Barbie, Transformers, and Hollywood’s Rocky History of Toy Brand Movies

Toy lines are having a big summer between new Transformers and Barbie films, but it wasn't always so. We explore the evolution of toys-turned-film.

Hollywood is always looking for the next big source of entertainment. Right now, it seems that video game adaptations are finally on the verge of legitimacy due to the success of The Super Mario Bros. Movie and HBO’s The Last of Us. Before that, it was superhero movies. And on and on it goes. However, the industry’s endless search for intellectual property (IP) has for decades led to false starts and brief flirtations with the world of toys and board games. When looking across the chronology of those attempts, a few key flaws stand out as to why the concept has still yet to catch on quite as strongly as comic books or video games.

Adaptations of products are notoriously difficult to get right, because they are not necessarily attached to a narrative that people know. The basic premise of a toy’s brand might be established, but who those characters are and what that world looks like has yet to be filled in. By design, key narrative elements to build a story around are left vague, and to the child’s imagination to fill in.

Yet with the upcoming release of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, not to mention the seventh Transformers movie, here’s an opportunity for the medium to evolve. But what can Mattel learn about toy and game adaptations from the past before they take their fashion icon to the big screen? To know that, we have to start at the beginning.

Clue (1985)

Before many modern toy-based adaptations came this board game cult hit from the 1980s. Based on the murder mystery experience that had been dubbed Cluedo internationally, director Jonathan Lynn’s Clue worked on a miniscule budget of $15 million. But with barely any storyline besides a mysterious homicide and a few notable character names, it seemed impossible for the filmmakers to create a compelling adaptation that would both amuse audiences and inspire product sales.

Perhaps it’s Clue’s lack of corporate focus that paid off, at least creatively. The movie never felt as if it was trying to sell anything and instead used the board game as a blueprint for a satire of whodunit mysteries. Its hilarious cast and reframing as a dark comedy ensured that the outside-the-box approach paid off. This wasn’t a paint-by-numbers exercise but instead a genuine creative endeavour that took risks and worked within its own boundaries.

Fast-paced and witty dialogue from writers Lynn and John Landis brought the scenes to life and gave personalities to characters that players previously had to make up. It was the correct balance of taking advantage of those gray areas and paying homage to the elements that board game enthusiasts enjoyed. Clue ultimately worked because it knew what it wanted to be from the start.

Masters of the Universe (1987)

Although toys had inspired big screen spectacles before the release of Masters of the Universe, this live-action outing from director Gary Goddard is definitely an early standout of the action figure age. He-Man and the Masters of the Universe had already begun as an animated series in 1982, inspired by the Mattel toys. Although looking back on the show now, it may seem dated, the series did help to establish plenty of fun and wacky characters that kids just had to own. It was a roaring success and plenty of fans are still nostalgic about that initial run. It stood to reason that it would garner a big screen recreation, but arguably the era it was made in let it down.

Masters of the Universe was simply too ambitious of a project to really work without the technology and filmmaking techniques of the 1980s. Although it could be argued that classics like Star Wars (1977) had already been created, the narrative behind the He-Man franchise simply wasn’t strong enough to survive the limited execution afforded such properties in the ‘80s (especially by the Cannon Group).

The charismatic Dolph Lundgren taking on the lead role of He-Man didn’t hurt the movie’s chances. But the script barely resembled the animated show due to those budgetary and technological concerns. Additionally, the narrative depth of the animated series wasn’t complex enough to actually sustain being drawn out to a feature-length production, which only exacerbated issues further. The solution Cannon came up with—setting the majority of the movie in suburbia with He-Man being a fish out of water—didn’t help matters. The lesson here is therefore twofold. To have the capabilities to produce an ambitious adaptation and enough story to fill it.

Toy Story (1995)

The revolution in toy-based moviemaking, ironically enough, came from an original property. Toy Story was of course an original concept from the then fledgling Pixar Animation Studios (it was their first feature film). Yet it also was packed to the brim with actual toy brands that interacted with original characters. By extension, those characters were based on archetypes from the toymaking industry, but director John Lasseter and the rest of the Pixar team took the opportunity to distance themselves from any one individual product line.

The movie was of course a massive hit and defined the computer-animation moving forward, and it taught other toy-inspired adaptations an important lesson. Despite the lead characters being inanimate objects, they were still displaying very human emotions. And that includes the ones who were based on real products: Hasbro’s Mr. Potato Head, plastic Army Men, and even Mattel’s Barbie.

Compared to Clue and Masters of the Universe, the movie wasn’t trying to turn toys into real people. Instead it made the toys themselves feel real because of their conflicts and relationships. That made Toy Story far more relatable and emotionally moving. Toy Story 2 (1999), Toy Story 3 (2010), and Toy Story 4 (2019) all built on that same quality. The toys had to worry about things that the audience would have never experienced: Getting sent to a museum, losing their owner to college or getting replaced by a new toy. But the core principles of those feelings were instantly recognizable.

