Zappa Director Alex Winter Talks Preserving The Mothers’ Inventions

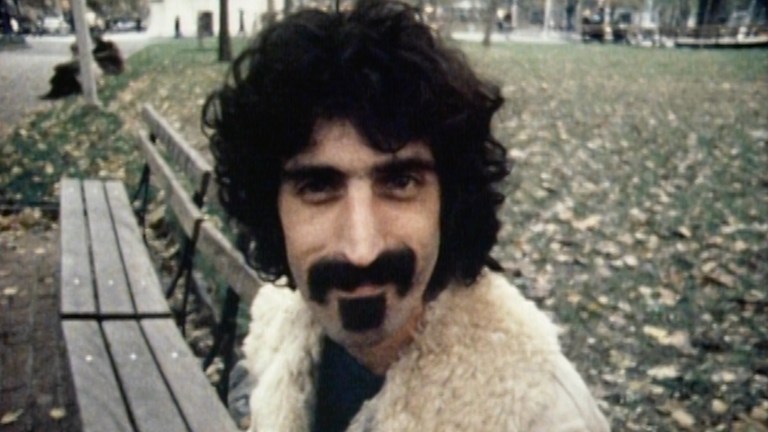

Alex Winter made a most excellent movie about Frank Zappa, and wound up saving his tapes and legacy.

Zappa is an intimate look into the innovative life and eclectic works of Frank Zappa, the composer. The Beatles, Brian Wilson, and Syd Barrett’s Pink Floyd pushed boundaries of what rock could do in the mid-1960s, but Zappa ignored any preconceived compositional restraint. He mixed rock with classical, jazz with chamber, and twelve-tone with Spike Jones. From his 1966 proto-punk, garage band debut, Freak Out, through the immediate experimental turns he took on Lumpy Gravy, We’re Only In it for the Money, and continuing through his career, Zappa’s music sounds unlike any other sonic unit.

Not only was Zappa a unique composer and bandleader, he was a ground-breaking film director, an innovative theatrical presence, and a voice of rebellion in worlds beyond music and the arts. His politics were far ahead of their time, and his critiques of society resonate strongly to this day. A vast majority of Americans know Zappa best because of his censorship battle with the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC), and the documentary censors nothing.

Zappa is not only the definitive documentary, but the only feature doc ever made on the pioneering founder of the Mothers of Invention with the Zappa family seal of approval. Not only did the family give director Alex Winter, best known as Bill from the Bill & Ted movies, permission to use the music and footage, they let him ransack the vaults. What he found there was a buried treasure in need of excavation.

Zappa’s storage area contained reels of unreleased music, archived appearances, home movies and hours of never-before-heard interviews, which allowed Winter to let Frank tell most of the stories himself. But first he had to save the vault material, which was disintegrating before his very eyes. He put together a crowdfunding campaign and raised over a million dollars to preserve the tapes.

Winter has been in entertainment all his life. He worked as a child actor in the mid-1970s, had co-starring roles in long-running Broadway productions like The King and I, Peter Pan, and The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, as a teenager, and studied filmmaking from behind the scenes at NYU film school. Besides the Bill & Ted films, he also had memorable roles in the vampire classic Lost Boys and cult favorite Freaked, which he co-directed. Winter also directed the criminally under-seen 1999 suspense thriller Fever. The bulk of Winter’s work has been on hard hitting and revelatory documentaries, like Downloaded (2002), Deep Web (2015), and The Panama Papers (2018).

Zappa is just as revelatory, but a lot more fun and you can dance to it. That is, if you can dance to what the London Symphony Orchestra called “irrational” time signatures. Towards the end of the film, Zappa shows exactly that. Alex Winter spoke with Den of Geek about Frank Zappa, as a musician, artist and subject.

Do you think Frank could have written the song to unite the world in Bill & Ted Face the Music, or would he have chosen to score the collapse of time and space or would he have made a double album?

Yeah, he would have told us to get lost and made like a quadruple album. No, I don’t. I think that he was so, in such a lovely way, so contrary that I don’t think he would have wanted to feel like he had that kind of pressure on him.

I read that you spent your Kickstarter money to preserve the material in his vaults. First, I want to say thanks for that and was there anything that actually was lost to the damage?

