing with Newman, and the same conflict surfaced on Inferno too.

Neither actor would agree to be second-billed, so the studios came up with an innovative solution: their two names were spelt out diagonally on screen and posters, so that both actors would appear first – depending on whether you read top to bottom or left to right.

To avoid more wrangling, both stars were offered the same pay – $1 million, and 7.5% of box office – and the same number of lines. McQueen, keen to upstage Newman, insisted on playing fire chief Mike O’Halloran, who doesn’t appear in the film for a good 40 minutes, ensuring that by the time he was on screen opposite Newman, the latter had already used up most of his lines, and would not dominate their scenes. To his credit, Newman (playing architect Doug Roberts), was far more relaxed about the whole thing – unlike his co-star, who insisted he be left undisturbed by unwanted visitors and crew while on set.

Nor was it plain sailing with the other members of the cast. Faye Dunaway was notorious for being late on set, some days not turning up at all – to the exasperation of more seasoned actors, especially William Holden (already aggrieved he’d not been given top billing, being told he was not the box office draw he’d once been). At one stage Holden was so infuriated at Dunaway’s persistent lateness that he angrily pinned her to the wall. Unsurprisingly, she was on time for the rest of the shoot.

Innovative effects

Both Airport and Poseidon had shown that one ingredient was vital if a disaster film was to deliver: top notch special effects.

For Inferno, this was a massive technical challenge. The action centres on a 138-storey gold and glass behemoth of a skyscraper that must first burn and then get drenched with a deluge of water. Obviously, none of this could be filmed on a real building, so the shoot would inevitably involve miniatures – but fire and water are notoriously difficult to ‘miniaturise’: get them wrong, and their speed and behaviour instantly betrays the real scale of the set.

It was decided to bring back the duo who’d won the visual effects Oscar for Poseidon, LB Abbott and AD Flowers. After lots of experimentation, construction finally began on a scale model of the tower – though at 70 feet high there was nothing small about it (that’s about the height of a 5-story building).

For the flames themselves, any kind of liquid fuel would have been too dangerous to work with, so a custom mix of gases was used instead. Butane burns with a blue flame and little smoke, while acetylene gives an orange flame and lots of black smoke – by mixing different amounts of each gas, the pyrotechnists were able to create exactly the right look for each shot. Along with these flammable gases, compressed air was pumped in to agitate the flames, with an ignitor to spark the whole thing to life.

Despite best efforts to ensure safety of the crew, the shoot was fraught with danger. On one occasion, there was a 10 second delay in the ignitor sparking, allowing a huge amount of gas to build up before lighting; the ensuing explosion was so massive it sent debris and glass flying everywhere – and so spectacular the shot was used in the film.

Five floors of the tower were also constructed full scale, including the 135th floor Promenade Deck, where a large number of people become trapped as the flames take hold. Surrounding it was a 340-foot cyclorama of the San Francisco skyline, painted in such painstaking detail that even the shimmer of moonlight on the far off sea was simulated by cutting curved slits in the backdrop, lighting strips of silk hung behind it, and fluttering them with a fan to make them shimmer. This set alone cost $300,000 to build – and was then totally destroyed by thousands of gallons of water for the film’s climax.

In all, 57 sets were constructed on the Fox backlot for Inferno, the highest number for a film at that date, with a record 4 camera crews covering the action.Irwin Allen directed the action sequences himself, and did a very decent job. No wonder he was beginning to earn himself the nickname ‘Master of Disaster’.

Not to be outdone, Universal were busy putting everything into the effects for Earthquake, even though the film’s budget was half that of Inferno. Glen Robinson (who’d begun his film career in the props department of The Wizard Of Oz) was the man in charge of constructing the vast numbers of buildings and landscapes that would be destroyed by the catastrophic seismic event.

Full scale sets were created on roller systems that moved and tilted as the action required, all filmed by cameras with specially-designed ‘shaker mounts’ beneath them. Most spectacularly, a 50-foot model of a dam was built and then destroyed. Earthquake set the record for the most stuntmen employed on a production: 141 in total. Inevitably, there were accidents; several stuntmen were injured filming the elevator crash scene, and one unfortunate man suffered concussion when debris fell on him during the flood sequence – again, resulting in footage that was too good to not include in the final film.

To augment the live action, matte paintings were created by artist Albert Whitlock, rightly considered one of the greatest of Hollywood’s old school matte painters. He produced 22 panoramas for use in 40 scenes utilising his special ‘impressionistic’ technique: up close the paintings look less real than a photograph, but when shot on film they appear more convincing to the eye than a hyperreal depiction.