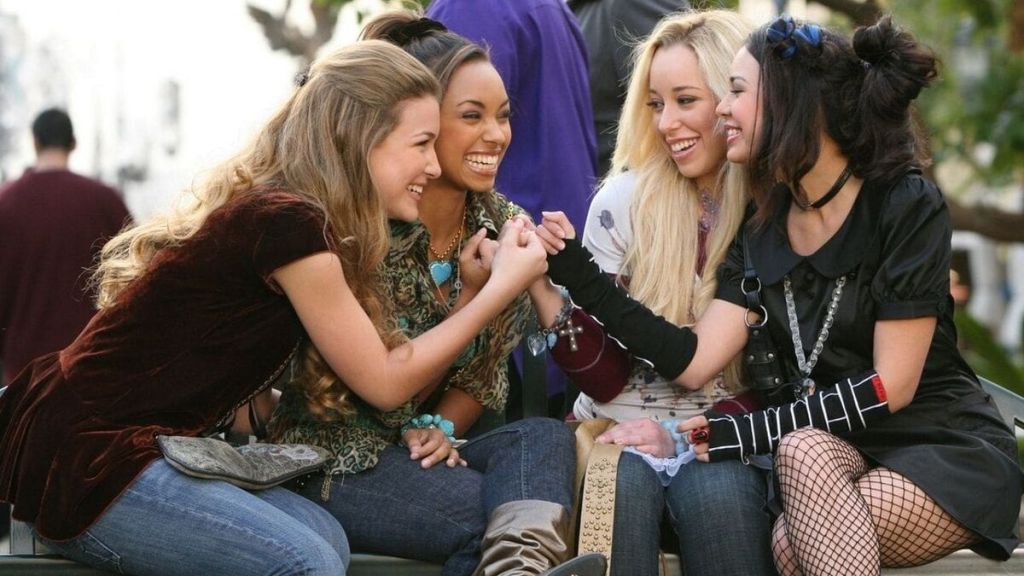

Bratz (2007)

Bratz is another example of everything that could go wrong with a toy adaptation. Although the characters had personalities that were relatively defined through the products, mainstream audiences simply didn’t know who each individual ‘Brat’ was. The film, which was directed by Sean McNamara, very much took a Mean Girls or Legally Blonde style of approach. In making those decisions the film couldn’t decide who its audience was. In its premise, perhaps teen girls would have been the right demographic. But Bratz as a brand appealed to a slightly younger market.

Artistically, Bratz cannot be compared to the risks that Clue took or the emotional depth that Toy Story produced. Just like Masters of the Universe, this was a concept that was stretched to its limits. With even less story to draw from, a plot revolving around a war against the school principal left the intellectual property floundering. In the years since, Bratz has been far more successful in the short-form animated world, with a younger audience as its key demographic. That’s where this brand thrives. Perhaps the film’s biggest crime is that it’s generic. It could have been based on literally anything. Successes in the toy industry certainly aren’t based on the notion of being average and plain.

Transformers (2007)

It’s fair to say that the evolution of the Transformers movies could warrant an article unto themselves. With Rise of the Beasts now in theaters, it’s no surprise that the Transformers franchise has hugely influenced modern toy-based adaptations. From a financial perspective, the series has produced some of the biggest successes. Michael Bay’s first attempt at the franchise proved to be imaginative, huge in its scope and scale, and appealing to mainstream audiences. It was a good introduction to the world, and while it might not have been everyone’s cup of tea, it at least took the series in a new direction—specifically for teenagers with its premise switching to a boy buying a (transformer) car to impress a girl.

To Transformers’ benefit, there was a huge wealth of material to inspire future stories, thanks to the comics and animated shows. This didn’t just feel like the elongation of a concept inspired by some plastic. It was instead the growth of a fictional universe, putting a fresh coat of paint on some much-loved narrative beats and characters.

But in the Transformers sequels, any heart was cut out of the juggernaut. From a quality perspective, there were diminishing returns. Nothing could capture the magic of seeing these robotic warriors in a real sequence for the first time. Although the battles got bigger and the lore-based cuts got deeper, audiences began to move away from the series. Hardcore fans certainly weren’t being catered to, but by the time Transformers: The Last Knight struck in 2017, it was obvious something had to change.

Bumblebee (2018) was supposed to be the cure to the plague of apathy. It wasn’t as concerned with huge explosions and ridiculous humor. It instead told a personal story of a girl and her car… that just so happened to be an alien robot. It respected the source material but brought in its own artistic flair. Director Travis Knight had a clear vision and lead Hailee Steinfeld was the perfect, grounded foil to the over-the-top world she was about to step into. Bumblebee is a showcase of learning from the chronology of toy-based moviemaking and going back to basics with a human narrative that also includes a toy. Alas, it also wasn’t a hit, hence the back-to-basics pivot in Rise of the Beasts.

