Da 5 Bloods Opening History Montage Explained

We annotate the many historical events referenced in the first several minutes of Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods.

This article contains Da 5 Bloods spoilers.

fThe 1960s were a tumultuous time. Knowing that has become a cliché, one that’s as basic as a white bread miniseries on NBC about the decade. Nevertheless, it was a monumental moment in American history and a flashpoint for transition as Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the youth quake of baby boomers coming of age all coalesced. And it’s a decade with systemic cultural struggles that are still with us—and not something comfortingly endured and “fixed” in the relatively distant past like certain Oscar winners might suggest.

Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods astutely understands this. For here is a joint about the Vietnam War that is not set during the actual Vietnam War. Rather Da 5 Bloods explores how the fights of those days are still with us, and the bigger dream of its leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and even Stormin’ Norman remains undone. Lee is direct about this, opening his movie with a montage of events, names, and places that gives even novices a visceral snapshot of the pain of that moment—and how little has changed after the decade that supposedly changed everything.

Still, there’s a lot of history crammed into the first three minutes of Da 5 Bloods. So here’s an annotated guide that just lightly touches on the profound events shown from those heady days.

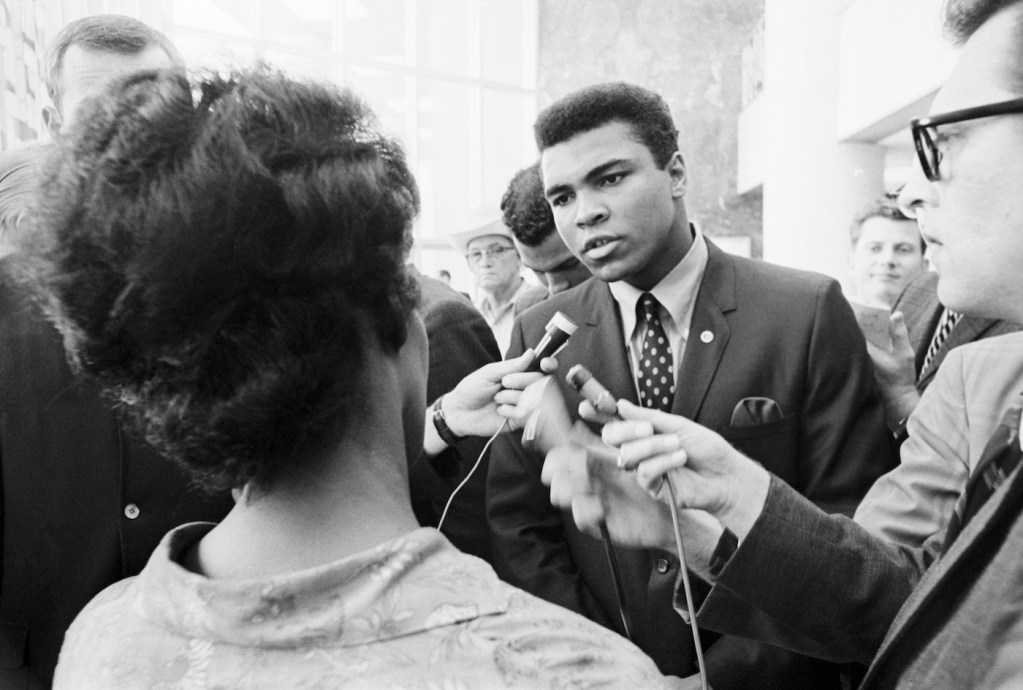

Muhammad Ali and the Draft

The first thing we hear is Muhammad Ali’s reasoning for refusing to acquiesce to the draft. “My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother or some darker people or some poor hungry people in the mud,” Ali said. “And shoot them for what? They never called me n***er, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, never robbed me of my nationality.” Ali stated this in 1978, years after the war ended. But his conscientious objection to the war carried a heavy toll.

When Ali was drafted, he was already the heavyweight champion of the world and, in his words, “The Greatest! I’m the prettiest thing that ever lived!” He shouted those words at the press in 1963 when he defeated Sonny Liston and, at the age of 22, became the youngest champion in his weight class. But three years later, he publicly announced he’d refused to be inducted in the U.S. Armed Forces after his birth date was called in 1966. By this point, the Vietnam War had seriously escalated for the U.S.—the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution was passed in August 1964 and in July of ‘65, President Lyndon B. Johnson called for 50,000 more ground troops in country, increasing the draft to 35,000 men a month.

In April 1967, Ali appeared in Houston for his scheduled induction into the U.S. Armed Forces but refused to step forward when his name was called. He was subsequently convicted of draft evasion that summer. Before he even officially refused to serve on conscientious grounds, he was being denied a boxing license in every state in the union. He was also stripped of his passport. The U.S. Supreme Court eventually overturned his conviction in 1971, but by then he’d lost three of his prime years in boxing, not entering a sanctioned bout between March 1967 and October 1970.

