The Most Underrated Crime Movies of the 1970s

In a decade dominated by The Godfather and The French Connection, some major crime movies went under-reported.

When you consider the evidence, the 1970s was the greatest crime movie period since the 1930s. Maybe it’s because of the grim film stock, but those 10 years were so filled with the criminal element even a highly-rated political journalism feature like All the President’s Men (1976) is really an investigation into indictable acts. The decade is defined by Francis Ford Coppola’s first two The Godfather movies, but those tell the story of the dons who live in compounds on Long Island. Most illicit infractions are committed on the street, and so many fall between the cracks.

Crime and gangster movies historically and consistently break boundaries in motion picture art. This is especially true when independent filmmakers muscle their way in packing something heavy. The 1970s was an experimental decade for motion pictures with wildly varied visions behind the lens. Some of these films were considered old-fashioned, others have proven to be well ahead of their time. Some were so much of their time, they went unnoticed. Here are some major criminal acts which might be missing from the blotter page.

The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight (1971)

A parody of true authenticity with street cred to burn, The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight is the ideal primer for The Godfather (1972). Author Mario Puzo was inspired by the same mafia usurpers lampooned in the film, and undoubtedly read the news stories which wound up in Jimmy Breslin’s 1968 novel. The “Gallo Wars” of the late ‘50s rocked the underworld, and inspired 1970s crime films that wanted to “go to the mattresses.” But rather than pay respect to mob’s wars of attrition, The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight plays for laughs.

Financially affronted, Baccala Family enforcer “Kid Sally” Palumbo (Jerry Orbach) orders his crew to Ocean Parkway to make the brains of capo Water Buffalo (Frank Campanella) look like “lobster eggs in Fra Diavolo sauce.” After a series of felonious mishaps, they finally “change the channel on Baccala from living to dead,” when he dies of unnatural causes, at least in crime circles. Directed by TV veteran James Gladstone, the film adaptation is too broad to be as funny as the book, but it is infectious. Robert De Niro was so immersed in his role as Sicilian-born kleptomaniac Mario Trantino, who fills his pockets with American chocolate bars because he ate nothing but “chipmunks and dandelions” in Catanza, he was arrested on a shoplifting charge, according to Hal Erickson’s Any Resemblance to Actual Persons.

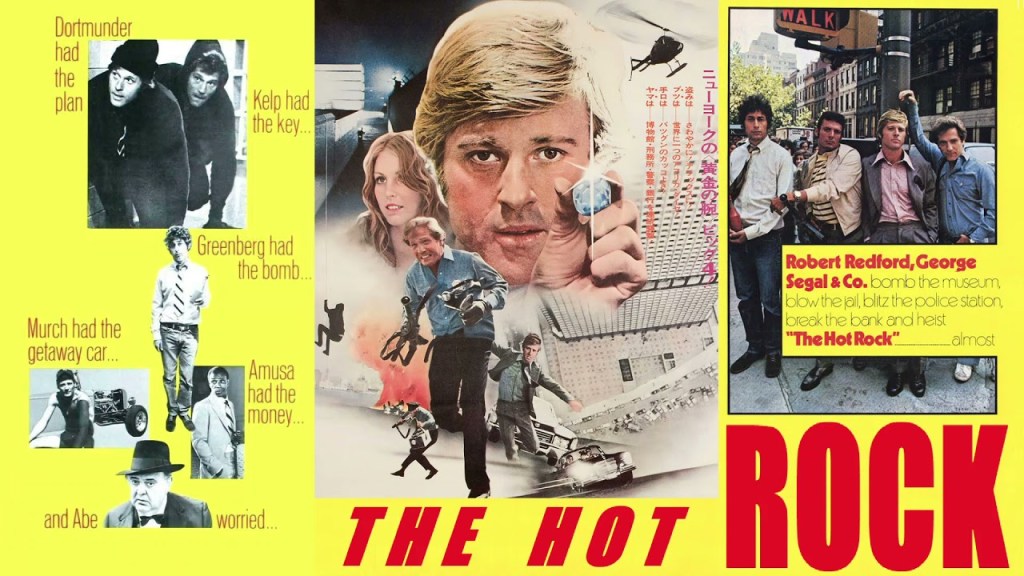

The Hot Rock (1972)