G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra (2009)

G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra and Snake Eyes from 2021, were essentially born from the Transformers methodology. Hit the audience with a lot of noise and action, forget the need for any true character growth, and throw in a few fun references to old lore. It’s a strategy that woefully failed, still angering diehard fans while never fully finding its mainstream crowd. Although G.I. Joe: Retaliation (2013) attempted to course correct with a slightly closer adaptation to the toys, comics and animated shows, it just wasn’t enough. At least a cast overhaul and directorial change from Stephen Sommers to Jon M. Chu didn’t remove the sour taste that the 2009 entry left in the mouth.

Still, G.I. Joe adaptations have continued to lack heart. Every iteration has been displayed as the start of a new shared universe; a concept that jaded moviegoers roll their eyes at, considering the franchise just simply hasn’t earned it. There are years of compelling stories to tell, but with the live-action versions largely hellbent on ignoring the best ones, it’s difficult to see how the toy adaptation is ever going to take off.

Battleship (2012)

The less said about Battleship the better. Directed by Peter Berg, the game-based adaptation is from the same school of thought as G.I. Joe and Transformers. In fact, there were rumors of a larger shared universe being developed that would try to cross these Hasbro properties over. The cynical development style, which put toy selling and blockbuster-building above story, can be traced to Battleship’s inevitable downfall. Perhaps part of the problem was that there was no narrative for Battleship to begin with. It turns a naval war game inspired by the Second World War into a lazy, run-of-the-mill alien invasion flick in the post-Independence Day mold.

The idea that aliens could be thrown into the mix just to make the movie seem more cinematic, or at least indistinguishable from other 2000s blockbusters, was ridiculous. With no true direction and nothing to say, the only reason behind this adaptation was financial. Upon its initial announcement fans had a sinking feeling, and they were right.

The Lego Movie (2014)

The Lego Movie was the perfect encapsulation of every lesson that had been learned through years of trial and error in this genre. The movie relied upon the Lego product to create humor and spark narrative. But it was inventive and original. It blended live-action and animation together, to allow the toys to feel authentic. They’re literally toys. It also took the idea of play and turned it on its head, somehow churning out intelligent thematic commentary on control, facism, and group-think. Directors Phil Lord and Chris Miller ensured that The Lego Movie appealed to its target demographic of kids with its vibrant visuals and whimsical humor. But its adult storytelling ensured that all ages could enjoy it too.

Although The Lego Movie 2 (2019) might have been a slight step down from its predecessor, it nonetheless delivered on many of those same beats. But it was The Lego Batman Movie in 2017 from director Chris McKay that shocked audiences the most. Its meta humor could only be achieved thanks to the Lego product, and it completely broke down Batman as a character and all the tropes of his cinematic outings. This was a case of a toy actually elevating another IP and allowing a story to be told that simply wouldn’t work in any other format. The Lego Batman Movie and the original brick-based release are both strong indications of the potential of toy adaptations, and how their narratives can be used to say something unique.

Trolls (2016)

DreamWorks Animation’s Trolls franchise might just be the anomaly. From a quality perspective, the two films in the series thus far are lacking. And yet, the box office and family appeal has outshone many other toy-based adaptations. Trolls, which was directed by Mike Mitchell and Trolls World Tour from Walt Dohrn, found a formula and stuck to it.

They feature over-the-top animation, a vibrant color palette, silly humor, and bizarre character archetypes. Somehow, these elements came together to convey the essence of what the Trolls toys are for kids. The franchise found its audience and stuck to it. Trolls and its sequel certainly didn’t attempt to convey a larger thematic message, nor did the two films lose sight of the product that got them commissioned. The duo break all the rules and come out better for it. But when the lead characters are fantastical creatures that hug, and dance and sing all day long, there really isn’t any other direction to go in. Trolls Band Together shows no signs of departing from that ideology and will continue to showcase the wackiness of the toy brand regardless of what critics think.

Barbie (2023)

The upcoming release of Barbie appears to be taking away the most important message from the successes and failures of past adaptations. It’s letting the toys be toys while allowing the plastic figure to interact with the real world. It seems to have found its audience, aiming at older viewers who remember having Barbies in their younger years. It also seems to be saying something deeper, carrying a message about identity and breaking away from conformity. Its narrative might be inspired by the Barbie everyone knows, but it’s also obviously breaking off in its own direction.

For future toy and board game adaptations to work they need to carry the flavor and feel of the product and respect its lore while moving to a new narrative that actually has a purpose. It’s taken years of releases to finally get to a formula that works.