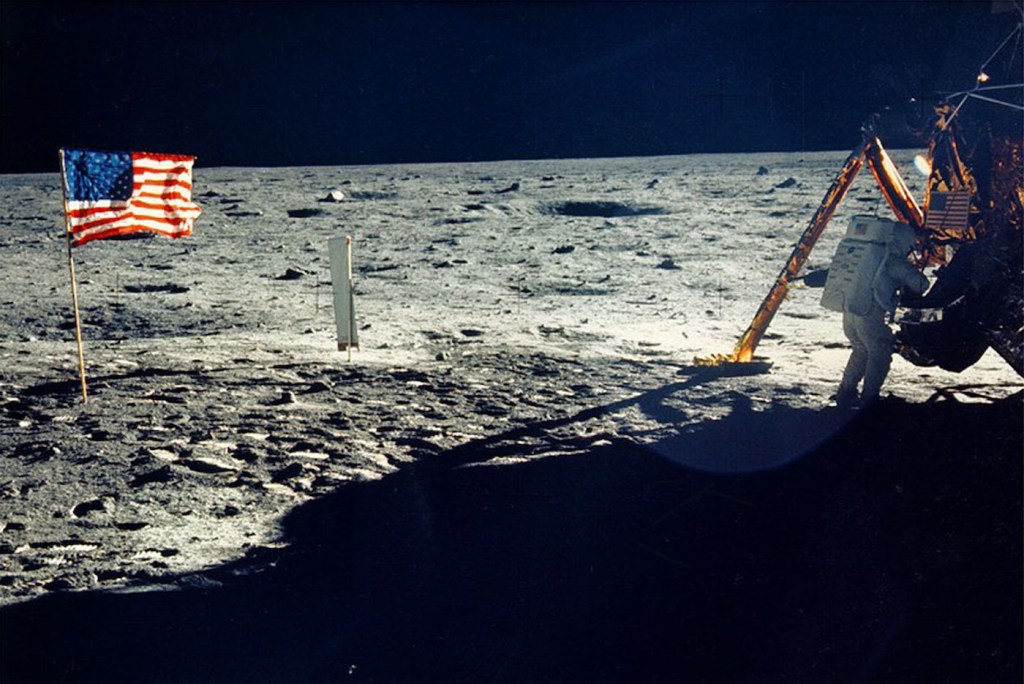

Da Moon Landing

But while Ali didn’t serve at a great personal price to himself, many other Black men who couldn’t afford the legal drain of the U.S. government coming after them did. We see some of them in Vietnam as Lee’s Da 5 Bloods montage continues, with the next major event shown being the Apollo 11 liftoff and Neil Armstrong taking one small step for man and one giant leap for mankind. Or as Lee’s movie amusingly denotes, it’s July 21, 1969 on “da moon.”

The Apollo 11 project was the transcendent culmination of years of effort, and the U.S. government finally leapfrogging past the Soviets and winning the space race. It also significantly made good on President John F. Kennedy’s challenge in May 1961 that “this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before the decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to earth.” The U.S. achieved that enormous ambition eight years later, starting essentially from scratch. But to put Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon in July 1969, the Apollo program cost the U.S. $28 billion. Considering that money was spent during the Vietnam War and strife at home—during a decade that saw the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act defang Jim Crow, while the South kicked and screamed (and killed) the whole way—many constantly challenged it as a waste of resources, particularly before the mission actually succeeded.

We see one such protest sign in Da 5 Bloods that reads, “$12 a day to feed an Astronaut. We could feed a Starving Child for $8.”

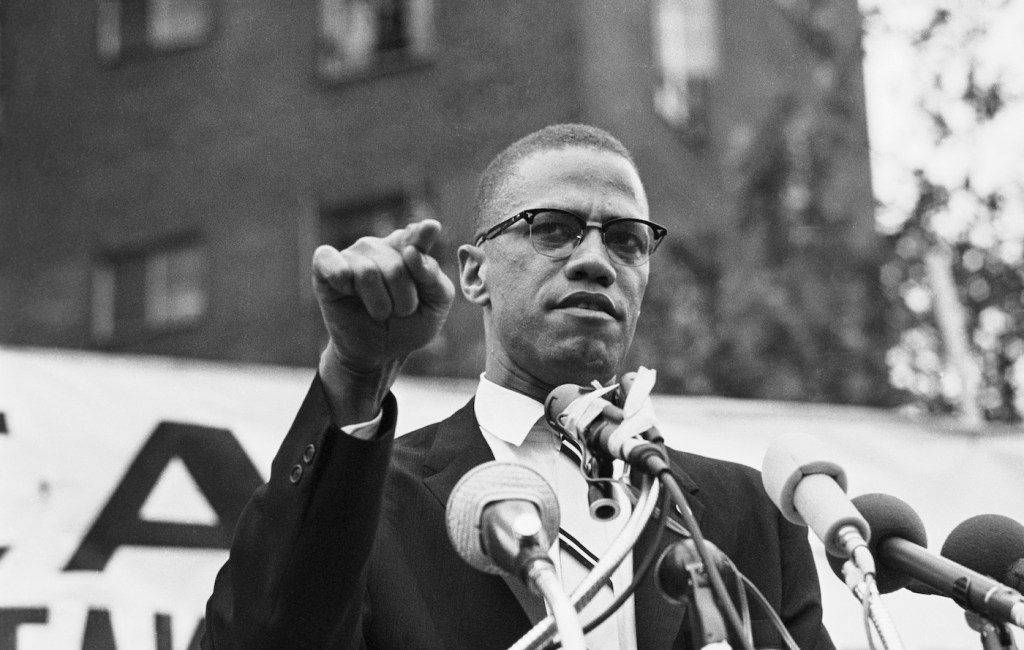

Malcolm X

The next image we see in the Da 5 Bloods montage is a speech Malcolm X gave in 1962 about the hypocrisy of the U.S. government asking black men to die in their wars. It would be presumptuous and foolhardy to pretend a few paragraphs is a full biography on Malcolm’s life, but suffice to say that by 1962 he was at the height of his power in the Nation of Islam. He had converted to the faith in 1948 after multiple family members, including brother Reginald, extolled the virtues of Islam to a sibling once nicknamed “Satan” for his opposition to organized religion. But while serving a prison sentence, the man who would become Malcolm X found the Nation of Islam’s teachings far more persuasive. It should also be noted that during this period, he had an FBI file opened on him because he wrote President Harry Truman to denounce the Korean War.