The Hot Rock shows incompetent thieves pull four successful jewel heists. It would be impressive if they weren’t always stealing the same gem: The Sahara Stone, a priceless diamond claimed by two separate African nations on loan for display at the Brooklyn Museum. Robert Redford’s John Dortmunder, newly out of prison but never going straight because his “heart wouldn’t be in it,” is the brains of the outfit. His brother-in-law Andy Kelp (George Segal) thinks from the other end but gets the job. Allan Greenberg (Paul Sand), the world’s greatest lock-picker, is all thumbs. Ambassador Dr. Amusa (Moses Gunn) wants the crown jewel stolen and returned to its ancestral home for a set price. At least that’s the plan. Costs, tensions, and hilarity soar as the crooks cook the book.

Based on Donald E. Westlake’s novel, The Hot Rock, screenwriter William Goldman and director Peter Yates polish the uncut stone, consolidating characters, and shaving robbery attempts for a tight telling of some loose canon. Circumstances subvert genre expectations as fast as Miasmo (Lynne Gordon) can say “Afghanistan banana stand.” The biggest thief is Zero Mostel, whose shyster lawyer character Abe Greenberg doesn’t keep the diamond but steals the film.

The Valachi Papers (1972)

The outside world would know nothing about the mafia if it weren’t for the 1963 testimony of the real-life Joseph Valachi. Starring Charles Bronson as the man whose name is synonymous with the word “rat” in some circles, The Valachi Papers shows why. Valachi is a standup guy who’d never think of breaking omerta, the mob’s code of silence. Don Vito Genovese (Lino Ventura) orders a prison execution before the jailed enforcer gets the chance. Nothing packs you running to the Justice Department faster than a shiv in the shower.

The role is an artistic high for Bronson, giving his most versatile performance, capturing Valachi as young, middle-aged, and old strictly through hair color and body language. He says more in silence than dialogue. The film jump-started a new career for the former supporting actor. Directed by Terence Young, produced by Dino De Laurentiis, and based on Peter Maas’ best-selling book, The Valachi Papers bombed at the box office because it came out too soon after The Godfather, and was compared unfavorably. Seen from a distance, it is a riveting historical reenactment without any frills. Let me burn like a card of a saint if I’m not telling the truth.

Across 110th Street (1972)

Director Barry Shear’s Across 110th Street is Hollywood’s first all handheld-camera-shot feature film. It is apparent in the realism, and imperative to the action, bringing intimate urgency and a documentary feel to an already realistic movie. Based on Wally Ferris’ book, the alleged blaxploitation flick is a masterpiece of crime cinema, mob rule, and urban planning. Cutting across the north end of Central Park, 110th St. is the dividing line to Harlem. In the late 1960s when the film is set, everyone who crosses above is squeezed by either the cops or the mob, or between them.

The film starts when three Black gangsters, two of them in cop uniforms, steal numbers money from Nick D’Salvio’s (Anthony Franciosa) mob family, killing two cops, two mafia button-men, and associates of the Harlem syndicate run by “Doc” Johnson (Richard Ward). It sparks a gang war that pits gangs against cops, and generations against the culture. Anyone not on the make is on the take. Anthony Quinn’s Captain Mattelli is one of the veteran actor’s most expertly villainous roles, drowning in corruption from both sides. Bobby Womack’s title track sets the beat so naturally, Quentin Tarantino timed it to bookmark Jackie Brown.

