Francis Ford Coppola Movies Ranked from Worst to Best

The Godfather changed motion pictures, and Francis Ford Coppola continues innovating. But is Don Corleone really the star of Coppola’s best film?

Francis Ford Coppola may very well be the greatest American filmmaker. The Godfather, an epic three-motion-picture coup, redefined gangster movies and film; Apocalypse Now remains the greatest Vietnam War allegory ever made; Bram Stoker’s Dracula is perched atop most lists of horror classics. Coppola hit every genre, created art for art’s sake, and still managed to touch the pulse of moviegoers’ needs, desires, and fantasies.

More than anything, Coppola pursues innovation. This was exemplified in Distant Vision, which presented live cinema, performed twice, broadcast live to select screening rooms in 2015 and 2016, and not included in the list. The 25-minute film was made with students, staff, and teachers at UCLA, Coppola’s alma mater.

Coppola learned his trade at the “Roger Corman Film Academy,” where fresh filmmakers graduated by finishing movies quickly with pocket change for funding. By the time Coppola sandwiched the 1974 paranoid masterpiece The Conversation between The Godfather and The Godfather, Part II, he was already in the middle of a string of films which weren’t just critical and commercial successes, but masterpieces that enriched cinema as an artform. Then he sits back and makes some wine. Ti saluto, don Coppola, cent’anni. Here are your films ranked in order of their growth and your expertise.

25. Battle Beyond the Sun (1959)

Coppola was still a film student when Roger Corman hired him to Americanize the 1959 Soviet science fiction movie Nebo Zovyot into the English-dubbed and re-edited Battle Beyond the Sun. Filmed during the nascent “space race” period, two nations want to be the first to land a spacecraft on Mars. Coppola changed the USSR and the USA to the fictional future nations North Hemis and South Hemis.

The journey goes awry when a rocket malfunctions, and a craft drifts toward the sun. The rival country’s crew rescues the astronauts from the other vessel and continue the Mars mission together. They don’t expect to find life on Mars, and are monstrously surprised. Coppola almost makes it all make sense, but doesn’t put a personal spin on what was a bit of an intergalactic salvage job.

24. Tonight for Sure (1962)

In many interviews, Coppola admitted he’s been uncomfortable in the past about asking people to undress. This makes Tonight for Sure a seeming oddity. The film began as a sexploitation short, called “The Peeper,” Coppola made when he was a student at UCLA. It is the story of a peeping tom trying to spy on a photo session through a telescope, but all he gets are images of random body parts like a bellybutton or an elbow.

Coppola fused the film into an unfinished Western set in a nudist colony made by Jerry Schafer. In it, the League Against Nudity tries to rebrand the wild west as “the decent west.” In a precursor to the mechanics behind The Conversation, the pious protestors’ scheme begins by sabotaging the fuse box at the Harem Club, “home of the most beautiful girls in burlesque!” It gets crazier after midnight, but not much better.

23. The Bellboy and the Playgirls (1962)

“Never bet on an inside straight unless the game is fixed,” we learn in The Bellboy and the Playgirls. “Then it’s a crooked straight.” The film is a re-edited version of West German director Fritz Umgelter’s film Mit Eva fing die Sünde an (Sin Began with Eve) (1958).

Coppola was paid $250 to add a nude section in color 3D, which he shot with his classmate, future cult filmmaker Jack Hill (Foxy Brown), who was paid $25. Their segments concern George, a bellboy who wants to be the hotel detective. He infiltrates a room of lingerie models to uncover immoral doings, but only exposes himself as a physical comedian.

22. Jack (1996)

As exciting as it is to envision Robin Williams’ energy contained in a 10-year-old’s psyche, Jack is less lighting-in-a-bottle than farts in a can. While Tom Hanks’ growth spurt in Big was caused by magic. Jack Powell matures because of a rare and vague medical affliction which makes him age at four times the normal rate.