After his parole in ‘52, Malcolm travelled to the Midwest and soon became one of the Nation of Islam’s top recruiters. He first gained national notoriety in 1957 due to a now very familiar story of police brutality, in this case involving another member of the Nation of Islam, Hinton Johnson, being severely beaten by two New York City police officers. This occurred after Johnson attempted to intervene in the officers aggressively beating another Black man with nightsticks. Malcolm X got Johnson medical treatment—which he was being denied while bleeding in police custody—by organizing hundreds of Muslim followers to gather outside the police station. Johnson was taken to the hospital, and eventually thousands appeared outside the precinct. For the record, the two officers were not indicted for their brutality.

Malcolm continued to be one of his organization’s most popular voices, preaching the need for separation from white America and for Blacks to eventually return to Africa but only after establishing an independent nation for African Americans in North America. He also believed in Black superiority and the fall of white culture was imminent during the early ‘60s, and likewise was skeptical of the mainstream Civil Rights movement and Dr. King, describing the 1964 March on Washington as “the farce on Washington.” His opinions began changing after he broke with the Nation of Islam in ’64 and made a personal pilgrimage to Mecca. He was assassinated on Feb. 21, 1965 by members of the Nation of Islam. For more, I highly recommend watching Spike’s Malcolm X (1992).

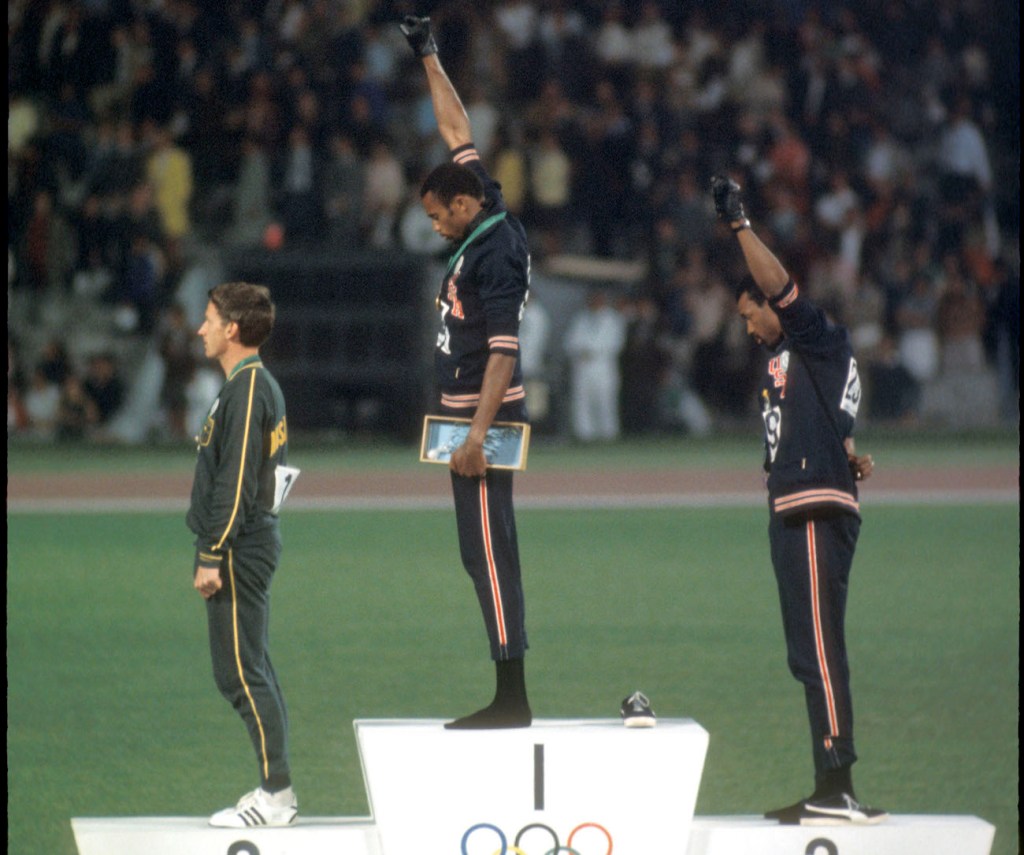

Tommie Smith, John Carlos, and the Black Power Salute

As we hear Malcolm X’s words, Da 5 Bloods next shows an image of Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ iconic Black Power salutes during the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City. Those games were actually held in October of that year, ironically coinciding with the Mexican government’s bloody crackdown on student protests occurring earlier that month (something we get a glimpse of in the movie Roma). Smith and Carlos won the gold medal and bronze medal, respectively, in the 200-meter dash. During the playing of the U.S. national anthem, both American men on the podium raised a single black-gloved hand in what is commonly seen as the image of Black Power, which in ‘68 was considered subversive by many white Americans.

