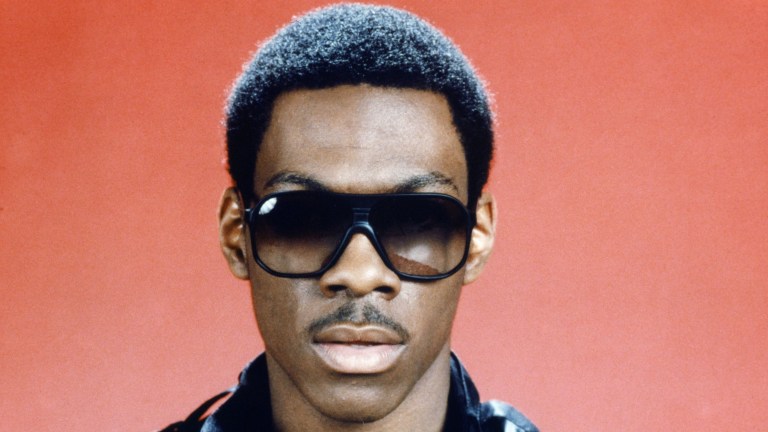

The 48 Hrs. Scene That Made Eddie Murphy a Movie Star

Before becoming the biggest movie star of the 1980s, Eddie Murphy was a young man overwhelmed on the set of 48 Hrs... until he got to a controversial scene.

Things were going badly on Saturday Night Live‘s 1980-1981 season, even before producer Jean Doumanian realized than the January 10, 1981 episode was headed towards disaster.

The previous season had seen the departure of Lorne Michaels and the entire cast, including founders Gilda Radner, Jane Curtin, Garrett Morris, and Laraine Newman, as well as Bill Murray and Harry Shearer. Doumanian had tried to pitch her incoming group of comedians as the next generation for the hit series, but the performers quickly gained reputations as also-rans. Charlie Rocket was a less funny Chevy Chase, Gail Matthius an off-brand Jane Curtin, and so on.

But on that Jan. 10, 1981 episode, hosted by actor Ray Sharkey, things were going particularly badly. The skits went faster than anticipated and the show had five extra minutes to fill. So in an act of desperation, Doumanian followed the advice of writer Neil Levy and pushed 19-year-old featured player Eddie Murphy onto the stage to do some stand-up.

Murphy killed it. He graduated to main player two weeks later, a spot he held even after the rest of the new cast (save Joe Piscopo) were fired. The rest is history, right? Well, not quite. That same year, it took a similar act of desperation to turn Murphy from a TV star to a movie star.

The Clock is Ticking on 48 Hrs.

To solve a case in forty-eight hours, a tough cop needs the help of a hardened criminal. That’s the simple premise that producer Lawrence Gordon came up with for a movie that he pitched to action director Walter Hill, as the duo were making the Charles Bronson and James Coburn two-hander Hard Times. As the idea bounced around between writers, directors, and studios, it eventually became a Clint Eastwood vehicle called Loan Out. “But he didn’t want to be a cop,” Hill told author Nick de Semlyen in the book Wild and Crazy Guys. “He already had the Dirty Harry franchise.”

The project finally landed at Paramount Pictures, which had Nick Nolte under contract for one more movie, with Hill as the director of the project. Now called 48 Hrs., the project starred Nolte as San Francisco Inspector Jack Cates on the trail of violent escaped criminals Albert Ganz (James Remar) and Billy Bear (Sonny Landham). Desperate to stop the duo’s violent rampage, Cates checks out from prison Ganz’s former associate, a fast-talking criminal, first called Willie Biggs in the script.

Hill originally wanted Richard Pryor for the role and then Gregory Hines for the criminal role, hoping that he could make for a more improv-heavy movie with plenty of chemistry between the leads. But Hill’s girlfriend at the time, an agent named Hildy Gottlieb, had a client she wanted him to check out. Hill saw the value in Murphy, but worried about giving such a fresh actor a part this big. According to Semlyen’s book, Hill expected that his main star would have to make up for Murphy’s shortcomings as a much greener performer.

