Please Don’t Turn The Matrix into a Shared Universe

There is a new Matrix movie coming without a Wachowski sister in the director’s chair. It feels like we’ve been here before.

A case can be made that Drew Goddard is one of the more underappreciated genre voices to break through in the last 20 years. The filmmaker has had an impressive track record, from writing and directing a bonafide cult classic like Cabin in the Woods to also penning one of the best sci-fi movies of this century, 2015’s The Martian, which was adapted from the Andy Weir novel of the same name and earned Goddard an Oscar nomination. He also wrote the original Cloverfield and helmed the extremely overlooked Bad Times at the El Royale. In nerd circles, his name should be revered.

Even with that esteem though, we cannot ignore that a vast shadow of trepidation descended Wednesday afternoon when the news hit: Goddard has been tapped to write and direct what will be a fifth and currently untitled Matrix film—a first for a series which up until now has never returned to the big screen without at least one Wachowski sister in the director’s chair.

The details of the project are currently scarce beyond Goddard’s involvement, although Warner Bros. Pictures’ press release stressed that Lana Wachowski has been retained on the project as an “executive producer.” Similarly, both WB executives and Goddard himself speak glowingly about the influence the Wachowskis’ work have had on cinema and the studio.

“It is not hyperbole to say The Matrix films changed both cinema and my life,” Goddard said in the statement. “Lana and Lilly’s exquisite artistry inspires me on a daily basis, and I am beyond grateful for the chance to tell stories in their world.”

Stories? More than one?! There’s that reflexive shudder again.

While the release indicates Goddard came to WB with a pitch for another Matrix film set within this world, one cannot help but initially speculate whether the studio had put out feelers for pitches, especially after Warner Bros. Discovery CEO David Zaslav lamented to investors last year that the studio’s “great IP” like Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings were “underused,” and that the studio hadn’t “done anything with [them] for more than a decade.” In reality, it had been nine years since The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies and barely 12 months since Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore flopped.

Nonetheless, the point was taken. Popular intellectual properties should be squeezed until dry, even if they’re based on a finite book series, singular three-volume novel, or, perhaps, simply the artistic creation of a single voice. Or at least a pair of them in The Matrix’s case.

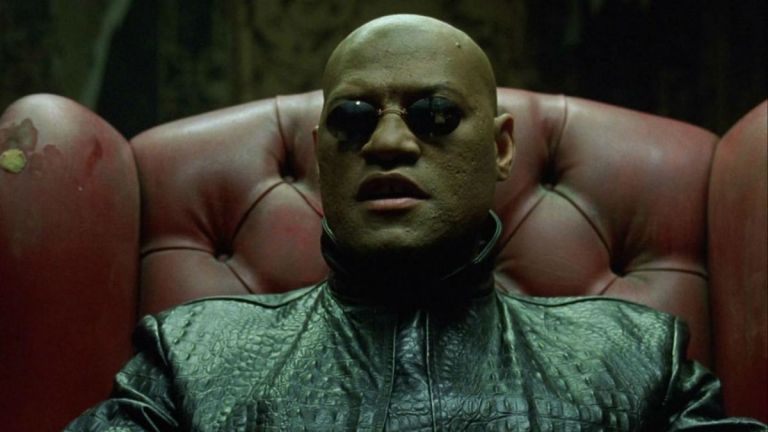

As of press time, The Matrix remains solely the province of the Siblings Wachowski in terms of the big screen. The pair wrote and directed the cinema-defining sci-fi masterwork that was released 25 years ago this week, and they also co-wrote and co-directed the less successful follow-up sequels released in 2003. But whether you like or loathe the cumulative effect of what became “The Matrix Trilogy,” there was no denying it was a complete work informed wholly by its directors’ interests and unique perspective of genre storytelling and the world they were creating.

Admittedly, only Lana returned to write and direct 2021’s The Matrix Resurrections, an odd and divisive legacy sequel that in actuality functioned more as a coda on the trilogy Lana co-directed 20 years prior. Still, it laid to rest (again) the story of Keanu Reeves’ Neo and Carrie-Anne Moss’ Trinity with a sense of finality. It also not so subtly satirized the entire enterprise of a studio continuing a franchise past the point of there being a natural story to tell.

The Wachowskis of course had left the door open to The Matrix becoming a creative sandbox in other mediums, including by producing The Animatrix anime films in 2003. However, the implication has always been that while the world of the Matrix is wide, its legacy and storytelling prism in cinema is limited. It is two storyteller’s narrative about a hacker who discovers he is living in a computer simulation and might be a messianic figure. And, honestly, it is fair to argue that the story found its best ending in 1999. Yet commercial interests dictated we return to Neo’s passion play time and again to diminishing returns—and now we might be continuing on without Neo at all.

All of which should provide some unease to anyone else who’s been less than impressed with the past decade’s obsession with expanding previously finished stories into endless “shared universes.” While the untitled fifth Matrix film’s press release never uses the term, the mention of “stories,” in plural form again, brings to mind when Disney CEO Bob Iger more bluntly let it be known at the beginning of the 2010s that the studio planned to release one Star Wars movie a year forever after acquiring Lucasfilm.

It also smacks of Sony Pictures attempting to turn what was once a great ‘80s comedy starring SNL alumni, Ghostbusters, into a shared universe. That one never quite took off, but you see the remnants of the plan still in last month’s Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire, which culminates in about a dozen folks wearing proton packs standing around in the climax doing nothing, and only one of them serviced with an actual arc in that film.

This is not to say the era of supersizing all IP until the well runs dry has been bad. Count this writer in the camp who thinks Star Wars: The Last Jedi is one of the best films ever released with the Lucasfilm banner. Disney+’s Andor is also the best Star Wars anything produced since probably 1980. Heck, I’m even looking forward to The Acolyte. Yet not even 10 years on since the first teaser for The Force Awakens promised you that “we’re home,” it’s hard not to wonder if our proverbial house is on the verge of collapse after so much oversaturation and exploitation. Star Wars once primarily meant a beloved trilogy of films with a significant role in film history. Today it’s another empty slogan on a plastic lunchbox.

Does The Matrix need to go the same way, especially after it’s already struggled mightily to justify any continuations after that 1999 classic? It’s easy to remain skeptical—and hopeful we’re not about to hear of a Matrix Max Original.