It Chapter Two: Pennywise Backstory Explained

We examine the warped Pennywise backstory in It Chapter Two, as well as in Stephen King's original It novel.

This article contains major spoilers for It Chapter Two and Stephen King’s It novel.

One thing can be said about Stephen King’s It and the multiple movies and miniseries it spawned: nothing is done in half measures. Always intended to be gargantuan in scope, the novel It took an uncharacteristically long time for King to write—about half a decade between 1981 and 1986—as he attempted to examine childhood and the scars we forget it leaves. Hence the first major cinematic telling of It being divided into two movies, with the finale alone running at nearly three hours.

Yet for all its wistful melancholy about the agonies and ecstasies of youth that are better left in the past, It Chapter Two and its source material still boils down to one thing for most folks: a scary clown named Pennywise and the monstrous things he gets up to. Technically speaking, Pennywise is not actually what It is. Rather Pennywise is just one of many forms an extraterrestrial, godlike being takes in order to lure small children into the deadlights. But just what are the deadlights, what is It, and how long have they been in Derry? It Chapter Two is vague on all those details, but by combining hints from the epic movie with some of King’s most grandiose musings in the 1,100-page book, we think we can answer your main questions about the Dancing Clown below…

Is Pennywise an Alien?

The short answer is yes. It most definitely is not from around here, nor is It even part of our own universe. While 2017’s It mostly sidestepped the science fiction elements of Pennywise in favor of the supernatural terror of an evil clown that can take the shape of whatever scares you most, 2019’s It Chapter Two dives headlong into the weirder side of King’s creation. This occurs early on when Mike (Isaiah Mutafa) spikes the drink of Bill Denbrough (James McAvoy) with a “root.”

Together, they have a trip based on Mike’s own previous experiences with Natives who live outside the borders of Derry, and therefore outside the reach of It. They reveal an ancient weapon alleged to be part of the Ritual of Chüd, which includes markings based on visions of It’s arrival to this part of the world. Appearing like a comet or asteroid, It landed on Earth at what is initially a nondescript time long ago. Later on in the film, when the Losers enter It’s Lair, they realize they’re standing in the ground zero crater of an asteroid right beneath Derry.

The novel makes it clearer. In King’s writings, there are no Native Americans who teach Mike Hanlon the Ritual of Chüd. Instead the Losers as children dabble in political incorrectness by copying what Ben read about “Indian smoke holes” in a book (it was a scene set in the ‘50s that was written in the ‘80s). Turning their clubhouse into a smoke house, they burn twigs and breathe deep the fumes that drift from them in order to jumpstart visions. Most of the Losers run coughing from the structure, but not Richie or Mike. Those two lads have visions of It’s arrival in some period after the dinosaurs died out but before the ice age or humankind’s ascendency. This is confirmed by Richie and Mike seeing giant mammal bats as big as humans, as well as birds fleeing en masse from the approach of something terrible above.

read more: It Chapter Two Easter Eggs and Reference Guide

“The clouds in the west lit with a bloom of red fire. It traced its way toward them, widening from an artery to a stream to a river of ominous color; and then, as a burning, falling object broke through the cloud cover, the wind came. It was hot and searing, smoky and suffocating. The thing in the sky was gigantic, a flaming match-head that was nearly too bright to look at… A spaceship! Richie screamed, falling to his knees and covering his eyes. Oh my God it’s a spaceship!”

Whether it was actually an asteroid or spaceship, King leaves ambiguous, but we tend to agree with director Andy Muschietti’s choice of leaning toward the former given It’s final form.

Has It Always Been in Derry?

Yes, arriving here millions of years ago, It has always been a piece of Derry, essentially turning humans into Its own livestock. It is telling in 2017’s It that Mike is introduced as a child who is reluctant to shoot a sheep in the head with a cattle gun. This is a hint of the world he lives in, where he and all of Derry’s residents are essentially cattle waiting for It to wake up and pull the trigger. Perhaps Pennywise’s biggest mistake ends up not being mercifully quick but playing with It’s food until the Losers can fight back.

The 2017 film hints at It’s previous reigns of carnage which occur roughly every 27 years. There was the Kitchner Ironworks that exploded in 1906 on Easter Sunday, killing 108 people, 88 of whom were children. This marked the end of It’s feeding frenzy that year. Then there was the time in 1929 It woke up early because the residents of Derry revealed the bloodthirsty influence of their benefactor when they collectively murdered the Bradley Gang (modeled after Bonnie and Clyde) in the streets. That unusual violent streak in Derry is It’s influence, which can be seen in the films when Henry Bowers attempts to carve his own name into Ben Hanscom’s stomach and adults look the other way while driving by, or in homophobia turning into a hate crime against Adrian Mellon (Xavier Dolan) in It Chapter Two’s opening.

