Netflix’s Hollywood: The History of the Real People in the Series

Ryan Murphy and Netflix’s Hollywood is a fairy tale version of some very real Tinseltown tales.

This article contains spoilers for all seven episodes of Hollywood.

“When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” That line from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, the last masterpiece from one of Golden Age Hollywood’s most revered directors, John Ford has become pretty legendary itself. Yet it seems Ryan Murphy and Ian Brennan decided to do Ford one better in their version of Hollywood: write the fantasy.

Running across seven episodes on Netflix, Hollywood is far more a golden hued fairy tale than even Quentin Tarantino’s vision of 1969 Tinseltown in Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, and yet the Murphy series is both inspired by and written around some very real people. A few of them were the biggest movie stars of their eras, and others were dreamers denied or discarded from the promise of a life in the spotlight. Here are some of their stories.

Rock Hudson

A good place to begin is with one of Hollywood’s lead characters. Played as a sensitive and fumbling goliath by Jack Piercing, Hudson transforms from country boy to out and proud gay heartthrob in the series. While the real Hudson was indeed championed by Hollywood agent Henry Willson (more on him later), his real-life counterpart obviously did not become an out-of-the-closet icon on Oscar night 1948.

The real Hudson was born Ray Harold Scherer Jr. and came from a small Illinois town 16 miles outside of Chicago. After high school, the man who would be Rock enlisted in the U.S. Navy to participate in World War II, where he served in the Pacific Theater. In 1946, he made his way to Los Angeles, albeit initially to reunite with his biological father, who’d abandoned his family when Rock was a child during the Great Depression.

Hudson eventually got into acting after sending his headshot to Willson, who quickly took Hudson on as a client. Willson was also the one who changed his name to “Rock Hudson,” which the aspiring actor initially hated. While Rock’s teeth really were capped at Willson’s insistence, the actor lowered his voice not by screaming “like a banshee” with a cold, but by having throat surgery.

Hudson’s first film was a tiny scene in WB’s World War II drama, Fighter Squadron (1948). Even though he had only one line, it took 38 takes for Rock to get it right, something Hollywood spoofs when his Meg screen test lasts an even more staggering 67 takes. Still, Hudson eventually got a contract at Universal where he received lessons in acting, dancing, horseback riding, singing, and fencing.

Hudson didn’t become a star until Magnificent Obsession (1954), a romantic melodrama where Hudson’s reckless hero grows into a serious-minded surgeon who cures his intended lover’s blindness. It paved the way for Hudson to star in actual good movies like George Stevens’ Giant (1956), for which Hudson was nominated for an Oscar, and then to eventually become a romantic comedy star. His films with Doris Day, particularly Pillow Talk (1959), remain classics of the form as they began introducing sex farce into the familiar Hollywood formula.

But what Hudson is probably best remembered for today is his personal life—and that he was deeply in the closet as a gay man. In 1955, Henry Willson had to offer up dirt on two other clients to prevent Confidential magazine from publishing an exposé on Hudson’s sex life. Shortly afterward, Hudson married Willson’s secretary, Phyllis Gates, although the arrangements of their marriage still remain contested by historians and journalists, with some speculating she blackmailed Hudson over his homosexuality after their divorce three years later, and others saying Gates herself was a lesbian.

There was no happily ever after for Hudson, who became what Joan Rivers described as “the face” of AIDS after disclosing he had HIV in August 1985. Up until that point, he’d denied for years being gay. After his admission, which came several months before his death in October 1985, awareness increased for the disease and the gay community… even though President Ronald Reagan did almost nothing to combat it or even publicly mention AIDS, despite being friends with Hudson.

Henry Willson

Arguably the highlight of Hollywood is how Jim Parsons plays Henry Willson with scene-stealing tenacity. Literally described by biographer Robert Holfer as “The Man Who Invented Rock Hudson” (hence the title of Holfer’s book), Willson’s greatest success is glorified and satirized by the Netflix series. Of course Rock was just one of the many hunky young male stars Willson kept in his stable…

The real Willson broke into Hollywood on a steamship. Quite literally. After leaving Manhattan, where he wrote gossip columns for Variety, Willson took a steamer through the Panama Canal to Los Angeles in 1933. On board was actor and singer Bing Crosby’s wife, Dixie Lee, who Willson so charmed that she got him a job writing for Photoplay magazine. His first article? A profile about Bing and Dixie’s newborn, Gary Crosby. Willson was soon writing for The Hollywood Reporter and New Movie Magazine before jumping over the line between making movies and writing about them.