But Earthquake’s biggest technological innovation was its use of sound. To make this a truly spectacular event movie, Jennings Lang wanted to the earth to move for the viewer – literally. What if the audience could feel, as well as see and hear, the tremors on screen?

An initial idea of dropping styrofoam debris on the audience at appropriate moments was quickly (and unsurprisingly) abandoned for something far more realistic: Sensurround, a system of sub-audible vibrations transmitted through specially-installed speakers. Cues on the soundtrack triggered these infrasounds – sound waves which, at less than 20hz, can’t be heard by the human ear but can be felt in the body as vibrations. Experienced by the audience as subsonic rumblings, it felt as if real tremors were shaking the auditorium beneath their feet.

It was a huge undertaking. Not only did the technology have to be invented – including the now-ubiquitous subwoofer speaker and ultra high capacity amplifiers – but sets of the massive speakers had to follow the film prints around the world in the weeks prior to it opening. For the individual theatre, the cost of showing the film was substantial: $2,000 for speaker installation, plus $500 a week rental for the duration of the run.

Unsurprisingly, Universal played Sensurround for all it was worth – perhaps to convince the theatre managers as much as anyone in the audience. Promotional literature assumed “no responsibility for the physical or emotional reactions of the individual viewer”; for a premiere at the iconic Grauman’s Chinese Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard, a huge net was placed beneath the ornate plaster ceiling in case the vibrations caused it to disintegrate. Just as Lang had hoped, these gimmicks were hugely successful in creating a buzz around the film ahead of its release.

Post production wobbles

By late Autumn, production on all three films was nearing completion. With release dates set for the last three months of 1974, none could afford to slip up schedule-wise. But Earthquake had one final hurdle to clear.

After less than impressive reaction to test screenings across America in October, a decision was made to cut 30 minutes of footage from the film, with fairly major implications for the narrative of the story. Most cuts were intended to slim down the bloated character set-up – most notably, a backstory involving abortion and attempted suicide that had explained the conflict in Heston and Gardner’s marriage. Other parts of the film – deemed too graphic for a PG rating – were toned down. The biggest casualty of this tweaking was a scene where loss of power causes an elevator full of people to plunge dramatically to the ground. Just to make sure the gruesome implications were sufficiently glossed over, some (literally) cartoon blood was spurted onto the camera at the moment of impact.

With changes to Earthquake finally in the bag, all three films were ready for release. Entering the home straight, all three hoped they would dominate as the year came to a close.

And the winner is…

First out of the gates was Airport 1975, on October 18th. Most critics were disappointed, dismissing it (as the New York Times did) as a “silly sequel” with a “total lack of awareness of how comic it is when it’s attempting to be most serious”. A few thought it better than the original, notably Roger Ebert, who singled out the plausible special effects for praise – though he did question whether a highly trained senior stewardess would really prove so clueless in an emergency. Which is a good point.

Grossing a healthy if under-par $47 million at the box office, it came in 7th on the list of top-performing films of the year. Far below the nine-figure returns of Airport, it was nonetheless enough to secure two more sequels over the next few years: Airport ’77 and The Concorde… Airport ’79.

Earthquake opened in mid-November, and the reviews weren’t much better. Although describing it as a “hackneyed disaster epic”, Pauline Kael could find some room for generosity: “The picture is swill, but it isn’t a cheat; it is an entertaining marathon of Grade-A destruction effects.” And for all its silliness and implausible plotlines, Earthquake took a more than respectable $80 million in box office receipts, an extremely decent return on an original budget of $7 million and one that saw the film take fifth spot in the best ranking movies of the year.

The last of the three films to be released, Inferno, was really the only one to perform as hoped, both in terms of box office and critical opinion. In Roger Ebert’s opinion it was “the best of the mid-70s disaster films”. It was the only one of the three to pass the $100 million mark, taking it to the number one spot for 1974 with a grand total of $116 million in domestic receipts. The unlikely co-production gamble taken by Fox and Warner brothers had paid off handsomely.

And awards? Well, with the 1975 awards season dominated by new-wave juggernauts The Godfather Part II and Chinatown, it’s perhaps not surprising that Airport 1975, relatively unloved by audience and critics alike, went largely unnoticed. It secured just one nomination – for Helen Reddy, as the Golden Globes’ most promising newcomer.