In the book, the earliest recorded murders occurred in 1741 when the original Derry township vanished. Inspired by the Lost Colony of Roanoke, King writes about the Derrie Company’s original party of white settlers who moved into the area. “They were there in June of that year—a community which at that time numbered around three hundred and forty souls—but come October they were gone. The little village of wooden houses stood utterly deserted.”

Despite the lack of bodies, New Englanders and thus history assumed it was the work of an Indian massacre, but we of course know better. The 19th century is littered with similar anecdotes that Mike Hanlon uncovers, the best of which involved a crew of lumberjacks in 1879 finding the remains of another who’d “spent the winter snowed in at a camp on the Upper Kenduskeag—at the tip of what the kids still call the Barrens. There were nine of them in all, all nine hacked to pieces. Heads rolled… not to mention arms… a foot or two… and a man’s penis had been nailed to one wall of the cabin.”

When Bill and Richie finally confront It in its final form in the book, they note It smells like the Barrens. That is to say, It smells like all of Derry, the adults there have just lived with it for so long they never noticed.

When Did It Become Pennywise?

This is more ambiguous, and Andy Muschietti and It Chapter Two go a much longer way toward explaining it than Stephen King ever did. While It takes many forms in the novel, clearly It’s favorite is that of Pennywise the Dancing Clown, who is just as scary as he is supposedly endearing to children. It’s unclear when King intended for Pennywise and It to become synonymous, but the earliest incident uncovered in Derry’s history might be in 1904 when a lumberjack slaughters a dozen men at a Derry bar with an axe as revenge for the homophobic murder of his lover—which echoes what happens later to Adrian Mellon. Mike interviewed an old-timer who was there, among the dozens of other citizens who did nothing but mind their drinks, and the old man said he noticed “a comical sort of fella” in the corner.

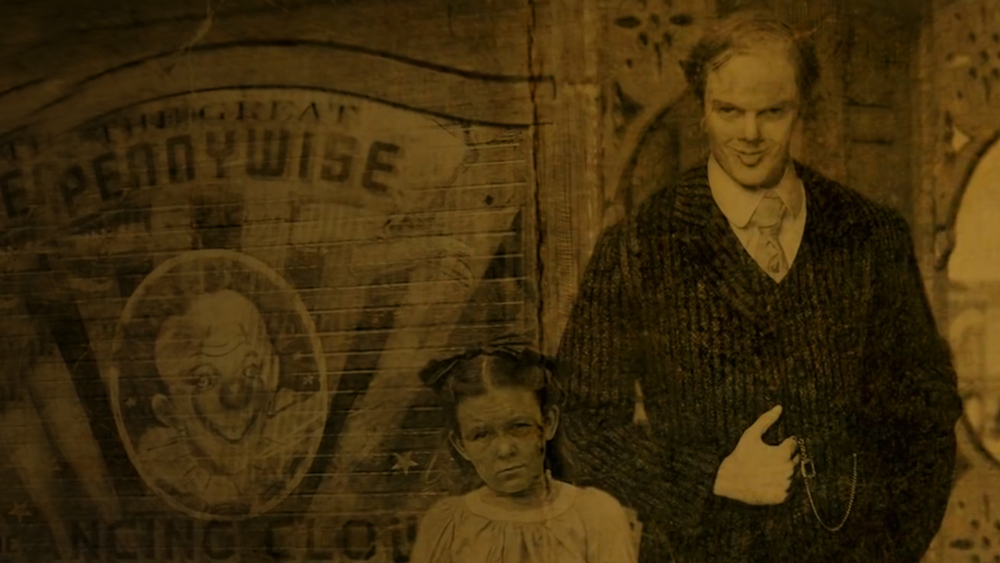

It Chapter Two more explicitly suggests Pennywise was an actual clown who may have been possessed by It, just as Henry Bowers is in the movies. This is implied when Beverly Marsh (Jessica Chastain) visits the apartment she grew up in with her abusive father. The old woman living there now says her father immigrated to the United States with $14 in his pocket before joining the circus. Bev then examines old photos that look far too ancient, even for an elderly woman in 2016. In grainy photographs from the turn of the 20th century or even earlier, we see Bill Skarsgård (who plays Pennywise) standing in front of a horse-drawn circus wagon that reads, “THE GREAT PENNYWISE, THE DANCING CLOWN.” Bev next sees a vision (or a ghost?) of the very human Pennywise mutilating his face.