He began as a junior executive at the Joyce & Polimer Agency and soon moved to another owned by the forgotten fourth Marx Brother, Zeppo, before then working for David O. Selznick at the peak of his post-Gone with the Wind 1940s power as the head of Selznick’s casting department. All of which paved the way for Willson to open his own agency in 1944.

Before Rock, his likely biggest discovery was the future blonde bombshell Lana Turner. Willson had been introduced to her as Judy, a student at Hollywood High whose ability to fill out a sweater caught his eye. He renamed her Lana in 1937 and introduced her to Mervyn LeRoy at WB. The rest is history (including Lana’s own scandalous future that included the murder of her boyfriend). However, it’s fair to say Lana wasn’t the type Willson was known for.

Long before signing Rock, Henry developed a reputation for cruising the Sunset Strip gay bars where he promised young men professional opportunities for personal favors. His first client was actually a lover named Junior Durkin, who died in a 1935 car collision. And other than Rock, his stable included stars like Tab Hunter, Robert Wagner, and Guy Madison, most of whom Willson personally renamed. His demand for casting couch cooperation from his mostly gay, bisexual, or desperate male clients was such an open secret around town that Ann Dornan told biographer Suzanne Finstad how when she discovered a young man had Willson for an agent, “It was almost assumed he was gay, like it was written across his forehead.”

However, his inability to keep his homosexuality from becoming common knowledge among the tabloids and columnists, and his own drinking and drug abuse, led to Willson becoming a pariah by the 1960s. There was no future career as a Hollywood producer for Henry, despite what Ryan Murphy tells you. Rather young up and coming actors, gay and straight, began distancing or avoiding Willson in order to avoid being labeled gay by studios and journalists. When Willson died at the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital in 1974, he was so poor that he was initially interred in an unmarked grave.

Hattie McDaniel

She’s so nice! That’s the takeaway from the brief but pivotal cameo Queen Latifah has as Hattie McDaniel. In the second of her two scenes, she sits down with Camille Washington (Laura Harrier), who is depicted in the series as the first glamorous African American movie starlet. Nicer still is how Hattie gives Camille pointers to campaign for an Oscar in the Lead Actress category for Meg, providing tips that no one in Hollywood followed until Harvey Weinstein. Yet in this show, it’s happening in ’47 as a sweet passing of the torch… McDaniel’s legacy and her real relationship with the next generation of African American talent, particularly the actual first glamorous movie star of color, Lena Horne, was a lot more complicated.

As the show hints, McDaniel was born the daughter of slaves—a fact that the MGM publicity department chose not to publicize during the release of Gone with the Wind. Her father was even permanently injured after fleeing a Tennessee plantation in 1863 to join the Union Army, where he lost toes to frostbite, and was facially disfigured by battlefield wounds. Hattie was raised in turn of the century Kansas and Michigan to be a cook and housekeeper like her mother. But after seeing her brothers try their hand at show business, she dropped out of school at age 16 and began pursuing a career in entertainment.

She was 21 when she wrote the music and sketches to her first all-female minstrel show, where the black performers wore blackface, albeit this was likely more subversive of white stereotypes than the original minstrel shows that gave the world “Jim Crow.” At 38, McDaniel moved to Los Angeles to take a stab at Hollywood. Already a widow from her first of four marriages, she got a foot in the door with radio and then film. At the height of the Great Depression, Hattie was fine with playing maids, cooks, and servants in movies. “I could be a maid for $7 a week or I can play a maid for $700 a week,” she later said. She also created a niche by playing servants who talked back, rolled their eyes, and even quietly judged their white employers. This led to acting alongside African American Paul Robeson in James Whale’s Show Boat (1936) and it led to Gone with the Wind.