Save the Tiger (1973)

As a crime, arson is usually a guest player. When a restaurant begs to be torched in Goodfellas, or some cars in a lot in Lodi, NJ, it is usually to send a message. In director John G. Avildsen’s Save the Tiger, it is the message. The picture is a slow burn that leaves scars. A major felony is committed by minor players who should stick to white collar crimes and stylistic misdemeanors. Jack Lemmon’s Harry Stoner co-owns an LA fashion label at the end of its runway. He and his business partner Phil Greene (Jack Gilford) kept the brand alive by “inventing a new kind of arithmetic” for accounting. The government calls it fraud.

Convinced their new line is a winner, Stoner schemes to burn a warehouse for $100,000 in insurance money to cover the rollout. The plan is as elaborate as any heist film, and the crew are as complicated as the most twisted cinematic rogues’ gallery. The arsonist has a penchant for Swedish sexploitation flicks, the company designer is a pretentious hack, and Gilford’s Greene is so committed to his employees, every sentence is a character study. Lemmon won an Academy Award for Best Actor for this multi-layered role, but the film is under-discussed.

Badlands (1973)

Now veteran actors, Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek exemplify the pinnacle of their art. Terrence Malick’s Badlands makes you wonder if they didn’t come into the field fully formed. Sheen’s James Dean-idolizing generation reevaluated itself after the 1958 killing spree of the perennially young and lethally charismatic Charles Starkweather, the unspoken basis for the Kit Charruthers character whom Sheen plays. The youthful “rebel without a cause” found something worth killing for in Caril Ann Fugate, and Spacek’s Holly Sargis redeems that faith in her unofficial portrayal of Fugate in the film.

Kit and Holly are the ‘70s version of Natural Born Killers’ Mickey and Mallory. Sheen’s Kit is trigger-happy but introspective. Spacek’s Holly is emotionally stunted. When Kit shoots her father, played by Warren Oates, she sees a life-altering convenience and becomes a willing accomplice. Their mutual societal disconnect bonds them, and justifies the rising body count. But writer-director Malick doesn’t turn Kit into a manipulating sociopath, and Holly is no vapid baton-twirler. They are not romanticized like the criminal couple in Bonnie and Clyde. They are lonely travelers sharing a ride to something better, and getting bored on the way. Badlands is a road movie driven slowly off a cliff, a hard task on the flat fields of the badlands of Montana.

The Mack (1973)

Director Michael Campus’ The Mack is stone-cold-blooded truth masquerading as a street hustle. “Being rich and Black means something,” John “Goldie” Mickens (Max Julien) schools his neighborhood-reforming brother, Olinga (Roger E. Mosley). “Being poor and Black don’t mean shit.” Pushed as a blaxploitation film, Robert Poole’s screenplay spins the genre into an unrelenting dance through crime, corruption, prostitution, and evolutionary style. In the film, Goldie lets the women who work for him pick out his clothes, cars, and outer cool. To the neighborhood kids, the ex-convict and rising pimp is a hero, and he wants each of them to grow up to be doctors or lawyers. Goldie doesn’t want them even thinking of doing what he does. He’s got enough competition.

Goldie is ruthless, bold, and inventive. He deals with rats with ingenious gangster flair. The Mack is blindingly authentic, even casting Frank Ward, a pimp kingpin at the time, for street cred and turf protection. Much of the street workers and homeless in the film are just recreating their regular routines. Richard Pryor’s Slim is often heralded as comic relief, but check the “track star” scene. Slim is as scared as he is angry, nakedly laying out everything at stake when you’re The Mack.

Dillinger (1973)

John Millius’ Dillinger is a throwback and exploitation version of Bonnie and Clyde (1967) in all the best ways possible. Made at Roger Corman’s “school for filmmakers,” American International Pictures, Milius’ directorial debut matches the tightest budget to the poorest realities of the worst of the Great Depression. Audiences sided with gangsters during the lean years Dillinger is set, and Warren Oates plays the bank robber John Dillinger with assuring winks, cynical self-confidence, and fast fingers.

