The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar Is an Extraordinary Adaptation of a Roald Dahl Story

With The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, Wes Anderson brings his distinct and evolving voice to the world of Roald Dahl.

This article contains The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar spoilers.

“The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” is only the second time in Wes Anderson’s career that he’s adapted another writer’s work. To put a finer point on it, “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” is also the second time he’s adapted a single author’s work: Roald Dahl. (The other time being 2009’s extraordinarily funny, but stop-motion, Fantastic Mr. Fox.) Yet with Anderson’s first foray into streaming, via his 41-minute short film soufflé on Netflix, Anderson is tackling Dahl in a very different manner, and we do not mean simply because “Henry Sugar” is live-action.

One of the most beloved children’s authors of the 20th century, Dahl has intermittently proved a wellspring for filmmakers over the decades, sometimes to Dahl’s personal chagrin. He infamously regretted the film version of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which couldn’t bother to even get the title right when Gene Wilder starred in Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory in 1971. However, we can attest many generations of children (including this big kid) never minded. He also strongly disliked elder millennial and late Gen-X touchstone, The Witches (1990), with Angelica Huston.

We wouldn’t dare venture to guess what Dahl would think of Anderson’s riff on his 1976 short story “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar,” but we’d daresay it is one of the most accurately droll and whimsical Dahl screen transfers to date. Which might be another way to say that it is distinctly a piece with Anderson’s overall aesthetic. Even so, it is the manner in which Anderson approaches Dahl this time that confirms an emerging obsession for filmmaker; he seems to need to draw attention to the artifice of storytelling and performance.

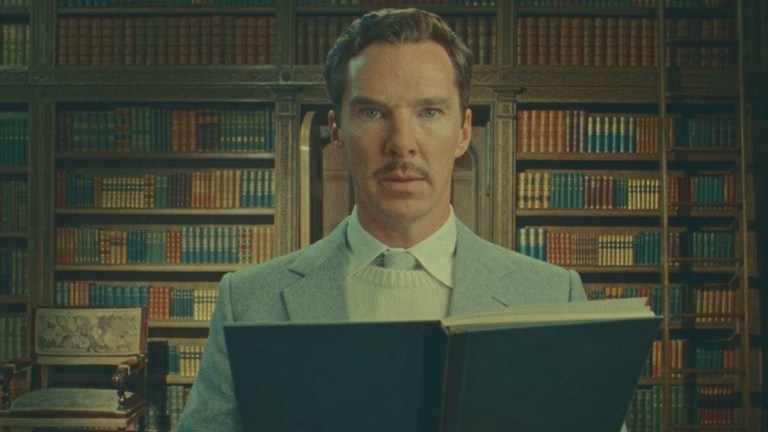

As an adaptation of the Dahl story, the “Henry Sugar” short film is fairly accurate to what’s on the page. Henry Sugar (Benedict Cumberbatch) is an Englishman of independent means (i.e. he’s filthy rich due to inherited wealth!). He’s a gambler and a bon vivant who discovers the story of a magician/circus performer who learned in India how to see through fabrics and around objects—although Anderson tightens to it “without my eyes.” Henry then spends three years developing the gift in order to cheat casinos. By the time he has achieved the ability to see without his eyes, however, he has also lost the taste for gambling when there is no chance he’ll lose.

In fact, the only major departure from the text is that Anderson excises a subplot where mobsters almost capture and kill Sugar for hustling their blackjack tables in Las Vegas. Intriguingly, if Anderson had developed that sequence and maybe a few more tertiary characters, he could’ve filled this out to a feature-length 80 minutes. But that would miss the point. Anderson clearly didn’t want this to be a feature; instead he gets expediently and economically to the point:

Henry must dedicate his life to hustling casinos incognito so he can use his winnings to bankroll the finest orphanages in the world. He keeps his operation so secret, he even only obtains a smattering of recognition for his works in death when our narrator (Ralph Fiennes) is convinced by Henry’s accountant (Dev Patel) to publish at least a version of how these events transpired.

And yet, what makes Anderson’s approach so specific to his aesthetic is that Netflix’s “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” is exactly that—it’s a version of the events we’re watching, one that’s being interpreted on an unmistakable soundstage and by a troupe of actors. All of them, including the Henry Sugar performer himself, Cumberbatch, even play multiple parts.

The artificiality of storytelling, performance, and art has always been at the forefront of Anderson’s work. His films exist within beautiful and impossible worlds of symmetry and color-coordinated expressions of melancholia or ennui. The beginning (and recurring through-line) of his second film, Rushmore (1998), is that of a precocious youth (Jason Schwartzman) inventing impossibly cinematic and professional spectacles, supposedly within the confines of a high school auditorium.

Still, in spite of their unmistakable artificiality, Anderson’s earlier worlds generally functioned with an insistence of authenticity, at least in regard to their own internal logic. That’s changed about a decade ago.

Beginning with what we’d argue is Anderson’s best film, The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), the filmmaker has become taken with exploring the limitations (as well as the luxuries) afforded by his tableaus. Grand Budapest Hotel is a story within a story, within a story—a veritable Russian nesting doll wherein a young woman (maybe of contemporary times?) reads a great writer’s interpretation of the ancient reveries spoken by Zero Moustafa (F. Murray Abraham and Tony Revolori). Each layer of this cinematic confection has its own color palette, aesthetic, and aspect ratio, with the bulk of the story occurring in a deceptively bucolic 1930s where Zero remembers with nostalgia both his great love (Saoirse Ronan) and his eccentric mentor (Ralph Fiennes). But this is a version of events that must be taken with a grain of salt; an attempt to find joy and beauty in a world that could no longer fit into the elegance of a pink pastry box after fascists rose to power.

Stories within stories, and meta ironies, have ever since been an element of Anderson’s films, from the New Yorker inspired periodical conceit presented in The French Dispatch (2021) to how this summer’s Asteroid City is a story inside a Sam Shepherd-like mid-20th century play, inside of a Wes Anderson movie. We’re watching the effect created by actors on a Manhattan stage and under the charge of a raging narcissist (Adrien Brody) while experiencing the grief of Asteroid City’s main characters.

“The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” dives yet further into this affectation. Like Dahl’s short story, Anderson’s film is derived from a journalist’s account of the life of “Henry Sugar” (a name which itself is revealed at the end to be a pseudonym). But Anderson takes one step further back by creating the illusion that this is a published story performed by a troupe of actors—his troupe of actors, in fact.

With multiple long tracking shots, we see how the actors pivot from set to set, and costume to costume. The mise en scène demands Cumberbatch change costumes between sets and in the same shot, or Patel narrating events while anxiously glancing over his shoulder and into the camera’s lens while running down a hallway.

The effect is to call constant attention to the fact that we’re watching a story being told, even read, to us. It’s more than self-aware; the point of the work seems in large part to be a meta-commentary on the purpose of storytelling. In this way, it has even caused confusion online, with more than one viewer asking on social media if Henry Sugar is a real person.

No, he’s a fictional Dahl creation; the center of a parable about the need for charity and higher aspirations than greed and self-fulfillment. But as Dahl assumed the voice of an unnamed journalist/narrator, Anderson likewise wants to call attention to the fact that this is a fiction put on by artists who want to convey something to the viewer. Is that message still to be more charitable and aware of the world around you? Certainly. Yet it also seems to be about the role storytelling plays in affecting that self-awareness in viewers to be better. After all, the players and film are acutely aware of you while telling their tale.

“The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar” is streaming on Netflix now.