Often remembered now for the insidious implications of her character Mammy—the literal name of the racist white stereotype for subservient older overweight black women in minstrel shows—McDaniel portrayed a woman happy with being Scarlett O’Hara’s slave, and who’s even treated like a dear aunt (thereby “excusing” her enslavement). Yet Mammy was still more nuanced than any role offered to black actors in a major Hollywood film at the time. Unlike in Margaret Mitchell’s novel, McDaniel’s Mammy judges and even scolds Vivien Leigh’s Scarlett. Whether intentional or not by the white filmmakers, McDaniel becomes the closest thing to a moral compass or Greek choir in that movie. McDaniel told reporters for black newspapers she was inspired by the last generation of mothers born into bondage who’d raise innovators in the African American community like Booker T. Washington and Washington Carver.

Still, McDaniel was not permitted to attend the Gone with the Wind premiere in Atlanta. Additionally, while she was allowed to sit in the audience during the 1940 Academy Awards (despite what occurs in Hollywood), the Ambassador Hotel treated this as a special favor because it had a no-blacks policy and required her to sit at a table at the far end of the room. When she became the first person of color to win an Oscar, she said in her acceptance speech, “I shall always hold it as a beacon for anything I may be able to do in the future. I sincerely hope I shall always be a credit to my race and to the motion picture industry.”

Despite the triumph, and producer David O. Selznick signing her to a contract, the only major role she ever got again was a supporting part in In This Our Life (1942), in which she played the mother of a young black male who is wrongfully accused of running over a white pedestrian. Her speech about how black men are often discriminated against by police was removed from Southern prints of the film by Georgian censors.

Meanwhile Hattie had a contentious relationship with NAACP leader Walter White, as well as younger black performers, throughout the 1940s. She resented the NAACP’s calls for getting better non-subservient roles for black actors because she was part of a generation that feared it would cause the studios to stop casting black talent, or that would then replace them with a younger generation not typecast as “Mammy.” While she had an initially friendly relationship with Lena Horne, who she invited into her home, there was also some resentment.

“When you ask me not to play the parts, what have you got in return?” McDaniel told Hedda Hopper about requests to stop playing servants. And regarding Horne, she infamously said during an NAACP speech that Horne was “a representative of the new type of n***er womanhood.” She then corrected herself to say she meant “negro womanhood,” but once news reports of the event got out, it was effectively the end of her movie career.

In her personal life, McDaniel had four husbands, although some historians insist she was a member of the Hollywood Sewing Circle, which was a rumored collection of bisexual and lesbian actresses who were in “lavender marriages” with gay men. Hollywood plays this aspect up. No matter what, she was divorced for the final time when she died of breast cancer in 1951.