Most of all, Oates revels in the dangerous fun in robbing banks, the glint in his eye that shows an innocent bystander he came this close to being misidentified and shot. Dillinger is never outwardly gleeful, but the thrill of each escape plays out dramatically in his face. Ben Johnson’s FBI agent Melvin Purvis wants to break that face and lets everyone know it. It’s hard to tell the anti-hero from the villain. The line further blurs when Dillinger brazenly goes out on the town with Billie Frechette (Michelle Phillips), or flies off the handle at Baby Face Nelson (Richard Dreyfuss) for reckless gunplay. Dillinger saves its recklessness for the recreation of the raid on the Little Bohemia lodge. There’s enough carnage for three movies in that scene.

The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974)

For New Yorkers, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three tapped into a persistent sub-urban terror to rival the daily threat of exploding manhole covers: a mass transit delay. Robbers hijack a subway car loaded with passengers, demand $1 million ransom, and set their watches for an hour. Walter Matthau plays Transit Authority Police Lt. Zachary Garber like the entire world gives him an annoying itch. Mr. Blue (Robert Shaw of Jaws) is a disciplined mastermind whose planning runs from the color-coded aliases which influenced Quentin Taratino’s Reservoir Dogs, to an electrifying exit strategy. Mr. Grey (Héctor Elizondo) nurses an itchy trigger finger for trouble.

Director Joseph Sargent skips backstory for forward action and a plot that twists faster than an express train hitting a stream of green lights. The crime is so brazen, and the location so public, the audience is as baffled as the cops on how the gang could pull this off until everything derails. Never underestimate a motorman. As Mr. Green (Martin Balsam) shows, they are nothing to sneeze at. Taking of Pelham One Two Three turns up the gas on the suspense and gallows humor until the very last image freezes over the credits.

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974)

When Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia begins, Warren Oates’ Bennie seems an unlikely prospect to carry out a terminal contract. He learns fast on the job. Bennie is more than a one-man wild bunch by the time of completion though; he is a Sam Peckinpah icon. When the film came out, critics hated it with the same venomous outrage and disgust reserved for Alfredo Garcia.

At the start, Bennie is playing piano in a Mexican brothel. He’s not important and certainly no killer. But after overhearing how much money El Jefe (Emilio Fernandez) offers for proof of the death of the man who got his daughter pregnant, Bennie stumbles on a plan to collect the bounty without killing anyone. His lover, Elita (Isela Vega), tells him Alfredo is already dead. Bennie just has to dig him up, sever the head, deliver it, and pick up the cash. In a Peckinpah movie that’s as simple as gold-prospecting in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. Gig Young’s character calls himself Fred C. Dobbs, whose head is cut off in that John Huston classic. And Bennie expects he’ll be just as successful at severing heads from necks. But then, Bennie never dreamed he’d like the head, whom he comes to call “Al.”