Muschietti appears to be implying Pennywise was a human familiar who It corrupted and then enjoyed so much It incorporated his shape into its file cabinet of monsters. Muschietti suggested as much when I talked to him in July about It Chapter Two. During the interview, he expressed an interest in exploring “Bob Gray,” a name that isn’t uttered in either movie but is another of It’s aliases in the book.

“Everything that relates to Pennywise and Bob Gray is very cryptic, and it’s like that for a reason,” Muschietti says. “Probably the success of that character as a monster, as a villain is because of that crypticness and uncertainty that people have towards him. We don’t know exactly what he is, where he comes from, or how Bob Gray is related. Was Bob Gray a real person? Is he incarnated in that thing because Bob Gray played a clown? He knew it attracted children, so that was a perfect bait?”

We can thereby conclude that in It Chapter Two that Bob Gray was a 19th century clown (or thereabouts) in a traveling circus who made the mistake of coming to Derry. Like how It can become Beverly’s father to torment her, It often becomes Pennywise, delighting in the laughter and screams of children.

What is Pennywise’s Final Form?

The aspect that everyone most remembers from 1990’s It miniseries, besides Tim Curry, is that wacky ending where Pennywise turns into a giant, laughable spider. It Chapter Two kind of goes there with Pennywise sprouting giant spider legs, first when It is in the shape of dead Stan Uris’ head, and then again when It is Pennywise, the Giant Arachnid Clown at the end. However, it is intentionally vague if this is Pennywise’s true final form in the movie or just another menacing shape It is taking to terrify the Losers’ Club (all the better for feasting on their fear).

In the book, this is both clearer and more confusing. Yes, It’s final form is a giant spider that is written to sound more Lovecraftian than the ABC TV movie, but that really isn’t It’s true shape. Rather a spider is the closest our puny mortal minds can perceive It’s evil to be.

King writes, “Then Beverly was shrieking, clinging to Bill, as It raced down the gossamer curtain of Its webbing, a nightmare Spider from beyond time and space, a Spider from beyond the fevered imaginings of whatever inmates may live in the deepest depths of hell. No, Bill thought coldly, not a Spider either, not really, but this shape isn’t one It picked out of our minds; it’s just the closest our minds can come to (the deadlights) whatever It really is.”

Those deadlights, cosmic beams of malevolent energy that Pennywise reveals by opening his mouth in the movies, are probably the closest thing to Its true final form. The ending of the book—which gets into some cosmic weirdness that Muschietti wisely avoids—reveals that It is older than a few million or a few billion years. Indeed, It is older than our entire universe as its true form exists beyond our understanding of existence. It comes from the Macroverse, which wraps around our universe, and It is a sibling to a giant space turtle called Maturin, who created our universe by accident when he had a tummy ache and barfed it out.

Yep, as It Chapter Two jokes, Bill Denbrough has a problem with endings. And at the end of Stephen King’s It, Bill Denbrough enacts the Ritual of Chüd, which on the page causes Bill as a child in 1958 and then again as an adult in 1985 to enter into a psychic battle of wills with It by staring into the Spider’s deadlight eyes. This transposes his consciousness across the universe and drags him to its limits. It is beyond the barriers of our universe where It lives in the greater Macroverse as floating forms of light. Deadlights.

Says Pennywise’s psychic link to Bill as he floats through the cosmos in the book, “Little Friend! wait until you break through to where I am! wait for the deadlights! you’ll look and you’ll go mad… but you’ll live… and live… and live… inside them… inside Me…”

read more: The Best Stephen King Movies

So in a nutshell, Pennywise/It’s true form is floating balls of light out in space, and if you look at them in their true form, your mind will live eternally in It’s thrall (this is what happens to Bill’s wife Audra in the book). Luckily, Bill is saved from such a fate as an adult when Richie also stares into the deadlights and then completes the Ritual of Chüd on behalf of Bill reeling him back to our world where It can be destroyed in its physical form of a giant spider… as can It’s heirs.

Yes, one last morsel for those who don’t want to read 1,100 pages of clowning. Technically, It might be a she who is pregnant when the Losers confront the Spider in 1985 with an egg sack of offspring about to pop. Ben Hanscom winds up terminating these little spider critters with extreme prejudice.

You may be wondering then, what again is It’s true form? Floating balls of light? A giant spider? A pitiful eight-legged clown who the Losers stomp on at the end of It Chapter Two? I suppose the good thing about Stephen King’s writing is it’s all so verbose that you have multiple choices!

So there you have the backstory of It, Pennywise, and the giant freakin’ Spider. Any questions?

It Chapter Two is in theaters now.

David Crow is the Film Section Editor at Den of Geek. He’s also a member of the Online Film Critics Society. Read more of his work here. You can follow him on Twitter @DCrowsNest.