How the Real Donnie Brasco Bought a Mob Family a Reprieve from the FBI

After the events seen in the Donnie Brasco film, "The Commission" kicked the Bonanno Family out for letting Brasco in. That turned out to be a favor they couldn't refuse.

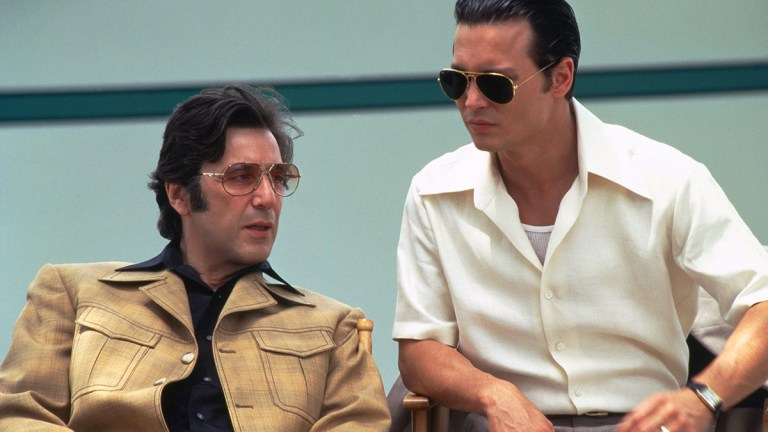

The 1997 mob movie, Donnie Brasco, celebrates its 25th anniversary this week. This is almost as long as the real-life title character has been on the run with a half-a-million-dollar contract on his head. Johnny Depp plays Joe Pistone in the movie, an undercover federal cop codenamed “Donnie Brasco.” He gets so deep into the wheels of the Brooklyn operations of the Bonanno crime family that he almost becomes a made man. Donnie is one hit away from getting straightened out, joining the official rank and file of the organization, when the FBI pulls him in from the case. The mere notion that such an embarrassing breach could occur got the Bonannos kicked out of the Five Family ruling hierarchy. It turned out to be fortunate timing when the “Mafia Commission” went down in a federal rap, but at the time, forget about it.

Written by Paul Attanasio and directed by Mike Newell, Donnie Brasco is based on the true story co-written by Pistone.

Brasco’s cover at the start of his infiltration was as a Florida jewel thief. He was a fugazi, a fake wise guy just like the diamond he turns down when asked to fence. But he was a good one. As detailed in the movie, the undercover agent fools career soldier and hitman Benjamin “Lefty Guns” Ruggiero, played by Al Pacino. Lefty takes Brasco on as his protégé, teaching him the codes and making him shave his mustache. The young cop then gets in good with his mentor’s boss, capo Dominick “Sonny Black” Napolitano (Michael Madsen), moving up in the ranks until he doesn’t know if he’s a fed or a friend of a friend.

Organized crime does not like loose ends, and cut dysfunctional family ties over such confusion. Permanently.

How to Fix a Leak

Donnie Brasco plays Pistone’s sense of duty off the criminal world’s emphasis on loyalty, with the film becoming a character study into the crevice between the two worlds of crime and punishment. It thereby shows the early unraveling of the unspoken bonds of illicit business.

Omerta isn’t just some macho street code; it is a crucial security measure. Silence and secrecy keep the operations running smoothly. When the FBI tells Sonny Black the man he knew as Donnie Brasco was an agent all along, it is a threat. The agency is insinuating cops can infiltrate the mob at will. On the surface, the feds do this to instill paranoia, hoping Sonny and Lefty will turn informant before they are taken care of internally. The two made men know they could be killed just for letting Donnie sit at their table, whether or not he takes off his surveillance-rigged shoes.

The FBI’s coercive tactics also triggered death warrants. On Aug. 17, 1981, the mob called for Sonny Black Napolitano. He gave his jewelry and the keys to his apartment to a bartender friend, and told him to look after his pigeons. Napolitano was picked up at a steakhouse in Bay Ridge, taken to Staten Island, and shot in a basement by Ronald Filocomo and Frank “Curly” Lino, according to later testimony. Anthony Mirra, the man who brought Pistone to the family, was also killed. It was part of an ongoing power struggle within the Bonanno Family.