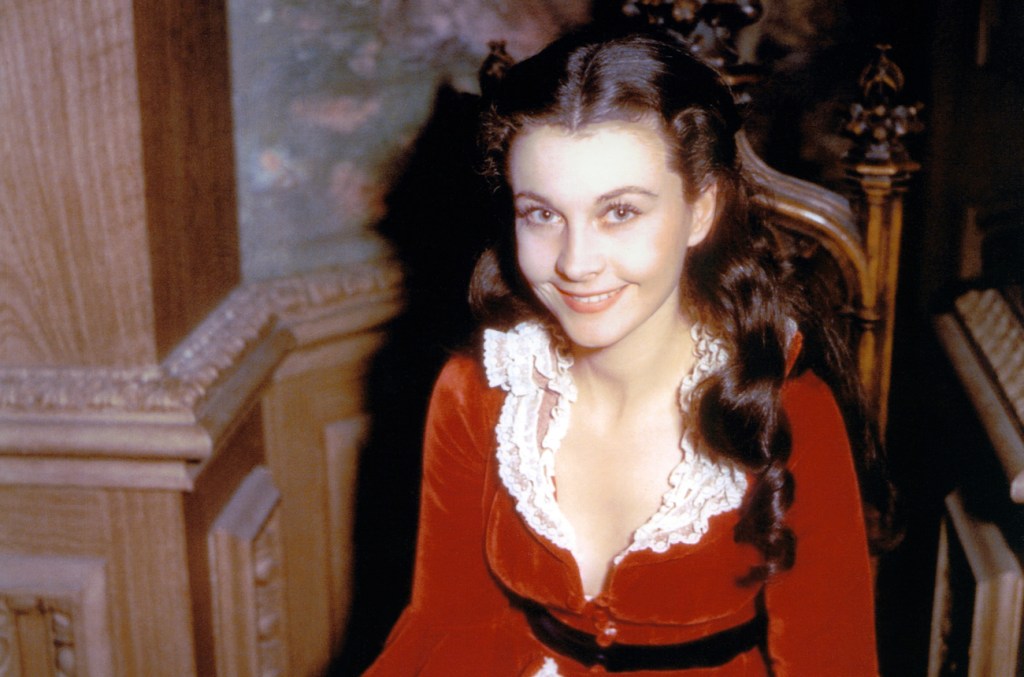

Vivien Leigh

But while ‘Mammy’ has a relatively major role in Hollywood, her dear Scarlett O’Hara appears more as a recurring joke. While played by Katie McGuinness as a flighty, vain movie star who needs to recite all of Scarlett’s best lines at dinner parties, and who is mystified about where “Larry” is, the actual Leigh did suffer from “episodes” of bipolar disorder and was married to her then husband, Sir Laurence “Larry” Olivier, during the series’ 1947 setting.

Born Vivian Mary Hartley in 1913 British India, Leigh was the daughter of a British cavalry officer before discovering in boarding school she had a passion for acting. She was 13 by the time of her first success on the London West End stage and continued to have early triumphs, including when she met the love of her life, Laurence Olivier, at the age of 23 in 1937. Beginning an affair with the fellow thespian while acting in the British film Fire Over England, the pair seemed semi-charmed, except for the small matter of each being married to someone else. No matter!

Their marital status became a problem for both of them, however, when they reached Hollywood, with Samuel Goldwyn’s PR team needing to disguise the bohemian lifestyle of their new Heathcliff leading man in Wuthering Heights (1939). Leigh came to Los Angeles to be with Larry but refused director William Wyler’s offer to play a supporting role in the film—she wanted to be Cathy or no dice. Luckily, she also wanted to be Scarlett O’Hara. Like every other aspiring actress, she read Gone with the Wind in 1936 and thought she’d be perfect as Scarlett; she even told her agent to instruct producer David O. Selznick to make it happen. However, Selznick saw Leigh in Fire Over England and deemed her “too British.”

Legend has it that Selznick’s brother, Myron, brought Leigh and Olivier to the Gone with the Wind set where they were already burning Atlanta, to lobby for Vivien. David agreed to a screen test and sure enough, he had his Scarlett. Despite a public outcry, especially in the South, about an English woman living with not-her-husband playing Scarlett, her performance as the ultimate Southern Belle fantasy in the most popular movie of all-time became the stuff of myth, winning Leigh her first of two Oscars.

Afterward she grappled with Selznick on future roles, often wanting to work with Laurence as newlyweds (they both finally shook off the exes with divorce papers in 1940), and appearing with him on Broadway in Romeo and Juliet. During World War II, she and Olivier went back to Britain where they starred in That Hamilton Woman (1941), an Alexander Korda film about mistresses and fighting the Napoleonic Wars (but really about why America needs to help fight Hitler). It became a favorite of Winston Churchill’s, who made the Oliviers frequent drinking companions for the rest of the war and beyond. During this time, Leigh also starred as Cleopatra opposite Claude Rains’ Julius in the film version of Caesar and Cleopatra (1945).

As Hollywood picks up in ‘47, this is near where we meet her, albeit given she was then starring in productions at London’s Old Vic Theatre, where Larry was now serving on the board of directors, that seems hard to track—as is her preparing to star in the West End debut of Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire, since that play did not open in the UK until 1949. Although Leigh would play the main character of Blanche DuBois in the Hollywood version in 1951, winning her second Oscar for the performance.

These idyllic successes, however, were drenched by a shadow. Olivier claims to have witnessed her first episode of depression in 1938, but what we now call bipolar disorder didn’t become fully manifest in Leigh until after a miscarriage while filming Caesar and Cleopatra in ’45. This was one year after she was diagnosed with having tuberculosis in her left lung, which while seemingly cured, only added to the “fits of hysteria” she suffered after losing a child.