On the other hand, Earthquake and Inferno did very well, being nominated for 4 and 8 Oscars respectively. These were mostly in the technical categories; both films were nominated for editing, cinematography, sound and art direction. And, in a year in which John Williams was kept very busy (scoring both Inferno and Earthquake, as well as films for Steven Spielberg and Martin Ritt), Inferno was also nominated for best score. Not quite the 10 Academy nods of Airport, but not far off.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, Earthquake won the Oscar for its innovative sound design, and also bagged special achievement Oscars for its two purveyors of special effects, Glen Robinson and matte painter Albert Whitlock. Sensurround itself was destined to be a short-lived phenomenon. It was used in just three more films – a 1976 remake of King Kong, Midway (1976), and Rollercoaster (1977) – as well as for the theatrical released of the 1978 Battlestar Galactica TV pilot. But by the end of the seventies theatres were inevitably falling into the orbit of Lucasfilm’s THX and DolbyStereo, both of which would prove far more enduring than Sensurround.

Inferno did the best in converting Oscar nominations to wins. It won three in total, for editing, cinematography and best song. Props are also due to the Academy for nominating septuagenarian Fred Astaire as best supporting actor for Inferno, in a category dominated by three performances from The Godfather Part II.

Perhaps the most satisfying vindication for the Fox/Warner Brothers’ collaboration (and a personal victory for Irwin Allen, whose name was on the nomination) was Inferno’s entry in the best picture category. But in a year when its competition was The Godfather Part II, Chinatown, and The Conversation, it was not to be. As in so many other categories that night, The Godfather Part II swept all before it.

Death knell for disaster

By the end of the seventies, it was clear that big disaster films had had their moment in the sun. 20th Century Fox’s earlier reluctance to fund films like The Poseidon Adventure and The Towering Inferno looked increasingly prescient as the years wore on – though even as far back as 1970 Airport had been described as “bland entertainment of the old school” by Pauline Kael and “a bygone brand of filmmaking” by Variety. Chinatown, The Godfather Part II, Apocalypse Now, The Deer Hunter – by the end of the decade, these were the new gold standards of American film.

And even if you weren’t looking for such highbrow fare, the explosion of culture-changing films from Messrs. Lucas and Spielberg were, by that time, changing the face of cinema forever. Master of Disaster Irwin Allen, who’d done so much to breath life into the genre, couldn’t understand the appeal of these newfangled films. Their success bewildered him. How could Star Wars be so all-encompassing when it featured no big name stars? How could Close Encounters Of The Third Kind or Jaws be such massive hits without an obvious love story attached to them?

Allen, committed as ever to old-school all-star epics, would end his lucrative association with Fox when the studio decided to cancel a trio of scheduled disaster films. At – ironically enough – Warner Brothers, he would attempt to breathe life back into the genre with made-for-TV films full of exclamation points – including Flood! (1976), Fire! (1977) and Cave-In! (1983). He also produced and directed lacklustre offerings The Swarm (1978) and Beyond The Poseidon Adventure (1979), before moving into more family-oriented fare until his retirement in the mid-eighties.

Following Airport 1975, Jennings Lang would go on to produce both future Airport sequels, as well as Rollercoaster (1977), but in the ’80s he would turn to comedy dramas. Like Allen, his career never again hit the heady heights of 1974: his sequel to The Sting in 1983 has the unenviable accolade of scoring 0% on Rotten Tomatoes.

Even though Airport 1975 lost the battle of the 1974 box office, of the three films it had perhaps the happiest (if unintentional) consequence for cinemagoers, and one that would spell the end for the disaster genre: the parody film.

Airplane! (1980) took the wind out of the overblown, over-earnest disaster genre’s sails more effectively than any box office failure – by lampooning it. Although actually a riff on the earlier Zero Hour!, it features many recognisable elements from Airport 1975: the nun, the sick child being sung to, the stewardess at the controls and so on. It’s hard not to feel sorry for the Airport franchise in the light of Airplane!’s brilliance and longevity, but perhaps it’s a mark of the original’s presence that it was deemed so worthy of pastiche.

The disaster boom of the seventies officially died, then, in 1980. This was the year Steve McQueen – who had taken a four-year break from acting after his involvement with Inferno – turned down a role in a proposed Inferno sequel, and died not long after. It was also the year the last gasp of the Airport franchise, The Concorde… Airport 1979, earned risible reviews – and ignominiously failed to earn back its budget.

But most memorably, and perhaps most fittingly, 1980 was the year that Leslie Nielsen – with a little help from an inflatable autopilot – officially brought the genre back down to earth.