Lefty Ruggiero was arrested within days of being notified of Pistone’s active duty status. He honestly didn’t believe Brasco was a cop. He assured his lawyer that Pistone would not testify against him. The undercover officer’s testimony helped get Ruggiero convicted and sentenced to 15 years. He served 11 years and was released when he was diagnosed with lung and testicular cancer. Lefty was a standup guy. He never informed on anyone. He was forgiven for being fooled by Pistone, and the contract on him for the miscalculation was lifted. Ruggiero died on Nov. 24, 1994 of natural causes. He was 68 years old.

The Bonanno Family was not forgiven. They were already under watch by the national high council as a rogue outfit over drug trafficking. The leak ended discussions. Pistone gave the FBI inside dope on the big players, and which rackets they ran. His testimony led to over 100 federal convictions.

More damagingly, Pistone confirmed the existence of “the Commission.” It was a public embarrassment.

The Bonanno Family, one of the first of the Five New York Families on the Commission, were the first to be kicked off. They were also the first to get back on their feet after “The Commission Trial.”

Bonanno Family History

The Bonanno Family was always a rebellious unit within the commission. It was founded and named after Joseph Bonanno, who was at the time the youngest of the bosses of the Five Families at 26 years old in 1931. According to A Man of Honor: The Autobiography of Joseph Bonanno, the first memoir ever written by a mafia father, the family can be traced back to the early 1880s in the town of Castellammare del Golfo, located in the Province of Trapani, Sicily.

In the “Roaring Twenties” of the 20th century, top members of the Bonanno, Bonventre, and Magaddino Sicilian mafia families relocated to Williamsburg, Brooklyn, forming “the Castellammarese clan.” Backing Salvatore Maranzano, who wanted to take control over New York’s underworld, the gang had street fights with the Buccellato clan and hijacked trucks of liquor that belonged to Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria. By 1927, the turf battle became known as “the Castellammarese War.”

Knowing they were unhappy, Maranzano made deals with Joe the Boss’ “Young Turks,” rising stars Charles “Lucky” Luciano, Vito Genovese, Frank Costello, Tommy Gagliano, Tommy Lucchese, and Gaetano Reina from the Bronx. On April 15, 1931, Masseria was murdered. Maranzano declared himself “Boss of Bosses,” and reorganized New York’s Italian American gangs into the Five Families, headed by Luciano, Joseph Profaci, Tommy Gagliano, Vincent Mangano, and his own.

Opposed to Luciano’s partnership with Meyer Lansky and Benjamin Siegel, Maranzana hired Vincent “Mad Dog” Coll to eliminate the progressive upstart. On Sept. 10, 1931, crime’s new chief executive was executed by Jewish gangsters on the orders of Luciano, who established “The Commission.” Maranzano’s underboss Joseph Bonanno took the fifth seat.

In the early 1960s, the Bonanno Family went into a civil war, called the “Banana Split” by New York papers. Joe Bonanno went into hiding, suffered a heart attack, and retired in 1968. After continued unrest in the ranks, the Commission ultimately stepped in. They named Paul Sciacca as boss, he was replaced by Natale “Joe Diamonds” Evola, who died of natural causes leaving Phillip “Rusty” Rastelli as head of the family in 1973.

Rastelli put Carmine Galante in charge of refining the Bonanno Family’s drug trafficking operations. Galante ordered hits on eight members of the Genovese family for trying to muscle in on the exclusive action. Galante was shot dead by three men in Joe and Mary’s Restaurant in Bushwick, Brooklyn on July 12, 1979. Family capos Phillip Giaccone, Alphonse “Sonny Red” Indelicato, and Dominick “Big Trin” Trinchera plotted to overthrow Rastelli, who ordered “Sonny Black” Napolitano, and future Boss Joseph “Big Joe” Massino, to get rid of them. One of the gunmen was “Lefty Guns” Ruggiero.