Yeah, a few things were lost. It was mostly the stuff that’s most sensitive like old film audio, like the audio track itself, the magnetic audio track was very fragile, we lost some of those. Some of that stuff was gone when we got to it and then some stuff really had like one run through a machine left before it was gone, so we were using extremely sensitive machines that had Sprocket LIS systems for digitizing and preserving that media. So, it was in various states. Some of the video was quite brittle. Some of that was gone but we got most of it and we got a lot of it. So that was good.

Besides the music, were there any unreleased films in the vaults?

Like full movies? No. We know what Frank made. I was able to preserve the negatives for Baby Snakes. We did include that in what we were preserving, so we found that there and we preserved it. So that’s nice and safe, that made me happy. But there weren’t full feature movies. There was a lot of Bruce Bickford Claymation that had never been used in anything that we found, a lot of which we put in the doc because it’s so good. And there were a lot of films, home films and there’s vast quantities of him just with a video or a film camera wandering around the house or around backstage or whatever, and that informed a lot of what we use. A lot of the stuff that we were using, he shot himself or just somebody who was in his house with him.

I love the editing, the scene with Frank playing with Moon Unit with the music behind it, was that something that you put together or was that something that was already edited in the vaults?

No. That was something that Mike Nichols put together, the editor. Mike really cut most of the media. We were even re-cutting Frank’s film media. We were really looking to tell a story and convey the narrative first and foremost, more than just presenting the stuff that Zappa had done. So, what we did was we started the film with things like the home monster movies that he made and the way he re-cut his mom and dad’s wedding footage. But we used that as a jumping off point for ourselves to start creating our own edits that made it, that felt like Frank’s world, but it was really just us.

Your documentary gets into how his music was criticized for being impersonal. I personally think some of his most beautiful lyrics come out in his guitar, but do you think his humor desensitized critics?

I think his humor put off some people, I don’t think he was particularly worried about that. I think that for me, coming up with Zappa when I got Zappa, part of that “get” was realizing that he wasn’t a rock and roll musician who made rock songs with funny lyrics. He was an avant-garde composer who used humor, like an instrument. Like using percussion or any other piece of your orchestra. It was something that he did to elicit a certain effect with the music itself. And once I kind of clicked in my head, I really got for myself, I don’t mean this needs to be for everyone because it’s personal, but it was an entry point for all of his music once that I grasped that idea.

In some of your other films you’ve tackled some very heavy topics. What draws you to the subjects? And how long have you been thinking about doing Frank?

Well, we started putting a sizzle reel short together, Glen Zipper my producer and I, after coming off of Deep Web, the tech doc we made about the dark net and federal criminal trial of Ross Ulbricht and the Silk Road black market. And I’d been very embedded in that story for a few years and I was ready to do something that wasn’t tech oriented and wasn’t quite so bleak. Glen and I were wondering why no one had tackled Zappa’s story. It seemed like it was such a perfect story for a documentary, given that he’s a big popular cultural figure, but also as a person who had so many different facets to his nature, which makes for a very good doc subject. So, that was about six years ago and we started putting something together, and then I pitched it to Gail and then the ball very slowly started to roll.

You submitted an audition film to the Zappa family, what was the short film like and how was the initial reaction?

It was very much like this to be honest with you, Mike Nichols cut that as well, and we were interested in conveying Frank’s emotional inner life, and not just the kind of pop B reverent story about the Zap that we felt people either already knew, or wasn’t really truly that representative of who he was. So we created it, it was very short, it was almost like a mood piece. But it did convey the idea of telling a story mostly with archival and Zappa’s voice that leaned on his emotional, inner narrative and not so much on being a music legacy doc.

Your film shows him as a hero, both politically and artistically. How much did you know going in?

I knew quite a bit of what made me want to do it. I knew all the primary biographical details of his life. There was an enormous amount I didn’t know, and there was an enormous amount I discovered making the film, but I certainly knew the bulk of the landmark periods of his life. And then once we started the preservation project and I was able to really spend time listening to Frank talk, because there was so much media down there that had never been heard, that was just him speaking candidly to either other journalists or to friends, and this was stuff that wasn’t public. It gave me a window into his thinking that I didn’t have before, and that guided me tremendously.

I loved Ruth Underwood’s story about dropping out Juilliard after seeing the Mothers at the Garrick Theater. Has she ever played the triangle since?

It’s a good question. I honestly don’t know, my guess is not.

Do you think Frank’s PMRC activisms sidetracked some music he might’ve been making?