In 1953 she was fired from Paramount’s Elephant Walk after suffering a nervous breakdown, being replaced by Elizabeth Taylor. During this particularly violent episode, the Oliviers couldn’t hide her battle with mental illness and friend David Niven said she was “quite, quite mad.” Laurence even committed his wife to a mental hospital where she was left with scars from the experimental electroshock therapy she underwent. This was the beginning of her real decline, not the laughed off “hospitalization” thrown away in a line of Hollywood. In ’56, she suffered another miscarriage and, after another subsequent bout of depression, followed Laurence on a European tour of Titus Andronicus where their fights became a nightly occurrence for the crew to endure. One of them left Vivien with a black eye hidden beneath an eyepatch.

The pair were divorced in 1960, and while Leigh moved on, she discovered her tuberculosis resurfaced in May 1967. She was dead by July at the age of 53.

George Cukor

Meanwhile Leigh’s first director on Gone with the Wind—a production he was famously fired from—also appears briefly in Hollywood: George Cukor. A smaller role on the show, he’s merely the famous movie director whose house party turns into a swingers’ event. This is harder to square away because while other wealthy gay men in Hollywood are more widely known to have partaken in libidinousness parties, including the publicly closeted Cole Porter or the openly gay James Whale (director of Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein, and The Invisible Man), only recently have such stories started circulating about Cukor.

Generally speaking, Cukor is remembered for being quite self-loathing given his generally bookish and unhandsome appearance while surrounded by Hollywood beauty, and most of all for being deeply closeted. For decades after his 1983 death, Cukor has been recognized as the center of “gay Hollywood,” in terms of successful celebrities and filmmakers who stayed in the closet but kept a discreet network open. Yet these pool parties are attributed to him by Scotty Bowers (more on Bowers in a moment). Beyond that element in the series, Cukor was an urbane and bespectacled director celebrated for a string of classics, but regarded in his time as being primarily the filmmaker of period dramas and “women’s pictures.”

Famous Cukor movies include Little Women (1933), The Women (1939), The Philadelphia Story (1940), Gaslight (1944), Adam’s Rib (1949), A Star is Born (1954), and My Fair Lady (1964).

Cole Porter

Speaking of Cole Porter, he shows up in the first episode of Hollywood in a gag as a pants-less John waiting to be serviced by one of the stud muffins working at the series’ Dreamland gas station. The real Porter is very much the American musical hero Dylan McDermott’s Ernie jokingly bows down to. A classically trained composer and American songwriter, he is considered one of the most important contributors to the American songbook of the 1920s and ‘30s, as well as one of the earliest innovators of the now modern Broadway musical.

Some of his most famous compositions include “I’ve Got You Under My Skin,” “I Get a Kick Out of You,” “Night and Day,” “Begin the Beguine,” “In the Still of the Night,” and pretty much the whole songbook of Kiss Me Kate.

Anna May Wong

Anna May Wong is recognized as the first Asian American movie star, hence her justifiably bitter disappointment at how Hollywood treated her, as fairly assessed by the Netflix series. Hollywood mostly reminds you of how incredulous it was that Wong (Michelle Krusiec) lost the role of a Chinese character named O-Lan to the lily white Luise Rainer in MGM’s The Good Earth (1937). However, that was just the biggest personal setback in a career filled with them.

Born to second generation Chinese American parents living in 1905 Los Angeles, Anna (born Wong Liu Tsong) saw the fledgling movie colony spring up around her. Hollywood mutated from being a sleepy annex of Los Angeles to the movie capital while she came of age, and Wong in turn became fascinated by the silent moving picture. She broke into film by becoming an extra in The Red Lantern (1919) without her father’s permission. By 1922, and at the age of 17, she got her first leading role in the first two-color Technicolor film, The Toll of the Sea. She’d become a star at 19 by playing a scheming Mongol slave opposite Douglas Fairbanks in The Thief of Baghdad (1924).