“It’s going to be like acting with a kid or a dog,” Hill told Nolte before shooting began. “You’ve got to be good every take, because the one take he’s great, that’s the one we’re going to print.”

Much to his own chagrin, Hill was right. At first.

Setting Torchy’s on Fire

Eddie Murphy had no energy. That was the way Paramount felt when they watched the dailies from 48 Hrs. In place of the electric guy they saw on television, they saw a fine, but unremarkable, young actor lagging behind Nolte.

Paramount wanted to fire Murphy, but Hill stuck with him, trying to find the secret to unlocking the talented performer. He accepted Murphy’s suggestions to change the name Willie Biggs to Reggie Hammond, and even brought in screenwriter Larry Gross to write new material, better suited to the strengths of the stars. That writing addition pointed the way.

“We came to the conclusion that Eddie was best whenever he was competing with Nick over something in the scene,” Gross told Semlyen. “That activated some nerve center in him and suddenly he’d come alive and be mesmerizing. So we had to work up moments that were like a jump ball in basketball, with two guys going for the ball.”

Gross and Hill found the ultimate stage for competition in an early scene. Originally, the script featured a moment in which Hammond brings Cates into a bar filled with Black patrons, giving the younger man a chance to tell his older colleague how it’s done (a variation of which does exist in the finished film).

But Gross and Hill rewrote the scene so that the bar was reimagined as a redneck joint called Torchy’s. Now, Hammond would be on enemy ground, which suited Murphy just fine. Walking onto a set filled with Confederate flags, aware of the disappointment with his performance so far, Murphy took control.

The scene begins with Murphy playing Hammond as one of his easy-to-get-along-with freewheeling characters, a guy who talks friendly to the bartender (character actor Peter Jason) and gives the sneering white man a chance. But when the bartender refuses to cooperate, Hammond switches modes.

Wielding Cates’ badge and pretending to be a police officer, Hammond shatters the mirror behind the bar with his glass and begins strutting across the floor, giving the cowboy hat-wearing patrons a mean, cold look. For a second, Murphy lets a bit of fear creep into the corner of Hammond’s eyes when he realizes that he’s surrounded by big rednecks, but then the criminal channels the power-tripping officers he’s met a million times before. “Never seen so many backward-ass country fucks in my life,” he declares, swaggering up to a regular.

The scene was exactly what Murphy needed, a chance to show everyone what he had, a chance to be dangerous, unpredictable, and raw. When one of the patrons asks Hammond what kind of cop he is, Murphy delivers a line that still raises the hair on viewers’ necks today: “I’m your worst fuckin’ nightmare man. I’m a n____er with a badge, that means I’ve got permission to kick your fucking ass whenever I feel like it.”

“We’re rich,” Hill allegedly told Gross after watching Murphy go.

Can Eddie Murphy’s Fire Rage Again?

Hill was right. Although Paramount threatened to cut the Torchy’s scene down to something less offensive, the movie was released with Murphy’s performance intact. 48 Hrs. grossed $78.9 million on a $12 million budget, launching Murphy to super-stardom.

The Torchy’s sequence captures a key aspect of Murphy’s humor, something present in his early electric performances and too often missing from movies such as Tower Heist or A Thousand Words. By taking the position of a Black person hassled by police and using their tactics against white people who benefit from that abuse, Murphy uses Hammond to disrupt the very tension at the heart of the cop movie.

Yes, viewers want him and Cates to stop the brutal Ganz and Billy Bear, but no one is necessarily pulling for Nolte’s thug of a detective. When Hammond takes control in Torchy’s, it’s not just Murphy using his considerable charisma and talent, burning with something to prove. It’s a necessary corrective to what is already becoming an era of slick cop movies about police officers who do whatever they want. While pretending to be a cop, Hammond strips the power away from the police, inviting audiences to guffaw at them as nothing more than bullies.

Although Murphy has been good in recent years, especially in the Rudy Ray Moore biopic Dolemite Is My Name, we haven’t seen the dangerous Murphy in a long time. Things haven’t gone Murphy’s way for decades. But as his breakout demonstrated, Murphy is most electric with the odds stacked against him.