No, I don’t. I think that he was in a period of reflection at that time. He never stopped making music during that time. He kept cranking. He was cranking away all through that period. He also began to work on the Synclavier and had an enormous output of music with a Synclavier during that whole period as well. So there wasn’t ever really a period where Frank wasn’t making music, and the political commitment that he had to cultural and political issues, I think really helped him, given how bleak the state of the country was and the state of the arts in the country was. So rather than just sit on his hands and moan, he just got active.

You covered pretty much every era of his career, but what is your favorite period and why?

Well, my favorite of Zappa’s early albums is Hot Rats, so that period is my favorite period, though I equally love the orchestral music that he made, and I love the Ensemble Modern period as well. Which shows you that I liked him at both ends of his career. I don’t leave out the middle, but both of those eras moved me and I listened to them equally. If someone put a gun to my head and said, “You get to jump in a time machine and go visit Frank at any given point, where would you go?” I would go to the Garrick Theater.

I came up doing theater in New York. And I’m very inspired by the fact that he wasn’t taking off in LA the way he wanted to, and rather than change his sound or capitulate to some popular movement, he just left and further investigated his own artistic voice. I have huge respect for that, and I would have loved to have been around when he was just throwing spaghetti at the wall artistically day after day at the Garrick.

Do you think that he was inspired by the movements in NYC theater?

That question I do know. Funnily enough, that’s one of the first things I asked Gail. When I first started talking to Gail in 2015, and we were just riffing and I was just trying to probe her brain to get a better sense of Frank, I was convinced by what I knew of the Garrick, that Frank was plugged into all the incredibly avant-garde and cutting edge theatrical movements of that time, which were so flourishing in Berlin, London, and New York, especially. And I said, given how theatrical his music always was, and his performances always were, surely he was inspired by this. And she said, “No.” As far as she knew, he had no interest in theater at all, and had no knowledge of any of the innovations or any of the people who were spearheading theater at that time. Which I thought was somewhat surprising, but apparently this was just his thing.

I’m sure you’ve seen Brian De Palma’s Hi Mom!, which had a scene of confrontational theater. When I think about Frank bringing the Marines onstage to dismember a doll, it seemed like one was feeding into each other.

Completely. I’m very versed in that world and it’s a big part of what I care about, and also the work that Dario Fo was doing in Italy at that time was really powerful. A lot of antiwar and protest art, but really not politics. Art was before politics in terms of the way that the theater was constructed. And that’s what seems similar to me about Frank, there were a lot of political undertones, but the art was first. And I was surprised that he wasn’t plugged into that, because they were literally running on parallel tracks at that time.

I know that your parents were dancers and Frank made music that was very hard to dance to.

And hard to edit. You try editing to that, with the rhythm changing as constantly as it does in such intense ways. It’s tough.

Actually that’s what I want to ask, you’re also a musician, do you map out rhythms, do you count out things and try to chart them in your head as you’re listening?

Mm-hmm, I do sometimes, but with some artists like Zappa or Coltrane I really don’t. I just go with the flow because the flow is so specific and untethered to formal music. So I don’t with them, but I do sometimes. Sure.

What other rock documentary makers were you looking at when you were making this?

I was most inspired even not making a music doc. I’ve been very inspired by the photography and the film work of Robert Frank. This movie was very inspired by Cocksucker Blues. There are techniques that we were doing and ideas that I had that were pretty much just lifted straight out of that movie without being overtly plagiaristic. That’s probably my biggest influence in terms of something if I had to point to, but obviously Pennebaker’s work and the Maysles and all of that. And I also have great respect for the work of Brett Morgan, he’s done amazing things, I thought Montage of Heck was phenomenal and really did an amazing job of looking at the interior life of someone who’s also quite detached. So that was helpful.

Steve Vai talks about how Zappa pushed musicians and the other musicians said being in his band was like going back to school. What did you learn in your craft from making this?

You learn a lot by being in the presence of genius like this. So I learned on an abstract level, I was inspired. I really respected the way he pulled from different genres and still made work that was his own. I was inspired to keep going, and it’s frowned upon to play in different media in our culture. People want to put you in a box, and I’ve never wanted to do that. I’ve acted and I’ve made films and I’ve made narratives and I’ve made shorts and I’ve directed all different kinds of stuff. And I would like to continue to explore like that and Zappa, he gives you the inspiration to feel valid in that way.

Magnolia Pictures will release Zappa on November 27.