How Final Fantasy Changed RPGs Forever

These are just some of the ways that Final Fantasy one of the biggest and most influential video game franchises ever.

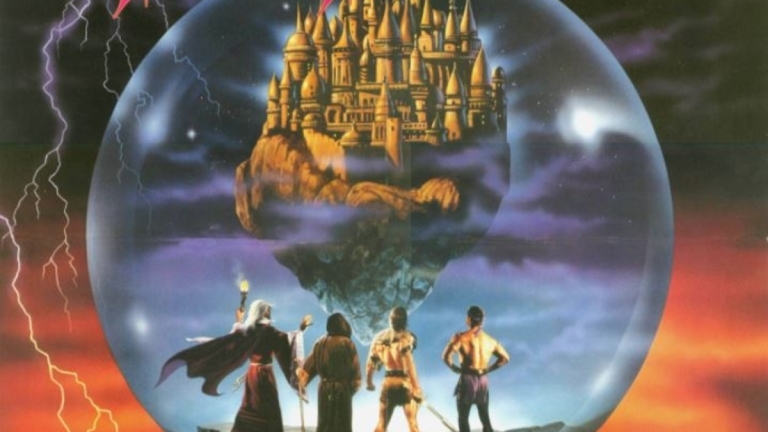

Final Fantasy is the most iconic and enduring RPG franchise in the world, first released for the Famicom in 1987 before being ported to the Nintendo Entertainment System for American audiences in 1990. Since then, the franchise has released over a dozen main titles, in addition to countless spin-offs, remakes, and evolved into a full-on multimedia empire for publisher Square Enix.

With a video game series as long-running and prolific as Final Fantasy, the franchise has introduced a number of innovations, not just to the RPG genre, but to the gaming medium as a whole. From changing how gamers thought what video games could be to pushing the technical limits of their respective platforms, Final Fantasy has often been at the forefront of the industry in one way or another. Here are some of the major gaming innovations introduced by the Final Fantasy series.

A Change in Perspective

Final Fantasy wasn’t the first RPG released for the Famicom/NES. Dragon Quest (which was released for the console 19 months prior) holds that honor. However, Dragon Quest utilized a first-person perspective similar to classic dungeon crawlers whenever the player entered a combat sequence. That tradition changed when the original Final Fantasy offered a shift in perspective that quickly came to define the genre moving forward.

Final Fantasy depicts the entire player party on the right of the screen and whoever they are fighting on the left side of the screen. Menus with combat options are overlaid on the right and bottom of the screen. Many subsequent RPGs (including Final Fantasy sequels) utilized a similar format to show the player characters on-screen in combat. This change gave players the thrill of seeing their favorite characters in action while emphasizing their importance in the adventure.

Games Within Games

Minigames are a hallmark of gaming that includes everything from fishing in The Legend of Zelda to the countless activities players can get into in the Yakuza games. However, they’ve long been utilized as popular brief distractions in otherwise epic RPG adventures. The original Final Fantasy features a hidden sliding puzzle that is considered to be the first minigame in an RPG. Remarkably, it wasn’t even originally intended to be in the game. Programmer Nasir Gebelli secretly added the minigame to the project.

Since then, the presence of minigames in RPGs has exploded, especially within the Final Fantasy franchise. From playing Blitzball in Final Fantasy X to the collectible card game Triple Triad in Final Fantasy VIII, there is a minigame for everyone in the series. Some popular Final Fantasy minigames even eventually received full games of their own, such as Chocobo Racing.

Bringing the JRPG Stateside

Of course, Final Fantasy’s role in introducing Japanese-produced RPGs, or JRPGS, to international gamers, especially in the North American market, cannot be overstated.

The original Final Fantasy sold 700,000 copies in North America alone. That may seem like a modest figure today, but compare it to Dragon Quest which was eventually given away to to Nintendo Power subscribers in 1990 to move unsold units. Granted, Final Fantasy and the JRPG genre would eventually endure varying sales numbers in North America compared to Japan, with producer Hironobu Sakaguchi admitting sales figures weren’t as strong in North America as Square hoped, even for legendary titles like Final Fantasy VI.

While this growing number of fans helped JRPGs like Chrono Trigger and Super Mario RPG stateside, it was Final Fantasy VII that forever cemented the genre’s place in North America. The title went on to sell over 14 million copies worldwide and helped the PlayStation become the biggest home console in the world at the time.

Experiential Learning

Final Fantasy, like many other RPGs, featured a leveling system that has players grow more generally powerful after earning experience points. This was changed in 1988’s Final Fantasy II, which replaced this system with one based on more specific experiential leveling. For example, characters that endure lots of damage might see buffs to their health bar while characters that rely heavily on magical techniques might see buffs to their magic meter and abilities instead of gaining conventional levels.

