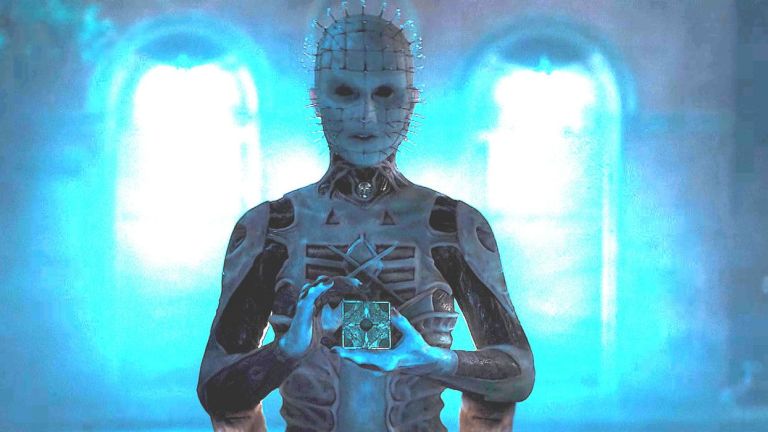

Hellraiser: Are Pinhead and the Cenobites Demons or Angels?

The Hell Priest of Clive Barker’s Hellraiser may not have been heaven sent, but Pinhead has always brought a perverse taste of paradise.

Director David Bruckner’s Hellraiser reboot just made a big and gooey splash on Hulu. In its messy aftermath, folks are discovering the old burning questions fans have long had about the world of Cenobites and chains: Are these creatures, created by Clive Barker, demons out of the actual biblical Hell, and is their menacing puzzle box (aka the Lament Configuration) a gateway to the whole of damnation, debasement, and diabolical disfiguration? Or is it something more… delicious? The original Pinhead in 1987 teased that they are “demons to some, angels to others.” So can these monsters represent a more heavenly glow? (And is that any better?)

Whenever a mortal encounters an angel in the Bible, Old Testament or New, the first sentence the angel heralds is: “Be not afraid.” Representatives of God on Earth are not easy on the eye, and very quick on the draw. They are not the cute cherubs of Sunday school, and stained-glass windows will never do them justice. In the Book of Exodus, angels are assigned the task of killing first-born sons, conjuring plagues, locusts, and smiting with all their might. Demons are supposed to be more frightening still, but it is difficult to imagine they possess the savagery because, in the Bible, spoiler alert, they fight for the losing side.

The Original, Godless Origins of the Cenobites

In Barker’s novella The Hellbound Heart, and the original ‘87 Hellraiser it inspired, the Cenobites are similarly ambiguous, although they claim to have a higher success ratio of satisfied customers.

“Explorers in the further regions of experience,” the Priest of the Order of the Gash, and the Pontifex of Leviathan, but best known as Pinhead (Doug Bradley), explains to Kirsty Cotton (Ashley Laurence), the girl who cracks the codex on the Lament Configuration in Hellraiser and gets a heaping dose of lifetime trauma for her troubles. “Demons to some, angels to others.”

But amongst themselves, Cenobites are highly committed roleplaying fetishists, with a portal to the best damned sex club in known and unknown worlds. Some may call it Hell, others can find heaven at a place like Cellblock 28, the hard-hitting Little West 12th Street S&M club which shaped the film’s eternal afterlife party.

“Hell” itself, as it’s never actually called by the Cenobites in the original movie, is the ultimate Hellfire Club: a dimension with a massive labyrinth of debauched delights and a daunting dance floor, with décor inspired by M.C. Escher, and a DJ who scratches grooves into the soul. To get past the velvet ropes, Cenobites usually have uniquely identifying body piercings, or signifying mutilations. All the devotees are devoted to the punk/BDSM fashion ethos of the ‘80s, and uniform themselves in black leather religious vestments or butcher’s aprons carved from endangered meats.

In the earliest works, the Cenobites are not evil; they are amoral. They bear neither good nor ill will toward their victims, and are as indifferent as a natural disaster. Tears are a waste. The Cenobites deify supernatural hedonism. The ultimate pleasure comes from expanding pain in others until they breach sensory overload, or to endure tortures which defy physics. As the franchise grew, so did the Cenobites’ fall into a more traditionally evil philosophy.

Hellraiser was Barker’s directorial debut, taking the reins after being disappointed by adaptations of his Underworld in 1985 and Rawhead Rex in 1986. Barker is one of the godfathers of splatterpunk, publishing the short horror collections Books of Blood from 1984 to 1985. These included the story “The Forbidden,” which became the classic Candyman movie in 1992. Splatterpunk authors like Baker and Poppy Z. Brite toppled boundaries in normative horror literature.

The low-budget, indie Hellraiser is renowned as the sick horror flick with the S&M demons. The plot follows Frank Cotton (Sean Chapman), who tests his body with dangerous drugs and flirts with perdition with risky sex. He buys a mysterious talisman on the promise it will fulfill his insatiable lust. The box has “always been his,” he is told on purchase at a buyers beware bazaar.

Upon puzzling through geometrically gravitational impossibilities, Frank summons the Order of the Gash, and things get bizarre. “I thought I’d gone to the limits. I hadn’t,” he later says after the flesh has been peeled from his bones. “The Cenobites gave me an experience beyond the limits. Pain and pleasure, indivisible.”