Both Smith and Carlos were members of the Olympic Project for Human Rights, as was Australian silver medalist Peter Norman, hence each having the same logo on their jackets. Smith even later said in his autobiography the salute was for “human rights” instead of “Black Power.” All three—including Norman who suggested the Black Americans wear a single black glove—were ostracized by their home countries as a result. Time magazine, for one, suggested Smith and Carlos perverted the Olympic ideal of “Faster, Higher, Stronger” to “angrier, nastier, uglier.” Both men’s families received death threats, although Smith was able to still pursue a career in the NFL. In Australia, Norman was denied the right to compete in the 1972 Olympics despite qualifying and was suspiciously absent from the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney.

Kwame Ture

Images of inner-city slums that have clearly been abandoned by the White Flight to the suburbs of the mid-20th century are punctuated by a brief interlude of Kwame Ture saying, “America has declared war on Black people” in April 1968. Ture was one of the most significant members of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements during the ‘60s, and someone FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover infamously abhorred. Hoover believed Ture would replace the murdered Malcolm X as a “black messiah.”

Ture was born in Trinidad before immigrating to the U.S., and more specifically New York City, at the age of 11. He attended Howard University and became an outspoken public speaker, developing the Black Power movement out of his leadership of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. During the early ‘60s, he was a proponent of peaceful protest and the Civil Rights movement, including when he acted as one of the original freedom riders in 1961, riding desegregated interstate buses into the Jim Crow South. By ’64, however, he became increasingly disillusioned with Martin Luther King Jr.’s approach, which led to him calling for “Black Power” in 1966. This in turn led to him becoming one of the earliest members and leaders of the Black Panther Party, which was further to the left and more aggressive than the mainstream Civil Rights movement, calling for safety and self-sufficiency in Black communities, as well as an embrace of socialism and Pan-African ideals.

Targeted by the FBI and its COINTELPRO program, Ture was driven to move to Africa in Ghana and then Guinea in 1969. This is when he adopted the name Kwame Ture and eventually used it while touring the U.S. again in the 1970s, although law enforcement still derisively referred to him by his birth name of Stokely Carmichael. Lee explored this further in BlacKkKlansman (2018) where Corey Hawkins played Ture, but local law enforcement insisted on calling him Carmichael while spying in fear of him driving the local Black community of Colorado Springs to violence.

Operation Ranch Hand (Agent Orange)

The first specific historical event in Vietnam that Da 5 Bloods references is the U.S. military’s infamous Operation Ranch Hand. The substance we call Agent Orange actually comes from the British military, who pioneered the use of the deadly chemical weapon during their colonial conflicts in Malaysia between the late ‘40s and 1960 (aka the “Malaysian Emergency”). Agent Orange is a deadly mixture of two herbicides, 2, 4, 5-T and 2, 4-D. The chemical was designed to kill crops and forests (hence “Ranch Handers” in the military joking, “Only you can prevent a forest”). The intent was to starve rural South Vietnam and thereby starve the Viet Cong forces. Of course it was also starving civilians. Parts of Cambodia and Laos were also illegally doused.

It’s estimated around 20 percent of South Vietnam forests were sprayed at least once—with 10 percent of trees dying after one spray. It’s estimated that up to four million Vietnamese were exposed to Agent Orange with the Vietnamese government estimating lifelong health problems for three million residents; the Red Cross estimates one million Vietnamese were permanently disabled by the chemical warfare. The U.S. government denies the numbers are that large but a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study found that American servicemen who handled Agent Orange were more likely to develop leukemia, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, heart disease, and various forms of cancer. There was also increase in the rate of birth defects among the children of service members who handled the substance.

Angela Davis

During the poisoning of Vietnamese forests, we also see activist Angela Davis speaking in Oakland in November 1969. She said, “If the link-up is not made between what’s happening in Vietnam and what’s happening here, we may very well face a period of full-blown fascism very soon.” Spike likely picked this specific quote given the current state of affairs in the U.S. with a president who is constantly undermining American institutions, but it’s also highly applicable to the days of Richard Nixon (and illegal bombing in Cambodia) too.

Davis is a legend in the American left and trailblazer on issues of class, feminism, and dealing with the American prison system. She also is a self-described Marxist and former member of the Communist Party and affiliate of the Black Panther Party. She joined both while organizing protests against the Vietnam War in the late ‘60s, which led to her being fired (twice) by UCLA, where she was an assistant professor of philosophy. She also came into controversy when guns registered to her name were used in the armed takeover of the Marin County Civics Center in San Rafael, California. The domestic terrorist attack was orchestrated by teenager Jonathan P. Jackson, who kidnapped Superior Court Judge Harold Haley in order to coerce the release of the Soledad Brothers. The resulting firefight left Jackson and Haley dead, as well as two others. Davis was acquitted on any association with the crime.