The Final Fantasy franchise ditched this leveling system by Final Fantasy III, but other RPG titles would take on a similar approach to their respective leveling systems. The most notable example of this is The Elder Scrolls franchise, which features a hybridized approach to its leveling system, with players gaining levels by improving individual skills through practice. Other franchises that use this system include Grandia and Square Enix’s own SaGa series.

Jobs Over Classes

Many fantasy RPGs, like Dungeons & Dragons, have characters in specific, static classes that come with their own set of skills, talents, and feats that players have to maintain for the entire run. Final Fantasy began with a classic class system but, starting with 1990’s Final Fantasy III, that was replaced with characters placed in various “jobs.” Instead of being forced into the job for the long haul, the game gave characters the option to change jobs as the game progressed.

These job changes are facilitated by capacity points earned after every battle, effectively allowing for greater character and party customization. The job system eventually paved the way for more elaborate multiclass builds in many modern RPGs that let players stray outside of the usual class constraints. Many future Final Fantasy would similarly use the job system, including the franchise’s online titles Final Fantasy XI and Final Fantasy XIV.

Pushing Technical Limits

Final Fantasy constantly pushes the hardware capacities of the platforms that the mainline franchise titles have appeared on. The original Fantasy Fantasy cartridge carried an internal battery to preserve save data rather than start fresh upon console restart, which was still revolutionary at the time. On the Super Nintendo, Final Fantasy VI was one of the major proponents of the console’s Mode 7 graphical interface, using it to create the illusion of 3D perspective when navigating the game’s overworld.

When Square developed Final Fantasy VII, it took advantage of the PlayStation’s technical capabilities through pre-rendered cutscenes, in-game backgrounds, and polygonal character models. Four years later, Final Fantasy X stood as one of the most gorgeously rendered games on the market at the time and, eventually, in the entirety of the PlayStation 2 library. This tradition of high graphical fidelity, full-bodied sound design, and gameplay refinements has been part of Final Fantasy from the beginning.

The Active Time Battle System

Many RPGs that revolve around turn-based gameplay are relatively passive in how they handle combat sequences. After starting out with this classic style, Final Fantasy switched to what it termed the Active Time Battle System with 1991’s Final Fantasy IV. During battle sequences, players are encouraged to input commands to enhance their attacks and techniques or react to incoming enemy attacks in timed windows.

This gameplay feature made the turn-based combat in Final Fantasy much more actively engaging for players and Square would refine it in future installments, most notably with Final Fantasy X’s Conditional Turn-Based System. Square would arguably perfect the Active Time Battle System concept in Super Mario RPG, with Nintendo employing it in their own future RPG Mario titles. This gameplay mechanic solidified that turn-based combat didn’t always need to be an entirely passive experience as Square exceeded conventional gameplay constraints of the genre.

Elevated Storytelling

When Final Fantasy debuted in 1987, the gaming industry still often relied on home console ports of arcade games that often featured bare-bones narratives. Final Fantasy offered an entire party of protagonists and a sweeping high fantasy story told on an epic scale right out the gate. By the time the franchise transitioned to the Super Nintendo, Final Fantasy had grown in scope and depth, weaving in extensive lore with operatic flair as it created new realms with each main installment.

Underscoring the heightened level of storytelling in Final Fantasy compared to its contemporaries was its memorable and varied musical scores. Nobuo Uematsu composed the scores for all the main games in the series from the 1987 original through 2002’s Final Fantasy XI. He would occasionally return to provide themes for subsequent titles. Through it all, Final Fantasy paved the way for an evolutionary blend of storytelling, visuals, and music that continues to endure for decades.

Going Online

When Final Fantasy XI was first released in 2002, the gaming industry was still in the earliest days of online console multiplayer RPGs (which had formally begun with the release of Phantasy Star Online for Dreamcast in 2000). Final Fantasy XI officially brought the franchise into the world of MMO gameplay and, unlike many of its contemporaries, it remains active over two decades after its launch. When a PC port was released later in 2002, Final Fantasy XI became the first major MMO title to offer cross-platform gameplay.

Final Fantasy XI has since received numerous DLC updates, with its first expansion launched in 2003 and its most recent debuting in 2020. This, along with performance updates, makes Final Fantasy XI among the first home console titles to offer online patches, instead of releasing supplemental physical media-based updates. These elements became the norm moving forward as online play and infrastructure became increasingly prominent parts of the industry.