The exchange is similar to selling the soul in its contractually binding forethought. In the novella, Frank confirms his desires to the Cenobites, agreeing to surrender control to gain enlightenment, and with full knowledge that once you submit to the Order of the Gash, it cannot be reversed. After Frank achieves overload, his brother Larry (Andrew Robinson) and Larry’s wife Julia (Clare Higgins), who had an affair with Frank, take over the house. If Hellraiser were a haunted house movie, it would be sex, rather than a poltergeist, which torments the home.

The Cenobites are extra-dimensional beings who enter Earth’s reality through a schism in time and space which can be reached through ancient artifacts like the puzzle box. There is no specific reference which marks them as aligned with Judeo-Christian religions, and the Eastern symbology is mixed. Cenobite mythology combines a multitude of sources, but is an invention. The original three “male” Cenobites (at least onscreen) are Pinhead, Chatterer, and Butterball; Deep Throat is the only original “female” Cenobite. But the designations came after the fact. The Cenobites are neutral on the page, and their genders are indefinable.

Pinhead for a New Age

Jamie Clayton plays Pinhead in the new movie, and some uncourageous explorers of the outer limits of experience are crying foul. They forget The Priest in The Hellbound Heart, merely called Lead Cenobite on the page, is androgynous. This corresponds to Elphias Levi’s 1854 depiction of the Sabbatic Goat Mendes, which Aleister Crowley connected with Satan. The figure is better known as Baphomet, and represents the “Divine Androgyne.”

Sanctified as a weapon at the Inquisition of the Knights Templar, the Gnostics and Templars were divided on whether Baphomet was a demon or deity. Ambiguity knows no bounds in the mysteries of arcane knowledge.

Barker’s novella, The Hellbound Heart, describes the Lead Cenobite’s skull as being adorned with glistening jewels, having decorated fingernails, and that “its voice was light and breathy—the voice of an excited girl. Every inch of its head had been tattooed with an intricate grid, and at every intersection of horizontal and vertical axes a jeweled pin driven through to the bone. Its tongue was similarly decorated.”

Biblical angels are also neither male nor female, though they only make house calls on God’s orders. Cenobites must be summoned, but not petitioned by pious prayer. They crave otherworldly sensual experience beyond the boundaries of pain and pleasure. Their quest is neither demonic nor holy, Cenobites answer to need with the assumption that everytime the Lament Configuration is solved, there is someone who wishes to play (although not necessarily the person who solves the puzzle).

“It is not hands that call us,” the Hell Priest says in Hellbound: Hellraiser II (1988), “It is desire.” The Cenobites achieved selfhood through perfect pleasure, degradation and pain, in direct offense to the world on the other side of the box. But not to those they visit. They are not angels of death.

The original movie’s heroine, Kirsty Cotton, is an innocent. She does not know what she is doing when she figures out the Lament Configuration. She rejects the Cenobites’ offer. The book and film differ on who is seen to be breaking the contract. But the Cenobites are neither angel nor demon, regardless of the attributes they share in the first book or film. They do not correspond to the hierarchy of the Testaments, nor Gnostic scrolls. Pinhead is not the leader of The Order of the Gash, only a small nail in its architecture.

The Christianization of Hellraiser

By the sequel, Julia serves the source of this dimension’s power: Leviathan, “the god of flesh, hunger, and desire.” She is no angel. Members of the Order of the Gash tear new souls apart.

In Hellbound: Hellraiser II, we learn Cenobites are former mortals. Hell Priest was originally a regular person who opened the Lament Configuration, went through the trials of the Cenobites, and died soon after World War I. Barker consulted on Epic Comics’ 1989 to 1992 run, continuing the Hellraiser arc, which fed the mythology, and altered the philosophy.

By Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth (1992) Pinhead has been split into two halves, and his evil half is bent on world domination and torturing humanity for the sadistic thrill. Hellraiser: Bloodline (1996) marked the first overt connection to Western concepts of evil. The demon Angelique (Valentina Vargas) is a succubus princess of hell, and the daughter of Leviathan. Subsequent movies slowly (and boringly) transitioned the Leviathan’s Labyrinth into the lake of fire Hell from the Book of Revolutions.

But then in the book The Scarlet Gospels (2015), Barker also leans into the Judeo-Christian mythology, favoring the New Testament as a crutch in this belated literary sequel to The Hellbound Heart. It is also where Barker officially names the Pinhead character “The Hell Priest.” Barker infers that the nails which adorn the Priest were golden when the hammer fell, but grew dark.

At this stage of the game, the pointy one is murdering practitioners of true magic in a quest to absorb every source on Earth. The Hell Priest degrades and massacres all magicians but one, Felixson, and he turns him into a slave.

Hired by a representative of one of the executed magicians, Barker’s occult detective series hero, Harry D’Amour, goes to Hell through a portal conveniently located in Manhattan. He and his ad hoc gang of heroes, learn that Lucifer is MIA and a new demon civilization grabbed power while he was out. It turns out the devil’s throne room is his tomb. Lucifer committed suicide after God’s exile, and the Hellraiser entry lives up to its name. The Priest (Pinhead) claims dominion, blood is spilled, Lucifer rises. But the Cenobites battle the hellions, so they cannot be demons. It all goes to Hell anyway, and Satan escapes to New York. If he can make it anywhere, he can make it there.

The Cenobites’ slide into the realm of demons and angels, and appear to be spreading at an alarming rate. Hellraiser maintains its own mythology, and Barker’s creatures still fill a darker need than mere wanton desires of servants of a vengeful god.

It was a departure from the original concept of the Cenobites, and one that the 2022 movie tellingly ignores. For here is the first Hellraiser movie in decades to go back to the source, where the Cenobites offer you heaven and hell, depending on your point of view. It’s all the same poison.

Hellraiser is streaming on Hulu.