Coppola’s Jack is an inadvertent study of denial. Its most transparent subject is Diane Lane as Jack’s mother. During a scene where she looks through pictures of her son, aged as he is on his first day of school, her face shows no evidence to say this boy will die young, but Lane imposes underlying sadness through the still-occurring memories. Jack isn’t for kids, although most of the jokes are. Yet it’s also not really for adults, or it would have ordered a more serious examination. The movie was made for Coppola. He wanted to see a comically skewered saccharine tearjerker, and wanted to see Robin Williams play it.

21. Twixt (2011)

“How does it feel being a bargain-basement Stephen King,” Bruce Dern’s Sheriff Bobby LaGrange asks Val Kilmer’s Hall Baltimore. The ghost story writer proves his critics right by sinking lower into the comfortable populism of “bulletproof” darkness. Once Elle Fanning’s V flits in as a spectral presence, and children rise from shallow graves to dance like Carnival of Souls (1962) outtakes, we sense this is a scary movie. But the frights are obscured by grief and distracted by the persistent memory of daylight savings time.

A big clock in the center of town has seven faces so that everyone always knows the time, but none are set the same. Kilmer clearly enjoys the hours spent in King’s shadow, drinking with Edgar Allan Poe at a miniature Overlook Hotel bar. His “fog on the lake” take is unforgettable. Dern is at his most Dern, letting fly with one of his most batty characters in a subtle vampire flick with very little bite. It was preordained. The finished novel in the film, “The Vampire Executioner,” only sells 30,000 copies too. That seems like too many.

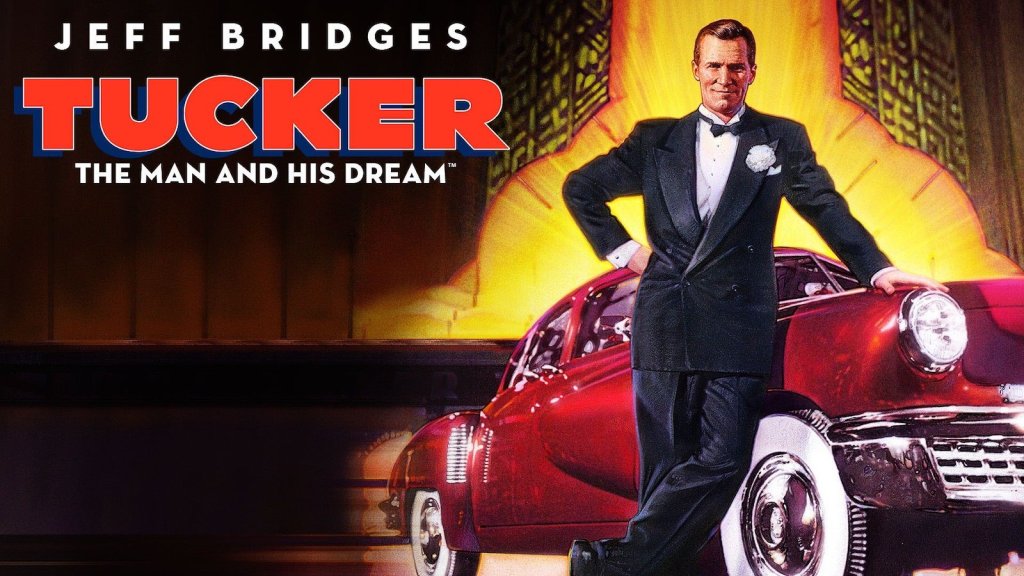

20. Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988)

Tucker: The Man and His Dream is an over-optimistic telling of the life of Preston Tucker. The automotive innovator is played by Jeff Bridges, singing “Hold That Tiger” with a broad smile that gives hope to the hopeless, overwork to some jobless, and a wife (Joan Allen) and family so cheerful you can’t help but root for them. The audience really gets in his tank when Tucker labels the big three automakers “mass murderers” for their reckless disregard of the people who drive their cars. That doesn’t win him any points in Detroit.

During World War II, Tucker invented the Tucker Turret for Air Corps bombers. Initially, it was for an over-accelerating land vehicle, and he wants to put that knowledge to use for a truly modern American automobile which would include safety features like pop-out windshields and seat belts. It would also get great gas mileage. That’s the post-war dream, and Tucker is just the underdog to get put to sleep for it.