Davis became a major voice in second wave feminism in the 1970s and is now one of the national leading voices in the calls for abolishing the prison-industrial complex. She has been inducted in the National Woman’s Hall of Fame and is a professor emerita at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

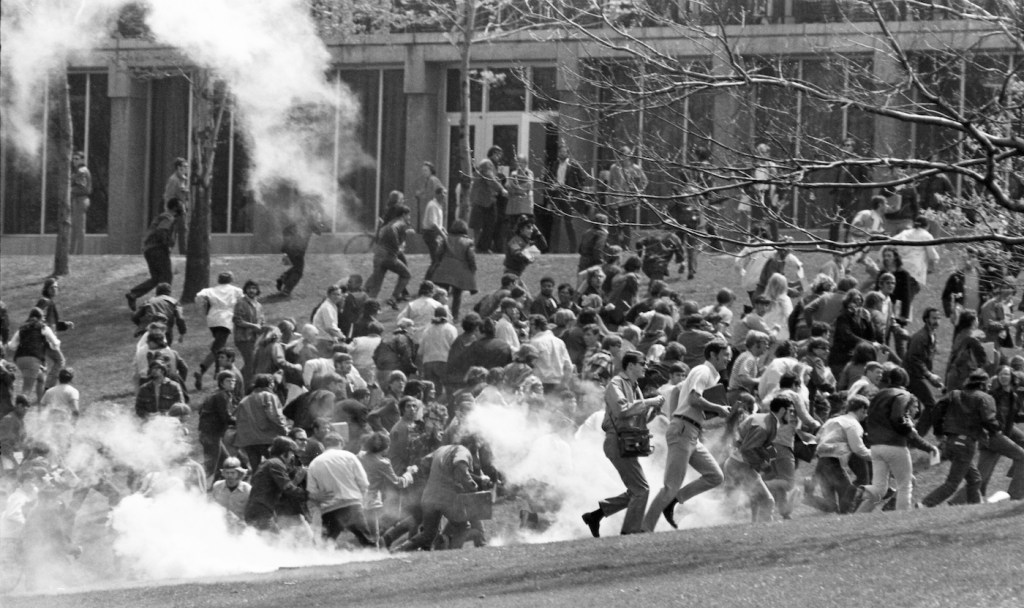

Kent State University Shootings

Da 5 Bloods next includes the infamous shooting at Kent State University, which resulted in the deaths of William Schroeder, Allison Krause, Jeffrey Miller, and Sandra Lee Scheuer. None of them were older than 20. The shootings occurred on May 4, 1970 when 13 unarmed Kent State students were shot while protesting (or observing the protest) of the Vietnam War. They were fired upon by the Ohio National Guard, who came to “control” the protest that featured about 300 protestors and hundreds of more observers. Scheuer and Schroeder were among the observers. The Guard had ordered the protestors to disperse, when the students refused they fired tear gas canisters at the students. When the students still stayed in place and threw rocks and canisters back at the soldiers, the National Guard fired 67 rounds of bullets over 13 seconds, killing four students and injuring nine others, one of whom suffered permanent paralysis.

There was immediate nationwide outcry over the images of dead teenagers on the nightly news and morning newspapers, as well as protests across college campuses across the country. More than 450 colleges closed in fear of violent and nonviolent protests. President Nixon and his administration were as callous as expected, with White House press secretary Ron Ziegler smugly saying, “When dissent turns to violence, it invites tragedy.”

Jackson State Killings

Less than two weeks after Kent State, college students were once again shot in the streets, this time leaving two young Black men dead, Phillip Lafayette Gibbs and James Earl Green. Their deaths occurred after Mississippi State Police opened fire on around 100 students from Jackson State College (later renamed Jackson State University). The students had gathered to protest what turned out to be a false rumor about the assassination of African American Mayor Charles Evers. The students were reportedly pelting cars and motorists with rocks as they drove through the campus’ main road. Local law enforcement responded by sending in 75 police cars from both Jackson and Mississippi Highway Patrol.

While firefighters tried to put out a nearby fire, the police attempted to disperse the crowd of students near Alexander Hall, a woman’s dormitory by… opening fire on the dorm and the students in front of it. At 12:05am, two students died and another 12 were injured while cops fired more than 460 bullets over 30 seconds. Officers claimed they saw a sniper—a claim students denied and the investigating FBI found no evidence of. The President’s Commission of Campus Unrest concluded that there was obviously no justification for a “28-second fusillade from police officers” and called the slaughter of two students an “unjustified overreaction.” Still, there were no arrests or indictments of the trigger-happy officers.

Thích Quảng Đức

Thích Quảng Đức is the name of the Vietnamese Mahayana Buddhist monk who committed suicide by burning himself alive at a busy intersection in Saigon on June 11, 1963. He did this as a protest of Ngô Đình Diệm, who was then the President of Vietnam. Quảng Đức was protesting what he saw as the persecution of Buddhists under the Diệm regime. His self-immolation was captured in a photograph by Malcolm Browne, winning him the Pulitzer Prize. It also brought international outrage against the Diệm government, with American President Kennedy eulogizing Quảng Đức.

As protests at home and international pressure abroad rose, Special Forces loyal to Diệm’s brother began cracking down on Buddhist pagodas, and in the raids seized Quảng Đức’s heart which was being kept as a holy relic in a glass chalice after it did not burn in his body. Following this theft, more Buddhist monks began lighting themselves on fire. I believe, but cannot confirm, the next burning monk Da 5 Bloods shows from Oct. 27, 1963 is Ho Đình Văn.

Shortly afterward, Diệm was assassinated in a military coup on Nov. 2, 1963. The coup was discreetly supported by the U.S.

