Everything Everywhere All At Once and the Film Festivals That Pave the Way to Oscar Gold

Exclusive: We chat with Everything Everywhere producer Jonathan Wang and awards experts about the role film festivals like SXSW play during Oscar season.

To four people huddled around their laptops and devices during the wee small hours of a Tuesday morning, it may as well have been the Super Bowl. Hearing your name and those of your colleagues uttered as the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announces this year’s Oscar nominees has that effect. And to Jonathan Wang, producer of Everything Everywhere All at Once, it was nothing short of surreal as he realized their little movie with wobbly hot dog fingers was on track to score 11 Oscar nominations—making it this year’s de facto frontrunner.

“There’s a video of me in the Zoom being like, ‘We’re on pace for 11,’ and everyone’s like, ‘What are you talking about?!’” Wang recalls. “And then by the end of it, we did get 11, and we were standing and cheering.” It was a heck of a way to begin a workday for Wang, directors Dan Kwan and Daniel Scheinert (aka “Daniels”), and stars Michelle Yeoh and Ke Huy Quan—now Oscar nominees all. Yet it also was the beginning of the end of a journey that started a long time ago. In Texas.

When the Oscars telecast beams out of the Dolby Theatre on Sunday, March 12, it will be one year and a day since Everything Everywhere All at Once enjoyed its world premiere at the SXSW Film Festival. A dazzlingly original film that marries the existential weight of the universe to the intimacy of the Asian American immigrant experience—and all by way of multiverse theory, martial arts, and those marvelous hot dog fingers—the movie appeared to be a perfect opening night film for a festival at the intersection of cinema, music, technology, and just plain old innovation. It made sense for SXSW, but the Academy?

For his part, Wang freely admits the word “Oscar” never crossed his mind when reading the script for the film. He and Daniels go back 12 years, including when Wang and Kwan together brought the music video “My Machines” to Austin, where it won the Jury Award Prize in 2012, and Wang states assuredly that “our tastes have become a bit of a meld” ever since. They look for what makes them laugh, as well as the deeper meaning behind those chuckles. However, what they believe is the deeper meaning in images that revel in our “fun, weird, flatulent contradictions” is not necessarily what the Academy thinks.

Nonetheless, Claudette Godfrey, the director of film festival programming at SXSW, immediately saw the long-distance appeal of the film, knowing since opening night in 2022 that this movie could go far. Indeed, indie studio A24 screened Everything for the festival’s programmers months before releasing the first trailer in December 2021, and the SXSW team instantly became its champions, referring to it among themselves as “the best movie ever.” Godfrey still remembers that euphoric opening night, too.

“Even the most revered, famous filmmakers wonder, ‘Are they going to like it? Are they going to like me?’” Godfrey says with visible affection in 2023. “And I just looked [Daniels] in the eye and said, ‘Your whole life is going to change after this moment.’” Come Oscar morning, she found herself texting the directors two sentences: “Fuck yes! A thousand percent deserved.”

SXSW and the Larger Film Festival Circuit

Godfrey saw its potential as an awards contender that night, and over the next 12 months, even the most skeptical of Oscar prognosticators came around to agreeing. Everything Everywhere’s nominations are a major coup for SXSW, marking the first time a film that had its world premiere at the fest got into the Best Picture race (although previous documentaries and short films that premiered at SXSW have won Oscars). Other SXSW 2022 alumni like Andrea Riseborough in To Leslie and the animated film Marcel the Shell with Shoes On also were nominated in their respective categories.

But while this is a feather in SXSW’s cap, the prospect of festival darlings becoming Oscar frontrunners is less a fluke than a fact of nature in today’s cinematic ecosystem. Ever since Crash (2005) became the first Best Picture winner to be acquired at a festival (the Toronto International Film Festival), fests have increasingly paved the path to Oscar gold. They of course played a role before 2005 as well, with DreamWorks and Sam Mendes’ American Beauty (1999) winning the top Oscar prize after premiering at TIFF. That was a studio effort, though, and released during a time when movies like Gladiator and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King could still win Best Picture.