This is where Donnie Brasco begins.

The Commission removed the Bonanno Family from the panel shortly after the movie fades. They were out of the proceedings when the federal government pressed charges in the “Mafia Commission Trial.”

The Commission Trial

Revealed in February 1985, the FBI and U.S. attorneys for the Southern District of New York built their “Mafia Commission” indictments on five years of investigations, 171 court-authorized wiretaps and bugs, and more than 200 federal agents. Among the witnesses were some high-ranking Mafia figures, as well as Joseph Pistone.

The original indictment contained nine defendants, including four bosses: Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno of the Genovese Family, Anthony “Tony Ducks” Corallo of the Lucchese outfit, and Paul “Big Paul” Castellano of the Gambinos, who was murdered on Dec. 16, 1985 before the trial began. Rastelli was on the original indictment but removed after the court learned the Bonanno Family were kicked off the Commission. The families would never admit there was a Commission, but all agreed the Bonanno Family was not on it. Rastelli was later indicted on separate labor racketeering charges.

Carmine “Junior” Persico was added to the indictment. He had been convicted of being the Colombo Family boss earlier that year. He represented himself, and claimed he was facing double jeopardy because that case was still being appealed. Federal Judge Richard Owen denied his request. Persico argued that, just because the government spun the fiction that the mafia was a criminal enterprise, didn’t mean it could be presented that way to the jury as absolute truth. Judge Owen denied. The defense asked the trial be delayed due to the excessive pretrial publicity. Judge Owen denied that request as well. He gave prospective jurors a quiz on their knowledge of organized crime, including whether they could identify such figures as Al Capone, Vito Genovese, and Lucky Luciano.

The indictments were handed down on Feb. 25, 1985. On July 1, the accused crime leaders pleaded not guilty. The worst damage to the organization was probably done by former Cleveland underboss Angelo Lonardo, one of the highest-ranking Mafia figures to ever become a government witness. He testified the bosses of the five New York families controlled the entire national Mafia through the Commission. He identified the five New York families as Genovese, Gambino, Lucchese, Colombo and Bonanno.

On Nov. 17, 1986, the federal appeals court ruled Persico, his son Alphonse, and six others were guilty of being leaders of the Colombo family, and Persico received a 39-year sentence. The Commission Trial jury’s verdict came down on Nov. 19. All eight defendants were found guilty of racketeering, conspiracy, and operating a Commission that ruled the mafia throughout the U.S. Sentencing was set for Jan. 13, 1987.

Judge Richard Owen said he was not only sentencing the men, but the institution of “overall crime” itself. Each man was facing a minimum of 40 years in prison. He sentenced them all to 100 years, explained they would be eligible for parole after 10 years, and recommended parole be denied for all of them.

Aftermath and Reinstatement

Rastelli ruled the Bonanno Family from inside prison until his death in 1991. Joseph C. Massino took the top spot in 1993. The Bonanno Family’s ranks and power sank so dramatically by the early 1990s, the FBI disbanded the squad who was surveilling their operations. Because of this lapse, the Bonanno mob rose to become one of the most powerful groups in New York. Massino, who served a prison term for racketeering and extortion, learned from the mistakes of the bosses who attracted attention to themselves. He opened the books, increasing the number of made soldiers and capos to 110. Besides one crew of Sicilian-born members, known as Zips, who ran their heroin operations, the family concentrated on traditional rackets like money laundering and loan sharking.

John Gotti, boss of the Gambino crime family, helped the Bonanno Family regain their seat on The Commission. But the family claimed one more dubious milestone in the history of the American Mafia: Convicted in a RICO case and facing the death penalty in a separate murder trial, Massino became the first boss of one of the Five Families to turn state’s evidence in 2004.

Donnie Brasco is streaming now on Netflix.