19. Gardens of Stone (1987)

Based on the novel by Nicholas Proffitt, Gardens of Stone is set in 1968. Sgt. Clell Hazard (James Caan), who served in the Korean War and Vietnam, is stationed with the Old Guard, an elite unit at Arlington National Cemetery that’s overseeing the burial of too many young soldiers. He believes the war can be won, and wants to train recruits to survive. His boss, Sgt. Maj. “Goody” Nelson (James Earl Jones), is less sure. His new love, Samantha Davis (Anjelica Huston), is a Washington Post writer who is unabashedly anti-war.

The depth of Caan’s performance is unexpected, and the romance between his character and Huston’s is a moving and deeply nuanced adult love story. Jones’ cynicism is sublimely funny. Cutting across the discourse is the Old Guard’s newest rookie. Jackie Willow (D.B. Sweeney) is an enlisted man hungry for action and anxious to be sent to Vietnam. There’s no mystery to how this war will turn out. Coppola honors the brave unquestioning soldiers, corralled to the front lines for their political cluelessness.

18. Tetro (2007)

Tetro has “great stories, but no ending,” to paraphrase the inner film’s own self-assessment. “It doesn’t have to have an ending.” Coppola, who rehearses movies like they are stage plays, collaborates with Vincent Gallo, renowned for his improvisational process as both an actor and director. Gallo is perfect as the eccentric, and volatile genius, Tetro.

The film feels very personal, especially the family rivalry, which dissembles the Coppola dynasty dynamic. This guilt of overachievement does not stop Coppola from consistently innovating with the form of motion pictures, nor from presenting something cinematically original. Filmed in black and white with flashbacks in color, Coppola further shades the movie with surrealistic twists on other filmmakers’ styles, and genre collisions. Tetro is also very operatic, Oedipal, and occasionally emotionally vicious.

17. The Rainmaker (1997)

John Grisham’s The Rainmaker is a David-and-Goliath story, and Coppola’s adaptation is a slingshot bullseye. Southern attorney Rudy Baylor (Matt Damon) graduated from a second-rate law school and is living in his car. Deck Shifflet (Danny DeVito) never passed the bar exam but legal statutes come second nature. This is almost buddy movie material. But when Mary Kay Place’s son (Johnny Whitworth) is refused cancer treatment by his insurer, the scrappy legal team is up against more than just the corporate attorney, played by Jon Voight with a classy kind of sleaze. They are fighting the entire industry.

Coppola hits every beat in plot and characterization. The focus on supporting characters, and the expert attention to hourly billing rates make for a believable watch. The Rainmaker comes close to being a feel-good movie but takes reality into account for far more cynical concluding remarks.

16. Youth Without Youth (2007)

“Whoever dies on Easter goes straight to heaven,” we are promised in Youth Without Youth. Coppola broke Coppola’s 10-year fast from moviemaking to adapt a novella by the Romanian-born Mircea Eliade. Tim Roth performs multiple roles as Dominic Matei, a 70-year-old Romanian professor of linguistics whose existential crisis collides with a catastrophic event, resulting in spontaneous rejuvenation. A scene where his rotten teeth spill out over a hospital floor, pushed out by a healthy set, is a realistically rendered minor miracle.

The impossible recovery is reported on the same pages as the slowly rising seeds of World War II, and Nazi scientists want to weaponize it. Forced into exile, Dominic can finally finish his life’s work but only at the cost of the love of his life. The film is a beautifully shot, expertly acted ball of confusion. It works emotionally, allowing the story to find its own way and is unsettlingly satisfying.

15. You’re a Big Boy Now (1966)

Coppola directed the feature adaptation of David Benedictus’ coming-of-age novel You’re a Big Boy Now to complete his master’s thesis and graduate UCLA. Most of the $800,000 budget was spent on 35mm film. Premiering in competition at Cannes, Coppola’s student film was picked up for distribution by Warner Bros., which was almost unprecedented; it also garnered a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination for Geraldine Page.