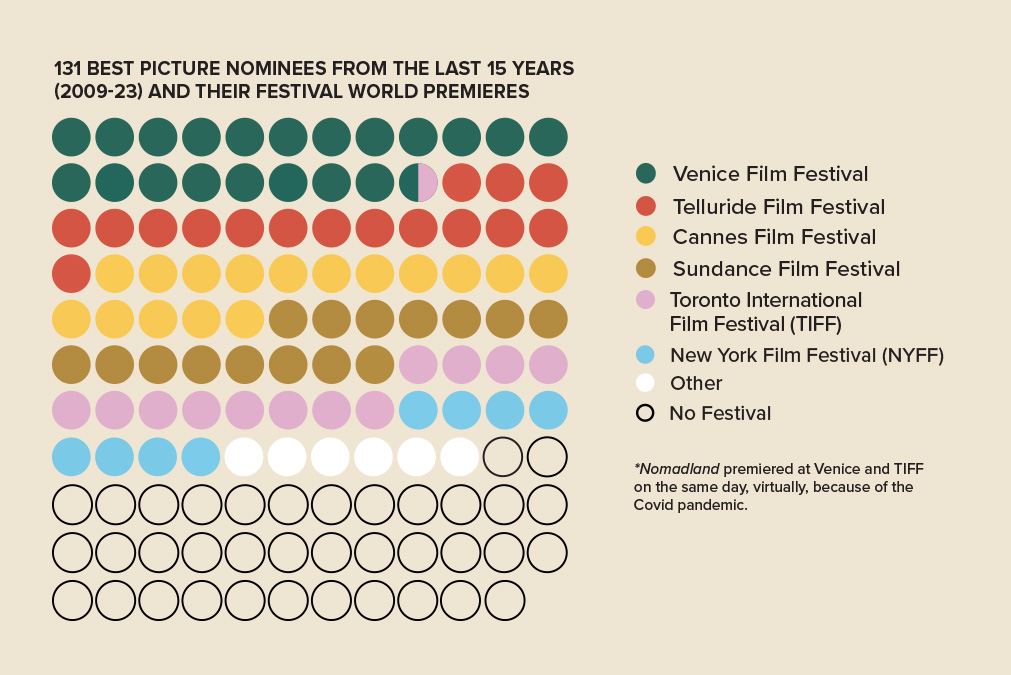

Twenty years ago, there were merely five Best Picture nominees, and only one of them premiered at a film festival (Roman Polanski’s The Pianist, out of Cannes). In 2023, nine of the 10 Best Picture nominees played at least one festival, including Top Gun: Maverick (also Cannes). Of the 131 films nominated for Best Picture in the last 15 years, nearly three-quarters premiered at a festival, including every Best Picture winner.

One source we spoke to, who’s close to several of this year’s Oscar nominees, explains, “[Festivals] create a kind of sustained word of mouth that eventizes the way of looking at it.” This includes not just world premieres, which are valuable to a festival’s bragging rights, but also regional fests across the calendar. Whether they play in Woodstock or Nantucket after Venice and Cannes, these movies are highlighted for general audiences and awards voters alike by sustained word of mouth.

Clayton Davis, the senior awards editor at Variety, has been studying the awards and festival circuit his entire career and speaks candidly about the value they bring to general audiences, and by extension, awards voters.

“If arthouse theaters are minimal now, then film festivals may be one of the last main stops for an adult drama or an indie project to get some eyeballs on it,” Davis says. “I’m looking at it in the regional game, [like] the Middleburg Film Festival.” October’s Middleburg is also a good example of premiering awards-friendly films that were already in limited release in the U.S. after debuting at other festivals (Tár, The Banshees of Inisherin, Decision to Leave) and those that still premiered elsewhere but were not yet out in general theaters, such as The Whale.

In fact, months later and going into awards season, Academy and guild voters at special screenings of The Whale were still saying they showed up because Brendan Fraser got a standing ovation in Venice. They don’t care about who’s first, necessarily; they just like hearing good things.

With that said, most awards watchers and forecasters will contend Oscar season begins in early September when a spate of specific film festivals kick off near simultaneously.

“I would say there’s the big four of the fall: Venice, Telluride, Toronto, and the New York Film Festival,” Davis explains. “I see the distinction [between them], but the average person probably does not.” Nearly 44 percent of the last 15 years of Best Picture nominees, and over 85 percent of the winners, premiered at those fests. Their popularity with studios and awards publicists extends partially from where they appear on the calendar. While the Cannes Film Festival is arguably the most prestigious fest (and older than the other three of those September events), Davis notes, “A lot of people don’t want to blow their load at Cannes because then you have to sustain the buzz for eight, nine more months.”