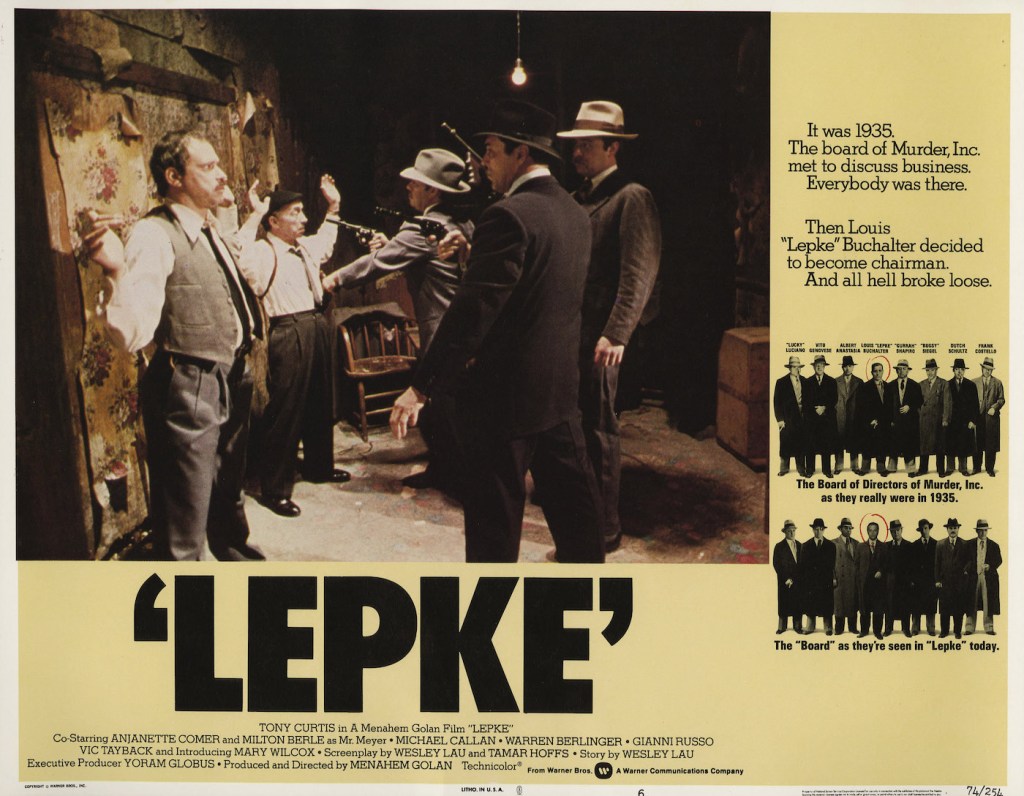

Lepke (1975)

Directed by Menahem Golan, Lepke is the story of a legendary gangster. Louie “Lepke” Buchalter invented the murder business, perfecting the trade until it got him killed in the electric chair. Tony Curtis digs into his own Bronx roots for a nuanced portrayal of a man who was as born to die as he was to kill. This is one of Curtis’ most underrated performances, possibly because it is agonizingly underplayed. Lepke is a silent threat on two legs, and Curtis brings this menacing undercurrent to every scene. It is heartbreaking to watch the overflow douse his beloved Bernice (Anjanette Comer). The lengths Lepke goes to keep business from family is murderous.

The founding CEO of “Murder Incorporated” started as a thief in his teens. The film begins after a stretch in prison leaves young Lepke wanting in on fast action. Lepke careens, in a suitably bumpy ride, through the birth of New York’s organized crime scene. Little Augie (Jack Ackerman), Lucky Luciano (Vic Tayback), and Albert Anastasia (Gianni Russo) put in appearances. While deadly serious, the film has fun with itself. One unforgettable shootout happens in a theater while a gangster movie plays onscreen.

Mikey and Nicky (1976)

Utterly inventive, Mikey and Nicky establishes high stakes immediately. John Cassavetes’ Nicky learns there’s a hit out on him for stealing from a neighborhood wise guy. He calls Mikey (Peter Falk), directing him to a phone booth, and tosses bottles wrapped in hotel towels as breadcrumbs to where he’s hiding. We know without words that Nicky is in deep shit. Mikey would be just the guy to help him lam it, if he wasn’t calling the hit man, played by Ned Beatty, from a payphone every time they stop for a Schmidt’s beer.

Frequent collaborators Cassavetes and Falk hit every desperate and convivial mark with emotional precision by mixing a specially tailored script with note-perfect improvisations. Elaine May, the third woman admitted to the Directors Guild of America, began as one half of the venerated improvisational comedy duo (Mike) Nichols and May. She encouraged impromptu realism in this low-speed chase through the connected streets of Philadelphia. Mikey and Nicky is unlike any other gangster movie. It is too intimate, almost voyeuristic. Even the business feels too personal. It was a commercial flop, with no promotion from the studio, but is a bona fide cinematic masterpiece.

The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976)

“I’m Cosmo Vitelli,” actor Ben Gazzara tells the Crazy Horse West crowd to begin The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. “I’m the owner of this joint. I choose the numbers, I direct them, I arrange them. You have any complaints, you just come to me, and I’ll throw you out on your ass.” The threat wasn’t necessary. Audiences walked out voluntarily. Critics blasted it with no silencer. Hot off the critical hit A Woman Under the Influence, pioneering independent director John Cassavetes expected goodwill. As the film points out, however, “there’s no such thing as unlimited credit.”