Coming out a year before Mike Nichols’ iconic generational study The Graduate (1967), the young man in Coppola’s film is the sheltered Bernard Chanticleer (Peter Kastner). He works in the New York Public Library where his father (Rip Torn) holds an important position while holding his son in a disdainful mistrust. Amy Partlett, played by Karen Black in her first screen appearance, provides as much sweet contrast as the soundtrack by the Lovin’ Spoonful. Leaning into the counterculture, all adults are captured in boring neutral tones against the teenagers’ vibrant colorful world. Coppola would return to this color coding several times over in his career.

14. Finian’s Rainbow (1968)

Finian’s Rainbow hit theaters toward the end of the movie musical’s last gasp in old Hollywood. Think My Fair Lady (1964) and The Sound of Music (1965). Coppola’s tonal throwback is steeped in the whimsy of classics like Swing Time or Top Hat, moves quickly, and has fun with itself. The script was adapted by the original 1947 play’s creative team Fred Saidy and E.Y. Harburg (who wrote all the songs for The Wizard of Oz, including “Over the Rainbow”). Finian’s Rainbow’s score was updated for a supposedly ‘60s audience, but the real pot of gold is the mix of generations making beautiful music together.

Finian McLonergan may be Fred Astaire’s best characterization after On the Beach. He is not playing a version of himself and he’s not afraid to show his age. British pop singer Petula Clark brings her own personality to Sharon McLonergan, brightening even the dark moments. Dancer Barbara Hancock’s moves more than compensate for any dialogue lost in her role as Susan the Silent. Tommy Steele almost makes you believe in leprechauns. In spite of budget limitations and the too-innocent take on its civil rights satire, Finian’s Rainbow could be considered one of the best-directed musicals of the 1960s.

13. One from the Heart (1982)

Coppola’s Zoetrope Studios was intended as a gift to himself in the form of a space for auteur filmmakers to reimagine cinema. He created a revolutionary realm for moviemaking and expanded its canvas. One from the Heart was, as the title might suggest, the director’s most personal project. Coppola didn’t concern himself with how it would be received, just how it would be framed. Then he blanketed it with a gorgeous score by Tom Waits, who performed it with Crystal Gayle, and it went out as a work of art.

The production design is as spectacular as any extravaganza from the golden age of Hollywood. Coppola recreated the Las Vegas strip on his soundstages. Then he populated it with magic: a circus performer named Leila, portrayed by the already mystical Nastassja Kinski, and a dancer named Ray, played by Raul Julia at his most charismatic. In truth, Ray works as a waiter at a 24-hour buffet, but Frannie (Teri Garr) and Hank (Frederic Forrest), the troubled couple who anchor the film, have had enough reality. Coppola provides the fantasy.

12. Dementia 13 (1963)

“Castle Haloran is a bit perplexing, a very strange place really, old and musty, the kind of place you’d expect a ghost to like to wander around in,” Louise Haloran (Luana Anders) describes the oppressive family estate. Part ghost story, part ax murder spree, and part psychological breakdown allegory, Dementia 13 is a love letter to Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, masquerading as a rip-off.

Dementia 13 stars William Campbell as moody sculptor Richard Haloran, heir to the family fortune, and engaged to Kane (Mary Mitchel), a Lady Macbeth wannabe. Working for Roger Corman’s productions, Dementia 13 was made with money left over from The Young Racers, another Corman low-budget film which Coppola worked on as sound man. Shot in black and white, cinematographer Charles Hannawalt still manages to anticipate Italian Giallo horror films. We can see how quickly Coppola is learning how to be a filmmaker. His cameras squeeze subjects into ever-tightening frames. The terror is elusive, but ultimately suffocating.

11. The Rain People (1969)

The Rain People is a precursor to Martin Scorsese’s 1974 road picture Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. It is one of the era’s cinematic journeys through America’s heartland like Easy Rider (1969), except in a family station wagon instead of a chopped motorcycle. Shirley Knight plays Natalie Ravenna, who is trapped in a stale marriage, and pregnant with a child she’s not sure she wants (Knight was pregnant during the shoot). She dutifully calls her husband from roadside phone booths, but acknowledges herself as “irresponsible, cruel, and aimless.”