Among the big four of the fall, Venice is always the first since it’s also the oldest festival in the world, beginning in 1932. Perhaps for that reason, the Italian festival has the largest tally of recent Best Picture nominee world premieres, although many of the films that debut there go on to play at one or two of the other major fall fests, but rarely all four. Studios are selective, and some fests demand exclusivity.

Says Davis, “I think for a filmmaker, you’ve got to just want to get into one, but there is prestige about certain ones that you want to debut and get your first eyes on you.” For instance, Venice, like Cannes, is an international and competitive festival with a higher propensity of European critics and journalists. It’s what makes Cannes attractive for certain films like this year’s Palme d’Or winner, Triangle of Sadness, and also speaks to why the Academy, with its increasingly international voting body of recent years, can favor movies that American critics dismissed.

“Blonde debuted at Venice,” says Davis. “Makes perfect sense. I knew that Ana de Armas was in the Oscar race the whole time because what people turn their nose up at here, across the pond, and in Europe, people were like, ‘this is cinema!’”

Meanwhile, the earliest festival of the year, like SXSW, has seen a recent boost in Academy prestige. Last year’s CODA marked the first time a Sundance premiere won Best Picture. Traditionally, the January fest produces a lot of Best Picture nominees, but its wins tend to come from performances or young filmmakers’ innovations—Casey Affleck in Manchester by the Sea; J.K. Simmons in Whiplash; Emerald Fennell’s script for Promising Young Woman. Within the larger industry, Sundance is still perceived as an acquisition marketplace, spotlighting young and indie filmmakers on the rise. A24 even acquired Daniels’ Swiss Army Man there.

“Without Sundance, we wouldn’t have a career in filmmaking,” Wang acknowledges gratefully.

The Last Breath Before Oscar Night

Perceptions can, of course, change. Davis, for one, says SXSW is perceived as the “cool kids festival” in Hollywood, and he still wonders “how cool the Academy” has gotten, even with its recent influx of younger, more diverse, and international voters (which also could explain All Quiet on the Western Front and Triangle of Sadness’ over-performing nominations). But SXSW film head Godfrey isn’t too worried. Though she’s rooting for Everything Everywhere on Oscar night, she doesn’t seem to mind if the Academy is cool enough or not yet.

“I think it’s great to not be in the pressure position of being the first big film festival of the year or the festival that’s going to have all the Oscar nominees,” Godfrey says. “Those kinds of things are nice, but I think we have our own little spot. Having Dungeons & Dragons, what other festival does that work in the way it works at SXSW? We have a unique audience coming from all these other industries where they don’t go to film festivals, but they’re going to SXSW… They’re not going to be like, ‘Let me decide if this will be on the Oscar nominations list.’”

Even so, her colleague, SXSW communications director Jody Arlington, notes Oscars’ rising tide carries all ships: “It helps lift the boats for films that aren’t part of that conversation,” Arlington says, “just because it fuels so much of the activity around this business. So it’s important that it be healthy.”

For Wang, meanwhile, it was the beginning of a journey so picture-perfect that it feels like something out of a Hollywood movie.

“I have to give kudos to A24 for believing that this would be this sort of event that would be loud,” Wang says, acknowledging it was the studio who decided to submit for SXSW, as opposed to Sundance or TIFF, in part because of the festival’s more genre-loving, idiosyncratic audience. “Also, kudos to SXSW for curating such a welcoming and film-loving community. They really set us up for success.”

When we catch up with Wang, though, the journey is still not quite over. As he speaks from his Los Angeles home, the producer’s just finished the Oscar luncheon and is headed to the BAFTAs next. It’s the culmination of a year that’s been something of a blur—and made bearable because the EEAAO team has been staying in touch via group chat. That closeness has even helped strategize a rollout and awards campaign that can occasionally be more intimate than a PR firm’s conference room. Wang, for example, accompanied Quan to Italy to do press and screenings after receiving a text that the actor didn’t want to go alone. And whether too cool for the Academy’s school of thought or not, Wang hopes Everything Everywhere helps change the dialogue around awards films.

“I hope that not only will it change SXSW’s perception as a niche market into a big fun festival… but that it’ll blow the lid off of preconceived notions of what an Oscar movie is,” Wang says. “I think that what the Oscars stand for is excellence in cinema, not just excellence in dramatic cinema or excellence in these certain kinds of facets of cinema. So if we’re able to take our movie and have it be just a wedge in the door, that opens it up a bit so that other movies can keep coming in, I think that that would be a huge point of pride in my life.”