However, she soon learned the limit of such roles, as throughout her life she continued to be cast as “native” and “exotic” roles, from Tiger Lily in a 1924 film of Peter Pan to Princess Ling Moy in early Dr. Fu Manchu talkie, Daughter of the Dragon (1931). Laws against “miscegenation” in the South made it impossible for her to get a lead role where she could have an actual love interest with a male co-star (and the later Hayes Code prohibited interracial relationships). She was constantly cast in “Dragon Lady” parts, even in films like Marline Dietrich classic, The Shanghai Express (1937).

After visiting her family’s ancestral Chinese village in the late ‘30s, she focused on starring in B-movies that depicted Chinese-Americans and immigrants in a positive light, and raising money to help China against Japan during World War II. She largely retired from movies in the ‘40s, but became the first Asian American lead of a television series by starring in 1951’s The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong.

Irving Thalberg

Irving Thalberg appears in Hollywood for a single flashback to the “old days” on the set of The Good Earth (1937). Thalberg, the New Yorker son of Jewish immigrants, is also considered one of the greatest movie producers of the Hollywood Golden Age who might’ve become even more legendary if he didn’t work himself into an early grave. Getting his start at Universal where he made his name producing Lon Chaney Sr. horror movies like The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), he quickly moved to Louis B. Mayer’s new MGM where Thalberg helped build the studio’s status as having “more stars than in the heavens.”

During his time at MGM he helped turn Joan Crawford, Greta Garbo, Clark Gable, and Norma Shearer into movie stars, the latter of whom became his wife. He also was an innovator, being dubbed in the 190s as a “boy genius” by Cecil B. DeMille. He helped pioneer the first American horror movies at Universal, pushed MGM to make the first movie with an all-black cast, and created the concept of “story conferences” and “sneak previews.” In 1936, at the age of 37, he died of pneumonia.

Hedda Hopper

The infamous Hollywood columnist makes a brief cameo during the final episode of Hollywood when she interviews Parsons’ Henry Willson. Originally Hedda wanted to be a movie star herself, coming to nascent Hollywood in 1923 after already starring in silent films back in 1910s New York (and a failed attempt to become a Ziegfeld Follie). She was a contract player for Louis B. Mayer Pictures throughout the ‘20s but never became a star.

So she became a Hollywood gossip columnist, and one of the industry’s most famous and PR-shaping personalities. At the height of her popularity in the 1940s, Hopper’s Los Angeles Times columns were syndicated around the country with a readership of more than 35 million Americans. However, she is now largely looked back at with scorn and infamy for being one of the loudest megaphones and champions of the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee.

A staunch anti-Communist, she named supposed Communists in her columns, worked to ruin careers, and helped lead the Motion Picture Alliance for Preservation of American Ideals, a group that invited HUAC to Hollywood and helped publicly enforce the blacklist. She also outed anyone she thought was perhaps a communist but definitely a homosexual in her columns as being gay. So her being so non-responsive to Rock Hudson coming out as gay on Oscar night in Hollywood, which takes place during the Red Scare, is a bit strange.