Vitelli dons the duds of a sophisticate and sees his peep show strip club as a suave and tasteful gentlemen’s club. Those tastes add up, and the gentleman owes money, which is “the worst sin in the world.” His port of vice and debt is Ship Ahoy, a gambling joint he supplies with his most “lovely ladies.” Loan sharks offer Vitelli a chance to roll it over if he buries some competition, a Chinese bookie. Vitelli is not really a killer, and Gazzara puts it all on the line to clear his debt. Vitelli truly loves the family he is creating with Rachel (Azizi Johari), the showgirl he is dating, and her mother Betty (Virginia Carrington). You just gotta understand though: He loves gambling more.

Assault on Precinct 13 (1976)

Mixing elements of Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo (1959) and George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), John Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 is as much a horror movie as his actual breakout in the genre, Halloween (1978). Budgeted at $100,000, the writer/director/editor/composer’s second feature is a no-frills siege thriller unlike any other. It is a spontaneous violent eruption from the moment a little girl gets blown away for complaining about a cone to the wrong ice cream truck driver.

The relentless gang, Street Thunder, then hunts the little girl’s father, who is petrified beyond the capacity to speak, and almost wordlessly seeks asylum in a nearly abandoned LA police station. It happens to be the same precinct Officer Starker (Charles Cyphers) is forced to stop by because one of his prisoners-in-transit is sick, and might be hazardously contagious. No one trapped inside the decommissioned station knows why they are under attack. Only the audience knows the LAPD shot down gang members in a cold-blood ambush. The gang does not differentiate between cops, prisoners, and innocent bystanders. Cops and criminals fight side by side. Even a little white lie can trip a man up.

Straight Time (1978)

Belgian-born filmmaker Ulu Grosbard starts Straight Time on a bittersweet note. Paroled after a vacationless six years, Dustin Hoffman’s Max Dembo is among three convicts walking out of prison gates. We hear a happy family reunion play out in Spanish behind him as Max jumps in the hatch of a pickup truck. He makes a rash U-turn just before freedom. Max wants to go straight but all he knows is crime. That’s a tough sell to legitimate gainful employment. It’s worse when his parole officer Earl (M. Emmet Walsh) is so sure Max is going to revert, he forces his hand. Earl is left humiliated, locked bare-ass on a bridge with his own cuffs.

Eddie Bunker, who wrote No Beast So Fierce, which the film is based on, did time before writing and acting (He’s Mr. Blue in Reservoir Dogs). The film’s authenticity confirms this. Theresa Russell as Dembo’s girlfriend Jenny, and Harry Dean Stanton as a gentle jewel heist accomplice, are fully formed. Gary Busey brings deep empathy to a caring father trying to hide a junk habit from his wife, played by Kathy Bates. Hoffman’s Max is low-key yet explosive, cool when chips are down, and crazy enough to wait a little too long.

Blue Collar (1978)

Blue Collar should be known as “the On the Waterfront of the 1970s.” Director Paul Schrader, who was screenwriter for Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, made his directorial debut in this union-busting drama. From the initial heist to the break-in appearance of the mob, Schrader studiously sidesteps genre clichés, ripping into corporate and union corruption like he’s stripping an abandoned car on the West Side Highway.

Zeke Brown (Richard Pryor), Jerry Bartowski (Harvey Keitel), and Smokey James (Yaphet Kotto) are Detroit autoworkers who have had it. Overworked, underpaid, and abused on the job, they rob the union office and find something more valuable than cash: a ledger linking the union to organized crime. They consider turning it into the cops, for about two minutes, until they figure it’s worth more than its weight in blackmail. Then it gets too heavy. What happens to the trio of crooks is as sad as it is suspenseful. Zeke gets bought out, Jerry becomes a crusading pariah, and Smokey is whacked in one of the most ingenious mob-ordered executions on celluloid. The detailing is breathtaking.