The Original Gladiator 2 Saw Russell Crowe Return as an Immortal Time Traveler

We examine the road to Gladiator II not taken in a 2001 screenplay by Nick Cave. Written at the behest of Russell Crowe, it "sorted out" Maximus being dead by beginning in the afterlife and ending with America's Vietnam War...

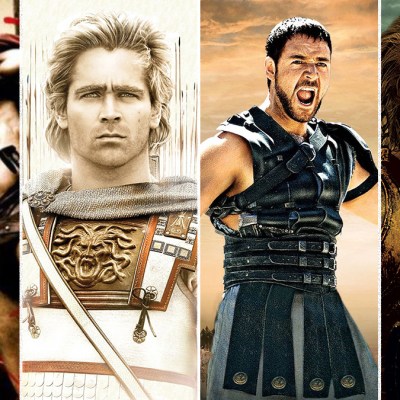

When audiences return to Rome’s Colosseum for Ridley Scott’s Gladiator II they will surely be entertained by the spectacle of warriors fighting for their lives—and for the fickle attention spans of Roman emperors and an angry public. It’s WWE 200 A.D.. Much like its Oscar-winning predecessor Gladiator, Gladiator II is a story of an unlikely hero from humble beginnings who wants to rain bloody vengeance upon an empire’s elite. In that regard, Paul Mescal’s Lucius is not so different from Maximus, the titular gladiator played by Russell Crowe. But what many fans might not know is that Maximus was almost Gladiator II’s main character…. despite his death at the end of the first movie.

There were indeed several attempts to get a sequel to the 2000 blockbuster made over the years, but one script gained special notoriety for its religious themes, which were characteristic of Scott’s other output post-Gladiator. But it took that subject matter to a heightened and supernatural extreme. Yes, there is a completed Gladiator II script that continued Maximus’ quest for revenge beyond his own death, beyond ancient Rome, and against the most unlikely adversary of all… Jesus Christ.

And it all began with a phone call between Russell Crowe and fellow Aussie and friend, rock singer Nick Cave.

Nick Cave Goes to Rome

Cave is most known for fronting Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, whose biggest hit song is “Red Right Hand,” a dark, sexy tune familiar to anyone who loves the Scream franchise, The X-Files, or Peaky Blinders. Cave’s songs were often full of Old Testament fire and brimstone, and his script for The Proposition, a 2005 gory neo-Western starring Guy Pearce and John Hurt as bounty hunters, was no different.

Around that same time, Scott was working on a Gladiator sequel with original screenwriter John Logan that had nothing to do with Maximus or even gladiators. Crowe, however, was eager to present the director with a sequel he could still star in. The Academy Award-winning actor was so taken with Cave’s writing he enlisted the songwriter to “sort out” the little matter of Maximus’ death and come up with a new fight for the resurrected Roman general.

Maximus Is… the Christ-Killer

Christ-Killer, the 2001 screenplay’s working title, began with Maximus waking up in a dark purgatory on the shores of a black ocean where the dying Roman gods fight one another. It is these petty deities who also tell Maximus that he must kill Hephaestos. While in the Roman-Greco tradition Hephaestos is the God of Fire and Blacksmithing, he has lately been spreading the troublesome gospel of a new monotheistic Christian God. So Hephaestos (and Christianity) must die if Maximus is to be reunited with his wife in the wheatfields of Elysium, where the sun always shines and Lisa Gerrard forever warbles. If that sounds bizarre already, wait until you and Maximus learn that his wife was able to plead with the gods to restore their seven-year-old son back to life!

This all sets up Maximus returning to Ancient Rome 20 years after his death in the arena. There he reunites with his best friend Juba (Djimon Hounsou would ideally reprise his role) and his son Marius, now a grown man and Christian convert, at a time when Rome was executing followers of the new religion. Maximus gets embroiled in the war between the persecuted Christians and Roman authorities and faces off against Lucius, now a corrupt leader like his Uncle Commodus (Joaquin Phoenix). Lucius is especially determined to stamp out Christianity after his mother Lucilla (Connie Nielsen) was stoned to death for her new religious fervor.

While Maximus, disappointingly, never actually crosses swords with Jesus, he does double-cross the Greco-Roman gods by training Marius and the Christians as soldiers to rebel against the Roman Empire, and thus the old gods. Because Maximus’ choice allows the teaching of Jesus to spread—and especially because Maximus trained the Christians to use violence instead of peaceful resistance—Maximus is forbidden to return to Elysium and reunite with his wife. Instead he is “gifted” immortal life as an eternal warrior that will forever doom humanity by encouraging warfare.

This concept is visualized literally with a frenetic montage of Maximus leading an army not only in Ancient Rome, but Persia during the Crusades, among tanks in World War I, and into the jungles of Vietnam. The final scene leaves Maximus sitting at a head of a meeting table in the Pentagon, hunched over a laptop and planning a present-day war.

Why It Didn’t Get Made

“Don’t like it, mate,” Crowe reportedly told Cave, who harbors no regrets.

Speaking with Marc Maron’s WTF podcast, Cave called the rejected story “a stone cold masterpiece,” made with wild creative abandon because he was so certain that the screenplay would never actually get made. Cave continued to poke fun at his Gladiator experience, culminating in the outlandish music video for “Heathen Child” from his side project Grinderman, which features Cave and company dressed as gladiators, dancing over explosions.

As utterly anti-commercial as Cave’s script was, one could see how it would fit alongside Scott’s work in his post-Gladiator period, which seemed increasingly concerned with confronting faith. The director has described himself as an atheist, but his post-Gladiator output seems to be less against spirituality than against corrupt organized religion as films like Kingdom of Heaven, Robin Hood, and Exodus: Gods and Kings suggest. Prometheus and Alien: Covenant similarly place spiritual faith as equal to scientific knowledge, perhaps even marking it as more important. Those recent Alien movies also depict the divine originating away from human-adjacent creatures, whether it’s off-world Engineers or the incalculable intelligence of a sentient android.

Scott himself recently called the Christ-Killer script “bloody silly,” but Gladiator II does share some distant DNA with it. Cave’s script also revisited the Roman Colosseum with a naval battle in the flooded arena, where crocodiles replaced the final movie’s sharks. Scott also gives a more overt nod to one Cave idea he genuinely enjoyed: the moonlit shores of the river Styx where Lucius dreams of his dead wife’s soul. This provides a new, darker vision of the afterlife.

As epic as Maximus versus Jesus might have been, for all the bombast and pageantry a Ridley Scott sword and sandals already drama contains, perhaps Scott’s depiction of eternity doesn’t need its own competing storyline, with a large cast of gods and audience-fave characters like Maximus transformed into pawns for an evil, unwinnable forever war.

The emotional core of the Gladiator is a simpler, more universal story of grieving warriors where brief visions of the afterlife exist to remind the hero that he must fight for the concepts that represent the best of humanity: strength and honor, family and love.