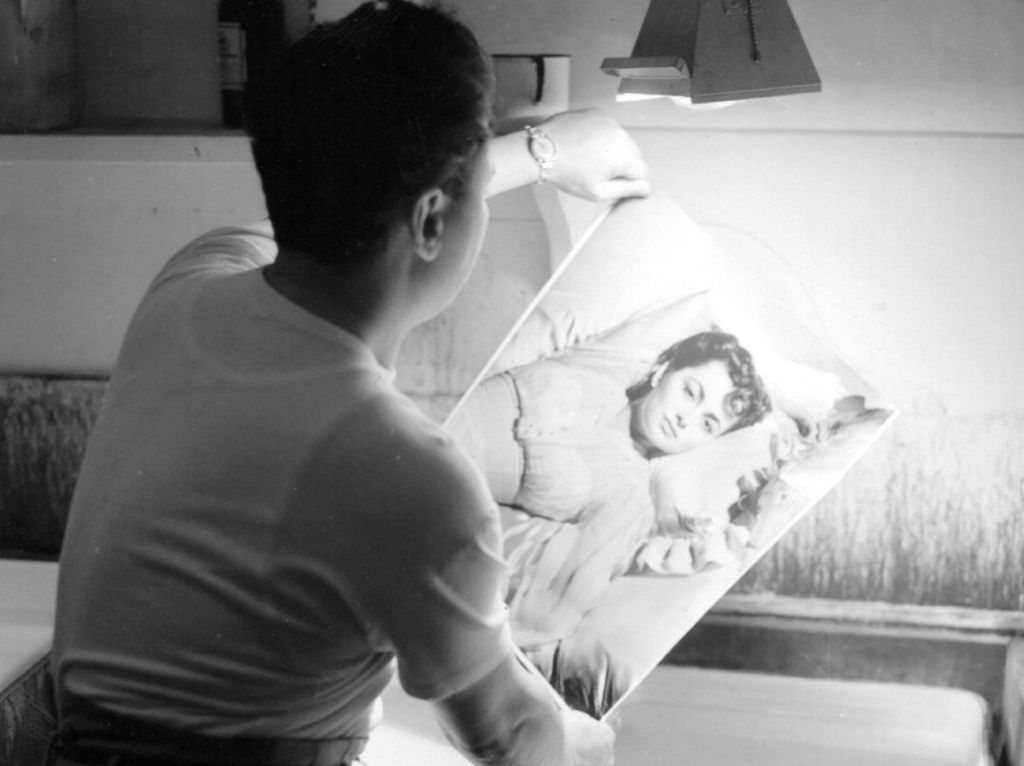

George Hurrell

George Hurrell also briefly appears as the glamour photographer who takes extravagant photos of Camille and Jack. He really was the go-to photographer for movie star mythmaking in the 1930s and ’40s, and is responsible for likely many of the most striking black-and-white photos you’ve ever seen of the Golden Age stars. He was hired at the beginning of the ’30s by Irving Thalberg (him again) to help craft the image of MGM stars who included Jean Harlow, Clark Gable, Joan Crawford, Anna Mae Wong, Carole Lombard, Rosalind Russell, and more. He also moved for part of the 1940s to WB where he is responsible for striking images of James Cagney, Bette Davis, Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and the visual mythology around Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. He also helped build up Rita Hayworth’s visual iconography at Columbia.

During World War II, Hurrell participated in the First Motion Picture Unit for the United States Army Air Forces. He continued to work in Hollywood in the ’40s, including taking that infamous Jane Russell photograph for Howard Hughes on The Outlaw, but after his style fell out of favor in the ’50s with the advent of an earthier reality brought about by post-war cynicism and Method acting, he ended his career working in advertising.

Mickey Cohen

I’m pretty sure the gangster Henry Willson gets to beat up a tabloid journalist is supposed to be Mickey Cohen (he’s just called Mickey in Hollywood). Mickey was a wiseguy who came up with Jewish crime outfits in Prohibition era New York before working for Al Capone in Chicago and then Meyer Lansky and Bugsy Siegel in Cleveland. In 1939 he carved Los Angeles out for himself when Lansky sent him to the west coast to work with Bugsy, who was building the Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas.

Mickey’s reign was relatively brief after the U.S. Senate Committee known as the Kefauver Commission took a page out of Chicago’s playbook and pinched Mickey on tax evasion in 1951.

Scotty Bowers

Scotty Bowers does not appear as an actual character in Hollywood but his presence is paramount in the project. It was while discussing his memoir, Full Service, that star Darren Criss (who plays Meg director Raymond) and Ryan Murphy first got the idea to make a TV series set in the underground gay community of 1940s Hollywood. However, Bowers wasn’t technically gay; he was a veritable sexual Olympian as well as an entrepreneur.

With the 2012 publication of Full Service, Bowers (who passed away in 2019) revealed that he operated a prostitution ring that serviced, among others, the stars out of a gas station on the corner of Hollywood Blvd. and Van Ness Avenue. Happily providing sexual relief to men and women for a price, he and his ring of men (and some women) became the toast of parts of town, a feat that appears genuine considering the ring’s been hinted at for decades, and actor Beach Dickerson left Bowers multiple houses in his will (after naming a racehorse after him).