Natalie picks up hitchhiker Jimmie “Killer” Kilgannon (James Caan), a former college football player who suffered brain damage on the field and is rendered an innocent. He does what he’s told because “it’s easy,” adding shades of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men. When Natalie picks Jimmie up, he’s got an envelope with some cash and a job offer in West Virginia. Robert Duvall plays a dryly insidious highway patrolman. People made of rain disappear when they cry, and Coppola opens an umbrella for those who are too sensitive for this world.

10. The Cotton Club (1984)

The Cotton Club is a love letter to the gangster movie genre and the jazz age, and is set where the two worlds met: the Cotton Club in Harlem. Owned by Owen “the Killer” Madden (Bob Hoskins), the gangsters’ gangster, it is the most inviting crime scene in the city. The film opens in 1928, Dixie Dwyer (Richard Gere) is a cornet player about to turn a solo into a sultry duet when he knocks Dutch Schultz (James Remar) out of the way of a pipe bomb. He’s got a Dutch uncle from then ‘til doomsday, which is always in the shadows with such a possessive and paranoid mob boss keeping score.

Gregory Hines acts and dances the part of Sandman Williams (Gregory Hines), partnered with his brother Clay (Maurice Hines) until Lila Rose Oliver (Lonette McKee), a light-skinned chorus girl trying to hide her Black heritage and make it as a singer, expands his horizons. Nicolas Cage’s Vincent “Mad Dog” Coll brings high-strung dissonance while Laurence Fishburne’s Bumpy Rhodes provides low-key counterpoint. The film is a bit muddled, admittedly, but so much fun I watch it annually. Sometimes just to hear McKee sing “Ill Wind.”

9. The Godfather, Part III (1990)

The Godfather, Part III is pilloried as a cinematic disappointment and a wart on the career of Sofia Coppola, Francis’ dutiful daughter who filled in at the last minute. She gave a realistic performance, but was gutted. These are unfair assessments. The film was nominated for seven Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director. Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas, released that same year, got six nominations.

The Godfather, Part III is the first of the Corleone family movies with no assistance from the source material, Mario Puzo’s novel The Godfather. Al Pacino’s Michael Corleone is isolated, there is no Marlon Brando or Robert De Niro to bring Vito’s reasoning. He doesn’t have the counsel of Robert Duvall’s consigliere Tom Hagen, or even caporegime Clemenza. Reviewers jumped ship, claiming Coppola mimicked the first two films, only much too slowly, and without enough action. Again, this is wrong. There is a helicopter mass execution, an ear bitten off by Andy Garcia’s bare teeth, and an international criminal conspiracy which dwarfs the Corleone family’s vast holdings: the Holy Roman Church. The final chapter in the Corleone saga only pales in comparison to the first two films. It’s still mob royalty.

8. The Outsiders (1983)

Adapted from S.E. Hinton’s 1967 novel, The Outsiders is set in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which has a nice side of town and a wrong side of the tracks. Each is defended by gangs: The Socs, upper-class white trash Wasps with fancy cars, and the Greasers, the longhaired white trash who fix and fill those cars. In the crossroads sit Ponyboy Curtis (C. Thomas Howell) and Cherry Valance (Diane Lane). Not lovers, but closer than friends, they represent all that is golden in the rival camps. Johnny Cade (Ralph Macchio) and Dallas “Dally” Winston (Matt Dillon) are perennially gilded.

The rest of the Curtis family is Sodapop (Rob Lowe) and Darrel (Patrick Swayze), who is over 18 and responsible for his brothers. Everything turns bad after a fatal knife fight sends the youngest Greasers on the run where the outlaw fugitives prove themselves local heroes. Only Coppola could turn the Brat Pack into the Dead End Kids. Emelio Esteves plays Two-Bit Matthews, and a very toothy Tom Cruise tumbles through the small part of Steve Randle. The film is timeless, infinitely rewatchable, and both anguished and fun. You can actually feel Coppola’s enjoyment in making it.