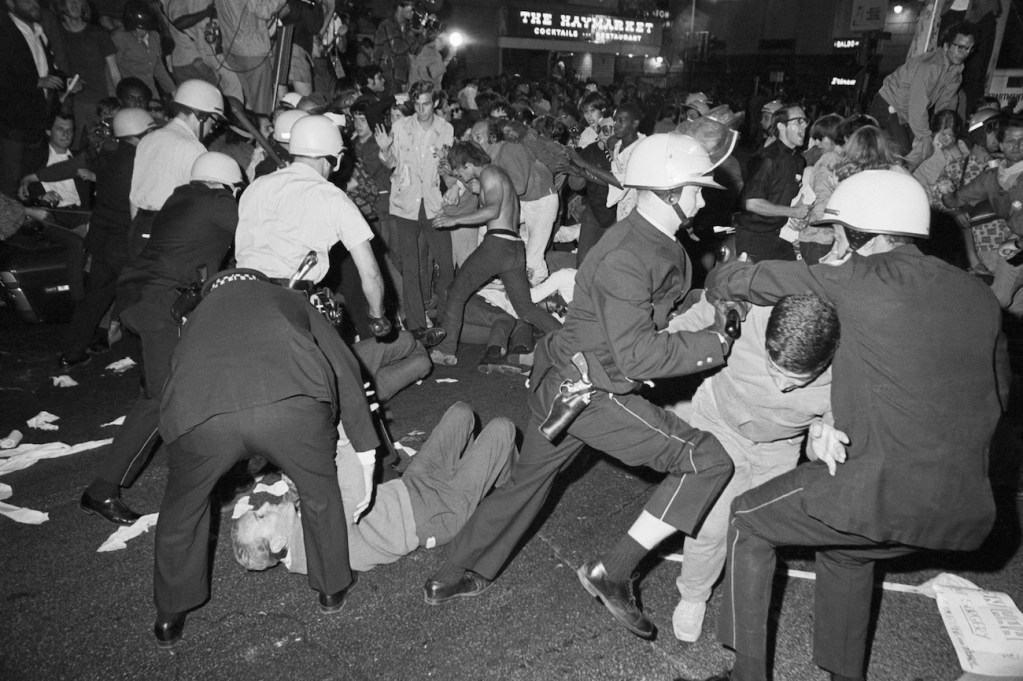

Democratic National Convention of 1968 and Police Riot

Some of the most infamous images of police brutality against protestors comes from the Democratic National Convention held in Chicago in ’68. Four years after the Gulf of Tonkin, the party of President Johnson was also firmly pegged as the party of the Vietnam War, particularly after Robert Kennedy’s assassination. Instead of a Kennedy, voters were getting LBJ’s vice president, Hubert Humphrey, on top of the ticket, and the party was running on a defense of sending young men to die in Southeast Asia.

This led to a coalition of liberal anti-war activists gathering in Chicago, including the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, the Youth International Party (Yippies), the Students for a Democratic Society, and more. Chicago Mayor Richard Daley thought he could dissuade them from organizing by refusing to grant protest permits during the convention, as well as by calling in 12,000 police officers and 5,000 Illinois National Guardsmen. He was wrong.

On Aug. 28, 1968, 10,000 protestors descended on Grant Park, with one protestor eventually tearing down the American flag that was raised there. The police responded by beating the young man, which caused protestors to hurl food, rocks, and allegedly chunks of concrete at the cops. The police responded by firing tear gas into the crowds. However, even as the crowd was dispersing into the streets, the cops continued firing tear gas at them, lashing out at other protestors marching toward the convention center, and chasing random individuals down in the streets, indiscriminately beating people with clubs, rifles, and mace. They attacked demonstrators, but also journalists, observers, and random bystanders. The use of tear gas eventually became so great, Humphrey could smell it while taking a shower at the Conrad Hilton Hotel.

Eventually protestors reached the hotel and convention where the stationed Illinois National Guard fired tear gas on protestors from one side as the police continued physically beating demonstrators (and almost anyone else) from the other end. This was captured on live television, shaking the country. There were 600 arrests, hundreds sent to the hospital, and ultimately a federal investigation concluding this was a “police riot.” Still, the national opinion soured on anti-war protestors afterward. Humphrey lost to Nixon.