However, the extravagant depth of Bowers’ claims personally strikes me as a little more dubious. He says he waited until he was in his 90s to come forward because all of his famous partners and clients were dead and couldn’t be embarrassed, but they also couldn’t sue. A sampling includes George Cukor, Cole Porter, Bette Davis, Cary Grant and Randolph Scott (together and separately), Ava Gardner and Lana Turner at the same time, Vivien Leigh while some of his male tricks handled Laurence Olivier, Spencer Tracy while female tricks handled Katharine Hepburn, Rock Hudson, setting Rock Hudson as an employee up with Cary Grant, Tennessee Williams, Bob Hope, Errol Flynn, William Holden on the night they shot the end of Sunset Blvd., and no less than J. Edgar Hoover and Edward VIII, the former King of Britain.

Given the veritable who’s who in his kiss and tell, I take a large helping of salt with it. But he was still a former U.S. marine who fought in Guadalcanal and Iwo Jima, the latter of which his older brother also fought and died at. Obviously Hollywood’s Jack Castello (David Corenswet) and Dylan McDermott’s Ernie are both based on Scotty, with Jack as the young hunky World War II vet looking to support his family by jumping in the pool, and Ernie as the actual pimp who ran the show. For the record, Jack also appears to be based on Audie Murphy, the Western actor and future movie star who did fight in the Battle of Anzio like the fictional character. However, he did not turn tricks. In fact, he was a nationwide war hero after receiving the Medal of Honor for holding off a whole German company by himself.

Lena Horne

Another historical figure who doesn’t actually appear in Hollywood but seems to be a major influence on it is Lena Horne. Arguably the first African American movie star, and certainly the first glamorous one who was meant to appeal to all audiences, Horne came to prominence in Tinseltown during the World War II years.

Prior to Hollywood, Horne was a nightclub singer who broke in at Harlem’s famed Cotton Club–a joint where black performers danced and sang for white-only audiences–and while it’s where her career began, Horne did not have fond memories of the working conditions or the cynicism of the fellow showgirls she leapfrogged over because of her looks and probably her lighter skin tone. Actually raised in an upper middle class subsect of the black community in first Brooklyn and then Pittsburgh, Lena found her element more at the Cafe Society in Manhattan. There she commiserated with bandleader Charlie Barnett and liberal intellectuals in the audience like Orson Welles… she actually began a years long affair with the future Citizen Kane filmmaker by the time they were both in Hollywood and while he was making Kane, which might influence the relationship between Camille and Raymond on Hollywood.

MGM eventually signed her in 1942 to be their first African American actress groomed for movie stardom and glamour girl sophistication. MGM, which had made one all-black musical in 1929, came to the realization that African American audiences go to the movies too! As we live and breathe… Horne became the talk of the black community in this time (much to the chagrin of some older actors like Hattie McDaniel) and would star in the studio’s second all-black musical, Cabin in the Sky (1942). Yet her star power was cemented in 20th Century Fox’s Stormy Weather (1943), which had Horne sing the titular scorch anthem and make it her own.

Yet Horne’s time in Hollywood was always bittersweet because she was often viewed as “haughty” by the local black community due to her rubbing shoulders with an almost all-white industry, as well as dating white men with her lighter skin, while still almost never getting lead roles from those white colleagues. Southern states refused to show either Cabin in the Sky or Stormy Weather, and their laws against interracial relationships also affected the Hayes Code, making it impossible for Horne to have a romantic relationship with white co-stars. And as there were no black leading men of her generation, or even black male actors required to do more than musical sequences or play servants, she wound up being wasted by MGM who continued casting her as glorified lounge act supporting characters.

During the war, she demanded to sing almost exclusively for black segregated soldiers on the USO Tour, and after the war she faced her biggest disappointment when MGM remade Show Boat in 1952. She wanted desperately to play Julie LaVerne, a major character who is biracial but can pass for white. Her career is ruined after local Southern communities discover she is half-black. Despite being a natural singer previously cast in “exotic” roles or as Spanish characters in the past, MGM passed her over, rationalizing she was too famous as a black woman for white audiences to believe she was anything but. They instead cast Ava Gardner, who needed to have her singing dubbed.

Even so, Gardner and Horne remained lifelong friends, and as Horne told it, she and Gardner would rehearse the project by going over to her house and getting liquored up on gin while singing showtunes each afternoon. Perhaps Camille and Samara Weaving’s Claire Wood in Hollywood are based on this friendship?