7. Peggy Sue Got Married (1986)

In Peggy Sue Got Married, Kathleen Turner’s Peggy Sue admits to “certain unresolved feelings” about her husband Will (Nicolas Cage). “I don’t trust him.” Through the magic of box office timing, a wave of contemporary time warp films enables Peggy Sue to go back to a much more innocent era: her senior year in high school. Apparently, there’s a wormhole there from her 25th class reunion which hasn’t been breached in over 600 years.

Stuck in the same dilemma as Back to the Future (1985), Peggy Sue may never be able to get back to her present, and if she does, she wants a new reality. This literal trip back to memory lane gives Peggy Sue choices. One of her most inspired is to pre-steal the Beatles’ “She Loves You,” as a parting gift to her doo-wop/rhythm and blues-singing boyfriend and future husband. He changes the lyrical hook, which would make the song a hit. It’s a giddy scene which encapsulates a fun movie, having a blast with itself without losing sight of the fragile melancholy at the center.

6. Rumble Fish (1983)

Rumble Fish is also adapted from an S.E. Hinton novel, but with Coppola’s sensibility overriding the starker story. Rusty James is the epitome of conflicted youth, but Matt Dillon is not doing the angsty James Dean take he did in The Outsiders. Rusty is doomed, but fully prepared and eager to pursue it, just like his older brother, Motorcycle Boy. Mickey Rourke gives one of his most enigmatic portrayals in a long string of unique characterizations. Something fried inside Motorcycle Boy’s mind, but the only monkey he’s got on his back is a vindictive cop.

Also starring Diane Lane, Dennis Hopper, and Vincent Spano, Rumble Fish is a gang movie told through texture, warped time, and emotional perception rather than straight narrative. The movie is in black and white, matching Motorcycle Boy’s color-blindness, but the teenage spirit has color, similar to what Coppola did in You’re a Big Boy Now. The piranhas at the pet store are red and blue. Coppola called Rumble Fish an “art film for teenagers” and employs his most inventive camera placement. It is a major gamble in original filmmaking, and Coppola takes the win.

5. Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992)

Coppola’s adaptive literary legacy lives on in the undead. He’d already legitimized mob movies based on a pulpy bestseller, so he moved on to make a classic and influential novel into a horror genre masterpiece. For all the monstrous personalities hidden behind the centuries-old warrior, Bram Stoker’s Dracula shows Count Dracula at his most human. If ever a cinematic Dracula deserves to live through an adaptation of the story, it is Gary Oldman’s. Winona Ryder makes an irresistible case for Mina Harker’s truly fated death. She outlives her immortal count, and raises the film to romantic tragedy in epic goth fashion.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula is about love and a carnal desire spanning centuries, from the harsh battlefields of medieval Transylvania to London’s Carfax Abbey, procured at a reasonable price by Jonathan Harker (Keanu Reeves). It is also about an insidiously seductive terror. Coppola captures the lethally erotic atmosphere of the vampire’s brides, and the expansive claustrophobic horror of the castle in the Carpathian Mountains. Sadie Frost’s Lucy Westenra is sexual liberation made flesh. Dwight Frye who originated the role of Renfield in the 1931 Tod Browning classic Dracula, would happily share a rat with Tom Waits evolutionary unhinged connoisseur of lower life forms. It is horror. It is romance. But it endures on blood.

4. The Conversation (1974)

“I’m not afraid of death,” Gene Hackman’s stoically professional wiretapper Harry Caul says in The Conversation. “I am afraid of murder.” Packed into a van with his assistant Stan (John Cazale), Caul directs a surveillance team to record a secret rendezvous held in a public place: The young couple Ann (Cindy Williams) and Mark (Frederic Forrest) circling San Francisco’s Union Square during a packed lunch break. Partly inspired by Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966), if run under the shower in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, the suspense hinges on the interpretation of the line “he’d kill us if he had the chance.” Coming two years after the Watergate break-in, the first suspect appears to be the director (Robert Duvall) of the large corporation who hired Caul. But a more duplicitous menace comes in the pincer-squeezing subterfuge offered by his assistant Martin Stett (Harrison Ford).