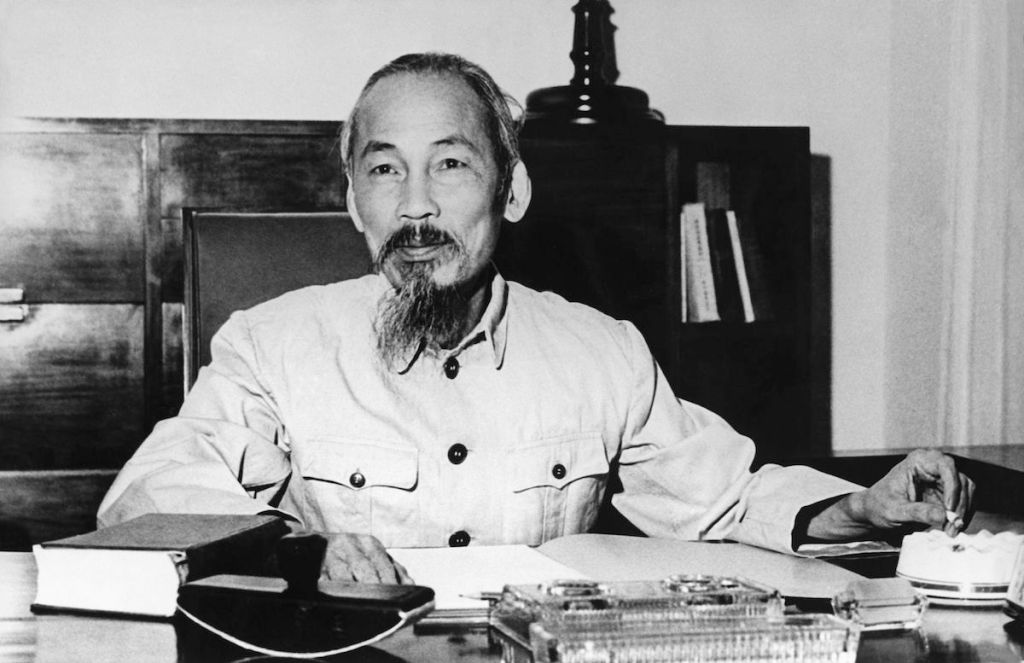

Hồ Chí Minh

Da 5 Bloods shows crucial revolutionary and political leader Hồ Chí Minh playing with children in 1955. While it’s a peaceful image, Hồ was a key figure in both the First Indochina War and Vietnam War to come. An ideological Marxist-Leninist, Hồ believed in separation from colonialist powers and an embrace of communist rule, leading the Việt Minh independence movement that began in 1941, which led to the formation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) in ‘45. You can imagine the U.S. and CIA weren’t exactly thrilled about that. Hồ served as Prime Minister of North Vietnam from 1945 to ’55 and as president from ’45 until his death in 1969.

Along the way, he led revolutionaries against the French Union’s French Far East Expeditionary Corps, defeating that colonialist power in the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954 and thereby ending the First Indochina War. It was around his flag the Viet Cong rallied during the Vietnam War to unify the country, which the U.S. tragically interfered in. Although Hồ did not live to see the end of that war, dying of heart failure in September 1969. Nonetheless, when the Viet Cong finally took Saigon, they renamed the city after him.

Hey, Hey, LBJ

We’ve talked around LBJ’s contributions to the Vietnam War, but we see the American president being mocked in the next Da 5 Bloods archival footage by a protest sign labeling him a war criminal. The pretext of the Gulf of Tonkin is indeed shady and it led to LBJ squandering what was otherwise a strong domestic legacy that included signing the Civil Rights Act, Voting Rights Act, and the creation of Medicare and Medicaid. He also escalated a war that led to more than 58,000 Americans dying in the jungle, and military operations that killed as many as two million civilians between Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. Hence the protest chant, “Hey, hey LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” It was wise (but far too late) when he announced he wouldn’t run for reelection on March 31, 1968.

Still, if you wanted to see a war criminal, just wait until who came next.

Nguyễn Văn Lém’s Execution

Spike next shows the infamous summary execution of Viet Cong officer Nguyễn Văn Lém at the hands of South Vietnamese Brigadier General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan. The war crime occurred on Feb. 1 1968 when Lém was captured during North Vietnam’s Tet Offensive against South Vietnam and American forces. Lém was brought to Loan in Saigon, who summarily executed Lém with his sidearm revolver. It’s later been reported that Lém himself committed a war crime when he executed with a knife Lt. Col. Nguyen Tuan, his wife, their six children, and Tuan’s 80-year-old mother. However, Loan did not know any of this. Rather he is reported to say after pulling the trigger, “If you hesitate, if you didn’t do your duty, the men won’t follow you.”

The murder was witnessed in real-time by NBC cameraman Võ Sửu and AP photographer Eddie Adams. It instantly became a famous image that led to international disgust for the Vietnam War. Adams later said, “Two people died in that photograph. The general killed the Viet Cong; I killed the general with my camera.” After the fall of Saigon, Loan immigrated to the U.S. INS tried to deport him for committing a war crime, but Loan was pardoned by President Jimmy Carter.

Bombing of “Napalm Girl”

The most haunting image of the montage, and one that imprints into your mind of anyone who sees it, is that of a naked little girl screaming in agony after being burned by napalm. The image comes from the village of Trảng Bàng in South Vietnam circa 1972.

On June 8 of that year, South Vietnamese planes dropped American napalm on the village because it had been recently attacked and occupied by Viet Cong forces. One South Vietnamese pilot, however, mistook civilians fleeing the local Caodi Temple to be Viet Cong and dropped the incendiary petrochemical on the civilians. Among them was nine-year-old Phan Thi Kim Phúc. Kim Phúc’s clothes were completely burned off by the fire, with the napalm searing her back in third degree burns. She was luckier than two cousins and two other villagers who were incinerated by the flames.

The photo became one of the most indelible images of the Vietnam War, and it won AP photographer Nick Ut a Pulitzer. Immediately after taking the photo, Ut carried Kim Phúc and other injured children to the Barsky Hospital in Saigon where doctors initially thought Kim Phúc would die. She would begin a 14-month hospital stay that included 17 surgeries, including skin transplants. It wasn’t until visiting a special clinic in West Germany in 1982 that Kim Phúc was able to regain full body movement. She eventually immigrated to Canada.

Upon seeing that image in ’72, President Nixon privately suggested the photo might have been staged to undermine his war policies. If only he knew you just need to repeatedly shout “fake news.”

The Resignation of Richard Nixon

President Nixon resigned from the Oval Office on Aug. 9, 1974. He did so only after the Republican Party of his day proved they still had dignity enough to honor the Constitution and urged Nixon to resign following the release of the “Smoking Gun Tape,” which was a recording that proved he acted to thwart the investigations into the White House burglaries after knowing his White House had been behind the burglaries into Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate Hotel during the 1972 presidential election. This was in direct contradiction of Nixon’s protestations (and lies) of innocence for more than a year. Republicans guaranteed he’d be impeached in the House and probably removed by the Senate.

Nixon resigned in disgrace after denying the stories in The Washington Post, attempting to hide the incriminating tapes he recorded of himself—vainly thinking they’d be used in posterity to document his greatness (or paranoia)—from Congressional oversight, and committing the “Saturday Night Massacre” where he fired two attorney generals in a night until he found a third one who agreed to fire the U.S. special prosecutor investigating the Watergate break-in. Most of all, this came after a plurality of the American voting public turned on him upon the majority belatedly agreeing in polls he was a liar.

None of it had to do with the illegal bombings Nixon escalated in Cambodia. In fact, Nixon’s collaborator in Secretary of State Henry Kissinger won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1973 for signing a ceasefire with Lê Đức Thọ.

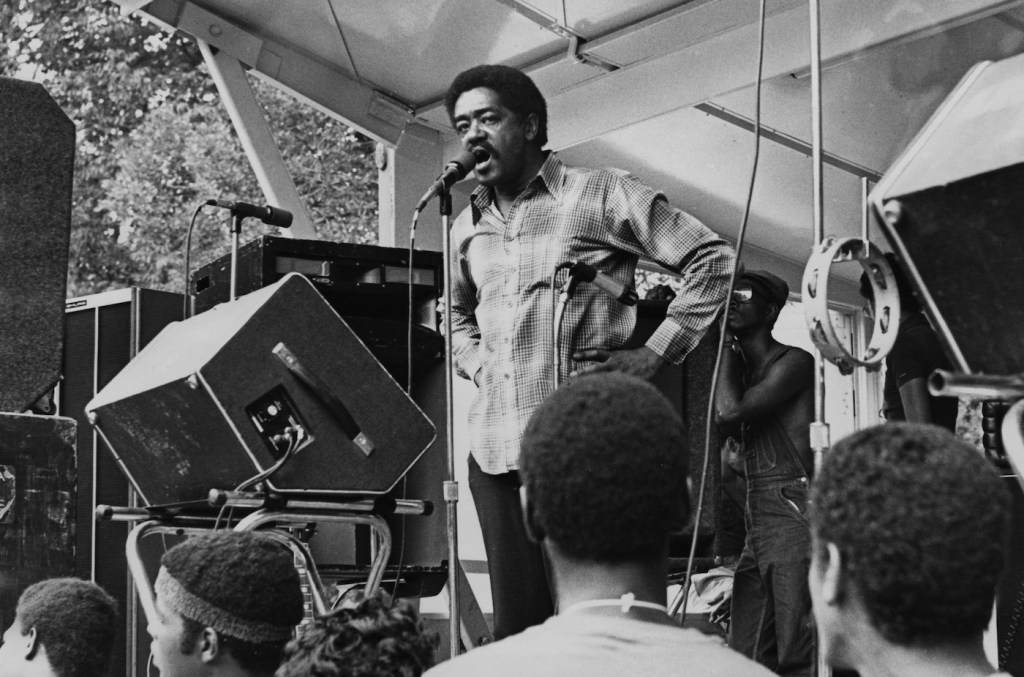

Bobby Seale

Bobby Seale, co-founder of the Black Panthers Party and one of the “Chicago Eight” indicted with felonies following the Chicago riots during the 1968 DNC convention, makes a late appearance in the Da 5 Bloods montage. Seale co-founded the Black Panthers Party in 1966 with Huey P. Newton in Oakland. The pair were inspired by Malcolm X and became politically active after his assassination in ’65. The Black Panthers’ original slogan was “freedom by any means necessary.” It was a quote from Malcolm.

In the film, Seale is included to illustrate Da 5 Bloods’ larger theme about the cyclical nature of Black men being sent off to war by the U.S. government. “In the Civil War, 186,000 Black men fought in the military service, and we were promised freedom and we didn’t get it. In World War II, 850,000 Black men fought and we were promised freedom, and we didn’t get it. And now here we go with the damn Vietnam War, and we still ain’t get nothing but racist police brutality, et cetera.” Sound familiar?

Fall of Saigon

The capital of South Vietnam fell to the People’s Army of Vietnam (North Vietnam) and the Viet Cong on April 30, 1975. The North Vietnamese began their attack on the city the day before, which led to the last remnants of U.S. Armed Forces, journalists, and essentially all other Americans to flee via evacuating helicopters that were lifting off of literal hotels.

Spike also includes some of the starkest images of America’s failure during this time, including when the U.S. military was ordered to push their own helicopters off American warships. This is because the ships were so overwhelmed with Americans who fled Saigon on April 29 that to keep the ships from overcrowding, Operation Frequent Wind ended with the military tossing their own choppers into the sea. It was an ignominious end to the American vantage of the war.

It was still better than the fate suffered by “boat people” as shown in the movie. These were the refugees who fled Vietnam by the hundreds of thousands. Most of which did not leave until well after the end of the war in ’75. The humanitarian crisis began in earnest three years later in 1978 when scores of folks fearing for their lives under a unified Vietnam attempted to flee to Malaysia, Hong Kong, Indonesia, or anywhere else. In ’78, one vessel infamously abandoned 1,200 passengers on an uninhabited island.