Harry only cares about technical results, suppressing his part in human consequences until guilt pushes him into a paranoia which renders him impotent. When Harry thinks he hears a murder behind a wall, he hides under the covers in the next room. Timeless and of the moment, The Conversation has one of the most surprising twists in film.

3. The Godfather, Part II (1974)

The Godfather, Part II was the first movie sequel to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. Many film enthusiasts prefer it over The Godfather. For me, the reason it comes in lower is also the film’s greatest strength: Coppola’s artistic ambition. The sequel tells two semi-parallel stories, moving forward through two different timelines. Both succeed expertly, but it splits the focus. The Godfather tells one unified story, and what a story! It also carries more emotional impact because we are introduced to the Corleone family.

Opening about a decade after the conclusion of The Godfather, Part II finds Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) as the established family head, expanding the Corleone empire into Las Vegas, Florida, and Cuba. Details of his progress are interspersed with flashbacks to the early life of Vito Andolini (Robert De Niro) whose family is killed by a Mafia don in Sicily. He comes to America at the age of nine, settling in New York City. He takes the name of his town, Corleone, at Ellis Island and grows an empire. Michael, by contrast, loses his soul, sacrificing morality, his father’s values, and custody of his children. Still, he wins a senate hearing. Coppola maintains mood, atmosphere, period, and the subtext of William Shakespear’s King Lear.

2. Apocalypse Now (1979)

Physically damaging to make, Apocalypse Now is a perfect film experience. It is inspired by Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad’s novel about a former colonel named Kurtz who penetrates the free Congo and proclaims himself God. To bring this awesome presence to the war in Vietnam, the film needed “a poet-warrior in the classic sense,” as Dennis Hopper’s photojournalist describes. Coppola unleashed the full weight of Marlon Brando, an acting deity, to play Col. Kurtz. His mirror image, the assassin Capt. Willard, is played by Martin Sheen in one of the most tightly unhinged characterizations in film.

He’s got fierce competition in Laurence Fishburne’s jumpy teenaged machine-gunner, as well as the mango-loving/tiger-hating Chef (Fredric Forrest). But Col. Kilgore (Robert Duvall) liberates the most quotable moments: “I love the smell of napalm in the morning,” he says after a successful cluster-bombing; “Charlie don’t surf,” after clearing a beach of pesky enemies. His most eloquent roar comes as his choppers blare Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” on their descent on Vietnamese schoolchildren. Coppola is a master of emotional and intellectual storytelling. He sums up jungle warfare in one exchange: “Who’s the commanding officer here?” Willard asks a sniper, who counters, “Aren’t you?”

1. The Godfather (1972)

The Godfather is widely considered the greatest film of all time. Made under its $6 million budget and completed ahead of schedule, it was the first film to take in a million bucks a day. It was nominated for 11 Oscars and won three. Perfectly edited, immaculately acted with realistic warts intact, and expertly framed, it set high standards for a new Hollywood. It is the ultimate gangster movie, and the most loyal family film in cinema. But it is so much more. Based on Mario Puzo’s novel, The Godfather is a movie you can watch dozens of times and still find something as fresh as a sprig of basil in a sauce prepared by caporegime Peter Clemenza (Richard Castellano).

Paramount Pictures, whose logo is a mountain top, has come to claim The Godfather as its pinnacle achievement, but Coppola had to fight to cast Marlon Brando as Don Vito Corleone and Al Pacino as his youngest son, Michael. The cast became acting royalty, reshaping leading players in a new era of realistic cinema: Audiences recognized the aggressive hothead son Sonny played by Caan, empathized with Cazale’s sad Fredo, and still suspected Diane Keaton’s Kay Adams, who becomes Mrs. Michael Corleone, the new don’s most intimate outsider. The film changed everything.